CC2: Becoming a Master Teacher ‐Developing Cri9cal Habits of 5/9/11 Mind. Lindner, R. & LaPrad, J.

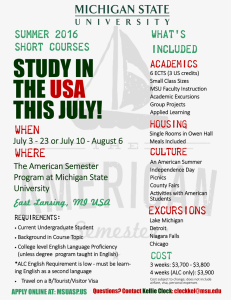

advertisement

CC2: Becoming a Master Teacher ‐Developing Cri9cal Habits of Mind. Lindner, R. & LaPrad, J. 5/9/11 “It would be helpful if there were predictable phases of teacher development that could guide educators.” ‐ Hammerness, K., Darling‐ Hammond, L., Bransford, J, Berliner, D., Cochran‐Smith, M, McDonald, M. & Zeichner, K. (2005). How teachers learn and develop. In, L. Darling‐Hammond & J. Bransford, Eds. Preparing teachers for a changing world: what teachers should learn and be able to do. Jossey‐Bass. “As differences between experts and novices accumulated in educa:on and other fields, it became apparent that there was a need for a theory of development to describe the transi:on from novice to expert.” ‐ Berliner, D. C. (2004). Describing the behavior and documen9ng the accomplishments of expert teachers. Bulle7n of Science, Technology & Society, 24, 1, 200‐212. “Exper:se can be fostered by making the exper:se trajectory visible to learners through models of exper:se…” – Lajoie, S. P. (2003). Three stage models: Glaser, Anderson, Alexander Anderson – cogni<ve, associa<ve, autonomous Glaser – externally supported, transi<onal, self regulatory Alexander – acclima<on, competence, proficiency (MDL) Five stage model: Berliner (Dreyfus & Dreyfus) Stage 1: novice Stage 2: advanced Beginner Stage 3: competent Stage 4: proficient Stage 5: expert 1. “Student teachers and many first year teachers are ordinarily considered to be novices.” ‐ Berliner, 2004, p. 206. This seems to suggest a minimal role for teacher prepara<on in the developmental path of exper<se and, again, emphasizes <me and experience as the dominant factors in the development of exper<se. 2. “The problem is not how to turn novices into experts faster or with less work. The problem is how to ensure that novices develop into experts rather than into experienced nonexperts.” ‐ Bereiter & Scardemalia, 1993, p. 18 1 CC2: Becoming a Master Teacher ‐Developing Cri9cal Habits of Mind. Lindner, R. & LaPrad, J. 5/9/11 From Novice to Expert: Developmental Phases in Becoming a Master Teacher (Adap<ve Expert)* “Experts, like other humans, are not all alike.” – Berliner, D. (2004), p. 203) Rou<ne exper<se * Quick and accurate solving of familiar problems * Modest capaci9es of dealing with novel types of problems Key factors in development * Observa9on and imita9on * Experience and repe99on under controlled condi9ons Adap<ve exper<se * Effec9ve solving of novel problems * Genera9on of new procedures and prac9ces from expert knowledge * Deep conceptual understanding Key factors in development * Repeated prac9ce of skills and procedures under varying condi9ons * Need for explana:on (not just doing) – seeking for principles. * Explicit learning goal or inten:on (intent to reach beyond current level of performance) (Hatano & Inagaki, 1986) The Importance of Prepara<on for Teaching “…evidence…suggests that teachers’ development is influenced by the nature of the prepara<on they receive ini<ally…” – Hammerness, Darling‐Hammond, Bransford, Cochran‐Smith, McDonald & Zeichner, 2005. The model we are proposing seeks to ar<culate what is, and needs to be, happening in the early stages of exper<se development and the role such prepara<on plays in the likelihood that full exper<se is eventually aaained. At this level we are dealing with an individual who thinks he/she might want to become a teacher. Of course, different individuals come with different backgrounds, but these individuals typically share a naïve concep<on of the profession and their level of commitment is not yet deep. The primary focus of this phase should be on the development of basic skills to the highest level possible, and perhaps acquiring a general understanding of the nature and expecta<ons of the teaching profession. In terms of knowledge, skills, and disposi<ons, we want students to be developing high levels of literacy and numeracy, a broad and general knowledge and understanding of science, literature, history, different cultures, etc. The abili<es to read, write, compute, communicate, and reason should be clearly established and well developed. Lastly, we look for an overall commitment to learning and self‐ improvement in general that is consistent and goal oriented. 