Odyssey Papers 2 Victory Lost in the English Channel, 1744.

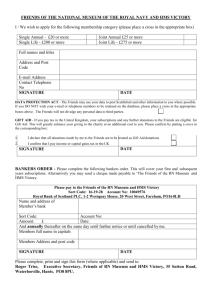

advertisement