Building Disaster Resilience through Land Use Choices Ken Topping, FAICP

advertisement

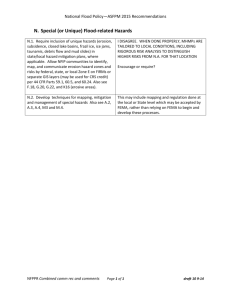

Building Disaster Resilience through Land Use Choices Ken Topping, FAICP Topping Associates International Land-use Decision Support: Reducing Risk from Hazards Simon Fraser University, Vancouver Friday, September 17, 2010 Land Use Planning – A Hazard Mitigation Tool Planning can be a powerful tool for mitigating natural and human-caused hazards Opportunities: – Increase disaster resilience – Prevent disaster losses – Avoid repetitive long-term post-disaster losses Challenges: – Create credible knowledge, science and mapping – Overcome economic and policy constraints When we build in the wrong places… or ways…Nature pushes back Wrong place: Landslide which killed 12, La Conchita, 2005, Ventura County…The second time in 10 years, except more killed Source: CGS Wrong way: Collapsed soft-story building, Loma Prieta Earthquake, 1989…There are 3,000+ of these in San Francisco Source: USGS • Challenge: build in the right ways and places …design is key! Terminology: What is a Hazard? FEMA: An event or physical condition that has the potential to cause fatalities, injuries, property damage, infrastructure damage, agricultural losses, damage to the environment, interruption of business, or other types of harm or loss Examples: – Earthquake – Floods – Wildfires – Landslides Source: 2010 California State Hazard Mitigation Plan Cascadia Subduction Zone Source: Natural Resources Canada Terminology: What is Risk? FEMA: The potential losses associated with a hazard, defined in terms of expected Probability Frequency Exposure Consequences Example: 100-year flood = 1% chance in a given year The catch – they can happen more frequently Source: FEMA Terminology: What is Vulnerability? FEMA: The level of exposure of human life and property to damage from natural and Oakland manmade hazards Example – narrow road where people died in 1991 Oakland Hills Fire Terminology: What is a Disaster? FEMA: A major detrimental impact of a hazard upon the population and the economic, social, and built environment of an affected area Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, Kobe, Japan, 1995 Disasters are the “New Normal” Disasters are increasing due to: – Natural hazards – Urban growth – Poor urban planning – Climate change Some communities are more vulnerable Mudflow, Venezuela, 1999 No community is immune Southern California Wildfires, 2003 New Orleans, 2005 What is Mitigation? FEMA: Mitigation = “sustained action to reduce or eliminate long-term risk to human life and property from natural and humancaused hazards” Examples include : – Building flood walls – Avoiding development in hazardous areas – Strengthening structures to withstand earthquakes New flood wall protects previously flooded mobile homes from Napa River, 2005, Yountville, California Mitigation Project Examples Distinguishing mitigation from preparedness Mitigation NOT Mitigation (i.e., preparedness) Flood walls and home elevations Sandbags and rescue boats Vegetation management and landscape ordinances Fire trucks, respirators, and radios Seismic building codes and building retrofits Family disaster supply kits and “go­bags” Terminology: What is Sustainability? Bruntland Commission: Sustainable development… …meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (Our Common Future, 1987) Sustainability = preservation of resources: environmental, physical, economic, social, cultural, historical Disasters destroy resources and make communities less sustainable Terminology: What is Resilience? Hazard: floods in City of Roseville The capacity of an community to: – – – Survive a major crisis or disaster Retain its essential structure and functions Adapt to post-disaster improvement opportunities Important to build resilience before a disaster After may be too late Library-Emergency Operations Center moved out of floodplain U.S. Federal Disaster Management Role The U.S. is very large and decentralized The federal government depends on states to play pivotal role States in turn rely heavily on cities, counties, and special districts (88,000 total) Disaster management laws and systems appear at all levels of government Wildland Fire Communities at Risk Source: USDA Forest Service and DOI National Flood Insurance Act (1968) Established National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) Provides private flood insurance backed by federal government Includes 100-year and 500-year floodplain mapping Community Rating System rewards better performing communities with lower flood insurance rates Stafford Act (1988) – Main Provisions Bottom-up emergency response/preparedness system: – Mutual aid governor’s emergency proclamation Presidential disaster declaration Individual and Household Assistance Program: – Basic disaster relief up to < $28,800 for 4-person household Public Assistance Program – Provides post-disaster infrastructure restoration grants Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) – Provides post-disaster hazard mitigation grants to prevent repetitive losses Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000 (DMA 2000) Purpose: reduce preventable, repetitive disaster losses Requires adoption of Local Hazard Mitigation Plans (LHMPs) as a precondition for receipt of federal mitigation project grants Adds new Pre-Disaster Mitigation (PDM) grant program mitigation projects designed to prevent disaster losses Encourages state and local mitigation capacity building through: – Financial incentives – Competitive