THE DUAL LADDER: WP1692-85 Thomas J. Allen

advertisement

THE DUAL LADDER:

MOTIVATIONAL SOLUTION OR MANAGERIAL DELUSION?

Thomas J. Allen

Ralph Katz

WP1692-85

August, 1985

The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of the U.S.

Army Office of Research, which supported the research which this

analysis is based, and the management and personnel of the nine

firms that collaborated in the research.

ABSTRACT

The "Dual Ladder" reward system has been used for years by

industry as an incentive system to motivate technical performance.

Its effectiveness has been called into question on many occasions,

The paper will report the results of a survey of nearly 1,500

engineers and scientists in nine U.S. organizations.

In this survey.

engineers were asked to indicate their career preferences in terms of

increasing managerial responsibility, technical ladder advancement or

more interesting technical work.

Responses indicate marked

age-dependent differences in response, particularly a strong increase

in the proportion preferring more interesting project work over

either form of advancement.

-I-

INTRODUCTION

The effectiveness of so-called "dual ladder" career systems has

long been debated in both industrial and academic circles (Moore and

Davies, 1977; Smith and Szabo, '1977; Sacco and Knopka, 1983).

The

idea was conceived somewhere in the dim past by a research manager or

personnel administrator, who hoped to increase the number of career

opportunities available to high performing technical professionals

and thereby to sustain their motivation.

The original idea held to the implicit assumption that

productive engineers and scientists were being "forced" into

administrative roles in order to attain higher salary levels and

organizational prestige.

to their organizations.

Their technical talents were thereby lost

The assumption that productive scientists

and engineers had to be "forced" into management was shown to be

invalid.

Many studies (Ritti, 1971; Krulee and Nadler, 1960; Bailyn.

1980) have shown that a very high proportion of scientists and

engineers in industry see their career goals in terms of eventual

progress in management.

In fact, a recent survey of MIT freshmen

shows fully 20 percent of those choosing engineering majors citing

management as their ultimate career goal.

-2-

Nevertheless, there remains some proportion of the technical

staff of most organizations who prefer to remain in full contact with

technical problem solving, for whom management has no attraction, and

who could potentially find a technical ladder career rewarding.

The

basic question is, just how large this proportion is.

Companies vary widely in their estimates.

Some restrict

technical ladder entry severely, while others promote a relatively

high proportion of their staff into technical ladder positions.

Companies also vary widely in their enthusiasm over the concept.

A

representative of one company, who requested anonymity, reported to

the authors that when his company was recently considering the

possibility of such a system. he informally polled the management of

13 other companies that already had such a system.

Most reported

varying degrees of satisfaction, but when asked if, given the chance,

they would do it over again, 12 of the 13 replied definitely not. 1

The problems underlying the dual ladder concept are several.

First there is a general cultural value which attaches high prestige

to managerial advancement.

society in general.

Managers are seen as important in our

Vice presidents are accorded high prestige.

Someone working for an industrial organization with the title of

Senior Research Fellow is not accorded the same degree of prestige by

1

Conversations which one of the authors has had recently with

managers of the thirteenth company question its status as an

exception.

-3society at large.

As a result, technical staff begin very early to

think about eventually attaining a management position.

Consequently

when told that they have been selected for promotion to a technical

ladder position,

such a person hears a very different message.

He

hears that the organization does not think that he will make a good

manager.

The technical ladder promotion then becomes a consolation

prize, and very often de-motivates an otherwise productive member of

the staff.

Second, despite many organizations' attempts to equate pay and

perquisites for the two ladders, there is one key ingredient of the

managerial ladder, which is missing from the technical ladder, viz.,

power.

As an individual progresses on the managerial ladder, the

number of employees reporting to that individual generally

increases.

When that manager requests action, those subordinates

generally mobilize to accomplish the action.

This is a strong

external indicator of power, hence also prestige.

As an individual

progresses on the technical ladder, neither the number of

subordinates nor visible power increase.

