499 by

advertisement

F.N EX1- LORn TORY STUDY OF CREli. TIVITY -

IN -

T~CHING

STUDIES

I~J

FIFTH GfiliDE SOCIAL

A F DELle SCHOOL SYSTEM

ID 499

by

JEANNETTE GhLL

1-I.DVISER - DR. RUTH HOCHSTETLER

BALL STATE UNIVERSITY

MUNCIE, INDInN.n

l-'lliY 6, 1968

/'

-

The author wishes to thank Dr. Ruth Hochstetler

and Dr. Fay Clardy, Jr. for their aid in the

compilation and the evaluation of data in the

following study.

C~&~ter

I

11

III

~age

Introduction sod

nevi8w of

~ollec

ti,)n

of

t~e

~roLleffi.

nesearct

;:.nd iVa lua liou

;:)uillr:..ctry

~nd

t1-~~endix

biLllographi .

..

1

o

of Da ta .

.............

IV

v

nel~teQ

St~tement

•

.

.

• 1)

• • 1S

Conclusions .

25

. • . 33

•

•

j'l

CHbFTER I

Introduction and Statement of the Problem

Creative teaching has as its task the guidance and the

release of creative fotential.

n teacher is cre8tive in the

sense ttat he aevelors an etmosrhere that is

creativity of others

an

ideas are accerted.

at~osrhere

in which every child's

It is not assumed, ho~ever, thet

teachers can be divided into two groufs

ffiust also carefully

deter~ine

~ferate for a time in

c~n

~

the creative ond

Nor is it assumed that any cne te3cher will

teach creatively 911 the time.

teacher

to the

In 8ther words, the crertive teacher

fGnctions as a catalyst. l

the uncreative.

favora~le

8

It is felt

t~9t

s teacher

the roints at which he

routine way.2

be 0escribed as valuing

~ust

The more crestive

diverge~t

thinkine m0re

th2n copvergent thinking and an open-ended system more than a

closed syste~.3

The Ioint has been made that the more

crestive teccher also hDs a sense of security in uncertainty

and

8

tolerance for amt'igulty.4

FinGlly, a cre~tive teach~r

has a subjective attitude toward the subject matter and is

oriented to movement from the known to the

effifhasizing the form2tion of new ideas.5

un~nown,

thus

2

The importance af determining the extent to which

creative teaching Cbn be described rests on the value of

creativity itself.

This value is reflected by an abundant

consensus on the need for creativity in education.

This

consensus may be due to the fact that society is facing new

needs. 6

In the attempt to face new needs comes a warning

from an educational newsletter:

In today's world cre~tivity is not just a nice

thing to have. It is a grave necessity.

Imitating the past is not good enough; only

the creativ8 society will survive.7

Emphasis on creativity as

in~ovation

Gnd invention in our

schools then is necessary because "we c9nrwt predict what a

person will need tc know in the 21st century as

~ell

as in

the next third of this century,,8 and because it is recognized

that "our very survival defends upon the quality of the

cre2.tive imagination of our next generation."9

Recent recognition of the proposed need for creativity

in education is illustrated by the contrast of past Bnd

present attitudes loward creativity and its encauraeement.

In the past, the general impression has been that the successful development of creative ability should concern itself

with persons of unusual artistic, musical, or literary endawmanto

In the past, creativity has also teen regarded as a

spontaneous act with no consciously directed means for its

development.

However, cre~tivity is now regarded 33 a goal

of education. le In the categcry of recent developments ~re

s~ecific

admonishments as to the present state of education

3

since the recognition of the need for cre&tivlty.

~dmonishment

Cne such

begins --

We need to take a fresh, inventive, crestive

look into the curricula of schools and colleges.

It is clear that they sre geared to lIinput,·! but

not to "out;,utrl. ;,~e still emph",size .Ithe

dnplication of knowledge," but do Ilttle vdth

creative explicatio!1., im:[:licaUon, 2nd ap~lication.

We need more learning for doing. 11

This study is concerned with a possible discrepancy

between fact and opinion in the area of creative teaching.

Opinion, for the pllrpose of thls study, :i.s rerresented by the

educational philosophies of many schoal systems which extol

the virtues of cre£tivity 3nd stress the importance of

creativity in

F3ct is approached through an

teachin~.

attempt to measure the

particular system.

c~eutive

Fsct,

practices of teachers in

asks

rephr~sed,

&

"To whet extent

do elerrentG:ry teacr.ers atternrt to teach creatively:'·

This

q ues t ion, then, forrrs the core

5

r)f

the :r:robler; of th i s

The problem itself required an

sization of

&

irn~ediste

definition of cre3tivity.

can be defined in

IT20Y

either a

product, rersooality,

~rocess,

condition. 12

tucy .

synthe-

Cre0tivitv.

. , which

ways, is usually defined in terms of

~r

envi~on~ental

For the :r:urrcses of this study, however,

emphasis is pl&ced on crec:tiv:ity as

environmental cond1tion.

~hether

approaches which are conducive to

~r

2.

process and as 8.n

not a teacher employs

creztivi~y

Dnd whether or

not she establishes a climEte or environment whjch aids this

process are points Jf

e~rh2sis

for this study.

Neming the

point of view taken is, however, not particularly definitive.

In order to be more definite, a number of basic

assumptions were compiled:

1.

It is assumed that creativity deals with

newness in the sense of either a person~l

rediscovery of what has already been discovered Q!: the }:roduction of something

entirely new.13 This implies both the

transmission and the transformation of

kno't/ledge .14· -

2.

