UNFAIR CONTRACT TERMS: A NEW DAWN IN AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND?

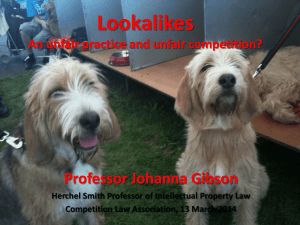

advertisement