Hence a technical ladder

position is viewed inside the organization as less important than its

supposedly equivalent management counterpart.

Finally, organizations tend, over time, to diverge from the

initial design and intent of the system.

For the first few years,

the criteria for promotion to the technical ladder may well be

followed rigorously, but they gradually become corrupted.

The

technical ladder often becomes a reward for organizational loyalty

rather than technical contribution.

Equally damaging is the even

-4more prevalent tendency to use the technical ladder as a repository

for failing managers (Smith and Szabo, 1977).

Either of these

practices will destroy whatever reward value there may be in the dual

ladder system.

Given all of this, two key questions develop.

First of all,

what proportion if any of a laboratory's technical staff will find

the technical ladder career an attractive one?

Second, for those

others who will never be promoted to the limited number of managerial

positions, and who are not necessarily inclined toward the technical

ladder, what can be done to reward and continue to motivate them?

To address these questions, technical staff from nine

organizations were asked, along with a number of other questions, to

indicate their career preferences, whether toward management,

technical ladder, or whether they might simply be interested in

project assignments of a challenging and exciting nature irrespective

of promotion (Table I).

RESEARCH METHODS

The data presented in this paper were collected in a study of

engineers and scientists in nine major U.S. organizations.

The

selection of participating organizations could not be made random,

but they were chosen to represent several distinct sectors and

industries.

Two of the organizations are government laboratories,

one in the U.S. Department of Defense the other in the National

- -

TABLE

_

_

I

111_

Format of the Question

_

__

_

-----------------------·I--········

__

To what extent would you like your career to be:

a)

b)

c)

----

a progression up the technical

professionalladder to a

higher-level position?

a progression up the managerial

ladder to a higher-level

position?

the opportunity to engage in those

challenging and exciting research

activities and projects with which

you are most interested, irrespective

of promotion.

_------

--

1

.2

3

4

5

6

7

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

I

--

__

Aeronautics and Space Administration; three are not-for-profit firms

doing most of their business with government agencies.

remaining organizations are in private industry:

The four

two in aerospace,

one in the electronics industry and one in the food industry.

In each organization short meetings were scheduled with the

members of the technical staff to explain the general purposes of

the study, to solicit their voluntary cooperation and to distribute

questionnaires to each engineer individually.

In addition to the

usual demographic questions, the questionnaire included a number of

questions about the ways in which each individual viewed his future

career and the ways in which the organization structured its reward

system around career factors.

There are also a number of questions

addressing the way in which engineers view their jobs and the

-6importance that they attach to various features in their jobs.

Thecentral questions around which the present paper is developed are

those shown in Table I.

These questions ask engineers their

preference in terms of progression on either the managerial or

technical ladders or in lieu of these, the opportunity to engage in

challenging and exciting projects irrespective of promotion.

The

third question was included just for what was expected to be those

few engineers who might not be interested in the traditional paths

of organizational progress.

Individuals were asked to complete their questionnaires as

soon as possible.

Stamped, return envelopes were provided so that

completed forms could be mailed to the investigators directly.

These procedures not only ensure voluntary participation, but they

also enhance data quality since respondents must commit their own

time and effort.

The response rate across organizations were

extremely high ranging from 82% to a high of 96%.

A total of 2,157

usable questionnaires were returned.

RESULTS

Respondents varied in age from 21 to 65 with a mean of 43 and

standard deviation of 9.6 years.

Managers and those holding

technical ladder positions are included.

There are 545 managers and

521 engineers in technical ladder positions among the 2,157 who

completed the survey.

-7Respondents were initially classified as being oriented toward

a technical, managerial, or project-centered career if their response

on one of the three scales exceeded the response on the other two by

at least one scale point.

Those who reported equally favoring any

two of the three options were left out of the analysis.

