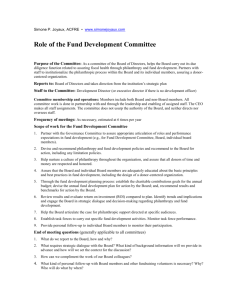

soc i a l w e l f a r... r e s e a r c h ...

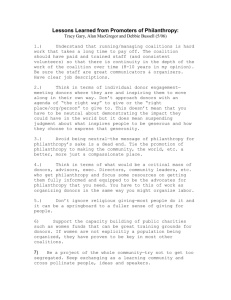

advertisement