Such concepts as curiosity, imagination,

discovery, innovation, and invention are

indicative of creativjty, but cannot be

equated with it.15 Creativity enco~passes

them all; it is not li~ited to a single

function. 16

3.

Creetivity can not be copied. 17

4.

Creativity refers to what is going on

within the individual - his own way of

thinkin~, feeling, and doing.

As he

devises ways of expressing ideas or

feelings which to his knowledge have

originated ~ithin his own thinking and are

not forced by the environment, he is

develcping through the process of

creativity. The creative process then is

Q

assumed to be esse~tial to self-realization. 1u

5.

It is assumed that every individu&l possesses

the ability to be cre~tive. This ability,

however, varies with individuals in regard

to strength and/or area in ~hich they are

ca~able of expressing it.lS

6.

It is also assumed that creativity can not

be taught, but can be released snd guided.

No one ferson can tell another person how to

be c:r"?E. ti ve becb use the es sence lies 't none's

own Jnsjght, underst&ndings, ~nd feelings.,2Q

7.

The purpose of cre&tive education, it is

assumed then, is to guide creative processes

which must be guid.ed (encouraged, nurtllred,

allowed) .21

5

Li~it~ticns

The

st~dy

has certain

of the Study

limit~tions.

The decision was

made, fjrst of all, not to attemrt to measure evidence of

creative teaching in a]l aress of the curriculum.

Such a

task would be an imfossible one to perform with any degree of

accuracy or validity.

The most feasible apfroach, it was

felt, would be to concentrate on obtaining a measure for a

number of teachers in one sfecific area of the curriculum.

The area decided upon was social studies.

The choice \lias

largely due to the nature of social studies, since it is

"an integration 01 subject matter and conce.r:t formulation

which calls for a bE>lance and synthesis betwel2n social and

academic learning and between the immediate and the remote."22

Such a n a ree. should frovide a tr.f Ie oPI-iortuni ty for' creB ti ve

teaching. 23 The desire to heve subjects as alike as possible without reference to individual differences in attitude

and personality led to the choice of teachers in a specific

grade level in a public school system.

including children's

res~onses

~ith

the intention of

to questions concerning

practices in the classroom, grade level five was chosen.

Fifth grade children were thought to be capable of unders tanding and answering any q ues tion i.neluded

j

n the interview,

if each question were carefully analyzed as to .ocabulary

level and possible ambiguity.

chosen for the sarre

re~son,

Grade six could hsve been

but was not, due to a ;reference

for and interest in the lower erade by the auttor, who was

also responsible for interviewing.

CHuFTER II

Review of Relcted Research

Over the past few ye5rs there have been many studies

of creativity.

All of these have been concerned with the

nature of the concept of creativity, the identification of

creative individuals, or some specific classroom applications

of creativity.

The data reported reflect a

s~ecific

instructiona 1 setting, or the findings are of a theoretica 1

rather than a practical nature.

Few of these publications

report practices relative to creativity which are representative of teaching in elementary schools.

There are,

however, seven studies reported in the past ten years which

appear to be pertinent to the determination of creative

teaching.

Of these seven stUdies three were found to hove a

direct relationship to the problem in this study.

The most

recent of the three, itA Survey of Eeliefs and Practices

Relative to Creativity," by William C. :""olf ,Jr. was published

in March, 1964 in the Journal of Educational Research.

The

purpose of this study was, first of all, to find out how

classroom teachers viewed the concept of creativity.

Wolf's

next concern was that of making a survey of learning experiences employed by teachers under the guise of creativity.

7

This study did not include the categorization of classroom

teachers as creative, less creative, or uncreative, nor

was the study interested in a particular area of the curriculum.

In a six state area, teachers were asked by a

mailed questionnaire, "what do you ttink 'creativity' is?"

and "w'ihat do you do in your classroom which you consider to

be creativeri".

study:

ficcording to the data collected in the

almost half of the responding teachers conceived of

crea ti vi ty as a persona 1 characteristic; one-fourth rela ted

it to a product or end; while one-fifth identified the

concept as a process.

The data,

ho~ever,

crepancy in tbe teachers' statements.

revealed a dis-

Manifestations of

creativity in the classroom did not seem consistent with

the teachers' view of creativity.

Inconsistencies of this

nature were blamed on vaguely conceived efforts to make

provision for "a nebulous concept ll in the school curriculum.

The data also reported a widespread acceptance of creativity

which Wolfe regarded as remarkable because the relationship

between creativity and elementary education is so very

recent.

Froffi the data, Wolfe constructed a response pattern

for the mythical "typical teacher".

This teacher -

1)

conceived of crea ti vi ty as e. persona 1 cha rac teris tic,

2)

described creative learning experiences which pervade the

entire elementary scheol curriculum, and

these experiences to

ex~edite

instruction in the classroom.

3) employed

specifjc learning and/or

Wolfe concluded that:

8

Creative

utilized

teachers

relstive

learning experiences are extensively

in today's elementary school; many

adhere to similar beliefs and practices

t04-creativity consistently in the

classroorr,"~

The next oldest of the three studies, "... Guide to

trinciples of Creutivity-in-Teaching with Suggestions for

Use in Elementery Social Studies" by Edwc:.rd F. stone was

completed in 1961.

Stone compiled, from a review of

literature, fifteen principles of creativity in teaching.