A total of

1,495 respondents indicated a preference for one of the three

Of these, 488 (32.6%)

options.

preferred the managerial ladder over

the two alternative career paths, 323 (21.6%) preferred the technical

ladder and a surprising 684 (45.8%)

reported a preference for having

the, "opportunity to engage in those challenging and exciting

research activities and projects with which (they) are most

interested,

irrespective of promotion."

Such a large proportion of respondents preferring a somewhat

non-traditional form of reward arouses suspicions that the wording in

the question may have made the alternative more attractive than was

intended.

It would seem reasonable that, were this the case, the

induced preference would not be as strongly felt as preferences based

on the more substantial conviction.

Increasing the margin of

preference required in defining orientation does not, however,

decrease the proportion of those preferring interesting projects

(Table I).

I·

_

1

1·1111__·

-8-

TABLE II

I__

---·C---C---

___1___

--- -------

1____1__11___1_____1___·-··---------------------------

---·

I

-I

Sensitivity Analysis of the Scale Margin

Used in Defining Career Orientation

_····---I-·I----·)---·I

---I··1·-----·--I-·--------^··-----·

--

number of respondents preferring:

margin of

preference

(scale points)

managerial

ladder

technical

ladder

interesting

projects

I

458

(32.7%)

302

(21.5%)

642

'(45.8%)

2

290

(35.8%)

128

(15.8%)

393

(48.4%)

3

151

(36.5%)

50

(12.1%)

213

(51.,%)

In fact, the number of engineers reporting the project preference is

not as sensitive to the increased margin of specification as are the

numbers of preferring managerial or technical ladders.

It would

certainly appear from this that the project preference is relatively

strongly held and is unlikely to have resulted to any significant

degree to the wording of the question.

In addition, a more recent study (Epstein, in preparation),

using a less strongly worded third alternative, has produced nearly

identical results.

I-----

-9-

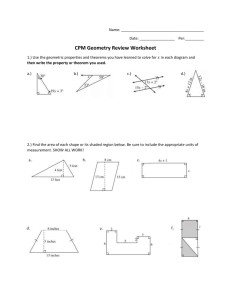

Orientation as a Function of Age

Career preferences, as one might expect, are significantly

related to age (F =

8.25; df = 2, 1,399; p < 0.001). The proportion

of engineers citing a preference for interesting projects increases

almost monotonically with age (Figure 1).

This may be due,

partially, to a realization that advancement opportunities along the

two traditional ladders is diminishing with age.

This can be only

partially true, since such a high proportion of those in their

twenties indicate this preference.

In fact, it is the most preferred

alternative for all engineers, save those from 25 to 30.

43 iC

Qfr.J

6 0

-

.-

PI sPORT

~~~~~~~~~:'-r'

T !- t-.!-,{{i

ch L- (>

*:; ~l, ':j-ci!tw i

J

N

EHti--GI EERS

40:EE

!2-. ' ~. .. ~~~~~~~~~~~

,~ - ~ ~

~~~~~~~~

N~~""·~e

~ ~~~/~~ ~ ~

t

....

i: ::_.

~

'%'.r.

...

.,....

P1).''ff'OC

:P

r_

1

'

·

--- '--r-

..

I-

.

I_

t--

0

LI

2, 5

iI

I

-

32 5

A GE

----

42 5

(

L

52 5

EA i )

FI GIRE 1.

CAREER PREFERENlCEE

OF ENGI HNEUit

NtiNE ORGANIZATIONS

S

FML-ICTION OF AGE (

i402)

!

E"

'l; ,I ilrI { ¢';t

17ItfO~IF~I

· i-~~~~~~~~~~~~

I [--..r!

I

-F

i

'f

-10The technical ladder career attracts the smallest proportion of

engineers in all ages.

The proportion indicating this preference

hovers around 20 percent showing only a mild peak among those in

their thirties.

The proportion preferring a managerial career peaks

in the late twenties and declines steadily thereafter.

Career Preference as a Function of Position

As one might expect. managers report a marked preference for a

managerial career.

