NICHES: Nearshore Indicators for Clarity, Habitat and Ecological Sustainability

advertisement

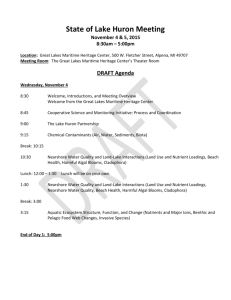

NICHES: Nearshore Indicators for Clarity, Habitat and Ecological Sustainability Proposal target theme: water quality subtheme: nearshore-shoreline ecology, processes, and stressors Dr. Sudeep Chandra Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Science University of Nevada- Reno 1000 Valley Road/ MS 186 Reno, Nevada 89512 Phone: 775-784-6221 FAX: 775-784-4530 Email: sudeep@cabnr.unr.edu Dr. Craig E. Williamson Department of Zoology 212 Pearson Hall Miami University Oxford, Ohio USA 45056 Phone: 513-529-3180 FAX: 513-529-6900 Email: willia85@muohio.edu Dr. James T. Oris Department of Zoology 212 Pearson Hall Miami University Oxford, Ohio USA 45056 Phone: 513-529-3194 FAX: 513-529-6900 Email: orisjt@muohio.edu Dr. Geoff Schladow Tahoe Environmental Research Center University of California- Davis Davis, California 95617 Phone: 775-881-7560 FAX: 775-832-1673 Email: gschladow@ucdavis.edu Grants contact person Ms. Petra Bartella University of Nevada- Reno Office of Sponsored Projects/MS 325 Reno, NV 89557 Phone: 775-784-4011 FAX: 775-784-6680 Email: petrab@unr.edu Total funding requested- $250,000 Total value of in-kind and financial contributions- $0 Justification statement Water clarity, water quality, and ecosystem integrity of Lake Tahoe are threatened by multiple stressors. The nearshore area is of critical importance since it is influenced by anthropogenic disturbances, is the primary interface with the general public, and supports native fish spawning and production. Recently agencies have taken a strong interest in managing the nearshore fishery due to increased distribution of nonnative plant (e.g. water milfoil, curly leaf pondweed) and vertebrate species (largemouth bass and bluegill), potential decline of native fish density, and decrease in spawning habitat (Kamerath et al. 2007, Metz and Harold 2004, Thiede 1997). The Tahoe Regional Planning Agency does have a threshold for nearshore fishes based on habitat. This threshold was recently found to be in non attainment (Threshold Evaluation Report) which stimulated the process of evaluating and developing new metrics to assess the nearshore fishery (Chandra 2007). In this study, we will develop a suite of metrics that will assess the short, mid, and long-term changes to the nearshore fishery. In particular the goals are to determine if traditional indicators commonly used to assess impacts in other ecosystems can be used to determine mid- and shortterm changes. The use of these indicators (density, growth, body condition) requires a comparison with information collected 15-40 years ago. We will also conduct experiments and field sampling to explore the development of a set of novel indicators that can be used to measure change on a short-term basis. These indicators (ultra violet light and trophic niche) are based on direct measurements of feeding behavior and survival of native versus nonnative fish due to changes in nearshore clarity. We believe a combination of metrics will allow managers to select which indicators are needed to monitor changes to the nearshore fishery. Background and statement of problem Lake Tahoe and existing nearshore fisheries indicators. Lake Tahoe is a deep, ultra-oligotrophic, subalpine lake located in the Sierra Nevada of California and Nevada, USA. It is known for its cobalt blue waters, which it owes to its small watershed area to large lake volume. Within the last 40 years, scientists have documented a steady decline in lake clarity and increase in primary production (Jassby et al. 1996, Goldman 2000). A combination of factors play a role in the decrease in clarity including the introduction of fine, inorganic particles introduced from the watershed, resuspension of fine particles, and the settling time of particles to the lake bottom (Jassby et al. 1996, Swift et al. 2006). Despite the decline in clarity, the relatively high transparency still results in the deep penetration of ultraviolet (UV) light wavelengths with UVA radiation penetrating as deep as most visible wavelengths of light, while 10% of surface UVB wavelengths penetrate down to depths of 15 m (Williamson and Oris, unpublished data). Furthermore, nearshore-offshore transects measuring water transparency during the summer of 2006 indicate that nearshore habitats are much less UV transparent than offshore habitats (Fig. 1). As a result of the decline of Lake Tahoe’s water clarity and unregulated growth, lawmakers (state and federal) created the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency (TRPA). This agency oversees development within the basin and has initiated a process to adopt environmental quality thresholds and enforce ordinances to achieve the thresholds. These thresholds include standards to protect water quality, scenic view, nearshore fisheries, etc. and were created via the development of a regional plan. The latest evaluation suggests the only established threshold for nearshore fisheries (known as F1: Fisheries habitat) is in non attainment (Threshold Evaluation Report). While there has been an increase in littoral zone habitat, there has been an overall decrease in suitable spawning habitat for native species due to increased development and disturbance (Metz and Harold 2004). Simultaneously during the evaluation process, a second process called Pathway 2007 involving a fisheries and wildlife technical working group identified scientific and threshold gaps for Lake Tahoe’s fishery. Two major gaps for the nearshore fishery included determining the impacts of new nonnative fish invaders and the development of biological indicators for the littoral zone of the lake. Our preliminary work in recent years suggests that decreases in water transparency are likely to create a refuge that may increase the suitable spawning habitat for UV-sensitive invasive species (see below). Indicators and attributes for their development. Multiple methods are generally needed to monitor the health of complex ecosystems. (Soule 1985). When utilizing biological indicators as surrogates for stress, one approach creates multimetric indicators. This accounts for a variety of attributes in connection with the area under