Using these principles he built into his stJdy seven illustrations of creative exreriences in social studies which he

obtained from the puLlic schools of Great Neck, New York.

The seven teachers, K-6, who provided the illustrations

were evaluated prior to the study

creative peDple.

3S

professional and

These were judged according to criteria

established by the investigation and supported by a jury of

school personnel.

Stone concluded by means of the illus-

trations that one could show a valid relationship to the

general principles through their successful application in

actual clbssroom situations.

The degree of relationship,

however, was not mentioned.

Stone then wrote a guide for

elementary teachers which he hoped would stimulate teachers

to work more creatively in the classroom.

The guide also

included:

• • .8 sumc~tion of the theory of the creative

process translated into a fur.ctionally suggestive

record of certain experiences that have been

offered children with successful results. 2 5

The purr-ose of the third study is apparent from its

Superi0r in Dem8nstr:ting

Cre~tjveness

in Teachi nf l'.

1j)7 issue of tho. Journ:?l of Educations] SesearC'h.

conclusions have teen thc most

B:nd found

stu~ies.

P':'nn's

of the threc

c~rnrr~hensive

closs relcti:nship between

9

The

hi~h

mean

scores jn cr9stiveness and general superi')rity in te?cbjnq.

He concluded that creativeness is essential ss

fector to

supe~ior

teaching

s~c('ess

~nd

~

contributing

that it is rro-

portiG~~lly lacking with teachers of inferjor 8biljty.26

Bond 21so

c~me

to the conclusion that:

It is highly suggestive th~t teachers lacking

strength in rl&nnlng and teaching creatively

take refuge in working with supplies snd

equip~ent and in testing pu[ils cn whst they

-~esum~blv hpve lprrno~

c.-!.

_ .... - )n

.. . . t~eir

L J.",,v~w~... d~/·

J:~";'

""

-,,-,,,,

'"

-'"

.

~

.j". '-"

The limited findjngs of

8

fourth study, one by Cnrol

F. Mershsll, h,:s m":!'je it riifficult t:: eql1Ete the stt1 dy,

!'Classroom Ferce:r,:ti':Ds of Hif!hly Cre,3tive

~e=chers

Howev~r,

it is of significance to the

i' ::.--es Gnt s tlJdy b9c? use :)f the re 13 ti oDs':.i

res;onses of

hi~h1y

found thEt

crc~tive

hi~hly

guided il

N(~

1t!E.S

f0und cetween

t~acters.

crentive teachers tended to

Ilfo11:J1,.;s directions,"

attec.I-t

r

and less creative

sugg8st~?d

•

Less Cre::::tive

in the E]e;rrentc::.--y 8('\;.ocl,'1 with the thr,ee studtes

glready described.

M~::.--sh911

::~.:1d

r.'Jade

"sits jn seat", 2nd "te::.:.C'h2r

in tLe study, hov:ever, to

exr:Ltin how either the "hie;hly cre<::tive"

O~

1'1ess c-restjve"

10

teachers were chosen or categorized. 28

The three remaining studies contain findiQgs which

msy be regarded

crea ti vely.

l~.

&S

pertinent considerations for teaching

Studies by three authors, !,'rank E. May, Janet

Gilbert, and DonE.ld J. Eadley, produced findings on the

relationship between intelligence and creativity while they

were investieating relbted problems.

The data used in

Gilbert's study, suprorted the previous findings of Getzels,

and Torrance who found that intelligence tests

Jac~son,

were not satisfactory instruments for identifying creative

stUdents.

Gilbert also hypothesized that on standardized

measures of achievement, the creative student

w~uld

do as

well or better than less creative studeGts, but that he

would not fbir as well on teacher marks. 2 9

was supp,orted.

This hypothesis

fI.ay's findings from a study of the crestive

thinking of seventh graaers agreed with those of Gilbert •

.hay found tha t wi th popul,,- tions thE. t are fairly homogeneous

with respect to intelligence, I.Q. scores are probably poor

predictors of creative-thinking ability.

between

I.~.

Correlations

scores snd creative thinking scores in the

study ranged between .08 and .30 with most of the correlations

approaching zero. 30

Hadley, in a study of the relationship

between creativity and anxiety, discovered additional

support for the findings of both Hay and Gilbert.

In his

study, hadley found that a group of children who are low in

anxiety and high in intelligence, were not similarly high

in creativity.

According to the data those with very low

11

anxiety exhibit a moderate amount of creativity; those with

a slightly higher amount of anxiety exhibit the highest

amount of creativity; and those with increasingly higher

anxiety exhibit increasingly less creativity.

Hadley also

found strong evidence that:

matter how much anxiety a child may feel,

the introduction of some common behaviors of

teachers which research indicates induce

anxiety will curtail creative production.3 l

~o

A

major accomplishment of publications on creativity

has been the labeling of sources of discouragement to

creativity.

is said to

One such source of discouragement to creativity

~e

the school itself.

Data gathered by Spindler,

Getzels and Jackson, Torrance, Colem&n and Henry suggest

that the stUdent is being dominated by the school and instead of having his creativity nourished, his thinking,

feeling and reacting are restricted. In other words, he is

being stifled. 32 Two factors encountered in the school are

said to be responsible for the stifling.

is the work-play dichotomy.

The first factor

Day states that teachers

suppose that there should be no playing around in work and

so they do not give children many opportunities to learn

creatively because lIchildren enjoy creative experiences and

their I-leasure makes teachers uneasy. "33

The second factor

is that of sanctions against questioning and exploration.

