Talent Pressures and the Aging Workforce: Responsive Action Steps for the

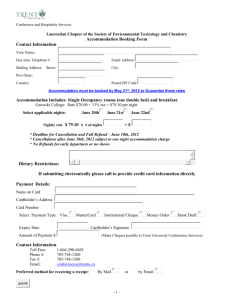

advertisement