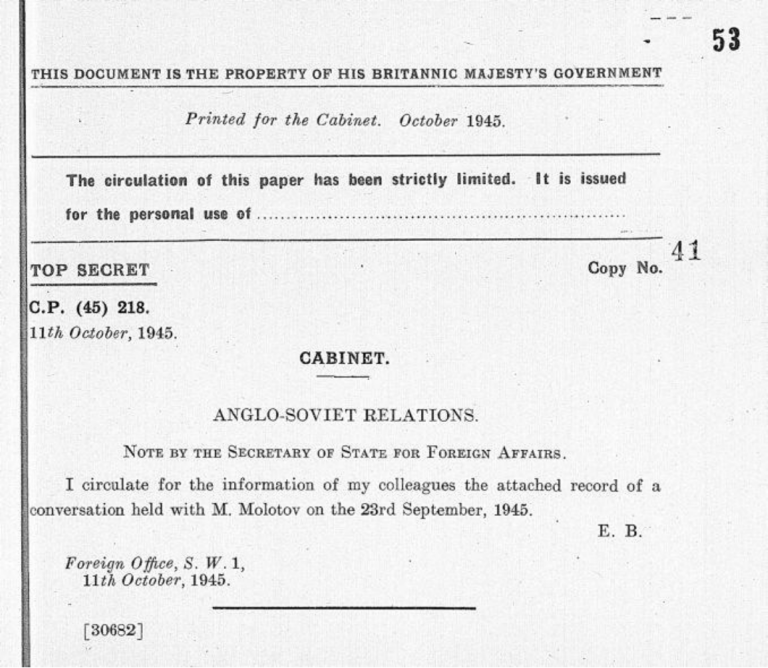

Printed for the Cabinet. October for the personal use of

advertisement

Printed for the Cabinet. October 1945. The circulation of this paper has been strictly limited. It is issued for the personal use of TOP SECRET ' Copy No. C P . (45) 218. 11th October, 1945. CABINET. ANGLO-SOVIET RELATIONS. NOTE BY THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN A F F A I R S . I circulate for the information of my colleagues the attached record of a conversation held with M. Molotov on the 23rd September, 1945. E. B. S.W.1, Foreign Office, 11th October, 1945. [30682] ANGLO-SOVIET RELATIONS. C O N V E R S A T I O N B E T W E E N T H E S E C R E T A R Y O F S T A T E A N D M. 23RD S E P T E M B E R , MOLOTOV ON THE 1945. T H E Secretary of State had a talk with M. Molotov a t the Soviet Embassy this afternoon. M. Gousev and I were present and M. Pavlov interpreted. T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E began by saying, that it seemed to him that our relationship with the Russians about the whole European problem was drifting into the same condition as that which we had found ourselves in with Hitler. H e was most anxious to avoid any trouble about our respective policies in Europe. He wanted to get into a position in which there was not the slightest room for suspicion about each other's motives. M. Molotov had quite rightly said that he wanted friendly neighbours and security in the east of Europe. Everyone who spoke to the Secretary of State about the West suggested that the Soviet Union was suspicious about a bloc directed against Russia. All that His Majesty's Government wanted was to collaborate with their neighbours without any offensive intention anywhere in Europe and to recover the rights which they had enjoyed before Hitler and for which they had fought. His Majesty's Govern­ ment would do nothing secret or enter into any arrangement against the U.S.S.R. with any offensive design of any kind. W h a t the Secretary of State wanted was frankness and friendliness. H e wanted to know precisely what was the Soviet policy in Europe so that every move made by His Majesty's Government need not provoke suspicion. If we made a treaty with France as a neighbour we did not want to be accused of creating a western bloc against Russia. We wanted both our neighbours and ourselves to be prosperous. T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E then turned to the question of Tripolitania and said that he had been told by Mr. Churchill that Marshal Stalin had said that Russia had no interest in the Mediterranean. He understood that there was no agreement to this effect but that Stalin had made some such statement. If His Majesty's Government knew what the U.S.S.R. wanted, the Russians would be told frankly whether or not it was acceptable to us and we would do our best to fit our policy into it. T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E then made two points to illustrate the kind of doubts he felt. H e could not understand why M. Molotov could not be frank about the Dodecanese. About the inland waterways all he wanted was that we should get back what we had lost, i.e., our international rights. He ended by saying that he was not willing, indeed he would not go on with a conference in which it was impossible to deal frankly and in a friendly way with each other. If M. Molotov would tell him frankly what was in his mind, what we were expected to agree to, the Secretary of State would lay all his cards on the table with equal frankness. M. MOLOTOV said t h a t he would begin by referring to what the Secretary of State had said about Hitler, perhaps rightly or perhaps wrongly. T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E broke in to say that he did not wish the talk to start with a misunderstanding. He had not wanted to suggest that the U.S.S.R. in any way resembled Hitler. All he had wished to suggest was that absence of frankness led to situations which became irretrievable. M. MOLOTOV said t h a t he understood. Hitler had looked on the U.S.S.R. as an inferior country, as no more than a geographical conception. The Russians took a different view. They thought themselves as good as anyone else. They did not wish to be regarded as an inferior race. He would ask the Secretary of State to remember that our relations with the Soviet Union must be based upon the principle of equality. Things seemed to him to be like this : there was the war. During the war we had argued but we had managed to come to 10916-845 [ 3 0 4 5 0 - 3 ] B terms, while the Soviet Union were suffering immense losses. At that time the Soviet Union was needed. But when the war was over H i s Majesty's Govern­ ment had seemed to change their attitude. Was that because we no longer needed the Soviet Union ? If this were so it was obvious t h a t such a policy, far from bringing us together, would separate us and end in serious trouble. M. M O L O T O V then turned to the Dodecanese and. said it was a n issue of no importance. H e felt sure that there was room for agreement and that Greece would get the islands. But what about the bases in Constantinople which the Russians had suggested? When this question had been raised in Berlin their proposals had been flatly rejected. But during the last war we had offered Constantinople to the Czar. We need not assume that his Government had had or had now any claims on Constantinople. This was not so. W h y were we so concerned about the Straits which were the entrance to an inland Soviet sea and an area of the highest importance to the security of the Soviet Union ? Turkey could not defend the