investigation. Each metric or attribute is equally weighted and contributes to an overall score, which signifies the “integrity” of the fish community at a give site. Theoretically, the metric(s) reflect the degree to which the local environmental conditions influence the fish community and depends on a relationship to reference sites determined a priori. One positive aspect is that it takes into account a variety of attributes that represent the fish community in a given site (Simon 1991). Furthermore, the approach can be separated to determine both short and long-term evaluations once a metric has been deemed appropriate for the system. Thus, the score for the metric should reflect the fish community response to relative degree of disturbance at a particular site. Disadvantages are that much effort is exerted to collected environmental information that may or may not correlate with the fish community (Reynoldson et al. 1997). Metrics are also often redundant and can overweigh the effect of a single measurable outcome. Thus, each metric needs careful evaluation to provide the appropriate resolution when determining impacts. Furthermore, metrics often have to be developed for specific ecosystems since there is often no consensus on the statistical correlation between drivers and metrics across ecosystems. When developing restoration/ monitoring endpoints and detecting environmental change it is important to consider components which influence the outcomes including: 1) goal/ expectations, 2) measures that can detect change, 3) variability in measures in time and space, and 4) scale of measurement for each metric (Minns et al. 1996). Furthermore, having baseline information, understanding tolerance levels of specific taxa, and understanding niche and life histories of organisms is critical (Hilty and Merenlender 2000). Fortunately, we do have limited historical baseline studies of the nearshore fishery of Lake Tahoe that can provide information on alterations to the nearshore fishery. Most of the information collected from Lake Tahoe, however, is basic fisheries information (see below). We propose to utilize historic data and traditional methods of assessment combined with the development of novel indicators that, together, can demonstrate changes in the nearshore fishery at both long-term and shorter time scales. Existing information on Tahoe’s nearshore fishery, data that can aid in indicator development. While most of the continuous, long-term research has focused on determining primary/secondary production, chemical, and physical measures in the pelagic zone of the lake (Goldman 2000, Jassby et al. 1996, Chandra et al. 2004), there have been a series of snapshot studies in the nearshore community which have measured basic fish life history, diet, density, composition, and growth information that can be used to determine mid to long term change in the nearshore (California Fish and Game unpublished data, Byron 1989, Beauchamp et al. 1994, Allen and Reuter, 1994). Prior research demonstrates that native fish and nonnative crayfish make seasonal migrations from the nearshore to the sublittoral part of the lake (Thiede, 1997). Densities of nearshore fishes increase during the summer, moving to the deeper part of the lake during the fall. Furthermore, gravel is a limiting factor in the littoral zone affecting the spawning ability of native fish (Beauchamp et al. 1994). As a result, littoral fish communities utilize natural or human constructed (e.g. piers or retaining walls) rocky substrates. Studies from the 1960’s showed that nearshore native fishes feed on benthic algae and invertebrate, nearshore pelagic zooplankton, and terrestrial food sources. The diet of dace, when measured by volume, indicates that benthic invertebrates contribute more than zooplankton to their energetics. Redside shiners feed on nearshore zooplankton and benthic invertebrates. Pelagic chubs historically fed on other fish and zooplankton while benthic chubs fed on fish and benthic invertebrates. Finally, native forage fish which live in the nearshore are thought to have declined 10 fold between the 1960’s and 1990’s (Thiede, 1997). However, different methods were used to determine this change, and we believe further exploration is warranted. Development of short and long-term indicators for the nearshore. This proposal will assess the utility of developing multiple metrics as nearshore fish indicators. Our overall objective is to develop metrics that determine long and short-term changes to the nearhore fisheries. A list of indicators used to traditionally assess change in ecosystem management along with the development of new novel indicators is presented (Table 1). Table 1. Metrics that will be evaluated during this study to determine short and long-term changes and metric development for the nearshore fishery. Metric/ Indicator Detection Scale Data comparison to existing data Density long-term Yes- 1960, 1990, this study Composition long-term Yes- 1960, 1990, this study Growth rate long-term Yes- 1960, this study Spawning habitat/ mid-term Yes- 1990, this study Recruitment potential Trophic niche long-term Yes- 1960, this study Ultra violet light short-term No- this study Traditional metrics Density, composition, body condition, and growth rate. These traditional indicators have been used to evaluate change in other lake ecosystems. They have been used successfully to determine anthropogenic influences across lake ecosystems, but with mixed success within large lake ecosystems. For example, body length has been used to document changes in kokanee salmon after the introduction of Mysid shrimp (Mysis relicta) in Lake Tahoe (Morgan 1978). Other studies have used age of maturity as a stress indicator (Trippel 1995) and monitored body condition and growth to determine impacts. Generally these studies emphasize alterations within or across ecosystems that have experience drastic impacts. At Lake Baikal, however native fish composition did not vary in reference versus highly impacted sites located near a pulp and paper mill (Kudelin 2006). Thus, if baseline information exists, there is some potential that basic fish information can be used to detect change due to anthropogenic influences. Spawning habitat. Previous research suggests that spawning habitat