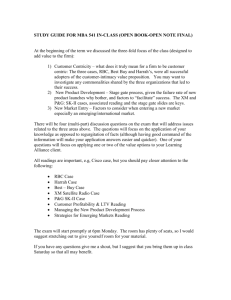

Document 11222671

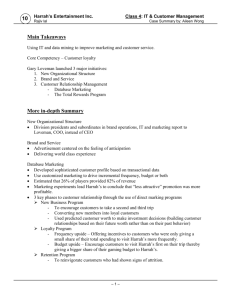

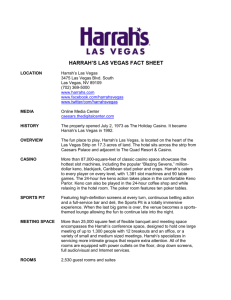

advertisement