applications DMA 2000: Hazard Mitigation Concepts Citizens pay for each other’s disaster losses ultimately Some losses are due to unwise local development decisions It is in everyone’s best interest for the federal government to build state and local mitigation capacity: – Federal government provides project grant funds to states and localities which adopt multi-hazard mitigation plans – Multi-hazard is most effective approach Mitigation is a good investment: – A study of FEMA mitigation grants from 1993-2003 found that for every $1 invested $4 of disaster losses were avoided Why Prepare an LHMP? FEMA requires LHMP as a condition of receiving both NFIP as well as DMA 2000 project grants, e.g.: – Flood Mitigation Assistance (FMA) grants (NFIP) – Severe Repetitive Loss (SRL) grants (NFIP) – HMGP grants (DMA 2000) – PDM grants (DMA 2000) – PA grants (DMA 2000) NFIP Community Rating System participation can lower flood insurance premiums up to 45% An LHMP can form the foundation of a community's longterm strategy to reduce disaster losses and break the cycle of damage, reconstruction, and repeated damage The planning process can be as important as the plan itself DMA 2000 LHMP Requirements 1. – 1. – – 1. – – – 1. Planning Process Documentation of the Planning Process Risk Assessment Identifying and Profiling Hazards Assessing Vulnerability Mitigation Strategy Local Hazard Mitigation Goals Identification and Analysis of Mitigation Actions Implementation of Mitigation Actions Plan Maintenance Process FEMA “How-To” Guides 2010 California State Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan Prepared by Cal Poly San Luis Obispo for Cal EMA - 2010 Plan nearing completion (Public Comment Draft online, pending final version) - Profiles and addresses mitigation strategies to counteract California’s natural and human-caused hazards - Recognizes climate change from global warming impacts, plus need to link climate action and “adaptation” policies and actions with hazard - Earthquake Hazards and Vulnerability Linking the LHMP & GP State General Plan Law Each county and city must adopt a comprehensive, long-term general plan for the physical development of the county or city... (§65300) General Plan Contents – The community's goals, objectives, and policies for development – A background data and analysis report – Maps and diagrams illustrating the generalized distribution of land uses, the road system, environmental hazard areas, the open space system, and other policy statements that can be illustrated The general plan acts as a “constitution for future development.” Lesher Communications v. City of Walnut Creek Linking the LHMP & GP 7 Mandatory Elements of the General Plan Land Use Housing Circulation Noise Conservation Open Space Safety Linking the LHMP & GP Safety Element Establishes policies and programs to reduce the potential risk of death, injuries, property damage, and economic and social dislocation resulting from fires, floods, earthquakes, landslides, and other hazards California State Laws Reinforcing Hazard Mitigation General Plan – integrated elements Zoning – must be consistent with General Plan Subdivisions - must be consistent with General Plan Building code Building retrofit laws Earthquake Fault Zoning Seismic Hazard Mapping Act – Seismic shaking – Liquefaction – Landslide areas Fire Hazard Severity Zones City of San Luis Obispo What’s Missing in this Picture? New Flooding Law – Assembly Bill 162 (2007) Most of downtown San Luis Obispo is in a 100-year floodplain Cities and counties must now address floodplains in general plan land use, conservation, safety and housing elements Land use element must annually review areas subject to flooding as identified by FEMA or DWR New DWR Handbook Risk Reduction in Land Use Decisions Timing is Everything Two critical points for mitigation: 1. General plan adoption — infrequent, farreaching 2. Subdivision approval — critical in hazardous areas If we miss the opportunity to mitigate at either point we create a “hazards multiplier” Multi­Hazard Case Study: Existing Conditions The General Plan Safety Element identified several potential hazards: e.g., the Dove Creek site is in a “High” wildfire area Dove Creek Hazard Mitigation Multi­Hazard Case Study: Existing Conditions The General Plan Safety Element shows a major fault to the east, capable of generating an M 7.0 earthquake The site has potential Earthquake liquefaction in the streambeds Dove Creek Hazard Mitigation Multi­Hazard Case Study: Existing Conditions The General Plan Safety Element showed a 100-year floodplain crossing the site in two locations Development was designed to mitigate flood and other hazards Dove Creek Hazard Mitigation Hazard Mitigation in New Development Key Land Use Mitigation Decisions: Refine federal-state hazard mapping Avoid development in hazard areas Deploy development setbacks Increase densities in safer areas Realign parcel and street boundaries to respect hazards Require multiple street entry-exit points for emergency access and evacuation Site Mitigation Evaluation Flooding/Seismicity + Engineered floodplain, Dove Creek Hazard Mitigation liquefaction analysis + Development set back behind 100-year floodplain boundary + Post-tensioned foundation system for liquefaction effects + Seismic structural code compliance Source: T. Yackzan photo Site Mitigation Evaluation Wildland Fires Dove Creek Hazard Mitigation + Project within 7 minutes of fire station + Impact fees paid to Fire Department + Fire code requirements met for structures + Fire sprinklers required in