for native, nearshore fishes is limited in Lake Tahoe (Allen and Reuter 1994). Recent research suggests there may be a decline in spawning habitat, but two different methods were used to make this determination (Metz and Harrold 2004). Furthermore, while the substrate may be a limiting component of habitat, preliminary research by the PI’s suggest the tolerance of native versus nonnative species to UV light and thus oxidative damage may be important in lakes with increased clarity (see ultra violet light section below). Thus, UV light may be a strong controller of larval recruitment and production. Since spawning habitat is currently the only threshold developed as a nearshore indicator by TRPA and may limit recruitment of native fisheries evaluating the current distribution of spawning habitat is critical to determine if this metric can bed used to detect change over time. Novel metrics The variability associated with traditional metrics may not allow managers to determine where change has occurred or may occur within the nearshore habitat of Lake Tahoe. Furthermore, traditional metrics typically detect change in a retrospect and across ecosystems that exhibit substantial anthropogenic influences (e.g., severe cultural eutrophication, nonnative species introductions, etc.). Lake Tahoe has exhibited progressive eutrophication compared with other ecosystems. Thus there is a need to develop sensitive indicators that can detect and predict subtle changes over time. Trophic niche. The bioenergetics of an organism can determine the body condition, growth rate, and survival of an organism. Energy utilization is one component of fish bioenergetics thus, direct measures of fish diet over time and space can be used as a metric for potential growth and reproduction. In Lake Okeechobee, there are spatial differences in the diet of fish of similar species and size, indicating the importance of localized habitat for production (Fry et al. 1999). Lake Tahoe’s nearshore has undergoes seasonal changes in periphyton biomass (Hackley et al. 2004, Hackley et al. 2005, Hackley et al. 2006) that may be influence by local human, induce disturbances. Since research from other large lake ecosystems suggests “bottom up” production can determine nearshore fish production and composition (Yuma et al. 2006), it is likely that alterations to benthic and pelagic, nearshore production in Lake Tahoe influence diet and production of nearshore fishes. Ultraviolet light. Our unpublished data indicate that UVA radiation penetrates as deep into Lake Tahoe as most visible wavelengths of light, while 10% of surface UVB wavelengths penetrate down to depths of 15 m (Fig. 1). These high levels of UV radiation can cause significant biological damage to aquatic organisms living in the surface waters of the lake. However, native species are less threatened because either they are able to live and reproduce in the deeper, colder waters of the lake, or they are UV tolerant. Exotic species such as warm-water fish depend on warm, shallow, nearshore habitats for spawning. Since these species are less tolerant of the high UV conditions at Lake Tahoe, reductions in UV transparency may allow these exotic species to invade the lake. Our nearshore-offshore transects measuring water transparency during the summer of 2006 indicate that nearshore habitats are much less UV transparent than offshore habitats (Fig. 1). These shallow nearshore habitats also have the warmest temperatures in the lake. The combination of these higher water temperatures and lower UV transparency in nearshore habitats creates a refuge that may facilitate the invasion, establishment, and spread of exotic warm-water fish species. Our previous experiments in eastern lakes have demonstrated that UV transparency reduces the spawning success of warm-water fish in shallow waters (Williamson et al,. 1997; Huff et al., 2004; Olson et al., 2006). Lake Tahoe is much more transparent than these lakes. However, reductions in nearshore UV transparency may create a refuge for these warm-water fish to invade and persist in Lake Tahoe (Fig. 1). Data from nearhore-to-offshore UV profiling transects in Lake Tahoe demonstrate that shallow environments nearshore to some of the major inflows are far less UV transparent than offshore (Fig. 1) and that patterns of UV transparency change from month to month. This is important because nearshore habitat must be present during summer months that provides both the warm temperatures and low UV conditions that favor spawning by exotic species such as largemouth bass (Carlander 1977). Evidence from laboratory and field experiments indicates that there is a strong species-related difference in sensitivity to UV-induced oxidative stress in fish. For example, sunfish are significantly more sensitive to oxidative stress compared to minnows (Fig. 2) (Oris et al., 1990; McCloskey and Oris, 1991). Native and resident fish, including minnows and trout appear to be adapted to the high UV conditions at Lake Tahoe and are significantly less sensitive to UV-induced oxidative stress compared to nonnative species (Fig. 2). Extrapolating from comparisons of studies among species (Fig. 2), we expect that exotic centrarchid fish should be between 12 – 125 times more sensitive to UV-induced oxidative stress than native and resident Lake Tahoe fish. Thus we propose that this differential UV sensitivity can be used to develop a “UV Threshold” that can be attained to minimize susceptibility to exotic centrarchid fish species invasions in Lake Tahoe. UV transparency can also serve as an effective indicator of water clarity that is more sensitive to environmental change than conventional measures of visible wavelengths used to measure transparency or turbidity. We propose to develop a UV-based optical change index (OCI) that demonstrates greater sensitivity to changes in water quality compared to traditional measures (e.g., secchi readings). We applied this index to examine relative changes in water transparency to UV and visible light in Lake Tahoe from May to July, 2006, at several nearshore and offshore locations and within Emerald Bay. Water clarity changes in Emerald Bay from May to July were much more pronounced for UV than for visible light (Fig. 3). Changes for UVB and UVA radiation were seven