Document 11235883

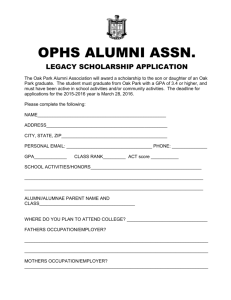

advertisement