higher density areas Source: T. Yackzan photo Site Mitigation Evaluation Emergency Access ­ Overloaded cul-de-sacs in higher density area Dove Creek Hazard Mitigation - Lack of street continuity in higher density area - Insufficient turnaround areas - Cars parked in turnaround area no-parking zones Source: T. Yackzan photo Hazard Mitigation in Existing Communities Floodplain Property Buy Out Some Routine Strategies: Buy out hazardous properties and coastal wetlands Elevate structures in floodplains Add routes for emergency access-evacuation Use economic development, redevelopment, historic preservation as tools Source: City of Roseville Elevated home, New Orleans, January 2008 Source: K. Topping Building Codes Make New Buildings Safer Structural code requirements: part of California Building Code, now the International Building Code (January 2008) Structural code requirements apply to all new buildings Good News: Upgrading structural codes has made buildings stronger over time Bad news: Large remaining inventory of older vulnerable buildings Source: Professor James Mwangi, Arch. Eng. URM Retrofit Law: Progress in SLO 100+ URM buildings being strengthened SLO ordinance is mandatory Now most of way through Approach: economic asset protection Example: Railroad Square Building, SLO Statewide Progress SB 547 (1986) URM Building Retrofit Law Good News: 70% of Unreinforced Masonry (URM) buildings in California’s Seismic Zone 4 retrofitted in past two decades Bad News: Other structures needing retrofit: Soft-story apartments Tilt-ups RC-infill walls Houses not bolted to foundations Alquist-Priolo Earthquake Zoning Maps Affect Building Permits Earthquake Fault Zone Mapping Act – – Prohibits placement of buildings designed for human occupancy across active faults – Provides for maps of earthquake fault rupture zones (Holocene - last 11,000 years or less or more recent) – Proximity must be disclosed on real estate transactions Example: Hollister Area Source: California Geologic Survey Seismic Hazards Mapping Act State mapping areas susceptible to: - Liquefaction - Earthquake Induced Landslides - Ground shaking Susceptibility map of San Fransisco removed for transfer efficacy Local governments must use with building permit reviews Must also be disclosed on real estate transactions Areas Susceptible to Liquefaction, San Francisco Source: California Geologic Survey An Emerging Factor: Climate Change Adaptation = “Adjustments in natural or human systems to actual or expected climate changes to minimize harm or take advantage of beneficial opportunities” California Natural Resources Agency, December 2009 Climate Change Impacts: More and Bigger Natural Disasters Sea level rise Severe winds, storms Floods, landslides Wildfires Prolonged drought depleted water supply desertification Species changes Urban heat zones Agricultural disruption Source: Bay Conservation and Development Commission Temperature Increases 1961 – 2099 Rainfall Scenarios Less rainfall for Northern California means… …lower water supply for Southern California Wildfire Risk “The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal/Fire) spent over $500 million on fire suppression during fiscal year 2007/2008. “Larger and more frequent wildfires will impact California’s economy by increasing fire suppression and emergency response costs, damages to homes and structures, interagency post­fire recovery costs, and damage to timber, water supplies, recreation use and tourism.” Sea Level Rise Scenarios Current projection: 1.4 meters by 2100 Stay tuned… Projected Sea Level Rise at San Francisco Airport Light blue = 16 inches by 2050 Dark blue = 55 inches by 2100 Coastal Development Policy Choices Harden coastline – seawalls, levees Prohibit development in hazard areas – beachfront, bluffs, floodplain Improve evacuation Acquire coastal open space Re-engineer Infrastructure Elevate structures Source: EPA Coastal Land Acquisition Example: Fiscalini Ranch, Cambria Multi-use open space 437 acres $11.1 million cost 1.25 miles of coastline Pacific Ocean to downtown Cambria New water line extensions New access and evacuation route New Guidance Available FEMA/APA book - James C. Schwab, ed., Hazard Mitigation: Integrating Best Practices into Planning, Planning Advisory Service Report Number 560, May 2010 Forthcoming: Cal EMA and California Natural Resources Agency - Local Climate Adaptation Policy Guide Land Use Planning as a Hazard Mitigation Tool Opportunities: – Improve community resilience through better land use decisions – Reduce disaster losses through mitigation investments – Avoid repetitive long-term losses through pre-event action Challenges: – Expand knowledge base of stakeholders – Create credible science and mapping for wise land use – Utilize economic self-interest as leverage to overcome legal and political obstacles Advice from Roseville – Best Practices for LHMP Preparation 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Involve elected officials, community and the experts Find a champion in your agency – great opportunity as planner to work citywide Hire a good consultant (return on investment will be exponential) Communicate benefits constantly Leverage work done by others (state mapping, State Plan as resource) First steering committee meeting, August 2004 Take-away Points Wise community planning is essential to effective hazard mitigation Hazard mitigation is a good investment because it helps build resilience Communities can become more sustainable by addressing future land use planning with natural and human-caused hazards in mind