and three times greater than changes in visible light respectively (Fig. 3). We also measured UV and visible transparency along two transects in the southern and northern portions of Lake Tahoe in May and July to examine changes in nearshore versus offshore water clarity. From May to July transparency across all wavelengths increased in the nearshore systems, but decreased in the offshore sites (Fig. 4). Again the OCI demonstrated that UV transparency was consistently more sensitive to changes in water quality than visible light transparency (Fig. 4). This greater sensitivity of UV to changes in water quality are related to the greater absorption of UV by both particulate and dissolved substances in the UV versus visible wavelength ranges (Fig. 5). Therefore, when inputs of particulates and dissolved substances change, UV is affected more than visible wavelengths. By measuring UV, more information about changing inputs of particulates and dissolved substances can be gathered. Goals and objectives The objective of this proposal is two fold: 1) provide a contemporary evaluation of the nearshore fishery and 2) evaluate a variety of traditional indicators that may be used to determine long-term change, and 3) develop novel metrics to detect shorter term change to the nearshore habitat of Lake Tahoe. Specifically, the goals are to determine whether o long-term changes in the nearshore fishery can be created using traditional indicators such as density, composition, body condition, and growth rate; o mid-term changes can be determined by determining changes in spawning habitat, thus the potential for larval fish production; & o two novel thresholds (trophic niche and ultra violet light attenuation) can be utilized to determine shortterm changes in the nearshore fishery Locations of research and methods We will conduct this study at a minimum of 10 locations in the nearshore of Lake Tahoe: Tahoe keys, Baldwin Beach, Sugar Pine point, Obexier’s marina, Sunnyside, 64 acre beach, Lake Forest, Patton beach, King’s Beach, Secret Harbor. These are 10 of 22 locations that were evaluated during the shorezone studies of the early 1990’s (Allen and Reuter 1994). The metric, detection scale (short or long-term change), and information on previous data collection for each metric is presented (Table 1). Traditional indicators Density, composition, body condition, and growth rate. The basic information collected in snap shot studies since the 1960’s allows for the direct comparison with these parameters. In order to determine if there have been alterations over the long term using these parameters we will measure the density, composition, body condition for each species, and growth rate from each location. Samples will be collected at monthly intervals from Jan to Dec at each location. Following the methods used in Beauchamp et al. (1994) we will conduct overnight minnow trap set at each location from 1, 3, 10, 20, 30, 40 meters). Body condition will determined using the Fulton’s condition factor (Bolger and Connolly 1989). Previous population level growth rate information was collected using scales. We will determine age using scales and opercula for fish from each location. Comparisons using Student t-test adjusted for sample size will be used at each location to compared condition indices over time for each species. Spawning habitat/ recruitment potential. We will reassess the spawning substrate available at each location made during the early 1990’s shorezone study (Allen and Reuter 1994). The sites comprise a variety of open sand to cobble and gravel substrates. Each site will be snorkeled during the day and night with observations for spawning behavior or presence of eggs (Allen and Reuter 1994). Random substrate grabs will be taken from each site and identified for particle size and composition using the United States Geological Survey, Laboratory Theory and Methods (Guy 1969). Surveys will be begin in April and continue through the first week of August since spawning significantly decreases by July (Allen and Reuter 1994). Since spawning was found to occur at all disturbance levels (swimming, boating, etc.) measured in the early 1990’s, we will not evaluate disturbance levels and focus on substrate type. Additionally since recent research suggests the deep and nearshore waters of Lake Tahoe are warming (Coats et al. 2006, Chandra and Allen unpublished data) and since UV light is believed to impacts potential recruitment we will measure temperate and UV light at each location. Temperature will be measured using ibutton continuous data loggers and UV methods are describes below. Development of novel metrics Trophic niche. We will determine if diet shifts have occurred in native, nearshore fishes over time (1872, 1912, 1960 and present). Specifically, we will quantify the utilization of benthic versus pelagic production over time for each species. Utilizing similar methods that have been used for previous isotope studies at Lake Tahoe (Vander Zanden et al. 2003, Chandra 2003), we will measure carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes from fish at each location at the end of summer. Isotopic δ13C will be used to determine the flow of organic matter through food webs (Gu et al. 1994; Vander Zanden et al. 1999). The minimal enrichment (±.47 ‰) from lower to high trophic levels allows for the differentiation of littoral and pelagic primary production sources (Hecky and Hesslein 1995; Vander Zanden and Rasmussen 2001). With predictable enrichment (between 3-4 ‰) biotic trophic position will be determined using isotopic δ15N (Minagawa and Wada 1984; Vander Zanden and Rasmussen 2001). Historical samples will be obtained from museum collections as done previously for Lake Tahoe (Vander Zanden et al. 2003, Chandra 2003). Sample procedures as outlined in Chandra et al. (2005) will be followed. The trophic niche of each species will be determined by measuring their pelagic carbon reliance and feeding level. The dependence of individual fish on pelagic energy will be determined by the following equation: % Pelagic = [(δ13Cfish- δ13Clittoral)/ (δ13Cpelagic- δ13Clittoral)] * 100, 13 where δ C fish is the individual value for fish. The littoral endpoint, δ13Clittoral (the mean of littoral amphipod, crayfish, mayfly, snail, and