According to the data gathered, teachers do recognize that

students need to ask questions and make inquiries about

their environment, however, children who do so are lIoften

12

brutally squelched" in order to "put the curious child in

his place. 1I34

ticcording to Shumsky, it is the intent of

ffiOSt teachers to "present a stereotyped, sugar-coated

portrai t and to avoid struggle and controversy. "35

Shumsky

indicates tb3t there &.re three types of teachers -

the

reretitive teacher, the main-idea teacher, and the creative

teacher. 36

Niel poses this question, "Do we really have to

stand by and watch the training of mediocrity'i"3?

8

itself.

second source of discouragement is said to be society,

A

major obstacle is society's success orientation.

The point is made that individuals are prepared by military

and civilian education only for success, not for coping

with frustration and failure.

The inhibiting effect of this

tendency "is seen again anQ again in the individual testing

of chi ldren on ta sks of crea ti ve thinking. 1138

.tl.nother

factor, although still dealing with success, has to do with

the current pressures of society on schools to maintain

high academic standards.

barron indicates that the response

by school people to this pressure

h~s

taken the form of

increased pressures on children for rote memorization of

facts. 3S

hnother factor within society which exerts pressure

on the student is his peer group.

Feer groups undoubtedly

value conformity, and equate divergency with abnormality.

In doing so, they exert relentless pressure on one another

to rid themselves of any divergent characteristics. 40

one of the most significant personal characteristics of

Yet

13

especially creative children seems to be the courage to

step beyond the established bounds.

Thus they have to fight

the peer group and often do so without teacher sup[ort. 41

I t would seem, then, the t the tea cher who a t tempts to teach

creatively must do battle with society in

child's peer

grou~,

~eneral,

the

and in some cases the school, itself,

and the teachers therein.

In the opposite vein, points of encouragement have

also teen shown by research.

Lists have been compiled

describing what iliUSt te done by a teacher to increase the

crea ti vi ty in his teaching.

These are not s tand-pb t

formula s, nor are they reco;r,mend 2. tions for the use of any

certain materials.

Particular materials cannot be recommended

because it has been concluded that too little is yet known

about the effects of various instructional media on

creativity.42

The creative teacher appr0aches ~nowledge

with the question me as a person r( 1143

"'what does the subject matt.er meCin to

Taylor summarizes the present state of

affairs by saying:

lt may be more effective at the present stage

to develop materials designed to remove hindrances

and to untrain for nO~4creativity than to directly

train for creativity.

In addition, Torrance has emphasized the importance of

learning how to rewCird creative behavior if children are to

think creatively. 45

hnd, according to Dale, the ultimate aim

of education should be to try to make stUdents alike enough

so that they can communicate with each other, yet different

enaUEh so th:t they ~ill h~vc something worth co~~unic3tin~.~6

The issue, then, has been eVG1usted.

h3ve been identified . .> rhil=so[hy of need

Su~~estions

exreriences.

enc~urape

have been

ih?t

ma~c

to imrlement or

s92~inEly

remfins to be

the thoughtflll rursuit

~f

The bErriers

t~s

rr~duce

~~d

belief in the rhilcs0;hy of need

~lready

formul&te~.

creative

cc~o~rlished

the rrccess

instill, most certainly to test,

teen

to

~nd

ultimately to

is to

~erhaps

u~h01d

fcrmul&tsd.

CHAfTER III

Collection snd Bvaluation of Data

lhe processes used in collecting Gnd evaluating data

in the present study were very simple.

They can be described

in order of the topics of selection, populstion,

instrumentatioh, and evaluation of responses, which immediately follow.

Selection:

A

letter was sent to each of the fifty-five

fifth grade teachers in the hetropolitan Schools of Muncie,

Indiana.

p~rpose

of the study and asked for their cooperation. (See

~nclosed

card.

This letter contained an explanation of the

s;;c~~iv)

in each letter was a stamped, self-addressed reply

On the reply card the receiver was to indicate his

willingness to

p~rticipate.

If the teacher

~ished

to

participate, he consented to a ten-minute interview.

The

teacher selected three of his students for individual interviews of approximately equal length.

The letter requested

that the teacher select a student who, in his estiffiation,

was a "good student", another whom he felt liked social

studies, Bnd a third student who was a "poor st1.Adent" in

his estiffiation.

The students were chosen in this manner in

order to obtain a cross-section of the students in each

individual classroom.

If a teacher returned a positive

16

reply he was

so that

c0nt~cted

2

time

~nd

for the

~&te

interviews could to set.

[cful&tion:

t~e

Fy

of the interviewing period which

8nd

extended frem J&l1.usry 23, lS6c through F'ebr:'1c.ry ,26,1<;62,

fcrty teachers

interviewed.

:JDe hunr1red forty students hed baen

:~nd

Due to a

d~screrancy

in the format of the

children's interview in the first three sets, where a set

consisted of one teacher und three of his students, these

sets were discounted in the evaluation of the

The

st~dy.

sacple used in this study was thus reduced to 37 teachers

and III students for Iurrcses of evslu9tion.

re~resented

the Muncie

This

s6~ple

t\o.'enty of the twenty-two elerr:entary schools in

Schools.

~etrop:lit~n

Interviews

conducted with each teacher

~ere

student in the school

Such

buildin~.

~reas

as

Q

~nd

each

teachers'

leunge, the nurse's cliniC, or the music room were used fur

interviewing.

nny room where it was ,elt that tje child

would receive a

utilized.

