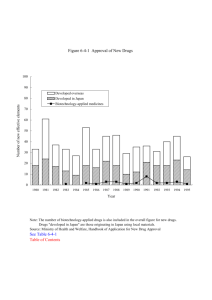

January 1989 WP 1904-89

advertisement