fingernail clam samples), represents the benthic primary production signal. The pelagic endpoint, δ13Cpelagic (mean of all zooplankton), represents the pelagic primary production signal. Fish trophic position is estimated from fish δ15N values. Individual fish signatures will be corrected for baseline variation using invertebrate primary consumer δ15N similar to Vander Zanden and Rasmussen (1999). Trophic position is calculated as TP= ((δ 15N fish- δ 15Nbaseline)/3.4) + 2, where 3.4 is the trophic level enrichment factor (Minagawa and Wada 1984, Vander Zanden and Rasmussen 2001). A pooled baseline linear regression equation from previous Tahoe studies (Vander Zanden et al. 2003) will be used since no significant difference occurred between years. UV light. Our approach involves two major components: field surveys to characterize the UV and temperature conditions in the nearshore environment, and laboratory and field experiments to determine UV exposure thresholds of both exotic (largemouth bass) and native (redsides and/or dace) fish under both artificial and natural solar UV conditions. For the survey work we will use a BIC submersible UV-Visible radiometer (Biospherical Instruments, Inc.) to collect data on both UV and visible light to monitor changes in water clarity in Lake Tahoe. By using both UV and visible transparency we will be able to separate the relative contributions of particulate and dissolved fractions (Fig. 5). Particle size analysis will be conducted in situ using a LISST 200 submersible particle size analyzer. Additionally, a Seabird SBE25 profiler will provide standard limnological properties in-situ. These include water temperature, DO concentration, PAR attenuation, light transmission and optical backscatter. A bbe Fluoroprobe will provide profiles of chlorophyll for individual algal functional groups. Thermal, optical, and water quality measurements will be made along transects at five locations around the lake including three areas of concern for turbidity increases (south shore near Upper Truckee River inlet, Tahoe City, and Incline Village), one control site where turbidity is less of a problem (Sand Harbor), and Emerald Bay, a site where impact is potentially high due to high levels of public use. At each nearshore site a transect will be run from the shore, optical and temperature profiles taken, and surface water samples collected every 0.1 – 0.25 km offshore to a depth of 25 m, the maximum depth at which temperatures are likely to reach the bass spawning limit of 15oC. We will sample twice during the period of potential maximal spawning of warm-water fish when temperatures exceed 15oC (June - September). Integrated UV exposure over a period of one week during each sampling period will be estimated at each nearshore site by incubating DNA dosimeters at depth intervals of 2 m from the surface to a maximum depth of 25 m. Dr. David Mitchell at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX) will be responsible for conducting DNA damage analyses. Water quality analysis of surface water samples will include dissolved organic carbon (DOC), chlorophyll, and particulates according to the standard techniques used in our laboratory (Morris et al. 1995, Williamson, et al. 1996). Multiple regression analysis will be used to relate these water quality variables to UV and visible transparency measurements (Morris et al. 1995, Williamson et al. 1996) To test UV sensitivity thresholds of native and exotic fish, we propose to use a combination of laboratory and outdoor experiments with Lake Tahoe native species (speckled dace and Lahontan redsides) and an exotic species (largemouth bass) following methods adapted from Williamson et al. (2001). Laboratory tests will be conducted in solar-simulating chambers (phototrons) that achieve approximately 90% of natural sunlight dosages. Exposures will be conducted with native species collected from Lake Tahoe (cf. Miller et al. 2003) and largemouth bass. Laboratory water, with minimal DOC, chlorophyll, and suspended materials will be used in these tests. Individual juvenile fish will be placed into each of 40 individual dishes of 30ml in the chamber and exposed to simulated sunlight for 12 hours. Fish will be removed from the chamber and survival will be recorded over the next 5 days. Five levels of simulated sunlight will be used to establish dose response relationship for each fish species (Williamson et al., 2001). Field exposures will be conducted in outdoor phototrons similar to those used by Oris et al. (1998), Miller et al. (2003), and Roberts (2005). Organisms will be exposed to natural sunlight for 7 hours during mid-summer at TERC. Water from a low, medium, and high turbidity site will be used to examine the mitigating effects of natural water constituents on UV tolerance thresholds. Forty individual fish will be tested for each water type, and mortality will be assessed after a single day of exposure and followed for 5 days post exposure. DNA dosimeters will be utilized and irradiance measurements will be taken during all exposures to determine the biologically-weighted dose of UV during experiments. Nonlinear regression will be used to establish biologicallyweighted dose response relationships (Williamson et al., 2001) for all species in laboratory experiments and will be validated using the outdoor exposures. These relationships will be used in combination with the field survey data to determine predicted UV thresholds for the prevention of exotic warm-water species invasion in nearshore waters of Lake Tahoe. Development of a UV Threshold for Lake Tahoe The data from field surveys and from laboratory and outdoor UV exposures will be used to determine a UV Attainment Threshold (UVT) for Lake Tahoe that can be easily measured and used to manage nearshore waters in an effort to minimize invasion and establishment of warm-water exotic fish species. We propose to use a target value of the diffuse attenuation coefficient for UVB (Kd320) as this threshold. The Kd320 is measured by conducting a UV profile as described above and calculating the slope of the line derived by plotting the log of UV intensity at 320nm versus depth (cf. “UVB” in Fig. 1) and has units of reciprocal meters (1/m). The process for the development of the UVT will proceed in a stepwise