~jni~um

of distr&cting influence was

The length of an

jntervi~w

veried from seven to

twelve rJinutes.

Of the III students, 60 were boys

Of the "]7 Hqood students

The

of the

nu~ber

',

r~cr st~dents

of girls

excee~ed

c::: tegory Df the "g ood s t uden t

InstrumentEtion:

The

51 were girls.

12 "'"ere boys :.nc 25 1J.Jcre

s~bject grou~,

of the f:vorite

fs~~le;

l

e~d

24 were

m~le

s~d

l~

~irls;

were

24 were boys sod 13 were girls.

the nurrber of boys only in tte

I' .

instr~~ent

used with teoohsrs was a

17

one-pege interview guide.

with the children.

n

two-pdge interview outline was used

The items were a compilbtion of those

suggested for use by various authors, since no single available instrument seemed to be valid for use with children in

the measurement of their perception of classroom practices

and atmosphere.

following topics:

Items on the teacher-interview included the

(1) method used in teaching socia 1

studies; (2) resp:mse of students to preser,tation of subject

metter; (3) neture and number of social studies projects for

student participation during the school year; (4) emrloyment

of bnd success with the problem-solving a[proach; (5)

wi 11ingness to a t tempt "unusua 1 tI a cti vi ties

,~ bout

which they

n.ight feel "insecure" in terms of outcome; (6) excursions

or field trips taken by the class during the year; (7) role

playing and dralliatization used in social studies; (8) use

of study guides by the tea cher; ond (9) rea c tion to a chi Id

who is "individualistic and non-conforming".

Items on the

student-interview were related to the following topics:

(1)

freedom to disagree; (2) freedom to handle materials in the

classroom; (3) student-centered or teecher-centered classroom; (4) strength of impression of ,,;hat is Leing studied;

(5) response to the presentbtion of subject matter; (6)

group work; (7) view of society; (5) divergent thinking; and

(9) construction in the classroom.

Evaluation of Responses:

In the evaluation of each

questionnbire tte raw score assigned to each teacher was

determined by an equivalent to the number of positive responses he made on nine of eleven items included in the

18

teacher's

~

interviE~.

mean of 4.5.

A

fossible range

Two items included in the

no variance in teacher response.

student

~as

~as

from 0 to 9

intervie~

~ith

produced

The score assigned to each

also determined by an equivalent to the number

of positive responses on nine 3eparate items.

A

}earson

~roduct-~oment

(r)

~ith

.05 level of con-

fidence

w~s

then used to determine three separate correlations:

(1) the

ra~

scores of the IIgood studentll with the

of the teacher; (2) the

student 11

~i th

ra~

ra~

score

score of the IIfavorite subject

the raw score of the teacher; (3) the raw

score of tte "poor studentll wi til the raw score of the teacher.

Individual items were examined for significant response

patterns.

Finally, a composite score

~as

obtained for each

teacher by adding the teacher's raw score to one-third of

the scores for each set of three students interviewed per

teacher.

CR.,iTER IV

The

~0~;ut3tion

f~r

of the Fe:rscn lr)

e~ch

~f

the

three? e-rours of stucierts ':,1 th thei!' tes chen; !'eve:: ~ed the

the 1'","Jd students

II

,',ere

c~T'rel['

t:::d

'di

!' C' ',;

S (' 0 !' e s

:) b t ,<:,i rl e d fer t h 0 t esc be!' s;

ra~

scores

ott~incd

TWG~ty-six

c e rl t

~

methods in teaching

or thirty

the unit, in

me~sure

scci~~

~er

te3c~ing

teacher

~ll

.05

r

no ton e, 'b 1) t

st~~jes.

•

sccisl studies.

i~rressi2n

the

level.

2.

C 'J mt

si~ty-twJ

i rn t i:m

0

~O~

'f'

The rem:injng eleven

un 2n itc!::'

CD>S

~ent,

in 1f/h.ich

rer cent, of the

to

llse~

t~~~rj

scc13l

6:id detect s.n

i~dlvjd~,jls

"corr,rl.stely 3bsorb:::d il in their soci2l studies

th,~

~IJ h e !1

three coefficients

of student 3ttitude

strrcs;here of Ilsusrension" or

hO\o.'ever, fel t

.3 3

cent, rerorted the use :)f one method,

studies fourteen, Gr thirty-eight :re'!"

three, cr

seeros

r9'/J

of the thirty-seven te::ch2!'s, cr seventy

r or: 0 r t -2 d t he us e :) f

te~~hers,

(J) r

fGr the tS2chers.

found to he significsGt 2t the

~ere

th the

',vc!'e

worl~.

thjrty-seve~

t8~chers,

t their stUdents were !'r",rely or never

20

rr~je~ts,

yielded twe r ty-thra9

r~sit1ve

six t Y- bl D r e:' c e n t 0 f the t c : =1,

;:0

nrl f 0 1.1 r t e 8 n,

eight rer cent, neg:tJve reSrcns2s.

T'CS't-~/u4~

"nsc>'

........

_,

t't,onty-three

.,-,...

.....

,r,

n(·'C1~

''''"''".

_.::,.""

t; V""

-

reSr2ns2s,

tr~ j l' t

Y-

In the esse of the

\~n""

~.--.

__

D:~

~r ~b:ut

1I.1i....,p

_.1._

(':"'_.