There is some diminution with age (Figure 2) with

a concomitant increase in preference for interesting projects.

Only

for a brief period in their late thirties do managers show any

interest in the technical ladder.

Most of the engineers, who are on the technical ladder, prefer

one of the other two alternatives.

The younger ones tend to prefer

management over the technical ladder.

Older technical ladder

engineers indicate a preference for interesting projects.

i

iV,

'.,,

L:I

EiA

:%,

.,

'·

;··"I

·

a..t.: -.,r·sl:;

E

n

.i

. t. i

·i·

···· aF pil

::

rag-;

i-.

- h

::

,3

fi;F

vMH":Ek T

.,-.- P3~~J

"V

· -.-

'~'~

-'-

55

I iI!

,

,Ii',

- , f ,i_ E t

60

c

(I

L

iI.E,; t

a I't. -I

.-

374)

.1.

,/

'--

Jj

.3

.

.

?i .

~--~--.~.-

iltr

i

-T:TECHIN

-

~I~

l

..,

OF A-sGE

T

:

_- . :-

aI ' '::::..

~::-'---'

1 ·*'N E

·

::'

' i

]I

I

i

'i-

AGE

42.5

(YEAiR)

52'5

CA FEER PREFFREN CES OF TECHNI CAL

EtII iGTEERS AfS A FUIICT OrI

(N = 351)

1_1_

t

i

[

i

t~~~~

0

32. 5

" i:

%

·T

F GiiE

3.

IA !>)iER

C

.

i .·I·N

22, 5

:,.I ;

-F

A F((iii

-

.

, -i'm~..:.f

h- _

i:,:.X "T

(tYEA Fsit. )

CAREER PREFEiRENCEI

i

I

PRO-.0 POrT 1O

IA

5

,F

:;ii

RG=E

1__11__

li'Bil'i'iBT

I

POF(1 ORT I ONl

OF

(ICR,-'"

's . ; )

:L

"

"'fii

OF' AGE

Pi'OJE.CLt

iT O

i

N

A. F 1

;r

B t

-12Characteristics of Engineers as a Function of Orientation

Those engineers, citing different career preferences, differ in

a number of other interesting ways as well (Table III).

As expected.

those preferring the technical ladder are more concerned with their

professional reputation. while those preferring management are more

concerned with organizational matters.

They prefer more to work on

projects of importance to the organization and on those they see

having a potential for advancement.

The project oriented engineers are not so concerned with the

extemalities it appears.

They seein much more influenced by the

intrinsic nature of the task.

They prefer technically challenging

projects, having the freedom to be creative and original and working

with competent colleagues.

The three orientation seem to appeal to very different kinds of

people.

Of course, as if individuals shift their orientation over

time, as the data of Figure 1 suggest, then it is certainly possible

that all of these other preferences change as well in order to

preserve a logical system.

The present data being cross-sectional,

cannot determine whether there are actual changes in individual

orientation of engineers preferring management has increased in

recent years with a concomitant decrease in those who are interested

more in engineering work.

If there is a change over time, it would

seem to be a major reorientation of the individual's motivational

-13-

TABLE III

_IL__

II___

___I__

·I-----··-····--·--------II------

__

-----------

II------

__

_

·-----

----------

Importance of Job Characteristics

As a Function of Career Orientation

perceived importance of:

orientation

-------------------------------------managerial

technical

project

p

ladder

being able to pursue

own ideas

5.72

5.70

5.82

NS

building a professional

reputation

5.74

5.82

5.26

0.001

working with competent

colleagues

5.77

5.83

5.94

0.05

working on technically

challenging tasks

6.04

6.29

6.32

0.001

working on organizationally

important projects

5.36

4.74

4.70

0.001

working on projects

leading to advancement

5.94

5.06

4.09

0.001

working on professionally

important projects

4.92

5.11

4.81

0.01

having freedom to be

creative and original

5.78

5.99

6.07

0.001

-14-

base.

