THE POLITICS OF PAYDAY LENDING REGULATION IN AUSTRALIA

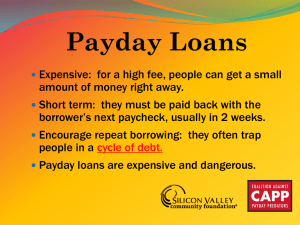

advertisement