Straits alone and we did not want the Russians to come to terms with the Turks. Our present attitude was " far w o r s e " than the treat­ ment we had given the Czar during the last war. We wanted the Turks to hold Russia by the throat and when the Russians had asked for one trusteeship in the Mediterranean we had felt t h a t she was encroaching on our rights. But we could not go on holding a monopoly in the Mediterranean. Italy was no longer a great Power. Prance had dropped into the background. W e were alone in the Mediterranean. Could we not at least find a corner for the Soviet merchant fleet ? I t was very hard to understand. M. MOLOTOV then turned to the inland waterways " a s a purely European affair." I t seemed to him much better to regard it in the light of a temporary situation to persist only during the period of occupation and until the peace treaties were signed with the satellites. If it were settled on this basis the supreme authorities should be the appropriate Commanders-in-Chief. Otherwise authority would be divided and friction would occur and things would become damaging alike to us, the Russians, the French and the Americans. M. M O L O T O V ' s next point was about our policy in the Balkans. It seemed to him that an offensive was being conducted against the Soviet Union in order to " unleash antagonism in the Balkans." M. MOLOTOV then said that we persisted in declining to recognise White Russians and Ukrainians as citizens of the U.S.S.R. although we had agreed to the Curzon Line. H e did not w a n t to dwell upon these questions, but about Germany, our common foe, instead of helping them with reparations we were p u t t i n g difficulties in the way. We did not want any reparations. H e wished t h a t we did. A t the same time we were not allowing the Russians to take any, even in the present case, where our common foe was in question. He did not wish in this connexion to mention Field-Marshal Wilson's statement which had been hostile to the Soviet Union. Finally, there was the question of the Far East which the British Ambassador in Moscow had raised with him on the 14th August, suggesting that it would be an appropriate matter for discussion in London. But it had not been discussed and it was a subject which called for frank and frcc discussion I n reply, T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E said he wished to deal with the point M. Molotov had made about equality. I t was in matters like this that misunderstandings arose. Whatever the Germans had thought about the Russians it had never entered his head, in fact, it had never entered the heads of any member of the Labour P a r t y , to regard the Russians as an inferior race. I n fact, the P a r t y ' s view had been quite otherwise for many years. Neither he nor any of his colleagues approached the Soviet Union with any sense of superiority, nor, indeed, with any sense of inferiority. But in this country there was a growing feeling that the tables had been turned and that we were being treated as inferiors both by the Russians and the Americans. M. MOLOTOV denied this so far as his people were concerned. T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E said that, nevertheless, it was common belief here, and he suggested that the subject should be " taken off the agenda." W e would never allow ourselves to think about the Soviet Union in such terms or to approach any common problem with such a thought in our minds. Was t h a t agreed? M. M O L O T O V said yes T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E then said that he wished to deal with the Mediterranean and the Straits. He had not discussed the Straits with anyone or investigated the question since he had been in office. What M. Molotov had said about the Czar was true. H e remembered it well. There had been some discussions about the fact that the Turks were mobilised because of their fear of Russia which had sprung from alleged press attacks. He was quite willing, so soon as he could, to study this problem afresh. He had not even had time so far to mention it to the Chiefs of Staff or any military authorities. On the other hand, about Tripolitania, H i s Majesty's Government did not want a monopoly. As M. Molotov has described the position of the Straits as a strangling of the throat of the Soviet Union, the British Common­ wealth had a tremendous fear of anything happening in the Mediterranean which might, so to speak, cut the Empire in half. If he had to deal with this question purely in the light of British interests he would give the trusteeship of Tripolitania to Italy, but he would want the trusteeship of Cyrenaica, because of its vital importance to Egypt, where his responsibilities were great. H e was not in search of wealth, for the country was nothing but sand. He was thin king purely in terms of security. M. MOLOTOV said : " let us agree." T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E replied that there had been a decision in the Council, to which M. Molotov answered that he was not aware of any decision and that he was ready to support Great Britain if it was necessary. T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E then turned to Eritrea and said that we had wanted to group these territories together and to keep them demilitarised, giving Abyssinia an outlet to the sea. That ought not to have been hard. I t was a purely British interest and that was how he would like to have seen i t settled. H e was putting all his cards on the table face upwards. As to the Dodecanese he wanted them to go to Greece. Whether or not they were demilitarised was a question for the Security