It is important to note that positioning of the questions in

the questionnaire.

Those dealing with motivational issues were

intentionally placed several pages ahead of the career orientation

questions.

So the responses to those questions were not prompted by

any thought on the part of the engineer as to career preferences.

Choosing two of the motivational variables, which show a

significant difference across orientations, we see a fairly stable

preference by orientation across different ages (Figures 4 and 5).

Young engineers with a project orientation value the freedom to be

creative and original at least as much as their older colleagues.

Similarly, those with a management orientation prefer to work on

organizationally important projects without regard to age.

Perception of the Reward System

Following the question about career orientation respondents

were asked to indicate the most likely form of reward for high

performance in their job.

They were given the same three

alternatives, management promotion, technical ladder advancement or

interesting project assignments.

A relatively high proportion of the younger engineers see the

technical ladder as the most likely reward.

For those over 30, this

diminishes considerably and interesting project assignments are

seento be the most likely form of reward (Figure 6).

Only about 20

to 25 percent of respondents see a management promotion as the most

likely reward.

This is less sensitive to age than either of the

-1 5-

J

'

'.

,,

-

r

t.-- ....

:i

-£ .*i' t .,

I

i

.. : ... "

:.iI

. .

-..

.

:

--.

*_

'

- t -!

.I

...v.: r'!:

t

S

v w-

!1 ,

/.. ?!:¢t-

...

e

.:

-

s

%

-

'

L w * _;

~~ ~

~

t

~

-. · ··I:·1.---~~~~~~~~~~7~

1L

, ! 'r

;

i

:~

~

~E ne3 s -,;;

_jjIf

.

r--J-'

:

_

_I,.

*,riri---·

:

i,

· i

!

r- :};

e

!._...

_...._._ ..

__! . .-..-..- t.....

.

Ir2

.

.,_.

_ _........ _ .1 _

5

J.YGL!

I iti 4.

P

IPeh2'oT.

2.!.5,

I

r'-':E OF IF- ,Itt'

CI'E2.EAT !!E

FREED.Olt

NID ORIGI I A!i

TO BIE

other two alternatives and doesn't decrease much in likelihood with

age. at least before the age of 50.

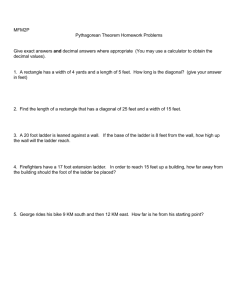

Examining the reward value of each form of promotion

separately produces some very interesting results.

The technical

ladder promotion is seen by young people of all three orientations

to be a reward for high performance.

Naturally it is those with a

technical ladder orientation who themselves feel more strongly about

this (Figure 7).

After the age of 40 however, there is, on the

average, general disagreement with the proposition that high

performance will lead to a technical ladder promotion.

This is true

to some degree even for those oriented toward the technical ladder

career.

_-

1

1

-

-

-

'P'

F*

* '; '

1

e

E

II

t'

~1 ~~~4.

;

=~~;

'_ 1

=··

f

_4C. if

.,:

.i

z

r..

c

if

-LL:

,:;

··

i·

:··

·

-1._

'i

···

r·.

i

i'(

I

4

i'

.I

i··

'''

:

.,i

E

.-.......

i

A

j E

i

-=

;r

.

`-.

r..r

=

::

- _

i

1·

·

4t:

'7P',:'i

:1 - .......

_ '-

j

'....'

;:

i[

i

.i-

.......

:-.

t/

it ..

:C.

I

·

'~~'

w

.

'

is

R

,

O~;;:.~t.;:"rL ._

_

_

,;

:

rJij

h

I

·

~~

'-

,s

] [ P .

sE i

J :fs

a _* i.