2h

'-"u·t

__

-....- v

t,·'pntyw_

four ;.er cs!"t :)i' the tilirty-seven tesC''1ers rc;rcrt2c errrl::yi..'lg

the

rr~t18T

selving

~rrr~Gch

nIl inci:Lc3ted3 fC21ing ci'

,<

in the

they

fe~t

whi~h

they

c0nsj~ered

0"

unusual

activities in

~ut

~jtte~rted

o?:' t!iirty-t\·;r:; :;'er r:-ent c:!" t":e

Twanty-three

re~

OT'

::-n 2ctivity Hbich they

te:~.cheT's

hc'.d

cent

o~

sixty-t~D

the

~er

t?~ch2rs

hs~

fourteen or

thirty-ei~ht

Twelve

rr?~1e2YCUrsi:ns

twenty-fjve

not dune so.

cent oi the t:cchers

the use of role-playin e or dr::u(,tization in

re~~ining

~hich

Tb? rerraining

rem~injng

the

cbcut

the Dutcome of 2ctivitips in their classroom.

or sixty-eight

cl~ssrccm.

seventy-three rer cent of the tcochers

rero!'ted th::-,t they hE,d n:-:t

~b8Ut

att2~rtjnE

insecure in terms of the outcome.

twenty-seven

studias

"l'l'lcderate de€,ree of success."

f0r cent of the teachers rerorted

the c13ssroom

scci~l

SOCi:~ll

rer~rted

st')diesj

reI' cent, hOwever,

re,t:orte-::l th:Jt tilCY did not em:rloy either c;ctlv:lty in the

nrcc of

scci~l

studies.

Eleven or thjrty reI' cent cf the

21

teschers rerorted

stu~y

~uides;

th~t

ttey

;

the r c rr j

On the f')11o\;dnz

t3s~hers'

cent cf the t8?chers

;21'"

::.

n i n g t r: n::; r s; r 1" :) v: i rr co tel y t'.'! e n t y - s eve n

j

tern"

hI8'1tY-:Gl)1" :Jr six-ty-fiv·:; per cent

0

teschers r2icrted that

t~ey

"f0el thrc3 toned 11 by suche:: chi 11.

8,...

orde~

In

c~

s",:"e;estions fr:::m the study

cr thirty-five per cent of th

I'::!islikc 'l

extensive use

sixt82n ::r forty-thrc3

1)sin~

g 11 ide s i I

~~je

f'er

~

tesc~er

scc;re on s11 iterr.s he ShOll1d:

t:J have 3n entirely rositjve

(2) use E c0mbinsticn

methods in te:.chirr, scci::.,l studies;

~c)

ce

~bl'?

of

to i!2tect

En Co,tr::::sphere of Ilsus;ensicn on the r2rt :)f stlJde'1ts :)r ':Jf

indivjdu~ls

being currrletely sbsorbsd in tteir soc1?1

stllci'?s work "t tirres;

(c) use

~r')jccts

in his su::::i::l

in the cl3ssro:)m ". . Uch he cunsiderad unlls'.1s1 :;,!1d :::b8 1Jt

he

m~y

tri);:"s

feel insecure in terms of

C.S

~

le.s.rnir.r: ::2tivity;

dram~tiz3tion

( f"

~

)

US,?

field

\2) em:;:lcy role rL:iying or

in the s8cial studies cl?ss

consirjst'ed Eppr:Jpris te; (h)

study gvides;

outc:)~e;

',\)~lich

~c(:d

E r.d uc;e

~h2n

they yere

sugg~sti

C'ns fr..:.m

(i) hsve S ;;ositive attitude to\oJsrd the

,Iinc:!i vidu:; J j,stic S.!"ld n'")D-c:;nforming ii child.

StuClent Intervi'?\I.':

NinetV-.!"line stude!1ts or eightY-!1i!1.3 per

cent of the students whc were interviewed gave

f~ll

22

of ttejr ;r2soDt saci:l studies

des~ri~t1c~s

students

e~2ve~

studying in

W8r~

L i gh t

11

~r

0

rer~ent

soci~l

f' t h'" hi C 1 v e

\,'3 r

stu~i~s

enthusissm fer 30cisl

not

~ble

twelve

to rec311 whst they

: t the time of the

e " roc I' S t

Cn the

13020 student".

~ere

wor~;

1)

d e "1 t s ", t h:r e e

j~terview.

1'.' e:r e

item c::ncert'1irg the student I s

se~~:)!'"l(:1

sixty-seven or sixty

stu~ies,

per~ent

of the; stlJdents SE:td th:'t th::y (lid '!C't "excited" ?"h::::ut "Jhst

th2Y studjed in sc;cisl sturlies, the r'2sairdnC' forty ;.ercent

or forty-four' students ssid they h:::.d ilnever" been exci ted

about

soci~l

studies durjng this schoel

y~ar.

Itew

nU!'!lbers three ena f::::ur on the jnterview were :{llesti::-ns used

divereently.

ene

~C'rce~t,

Cn the third item, fifty-fivs

m~de

res:~nses

rerce~~

of the

ver~ert

rather then

c()n~ernin§':

land

~r

~1ver~e~t

w~ich

t~irteen

were indjcstive :f

thinkinq.

E

On thn

f!"icndshir in

or

indicate~

thj~ty-t~::

n

item

f::rei?n

see~ed

m~re

reSrOr'lSC's

nG~r}y

c~nverg~nt

t~tnkjna.