fashion as follows (Fig. 6). (1) Using temperature profiles from transects, we will determine the maximum depth in the lake that can be used as spawning habitat for largemouth bass. (2) Data from field UV profiles will be correlated with levels of DNA damage measured by dosimeters. There is a strong, linear relationship between these two measurements (cf. Fig.. 1), and a model will be developed that predicts UVB doses from rates of DNA damage. (3) A dose-response relationship between UV-induced mortality in bass and in native species and rates of DNA damage by dosimeters placed into the phototrons, will be determined. Dose-response relationships will be compared between bass and native species and the relative potencies of UV dose will be determined (Oris and Bailer, 1997). Based on a typical approach for determining efficacy of a pesticide (Ritz et al, 2006) we will select a rate of DNA damage that causes a high amount of mortality (e.g., >90%) in bass, but a low amount of mortality in native species (e.g., <10%). We refer to this rate as the Effective Dose of DNA Damage (ED DNA). (4) The predictive relationship determined in Step 2 will then be used to establish an Effective Dose of UVB (EDUV) that will achieve the target amount of bass mortality. (5) The UVT can then be calculated by solving for Kd320 in the equation that describes light penetration in water: ln(Iz) = ln(Io) – Kd320Z where: (equation 1) Z = depth (m) Iz = UV320 intensity at depth of “z” (Jm-2) Io = UV320 intensity at surface (depth = 0 m) (Jm-2) Kd320 = diffuse attenuation coefficient for UV320 (1/m) Substituting appropriate parameters, equation 1 can be expressed as: ln(EDUV) = ln(Io) – UVTZ(spawn) (equation 2) EDUV = effective dose of UV selected to target bass mortality (Jm-2) (Step 4) Io = as above for equation 1 (directly measured) Z(spawn) = maximum depth of bass spawning habitat (m) (Step 1) UVT = UV Attainment Threshold (1/m) Rearranging equation 2, we can solve for the UVT: where: UVT = [ln(Io) – ln(EDUV)]/Z(spawn) (equation 3) The UVT will be useful regardless of what disturbances may be present that change quality and clarity of the nearshore water column. These disturbances range from algal productivity, to turbidity, to invasive macrophytes, to changes in water temperature resulting from local runoff or from long-term climate change. Strategy for engaging with managers We will engage managers by presenting quarterly updates in either an oral or written format to agencies managing fisheries issues within the basin (TRPA, Nevada Division of Wildlife, California Fish and Game, US Forest Service, US Fish and Wildlife Service). We will also present at fisheries technical working group meetings to gain input on our findings and outputs. Deliverables/products Thresholds indicators are of urgent need for management agencies attempting to manage and restore native fishes within Lake Tahoe. The primary deliverable product will be the determination of which methodologies are needed to develop short, mid, and long-term metrics for evaluating the nearshore fishery. In addition, we will provide quarterly progress reports, a preliminary report (end of first year), and a final report (end of project). As part of this project we also expect to make presentations at annual scientific meetings (e.g. ASLO, ESA, SETAC, regional meetings), submit manuscript(s) for publication, and make public presentations of data as requested. Schedule of Events/Reporting and Deliverables June 2008- May 2009: Preparation and initiation of field collections at 10 locations. June- September 2008: UV field experiments: field collection of natives, laboratory & field experiments with natives and non-natives and UV-temperature surveys. October 2008- April 2009: DNA damage and data analysis. Further lab experiments with bass as needed. Traditional metric lab processing (aging, isotope analysis, body condition). Preliminary report delivery. May- December 2009: Lab processing, data analysis January- April 2010: Data analysis and final report delivery Budget justification. We request funding for two years to support this project. Dr. Sudeep Chandra and Geoff Schladow will be responsible for evaluating the basic life history indicators (density, composition, body condition, growth condition), compiling existing information for comparisons and measurement of general lake properties and particle size distribution. Dr. Sudeep Chandra will also be responsible for developing the trophic niche indicator. Drs. Craig Williamson and James. T. Oris will be responsible for conducting the development of the ultraviolet light indicator. They will design and implement the experiment and field collections for this section. All PI’s will meet with managers to inform them of the progress of this research. References Beauchamp, DA, WA Wurtsbaugh, BC Allen, P Budy, R Richards, and J Reuter. 1991. Lake Tahoe fish community structure investigation: phase III report. University of California, Davis, Institute of Ecology Publication 38. Bolger T and PL Connolly. 1989. The selection of suitable indices for the measurement and analysis of fish condition. J Fish Biol 34:171–82. Byron, ER, BC Allen, W Wurtsbaugh, and K Kuzis. 1989. Final report: littoral structure and its effects on the fish community of Lake Tahoe. Institute of Ecology, Division of Environmental Studies, University of California, Davis. Carlander, KD. 1977. Handbook of Freshwater Fishery Biology Volume 2, Life History Data on Centrarchid Fishes of the United States and Canada. Ames, Iowa, The Iowa State University Press. Chandra, S. 2007. Determination of the methods needs to examine the health of the nearshore fishery in Lake Tahoe. Tahoe Regional Planning Agency. Chandra S, Vander Zanden MJ, Heyvaert AC, Allen BC, Goldman CR. 2005. The effects of cultural eutrophication on the energetics of lake benthos. Limnology and Oceanography. 50: 168-1376. Coats, R, J. Perez-Losada, et al. 2006. The warming of Lake Tahoe. Climatic Change 76: 121-148. Goldman, C. R. 2000. Four decades of change in two subalpine lakes. Verh. Internat. Verein. Limnol. 27: 7-26. Guy, HP. 1969. Laboratory theory and methods for sediment analysis: U.S. Geological Survey Techniques of Water Resources Investigations, book 5. Fry, B, PL Mumford, F Tam, DD Fox, GL Warren, KE Havens, and AD Steinman. 