~~ ~~ i ~ ~ -' ~ii

:.

i

.

~~~7(

W¥""' :

./0

.

_

~

:f:.

."--'T.

I"t_

'©

_

I

I

1L_.

-, _

c.--, r~,r

O-:i ' TI i t

p R j H

: , i TI. -.t'

gIL

,_

1

f/

I

f }i'I

s E: s;:t4 )Ls

X

).

::t. I HTJEi;i-L'

At]rflrr.ms..t

*-

l---i·-----~------t----·--~-----

52.5

32 ,5

AfE

*f Z'

' : FP

--.i-.-tr'

F

-J. 3-.':PPFJ

--E------3-----------I

(YEATRS)

L TII ~ Ni s F r - Ii RDS j

F- i)

(r- A 1U0i)I

tCA6

FOR

3

i: ,i a

;

''il r E

T;

-17As for a management promotion coming as a reward for

performance only the managers really believe this to be true (Figure

8), and even their belief diminishes with time.

At no point,

however, do they disagree with the proposition.

Everyone else,

T

__-

I

0.5

.

P

.

?

..

.4:,-....

"E-

;&r<.>'

i'.

- ._-

"%.-

EGP1. EE OF

Ni GREE3EiT

' d'.

.

-'----

· . _--~

,

.

1.1

_"

' --- i

----

·

.,

.:'-?Ad.

-. . .

1

fail

(3i:;

i

1

.

%-L-;-

'* --1, -~ - --

'.'l . i'0

-'

-,,

-

,

r , ,- ( 1

x f lI 1"-"IT

I :I - i

T. 'I0-t

.0

1-

4

-5

5 2.

5

AG

(E

FIGUHRE 7.

GREE.iEN-T lITH THE

ST;TEhiEENT THAT

T THIGH PERY'ORtHf:CE

LENtDS TO TECuIi i .IiL

LAiDDiER

PRONOTIONF aS

FCTIO OF

CAREER OR Er T IO

I

particularly those engineers with a project orientation, disagrees

that a management promotion would result from high job performance.

Interesting projects are seen as a reward for performance by

those with the project orientation and by young engineers with a

technical ladder orientation (Figure 9).

Ii

-.

41

..

O

-i

-

42.5

!

>K1

*

hA.

'

,

'.-'

.

------i ._

...

:i

i

A.

-.

iii

t~~i~~tl:

X~~~~i~~f

-' i(1 I1I ,' 0II)-;.

Id

____-As

At no point or do those

-18--

with a managerial orientation agree with this possibility.

In general, with the possible exception of the technical

ladder oriented engineers, those with different orientations tend to

4

'r

%

.N

4--A-

-

14

?

-a,--

:I

-L

I

lk

sr-,- -4

t'

-.

M

""

-

iD. r, BdF

f

-

.i

-1

i

.

-

I

-------- r-------'

-

.i

-

~~ ~ ~

,..

-

i---

::+::-

Ma

3O:C

(

i

IS

jI

;t [!''

Ji

JT.-i",

T | , ,-L

.

.1

_~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~I

_.

i:

x--!

c.

-1

-! z

i. GE

s1

g *E.

t

iS

FI~SiJ~

-i- 1-F

88,

K1'

l

IT~1E hTT

i, 1 4:S-i T

R FUlHpCTiO4

ITH

3W

I

AGREEHEiT

E TGH

Ex 114T

A; G;R

iM

tiT Ht

HiA G;ERi

Ti!E

H

r

in

E

PF ORiHHHCE

AL PRO,11O i ON

OF CAi EER (RI EITAT ICN

see performance rewarded in the direction favored by their

orientation.

In the case of those inclined toward the technical

ladder this is true while they are young but diminishes considerably

with time.

Of course there is no way of filtering cause from effect

in these observations.

It may be that the perceived reward system

is the basis for the orientation.

On the other hand it may very

well be that the orientation is acquired for other reasons and

through a rationalization process the engineer comes to believe that

I-

I-`---

'-----

. !.

....

-19-

high performance will advance him in the desired direction.

Perceptions as a Function of Position.

Finally, grouping individuals as a function of their actual

position rather than orientation produces some interesting results.

Roughly 30 percent of the engineers already on the technical ladder

indicate a preference for that type of career trajectory.

On a

seven point scale, their degree of preference averages between 5.0

