Document 11235884

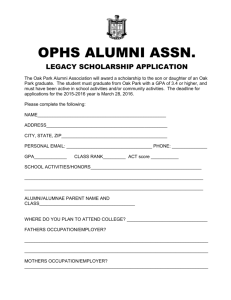

advertisement