Thirty-six

rercent of the students resrnnded cfftrm?tjv21y

during this schoal yesr.

eight rercent

f~urth

[crcent of the students

ninety-seven st 1Jdents,

which

fifty-

resrans2s indicative of con-

~~de

the est2blishrr10 :1t cf

f8u~teen

resI0nses

stu~e~ts

~h1ch

stu~ents,

m~de

The rem3injng seventy-five or

neE~tive

resronses.

~inety-seven

or

si~ty-

23

eighty-seven ;crccnt

felt free t:

r~r0rtedly

clessmstes ever tcrics under

discussi~n

'I'h-== Y"2mainJng fuurt'?en stllcsnts

tete;l rilj

feel

n:~t

fifty-one rercent

c frc2d:rr1.

s~ch

rerorte~

in social

stu~ies.

h:elve }:'2T'Cent

CY'

with

dis~grec

~f

the

Fifty-seven students or

thst they felt free to cxrlore

end exreriment with things in the c12ssrcom; however, ftfty-

students or forty-nine percent, did not feel this

f~ur

freed(~m.

F'orty-fcur students or

they did work j n s;rall

~roup

g1"~ur:

Sixty-seven

~ork.

,9.1

out forty

I='cr(~ent

s tn sod s 1 st'Jci as

~tudents

c;

nc

s8id

enj:;yed

or sixty rercent,

ssi~

that

Cn the finsl item in t ho student

they dicj enjoy grcup work.

u~

intervj_2'.t!, seventy-six students or

percent viewed their classroom

8S

,TrI~rC'ximstely

sivty-nine

being student-centered.

The

remaining thirty-fjve students, thjrty-one rercent jndicated

th2t they

In

thou~ht

their

clsssr~om

wss t83cher-centered.

to the jnfarmeti0n

~dditi~n

~ained

en each of the

nine items, the data rev821ed that students Ierceived some

indlvidusls

5S

"helrful"

Dnd

lIencourc~ing'l.

~.tcut

thirty-one

rercent of the studects attrjbuted tho role of the most

helpful rers8n to

less thon

!1!10

one d

~ne

3S

E

frienrl; sixty-eight rercent to the teacher;

rorcent to "myself"; ::n:d one [crcent cJnsinered

most helrfu1.

In

th~'?

lstter cDse, thEt cf the

mcst encour:ging flg:ure, forty rercent of tr:e students

attributed this rc18 to the tee,cher;

twenty-thrcE~

percent to

s friend; 2nd thirty-seven r er'.;ent ccns i nered "myself" or

" no one'l

2S

most enccursgin€,.

24

Gomtosite Scores:

Seventeen of the thirty-seven teachers

or forty-six percent received composite scores above the

mean of 9.8 while twenty of the thirty-seven teachers or

fifty-four percent, received a composite score telow the

mean.

the distribution of the scores indicated one very

creative teacher, nine moderately creative teaCllers, twelve

less cre&tive teachers, and fifteen who used very little

creativity in the teaching of social studies as evidenced

by their composite score.

No teacher was found to be

cOffipletely lacking in crebtivity since the lowest composite

score was

5.67.

Summary 2nd Conclusions

lhe

of this study has been to investigate the

pur~ose

question -

Do eleITientary teachers attempt to teach

creatively?

If so, to what extent?

The area in which the

investigation was carried out was fifth-grade social

studies.

Indivicuol interviews were conducted with thirty-

seven fifth grade teachers of the

~uncie

hetropolitan

Schools and with three students from each of their classrooms.

reachers were asked to choose one student whom they

perceived

E.S

a I'good student l ' , one student who, it was felt

I1liked socisl stu.dies ll , and one whom they feltwc;s a t1poor

student. I'

.-.t the end of the interviewing period an

eva lua tion wa s

n~C.

de of the res:t:onses to the q ues tionna ires

from thirty-seven teachers end one hundred eleven students.

C&lcul~tion

of the Pearson (r) revsbled correlations between

the teacher scores and each group of students which were

significant at the

.05 level.

On the item

an~lysis

of the

teacher interviews, four of nine practices regarded as

indicstive of creativity in teaching were not employed by

a majority of the teachers.

Twenty-three of the thirty-

seven teachers felt that they could not detect an atmosphere

of "suspension l ' indicative of who were completely absorbed

in their social

st~dies

work.

Twenty-eight of the thirty-

seven teachers admittedly did not use the problem solving

ar:proach in the social studies class.

thirty-seven teachers

h~d

Twenty-seven of the

not attempted anything

~hich

they

considered unusual or in which they were unsure of the

outcome.

fwenty-five of the thirty-seven teachers, for

whatever reason, have not made an excursion with their class

this year.

The following conclusions seem to be justifiable from

the do. ta obtained in this study:

(a) the classroom a tmo-

sphere in social studies in a large numler of cases could

be termed "inadeq ua te "; (t) there is an infreq uen t use of

problem solving in social studies, the use of which is

advocated for other subject areas; (c) practices of

teac~ers

lean toward the conventional and teachers seem reluctant

to attempt anything which they might consider unusual.

Teachers seemingly desire to feel secure in their teaching

and are reluctant to try methods about which they might

feel insecure or unsure; (d) a majority of the teachers in

this study felt that the effort of making arrangements for

a

field trip are greater than the advantages of an excursion.

It was concluded from the item analysis of the stUdent

interviews that according to the students interviewed:

Co.)