Council, but he did not want to see them used by any Power in a way which would cause trouble or suspicion to the Soviet Union. Turning to inland waterways, he explained that these free and open waterways had sprung largely from the old 19th century British free trade policy, just as we had tried to maintain the freedom of thtf seas for everybody. We were a maritime nation and all we asked was that, when a permanent regime was set up, our position would be restored. He was ready to consent to a temporary regime, and that was why he had not discussed M. Molotov's paper last night. H e had thought it better to study it. There­ fore, if it were agreed in principle to restore to us, within a reasonable time, what we had lost, say two or three years, his doubts would be at rest. He thought that to fix the temporary regime to last as long as Allied control would be a mistake, because no one knew for how long this control would exist. M. MOLOTOV replied that it would be well to settle questions of common interest. T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E then said that M. Mototov had suggested that we wanted to stir up the Balkans (M. Molotov broke in to deny this). He could give the utmost assurance that this was not so. H e had inherited the trouble about General Radescu. But there had been a feeling that the Bulgarian and Roumanian Governments were difficult. There had been many irritations. That was why the other day he had tried, in quite good faith, to suggest some method to clear the situation up. M. Molotov had a t once assumed that this suggestion was directed against himself, but this was a mistake. The Secretary of State would have been just as willing to have an independent enquiry in order to see if our policy in the Balkans was wrong too. So when it was proposed that we should base ourselves purely upon the reports of our men on the spot, this seemed to offer no escape, for the reason that our respective and conflicting views were based upon these reports. M. MOLOTOV suggested that these reports should be checked more closely. We were at liberty to send any men we trusted and who would be dispassionate, but please not one who had harboured General Radescu. T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E asked whether such a man would be able to check up with the Soviet representatives on the spot. To this M. MOLOTOV said yes, and the Secretary of State added that all he wanted was to dispel irritation. [30450-3] B2 T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E then reminded M. Molotov that he had mentioned the White Russians and Ukrainians. Did this include citizens of the Baltic States? M. MOLOTOV said no, this was a separate question which would need discussion. T H E S E C R E T A R Y O F S T A T E claimed that we should have to limit ourselves to people who were willing to return to the Soviet Union. To this M. MOLOTOV said t h a t the question was whether we regarded these people as Soviet citizens. T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E asked whether they were, indeed, Soviet citizens before the peace treaty was ratified. M. MOLOTOV claimed that they were, and unquestionably so in the light of what we had signed. T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E immediately asked what we had signed and s i g n e d " in the Crimea. THE M. MOLOTOV referred to what had been S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E reminded him t h a t we had done no more than to say (that we would support the Curzon Line, and added that he had been advised t h a t until this Line was ratified he could not turn the people in question out. M. MOLOTOV clung to his claim that, having subscribed to the Curzon Line, we were obliged to recognise these people as Soviet citizens. W h a t did we think t h a t they were ? T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E suggested that they had become stateless, to which M. MOLOTOV replied t h a t this meant that we were with­ drawing our signature and making 13 million [sic] people stateless. T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E asked what he was to do about the people who did not w a n t to go. Was he to drive them on to a ship \ M. MOLOTOV said that what he wanted was that we should declare that we regarded them as Soviet citizens. T H E S E C R E T A R Y O F S T A T E said he would have the whole thing looked u p to-morrow, meanwhile he thought t h a t he had p u t in a paper on the subject to the Council. M. MOLOTOV said that he had received this paper, and that it had surprised him, to which T H E S E C R E T A R Y O F S T A T E said that it was better to begin by surprise and then to clear the whole thing up. I t was not a question of policy. M. MOLOTOV insisted that it was, because the people concerned were Soviet citizens. T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E said that, if what M. Molotov said about our having signed an agreement about the Curzon Line were correct, he had no answer. If on the other hand our legal position were correct, he found himself in a difficulty. M. M O L O T O V said t h a t our people had played us false, as they had done in the matter of a recent translation, about which there had been a bad, even a dangerous, mistake. l i T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E then turned to reparations, and reminded M. Molotov that at Berlin he had agreed to a period of six months. M . . M O L O T O V said t h a t two months had already gone by and nothing had happened. T H E S E C R E T A R Y O F S T A T E said that he understood t h a t there had been some question about the place in which the Commission