and 5.5 (Figure 10). Only about 10 percent of managers would prefer

a technical ladder career

Only for a brief period in their late

thirties do managers seem attracted by the relative freedom of the

technical ladder, but they recover from that fairly quickly.

1,5

I

.1

::

......

t

'

_

TEEE

F

d

ifiGEtEI1J

tET

i'

t

:

't

-r

'r

· :-TE tHlfit-L

Li!t)!-?

I E IT i iI .

_A

_,,,,,_--

d~;:2

'i

.4..~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~-.

et

-

A

G

.

I

P it

·. :-

..

/

-j.

-

2s2. 5

42

.5

52.5

AG F:

FIIiGRE 9.

iGREEMENT t11TH THE

; a:iiE

I 4T THT lIGIt PERF---R a1iCE

Lgi:

T- IttTERE:STIIIG PROQJECT

ciICI-HEtle aS i~ FIIt4CTiC11 6F

C-REER ORiE4T*ATiION

--

^1''--1----11I--I-------

·

r-'

;,. -:

-

AUJC.--' {ir!::

it i I f r(. ,t i

"" _, i:

"~~·I~1At

~-~.,~.i~A;["7: 1f

'1

Of

-20-

-

I._

I

i

-

'

,

I

C4

!

"I

,:

-

Wa

W

hi!

I

W I

l

! -*

n

=: =-ii

:

Q~c

i ._

'I-'l

_

I,

aC

#

fA,

ur

·I

9

=7

1-1

! -,-.iasi

fll"

;4

I~~~~~G ···V

i-

I

r..a

'a

1

i~~~~~~~~~~~.

I~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~ ~~~~~~~~~~

i

-r

a-.2taL

_____I

I_

II________

r~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~-

-~~

.arca.

*a

L·

-21When it comes to preference for a managerial career, managers

are uneqivocal

(Figure 11).

They rate it higher than anyone.

Interestingly. technical staff rate the managerial career higher

than do other engineers, particularly as they become older.

F

4

I,_

/1se

i

DESIRABILITY

OF

MANAGEMENT

.

L

r

-

i:e

_

-L:::::~'

]

4.5

~·-

-

:[ ! " .-

:

~:

.[

'I

sO t

th

iu i~

;id

i~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~"

/

,3

u~1~

*

*.

/

j

'

._

_ .

'45-' .5

iE

TIi-E R

0

.

F'

4!

ie

ii..

r

.,-' -·

-. -

-

_

-

1

-J

:

PHFE-EitE;E

PGi

FOR t ilii.Lr'

riL

C :

...

iiflC-'si

Lott

O

OF JOB CL',AS TFiCTltO:

i

Interesting project assignments increase in desirability for

all engineers, managers included as they age (Figure 12).

Although

younger managers do not seem to place a very high value on the

nature of the work, that they are asked to do, they eventually come

to feel almost as strongly about this as do their subordinates.

II

i

-22-

t

j

,,~~~~~~~~~~~~~_

!n&

ir

-,

3i:i.

::2 '~~....r_

_r

._

I's s.._.rt~~~.d

,Sf I : - TT_i

.lI,

'_

.|

-o

-i

=.

:..r.,.~

./,

,r

.__,

"'--.

............

,a ^./t

_

-i::

>-a

___ t_ _ _ _Or._

'Ir

· :- ECi

4

Ni,

r

4- M lqf-I

7,

T

14

_._.-

5

- - -

1.-

-32.. 5

.2.

FIGURE

A

P JEFEr

.FUII'-I-

__

_

__;

-,-c4.

-

·____

-2__

_

Rt-OI

__

1)

I-: E AIM,

_GJi4

tiCE I HTER;EST I i;

N

PRJECTS

AS

O.F JOB C.LASSIFICATION

CONCLUSIONS

It is very clear from the data that, while young engineers

generally seek managerial advancement, a substantial proportion

report a preference for what has come to be known as "technical

ladder" advancement in the organization.

Both of these more

career-oriented motivations decline with age and are replaced with a

desire for more interesting work content, without regard to

organizational.

An open question remains over the degree to which this results

from rationalization by those who have given up on the possibility

---`-'1-"111._1^11111_11_1_1

E.R

I

55

Cz:n2

C

1111..

---

1-___________--

's

;. ?

-23of promotion or whether it is a real change of attitude with age.

