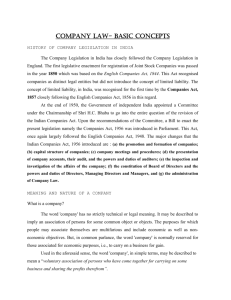

SALOMON’S CASE THE LAW DEALING WITH THE TORT LIABILITIES PERSPECTIVE

advertisement