should work. Moscow had been found inconvenient and Berlin had now been suggested. M. MOLOTOV said he did not want to argue about that, but he must point out t h a t the Commission so far had not done " a damn t h i n g . " T H E S E C R E T A R Y O F S T A T E said that he had instructed his people to finish the job within six months. M. MOLOTOV suggested t h a t they were frustrating this policy, to which T H E S C E R E T A R Y OF S T A T E replied that they would not be allowed to do so. An agreement was an agreement. H e had spoken to Mr. Attlee this morning because the matter was also a Treasury one. Instructions would be issued that the agreement must be scrupulously kept. T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E then mentioned the story about Field-Marshal Wilson and explained that he had repudiated the statement that h a d been made. To this M. MOLOTOV suggested that the Foreign Office was washing its hands of the matter and he was informed by the S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E that it was being dealt with by the Ministry of Defence. M. MOLOTOV then asked me whether I could tell the Secretary of' State how a Russian Marshal would have been dealt with if he had ventured to make a similar statement about Great Britain. I knew he would have very short shrift. The Far East was the Secretary of State's next point. The matter was not on the agenda. H e had expected it to be raised and had told M. Molotov so, but nothing had seemed to happen about it. M. MOLOTOV recalled that he had raised it and had been alone in doing so. T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E remembered t h a t he had been in the Chair, but had said that he had no paper to put in. A t the time things had been moving too fast in connexion with the surrender of J a p a n . He had felt sure that before the Conference was over something would be said. He did not know what had happened, but he fancied there had been some discussion about it. M. MOLOTOV asked whether His Majesty's Government thought that a Control Commission was necessary in J a p a n . T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E said that it had been suggested and asked M. Molotov whether he wanted it. For himself he had not been enthusiastic. M. MOLOTOV replied that he did not think that the Americans could be left in such complete mastery in the F a r East as to exclude anyone from a share in the proceedings. They could not tackle the matter alone. T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E said he did not wish to be indiscreet, but he would like to know whether M. Molotov had discussed the matter with Mr. Byrnes. M. MOLOTOV said no, but it was a very important one. T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E said he would think it over. M. Molotov reminded him that the British suggestion had been to the effect that the Soviet Union, the United States, China, the Australians and ourselves should all have a hand in it. Something on these lines would be acceptable to the Russians, who were convinced that the Americans would be very hard put to it to do it all alone. T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E asked if M. Molotov had it in mind that there should be no centralised zones. To this M. MOLOTOV said yes, adding that he was ready to accept something on the lines of the British suggestion. A t this point T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E said t h a t he would like to go back to France. M. MOLOTOV said that he had asked M. Bidault to call on him this evening^ T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E said that the Cabinet had come to no decision about a Treaty with France. We did not want in our approach to this question to cause any suspicion. But we did feel t h a t in the interests of our two countries which were so close together and had a similar standard of living and so on, it would be best for everyone concerned, including the Soviet Union, if we had a treaty with France on the same lines as that with the Soviet Union. We did not want to create—(and he rejected the term—a western bloc. He would say so in the House of Commons. He did not like any kind of slogans—western blocs or eastern blocs. H a d M. Molotov any objection to such a Treaty ? M. MOLOTOV replied that he had not and never had had. We should not attach too much importance to what " irresponsible Soviet news­ papers " said about this matter; and he reminded the Secretary of State that the Soviet Government had consulted us before signing a treaty with France. T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E reiterated his enquiry whether the Soviet Government had any objection. M. MOLOTOV replied t h a t he would report to his Government and that he would like to be able to tell them that the purpose of the treaty would be the same as t h a t of the Anglo-Soviet Treaty—-that was to say against German aggression. H e did not foresee any kind of objection. T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E said t h a t no negotiations had been opened with France, but he would soon be asked about the matter in the House of Commons. The Cabinet would therefore have to decide. That was why he had brought the question up with M. Molotov. In conclusion, T H E S E C R E T A R Y OF S T A T E said that he thought the talk had been a useful one. M. MOLOTOV agreed, and said that any time the Secretary of State wished to talk he would be glad to join him. He had come to this country not only to attend the official meetings of the Council, but also to have such conversations as the present one. 1 A. C. K. 22rd September, 1945.