On

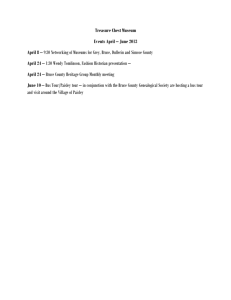

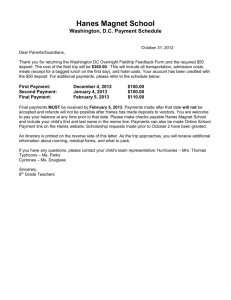

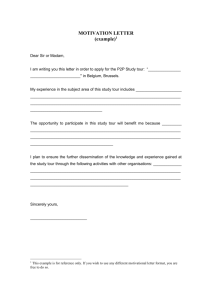

advertisement