1999. Trophic position and individual feeding histories of fish from Lake Okeechobee, Florida. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 56: 590-600. Gu, B, DM Schell and V Alexander. 1994. Stable carbon and nitrogen isotopic analysis of the plankton food web in a subarctic lake. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 51: 1338-1344. Hackley, SH, BC Allen, DA Hunter and JE Reuter. 2004. Lake Tahoe Water Quality Investigations: 2000-2003. Tahoe Research Group, John Muir Institute for the Environment, University of California, Davis. 122 p. Hackley, SH, BC Allen, DA Hunter and JE Reuter. 2005. Lake Tahoe Water Quality Investigations: July 1, 2003June 30, 2005. Tahoe Environmental Research Center, John Muir Institute for the Environment, University of California, Davis. 69p. Hackley, SH, BC Allen, DA Hunter and JE Reuter. 2006. Lake Tahoe Water Quality Investigations: July 1, 2005June 30, 2006. Tahoe Environmental Research Center, John Muir Institute for the Environment, University of California, Davis. 64p.. Hecky, RE and RH. Hesslein. 1995. Contributions of benthic algae to lake food webs as revealed by stable isotope analysis. Journal of the North American Benthological Society. 14: 631-653. Hilty, J and A Merenlender. 2000. Faunal indicator taxa selection for monitoring ecosystem health. Biological Conservation. 92: 185-197. Huff, D. DG. Grad, et al. 2004. Environmental constraints on spawning depth of yellow perch: The roles of low temperatures and high solar ultraviolet radiation. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 133: 718726. Jassby, D. 2006 Modeling, Measurement and Microscopy - Characterizing the Particles of Lake Tahoe. MS Thesis, UC Davis. Jassby, AD, JE Reuter, and CR Goldman. 1996. Determining long-term water quality in the presence of climate variability: Lake Tahoe (USA). Canadian Journal of Fisheries Sciences. 60: 1452-1461. Kamerath, M, S Chandra, and BC Allen. 2007 (In press). The distribution and abundance of warmwater invaders in Lake Tahoe. Aquatic Invasions. Kudelin, VM. 2006. Survey of fish inhabiting the littoral zone of southern Lake Baikal. Hydrobiologia. 568(S): 57– 61. McCloskey and JT Oris. 1991. Effect of water temperature and dissolved oxygen on the photo-induced toxicity of anthracene to bluegill sunfish. Aquatic Toxicology 21:145-156. Metz, J and M.Harold. 2004. Using IKONOS imagery to map near-shore substrates, fish habitats, and pier structures in Lake Tahoe, CA/NV. Miller G, C Hoonhout, E Sufka, S Carroll, V Edirveerasingam, B Allen, J Reuter, J Oris, M Lico.2003. Environmental Assessment of the Impacts of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAH) in Lake Tahoe and Lake Donner: A Final Report to the California Sate Water Resources Control Board. UNR, U. C. Davis, Miami University (Ohio), USGS. Minns, CK, JRM Kelso, and RG Randall. 1996. Canadian Journal of Fisheries Sciences 53: 403–414. Minagawa, M and E Wada. 1984. Stepwise enrichment of n-15 along food-chains - further evidence and the relation between delta-n-15 and animal age. Geochimica Et Cosmochimica Acta. 48: 1135-1140. Morgan, MD, ST Threlkeld and CR Goldman. 1978. Impact of the introduction of kokanee (Oncorhynchus nerka) and opossum shrimp (Mysis relicta) on a subalpine lake. Journal of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. 35: 1572-1579. Morris, D. P., H. Zagarese, et al. (1995). "The attenuation of solar UV radiation in lakes and the role of dissolved organic carbon." Limnology and Oceanography 40: 1381-1391. Miller G., C. Hoonhout, E. Sufka, S. Carroll, V. Edirveerasingam, B. Allen, R. Reuter, J. Oris, M. Lico.2003. Environmental Assessment of the Impacts of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAH) in Lake Tahoe and Lake Donner: A Final Report to the California Sate Water Resources Control Board. UNR, U. C. Davis, Miami University (Ohio), USGS. Olson, M. H., M. R. Colip, et al. (2006). "Quantifying ultraviolet radiation mortality risk in bluegill larvae: Effects of nest location." Ecological Applications 16(1): 328-338. Oris, JT, AT Hall, and JD Tylka. 1990. Humic acids reduce the photo-induced toxicity of anthracene to fish and daphnia. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 9(5): 575-583. Oris, JT, and AJ Bailer. 1997. Equivalence of concentration-response relationships in aquatic toxicology studies: Testing and implications for potency estimation. Environ. Toxicol. Chem.: 16: 2204-2209. Oris, J, B Allen, et al. 1998. Toxicity of ambient levels of motorized watercraft emissions to fish and zooplankton in Lake Tahoe, CA/NV. SETAC-Europe, 8th annual meeting abstracts. Ritz, C, N Cedergreen, et al. 2006. Relative potency in nonsimilar dose-response curves. Weed Sci. 54(3): 407-412. Roberts, A. (2005). Gene Expression in fish as a first-tier indicator of contaminant exposure in aquatic ecosystems. Ph.D. Dissertation, Miami University, Oxford, OH. Reynoldson, TB, RH Norris, VH Resh, KE Day, DM Rosenberg. 1997. The reference condition: a comparison of multimetric and multivariate approaches to assess water quality impairment using benthic macroinvertebrates. Journal of the North American Benthological Society. 16: 833-852. Simon, TP. 1991. Development of ecoregion expectations for the index of biotic integrity. I. Central corn belt plain. US Environmental protection agency, Region 5. Chicago, Ill. Soule, ME. 1985. Biodiversity indicators in California: taking nature’s temperature. California Agriculture. 49: 4044. Swift, TJ, J Perez-Losada, SG Schladow, JE Reuter, AD Jassby and CR Goldman. 2006. A mechanistic clarity model of lake waters: Linking suspended matter characteristics to clarity. Aquatic Sciences 68, 1-15. Thiede, GP. 1997. Impact of lake trout predation on prey populations in lake tahoe: A bioenergetics assessment. Thesis. Type. Utah State University. Threshold Evaluation Report. 2006. Chapter 6: Fisheries. Tahoe Regional Planning Agency. Trippel, EA. 1995. Age at maturity as a stress indicator. Bioscience. 759-771. Sarakinos, HC, ML Johnson and MJ Vander Zanden. 2002. A synthesis of tissue-preservation effects on carbon and nitrogen stable isotope signatures. Canadian Journal of Zoology. 80: 381-387. Vander Zanden, MJ, S Chandra, BC Allen, JE Reuter and CR Goldman. 