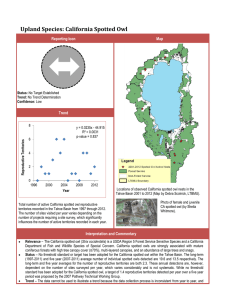

Background and the Current Management Situation for the California Spotted Owl

advertisement