5 R&D Activities of Foreign and National Establishments in Turkish Manufacturing

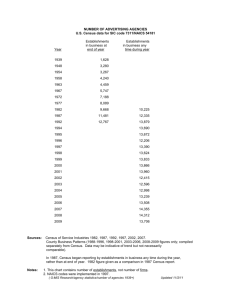

advertisement