2 CC2: Becoming a Master Teacher ‐Developing Cri9cal Habits of Mind. Lindner, R. & LaPrad, J. This individual has taken the next step. His, or her, professional knowledge and understanding of core subject maaer (or domain, if secondary educa<on) is deepening. The focus turns to acquiring pedagogical knowledge, skills, and disposi<ons as individuals are ini<ated into the tasks, challenges and commitments they will confront as future teachers. The ini<ate has met requirements for entry into teacher educa<on, has a loosely developed, emerging knowledge of the profession based on personal experience and ini<al course work, his misconcep<ons are fewer but not fully eliminated, and he has made a basic commitment to enter the profession. Given that his/her basic skills and general knowledge base are well developed, the focus turns to developing deep content specific knowledge as well as a sound professional core, and preliminary development of pedagogical skills. The ini<ate possesses an emerging understanding of learners and learning, the importance of cultural context and background, and related core professional knowledge. The candidate has accumulated the knowledge and skills, and developed the disposi<ons, needed to enter the profession of teaching. She/he has had the opportunity to apply the knowledge, skills, and disposi<ons he has acquired in increasingly complex and varied field sehngs and is prepared to manage the demands of a classroom at a rudimentary level using basic rou<nes developed during student teaching and learned in the classroom. However, the ability to improvise and adapt to unusual circumstances is limited and underdeveloped. Equipped with the right habits of mind and disposi<ons, the candidate, with appropriate support and mentoring, can navigate the complex world of the classroom successfully at a basic level. The candidate has accomplished all that is necessary to be worthy of ini<al cer<fica<on. 5/9/11 “Metacogni:on is an especially important component of adap:ve exper:se.” ‐ Hammerness, K., et. al. (2005). Having acquired some pedagogical (general and content specific) training, content specific understanding, and a basic grasp of the social, cultural, professional and ethical challenges of classroom life, the appren<ce is prepared to begin working in the classroom under supervision. The focus now turns to prac<cal applica<on of the knowledge and skills acquired in the classroom to real situa<ons and sehngs that approximate the demands of the profession. Most misconcep<ons (though not all) regarding the profession are now gone and the appren<ce is in the process of becoming aware of the reali<es of the demands of the profession. Beyond acquiring many basic rou<nes, developing the mental habits of self‐analysis, reframing, self‐explana<on, and self‐ monitoring during this phase are cri<cal in terms of the long‐term development of teachers. To get from phase I to Phase IV, a curricular mechanism is required. At one level, of course, this is the specific teacher prepara<on program of a given ins<tu<on. However, this is not very specific in terms of what exactly is being learned both in terms of the ul<mate goal and the steps along the way. To achieve greater specificity, we are in the process of adap<ng and adop<ng the idea of a learning progression (LP) from science educa<on. This allows us to specify what the final objec<ve is, in terms of “big ideas” or principles, and the intermediate steps that will, hopefully, produce the desired result. But that’s a topic for another day. For now, we will just focus a few of the key characteris<cs of a program designed to produce the kind of exper<se we are ajer. 3 CC2: Becoming a Master Teacher ‐Developing Cri9cal Habits of Mind. Lindner, R. & LaPrad, J. Reduc<ve problem solving is a process of reducing problems to tasks that can be handled by simply following the rou<ne procedures that do away with whatever challenges a problem, or set of problems, may pose for the learner. * Prac<ce and refinement of exis<ng procedures * Some <nkering may be required (no two situa<ons are exactly alike) * Highly situated (implicit cogni<on) 5/9/11 Progressive problem solving is a process of genera<ng expert knowledge through the con<nual reinvestment of mental resources into addressing problems at higher levels. * Reinvestment in learning * Seeking out more difficult and challenging problems * Forming more complex representa<ons of recurrent problems * Requires nonsituated cogni<on (explicit cogni<on) “Problem reduc<on reflects the commonplace view of problems as things to be goaen rid of, to be reduced in number and severity. It also represents a common way in which problems are handled, by reducing them to tasks that can be handled with rou<ne procedures.” (Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1993, p. 99) “…mental resources, as they become available, are reinvested…leading to further growth in skills and knowledge. This, we propose, is the process whereby people move beyond the plateaus of normal learning and acquire exper<se.” (Bereiter & An analogy might be useful here. In terms of fitness, such an approach will probably get you into, and keep you in decent shape, but it won’t turn you into an athlete. Developing rou<ne exper<se is, to a degree, necessary but it is not sufficient for developing adap<ve exper<se. This is what we are ajer. An important characteris<c of progressive problem solving is the undertaking of increasingly more challenging problems and a willingness to accept working at the edge of one's competence. Informal knowledge – factual informa<on and skills acquired experien<ally resul<ng in implicit understanding (largely situated, based in prac<ce). Impressionis:c knowledge – similar to informal knowledge but refers to your sense of people and events; more a feeling than ar<culated knowledge (also largely situated, prac<ce based). Scardamalia, 1993, p. 92) According to Ericsson (2006, p. 685) “…extensive experience of ac<vi<es in a domain is necessary to reach very high levels of performance. Extensive experience in a domain does not, however, invariably lead to expert levels of achievement…further improvements depend on deliberate efforts to change par<cular aspects of performance.” Self‐regulatory knowledge – your understanding of yourself as a learner, and the varying demands associated with learning tasks, and the ability to use such knowledge, in a controlled fashion, toward the furtherance of learning goals. Formal knowledge – knowledge and learning that is text and school based; explicit knowledge that has been objec<fied and abstracted (non situated). The argument here is that formal knowledge is not necessarily opposed to informal and impressionis<c knowledge; it ideally enriches and focuses such knowledge. For that to happen, however, it must become integrated with the other types of knowledge. ‐ (Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1993). * Inclusive of declara<ve and procedural (content, pedagogical, and pedagogical content) knowledge. In any case, knowledge maaers. The image above (from Ericsson, 2006) captures the rela<onships between different levels of experience and prac<ce. Reaching the expert level requires focused, deliberate, effornul prac<ce over extensive periods of <me. 4 CC2: Becoming a Master Teacher ‐Developing Cri9cal Habits of Mind. Lindner, R. & LaPrad, J. 5/9/11 What’s the difference between rou<ne prac<ce (repe<<on) and deliberate prac<ce? Deliberate prac<ce IS: (Ericsson, 2006) “The key challenge for aspiring expert performers is to avoid the arrested development associated with automa<city and to acquire cogni<ve skills to support their con<nued learning and improvement. By ac<vely seeking out demanding tasks – ojen provided by their teachers and coaches – that force the performers to engage in problem solving and to stretch their performance, the expert performers overcome the detrimental effects of automa<city and ac<vely acquire and refine cogni<ve mechanisms to support con<nued learning and improvement…” ‐ Ericsson, 2006. The cri<cal ques<on ‐ How do we develop both the opportuni<es for engaging in (1) progressive problem solving and (2) deliberate prac:ce, and the disposi<on necessary to sustain them, into our courses and programs? How do we help our candidates exercise, and develop an appe<te for, these cri<cal components of the path to (adap<ve) exper<se? Examples anyone? Inten<onal and relevant to the skill being prac<ced (improper prac<ce can actually make you worse!) Effornul, requiring aaen<on and concentra<on from the learner (involves challenge and focus) Targeted, specific and sustained (aimed at elimina<ng specific weaknesses) Pitched at a level just beyond current reach (based on careful observa<on, analysis, and diagnosis) Ojen involves ac<vi<es selected by a coach or teacher to facilitate learning (It’s ojen hard to be objec<ve about oneself, and hard to no<ce everything that might be relevant; provides cri<cal feedback) Deliberate prac<ce is NOT? (typically) Inherently enjoyable (hard WORK; long term, achievement based, reward) Taking a class or workshop (although they might include some deliberate prac<ce in them) Aaending a lecture or discussing something with an expert (although inspira<on may follow) Simply reading an ar<cle or a book (unless you try out and test some of what you read) Simply watching an expert perform (unless you are fairly skilled to begin with and you apply what you learn) Teaching or any other form of actually performing your skill 1. 2. 3. 