The latter could be the result of an increased awareness of the

costs (increased travel,

longer hours, administrative burden, etc.)

that are often associated with organizational advancement.

The existence of a substantial proportion of young engineers,

who indicate the "interesting project" preference and the fact that

engineers with this orientation differ significantly on several

other parameters, indicates that there is some underlying substance

distinguishing this group.

Managerially-oriented engineers differ

from those with a technical orientation, and project-oriented

engineers differ significantly from both of them.

The increasing concern for work is very important and largely

Work assignments for

neglected in the case of older engineers.

older engineers are often made with the implicit assumption of the

inevitability of technical obsolescence.

That inevitability has

been seriously challenged in recent years (Cf. Cole, 1979; Kaufman,

1975).

Furthermore such an assumption leads to work assignments

that are inherently less challenging and thereby create a

self-fulfilling prophecy, guaranteeing obsolescence.

Recent

research (Felsher, et. al., 1985) shows that instead of age being

the cause of obsolescence, that the failure of management to provide

challenging work and to emphasize the need for technical currency is

the more likely cause.

If older engineers seek more challenging

work and seldom find it, can there be any wonder over why they often

allow themselves to sink into obsolescence?

_______1_·_11___1___111_1_----

-24The present research results reinforce the formula for career

growth proposed by Katz (1982).- Older engineers can be challenged

by modifying job assignments and thereby forcing the acquisition of

new knowledge.

That. they seek this type of challenge is quite

evident in the data.

-25REFERENCES

Bailyn, L. (1980) Living with Technology:

Cambridge. MA: MIT Press.

Issues at Mid Career,

Cole, S. (1979) Age and scientific performance. American Journal of

Sociology, 8, 958-977.

Epstein, K.A.

(In preparation) Performance of the Dual Ladder in

industry, Doctoral Dissertation, MIT Sloan School of Management.

Felsher, S. M., T. J. Allen and R. Katz (1985) Technical

Obsolescence: Inevitability or Management Direction?, M.I.T. Sloan

School of Management Working Paper, No. 1640-85.

Katz, R. (1982) Managing careers: The influence of job and group

longevities. in Katz Career Issues in Human Resource Management,

Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall.

Kaufman, H. (1975) Career Management: A Guide to Combatting_

Obsolescence, New York: IEEE Press.

Krulee, G.K. and E.B. Nadler (1980) Studies of education for

science and engineering:

Student values and curriculum choice. IEEE

Transactions on Engineering Management, 7, 146-518.

McKinnon, P. (1980) Career Orientations of R&D Engineers in a Large

Aerospace Laboratory. M.I.T. Sloan School of Management Working

Paper 1097-80.

Moore, D.C. and D.S. Davies (1977) The dual ladder - establishing

and operating it, Research Management, 20, 14-19.

Ritti, R.R.

(1971) The Engineer in the Industrial Corporation, New

York: Columbia University Press.

Sacco, G.J. and W.N. Knopka (1983) Restructuring the dual ladder

at Goodyear, Research Management, 26, 36-41.

Smith, J.J. and T.T. Szabo (1977) The dual ladder - Importance of

flexibility, job content and individual temperment, Research

Management, 20, 20-23.