The Effect of Ski Resorts on Population Dynamics

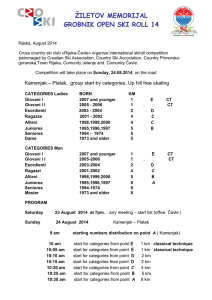

advertisement