4. Building a solid founda<on of basic skills and content knowledge Elimina<ng misconcep<ons (correct knowledge maaers) Providing opportuni<es for prac<ce under varying condi<ons Elici<ng explana<ons (beyond doing; reflec<on), encouraging self‐ explana<on (understanding also maaers) 5. Focusing on reframing and re‐representa<on of tasks, issues and problems (another aspect of reflec<on; progressive problem solving) 6. Encouraging deliberate prac<ce (highly relevant; significant effort) 7. Incrementally increasing the challenge level (progressive problem solving) 8. Fostering self regula<on (internalizing control) 9. Promo<ng con<nual reinvestment (affect and mo<va<on) 10. Suppor<ng risk taking 11. Appealing to the heroic element 12. Crea<ng a culture that supports the development of exper<se 5 CC2: Becoming a Master Teacher ‐Developing Cri9cal Habits of Mind. Lindner, R. & LaPrad, J. 1. The novice to expert framework allows us to frame teacher prepara<on as a logical, coherent and visible sequence 2. Great teachers are made, not born 3. Prac<ce and experience alone do not produce exper<se 4. In short, in determining ul<mate outcomes, (type of) prepara<on maaers 5. Both situated and nonsituated cogni<on is required for the produc<on of (adap<ve) exper<se (theory and prac<ce) 6. Prepara<on should be focused on producing adap:ve, rather than simply rou<ne, exper:se (although both are necessary) 7. Exper<se is developed and takes considerable <me and investment to achieve (5‐10 years) 8. Generally speaking, it takes a culture of exper<se to sustain the development of an expert 9. Although adap<ve exper<se leads to greater adaptability and flexibility, there is no such thing as a general expert (domain specificity is the rule in exper<se) Alexander, P. A. (2003). The development of exper9se: the journey from acclima9on to proficiency. Educa7onal Researcher, 32, 8, 10‐14. Bereiter, C. & Scardamalia, M. (1993). Surpassing ourselves: an inquiry into the nature and implica7ons of exper7se. Chicago, IL: Open Court. Berliner, D. C. (2004). Describing the behavior and documen9ng the accomplishments of expert teachers. Bulle7n of Science, Technology & Society, 24, 3, 200‐212. Berliner, D. C. (1994). The wonder of exemplary performances. In, J. N. Mangieri and C. Collins, Eds. Crea7ng powerful thinking in teachers and students. Ft. Worth, TX: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. Darling‐Hammond, L. (2006). Construc9ng 21st‐century teacher educa9on. Journal of Teacher Educa7on, 57, 10, 1‐15. Dreyfus, H. L. & Dreyfus, S. E. (1980). A five‐stage model of the mental ac7vi7es involved in directed skill acquisi7on. ORC‐80‐2. Opera9ons Research Center, University of California, Berkeley, pp. 1‐18. Dunn, T. G. & Shriner, C. (1999). Deliberate prac9ce in teaching: what teachers do for self‐improvement. Teaching and Teacher Educa7on, 15, 631‐651. Ericsson, K.A., Charness, N., Feltovich , P.J.. & Hoffman, R. R. Eds. (2006). The Cambridge handbook of exper7se and expert performance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Ericsson, K. A. (2006). The influence of experience and deliberate prac9ce on the development of superior expert performance. In, K.A. Ericsson, N., Charness, P.J., Feltovich, & R. R. Hoffman, Eds. The Cambridge handbook of exper7se and expert performance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 5/9/11 1. Is the genera<on of adap<ve (as opposed to rou<ne) exper<se a reasonable goal for teacher prepara<on? 2. Is teaching a field prepared to view itself in terms of the development of exper<se? 3. How do we aaract and retain the kinds of learners likely to become (adap<ve) experts to careers in teaching? 4. Is two years enough to make an impact on the future development of teacher candidates? 5. How will adop<ng a focus on the development of adap<ve exper<se impact those involved (the instructors and field supervisors and others) in teacher prepara<on? 6. Can colleges of educa<on become communi<es that support the development of exper<se? Hatano, G., & Inagaki, K. (1986). Two courses of exper9se. In H. Stevenson, H. Azuma & K. Hakuta (Eds.), Child development and educa7on in Japan (pp. 263‐272). Freeman & Co. Hoffman, R. R. (1998). How can exper9se be defined? Implica9ons of research from cogni9ve psychology. In R. Williams, W. Faulkner, & J. Fleck (Eds.), Exploring exper7se: issues and perspec7ves. New York: Macmillan. Hammerness, K., Darling‐Hammond, L., Bransford, J, Berliner, D., Cochran‐Smith, M, McDonald, M. & Zeichner, K. (2005). How teachers learn and develop. In, L. Darling‐Hammond & J. Bransford, Eds. Preparing teachers for a changing world: what teachers should learn and be able to do. Jossey‐Bass. Lajoie, S. P. (2003). Tradi9ons and trajectories for studies of exper9se. Educa7onal Researcher, 32, 8, 21‐25. Welker, R. (1991). Exper9se and the Teacher as Expert: Rethinking a Ques9onable Metaphor. American Educa7onal Research Journal, 28, 1, 19‐35. 6