2003. Historical food web structure of Lake Tahoe (CA-NV) and the restoration of native fish communities. Ecosystems. Vander Zanden, MJ and JB Rasmussen. 1999. Primary consumer delta13c and delta15n and the trophic position of aquatic consumers. Ecology. 80: 1395-1404. Vander Zanden, MJ and JB Rasmussen. 2001. Variation in delta n-15 and delta c-13 trophic fractionation: Implications for aquatic food web studies. Limnology and Oceanography. 46: 2061-2066. Williamson, CE, RS Stemberger, et al. 1996. Ultraviolet radiation in North American lakes: attenuation estimates from DOC measurements and implications for plankton communities. Limnology and Oceanography 41: 1024-1034. Williamson, CE, SL Metzgar, et al. 1997. Solar ultraviolet radiation and the spawning habitat of yellow perch, Perca flavescens. Ecological Applications 7: 1017-1023. Williamson, CE., P. Neale, et al. 2001. Beneficial and detrimental effects of UV on aquatic organisms: Implications of spectral variation. Ecological Applications. 11: 1843-185. Yuma, M, OA Timoshkin, NG Melnik, IV Khanaev & A Ambali. 2006. Biodiversity and food chains on the littoral bottoms of Lakes Baikal, Biwa, Malawi and Tanganyika: working hypotheses. Hydrobiologia. 568: 95-99. Figures Tahoe Inshore Site #4 May 3, 2006 Irradiance as % of deck cell 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 10 100 Irradiance as % of deck cell 100 0 2 4 UVB UVA Visible Depth (m) Depth (m) 10 Tahoe Offshore Site #22 May 4, 2006 6 8 10 12 14 UVB 16 UVA 18 Visible 20 Figure 1. Vertical profiles of UVB (320 nm), UVA (380 nm) and visible (400–700 nm) radiation nearshore and offshore in Lake Tahoe in early May 2006. Note the much greater water transparency to both UV and visible light near the center of the lake. The most damaging wavelengths of UV (320 nm) do not penetrate as deeply nearshore as offshore, creating a potential nearshore UV refuge for exotic species to spawn and spread. UV Sensitivity Comparison 7 Days Exposure @ Lake Tahoe (Oris outdoor studies in: Miller et al., 2003) 30 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 Juvenile bluegill (800 mg) are nearly 5x more sensitive to UV-induced oxidative stress compared to larval fathead minnows (2 mg) . Percent Mortality Anthracene (!g/L) Oxidative Stress Comparison Fathead Minnow vs. Bluegill Sunfish 25 20 15 10 5 0 FHM BGS (Oris et al., 1990) (McC loskey & Oris, 1991) DAC RBT LRS FHM Figure 2. UV sensitivity of native and resident Lake Tahoe fish species compared to nonnative and invasive species. The left panel is a comparison sensitivity to UV-induced oxidative stress between larval fathead minnows (FHM; standard test species) and juvenile bluegill sunfish (BGS), an invasive centrachid in Tahoe. The right panel shows a comparison of UV tolerance among juvenile Lahontan Speckled Dace (DAC), larval Rainbow Trout (RBT), and juvenile Lahontan Redsides (LRS) relative to larval fathead minnows (FHM). Optical Change Index 0.40 Emerald Bay 0.35 0.30 0.25 0.20 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00 UVB UVA Visible Figure 3. Change in optical clarity ( ln (KdMay/KdJuly), where Kd = diffuse attenuation coefficient at each wavelength) in Emerald Bay from May to July 2006 demonstrating the much greater sensitivity of shorter wavelength UVB (320 nm) and UVA (380 nm) to changes in water transparency when compared to conventional visible light measurements. This suggests that monitoring of UV wavelengths can provide a more sensitive indicator of shifts in nearshore water clarity throughout the year while simultaneously providing information about the levels of damaging UV that may inhibit spawning of exotic species of warm-water fish such as largemouth bass. Optical Change Index 1.50 North Transect 1.25 1.00 0.75 0.50 0.25 0.00 -0.25 UVB UVB UVA UVA Visible Visible -0.50 -0.75 -1.00 Nearshore Offshore Optical Change Index 1.50 South Transect 1.25 1.00 0.75 0.50 0.25 0.00 UVB UVB UVA -0.25 UVA Visible Visible -0.50 -0.75 -1.00 Nearshore Offshore Figure 4. Change in optical clarity (ln (KdMay/KdJuly), where Kd = diffuse attenuation coefficient at each wavelength) in both nearshore and offshore habitats along a transect on the western shore (between inlets of Blackwood and Ward Creeks) and southern shore (offshore of inlet of Upper Truckee River) in Lake Tahoe from May to July 2006. Note again the greater sensitivity of shorter wavelength UVB (320 nm) and UVA (380 nm) to changes in water transparency when compared to conventional visible light measurements. The positive index values represent increases in water transparency nearshore from May to July, while the negative index values show that offshore water transparency decreased from May to July. These data suggest that monitoring of UV wavelengths is a more sensitive indicator of shifts in offshore as well as nearshore water clarity throughout the year. -1 Absorbance (m ) 3.0 2.5 dissolved 2.0 particulate 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 290 400 510 620 Wavelength (nm) Figure 5. Absorbance by particulate and dissolved fractions of lake water separated by a GFF filter. Note that both particulate and dissolved absorbance is higher in the UV wavelength range (< 400 nm) but that dissolved absorbance increases much more rapidly than particulate absorbance at shorter wavelengths. This suggests that changes in UV and visible absorbance can be used to separate out the relative contributions of dissolved and particulate compounds to water clarity both inshore and offshore. Step 1. Determine Max Spawn Depth Step 2. Relate DNA Damage to Measured UVB Intensity Temp v. Depth Profiles UV-320 v. DNA Damage ln(UV320 Intensity) Temperature (C) 30 20 10 Z (spawn ) 0 0 10 20 Depth 30 1 0 0 1 ln(Relative DNA Damage) Step 3. Determine relative UV Dose -Mortality Relationships & Calculate Effective Dose for Bass Mortality Proportion DNA Damage v. Mortality Dose -Response Bass Native sp. 1.0 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0.0 ED DNA 0 3 4 Relative DNA Damage Step 4. Determine Effective Water Column Intensity of UVB for Bass Step 5. Calculate UV Attainment Threshold for UVB ln(UV320 Intensity) Setting ED UV Value 1 UVT = ED UV [ln(Io) - ln(ED uv )] Z(spawn) 0 ED DNA ln(Relative DNA Damage) 0 1 Figure 6. Steps taken in the determination of a UV Attainment Threshold (UVT).