Students do not receive a great deal of encouragement to

apply divergent thinking to social stUdies problems; (b) Des pi te the ta ct tba t s tuderlts enj oy g roup-work in socia I

studies, group work is not employed by teachers; (c)

27

Industrial arts, which involves construction activities,

is a minimal portion of the social studies program.

Do teachers

element~ry

att6m~t

to teach creatively in the

classroom, as indicated by their teaching in

social studies(

It would seem

'~:ise

to conclude from the

scores the t the problem can not be answered "yes" or "no".

No teacher was found to be completely lacking in the atility

to teach creatively.

~ll

of the teachers with the exception

of one had at least two areas, however, in which definite

could be made in order to improve thejr standing on

ch~nge

a creBtivity scale.

lhe act of teaching creatively, then,

c& n be put on a continuum from "highly crea ti ve" to

extremely low in creativity, or "uncreative", with most

teaching falling somewhere in between.

The greatest

number of teachers were found slightly below the mean.

Suggestions for Further Research

~

number of interesting questions and points for

future exploration were encountered durins the collection

of data for the study.

1.

~hat

Some of these were as follows:

is the influence of race and socia-economic

level on individual creativity?

Is one race or

socio-economic level more likely to engage in

creative activities than another race or socioeconomi cleve 1 c(

2.

What can be done to emphasize the creative process

instead of only the end product so that stUdents

28

will recei\e a more accurate and direct picture

of the tot&l

3.

~rocess?

What are the challenges in creativity?

How much

emphasis should be placed on determining the

instructional media that would be most effective

in putting across the process?

4.

Will students tend to be more flexible, imaginative,

and creative if they are exposed to a wider

variety of instructional materials?

5.

Is an open system necessarily conducive to creative

thinkicg?

~hat

effect does an open system have on

divergent thinking?

6.

How can professional

peo~le

adapt the processes

to increase divergent thinkicg to the elementary

cIa s sroom~i

7.

How successful are creativity workshops in improving a te&cher's ability to teach creatively

as measured by increase in number of creative

practices before and after the workshop?

8.

To what extent do the findings of stUdies with

essentially the sallie format, but different items

on interviews or questionnaires, differ from one

another'?

For example, if the questionnaires in the

present study consisted only of the very direct

twenty ideas compiled by Torrance, would the

conclusions be the same as were drawn in the present

study?

29

With so many unanswered questions and so much promise of

future development and need, the field of creativity has

become a fascinating one for persons in a wide variety of

professions.

30

FOOTiWTES

lCharles S~mner Crow, Cre2tive Education (New York:

Inc., 1937), p. 226.

~rentice-Hall,

2;;.lice Miel, Creativity in Teaching (Belmont, California:

Wadsworth Publishing Co., 1966), p. 8.

3Jacob W. Getzels and Fhilip W. Jackson, Cre8tivit~ and

Intelligence - 1xplorations with Gifted Students (New York:

John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1962), p. 14.

4hie 1, p. 164.

5~braham Shumsky, Creative Teaching in the Elementary

School (New York: Af~leton - Century - Crofts, 1965), p. 53.

6Calvin W. Taylor and Faul Torrance, "Education and

Creativity", CreativiiY: Frogre~~ and Potential (New York:

McGraw Hill Book Co., 1964), p. 50.

7.r..dgar Dale, "Education for Creativity", The News

Letter, Vol. XXX No.3 (December, 1964), p. 1.

8 Ibid •

9Reginald 1. Archambault, "Education and Creativity",

Journal of General Education, Vol. XVII No.3 (October, 1966),

p. 55. lCRobert C. Wilson, "Creativity,lr iducation for the

Gifted, NSSE 57th Yearbook - Part 11 (Chjcago: University

of Chicago Press, 1958), p. 108.

llfi. Hurwi tz, ftCrea ti vi ty :~ues tions ,5nd .hnswers,"

School Arts, LXV (January, 1966), p. 16.

12£. Faul Torrance, "Creativity: What Research Says

to the Tea cher. II 1~i:Ji., Dept. of CIa ssroom Tea chers American

1ducational hesearch hssociation, No. 28 (April, 1963), p. 2.

131)a Ie, p. 1.

14Archambault, p. 202.

15Torrance, p. 4.

16F'rederick S. Breed, Education and the New Realism

(New York: The IvlacmillBn Co., 1939), p. 9l.

In'del, p. 61.

31

18Murray J. Lee and Doris M. Lee, "Creative Experiences:

l-'roviding for Creative Living", The Child and his Curriculum

(New York: Appleton - CeQtury - Crofts, Inc., 1960), p. 503.

19Ibid., p. 501.

20 Ibid •

21 Crow , p. 227.

22ShumSky, p. 208.

23lbid.

24wi llia m C .....olf Jr., "A Survey of be lieLs and

fractices Relative to Creativity," The Journ::.l of Educational

Research, Vol LVII No.7 (t-iarch, 1964), p. 3d4.

25Edward .Fred Stone, ",h Guide to Frinciples of

Creativity - In-- Teaching with Suggestions for Use in

.l:;lementa ry Soch,l Studies (Fa rts I a nd II), II Disserta tion

Abstracts, Vol. AXIl l-'t. 1 (July - October, 1961), p. 507.

26J esse ~. Bond, II l • na ly si s of Observed Trc::i ts of

Teachers rtated Superior in Demonstrating Creativeness in

Teaching," Journ&l of ~duco.l.ional Research, Vol 1111 i~o. I

(September, 1959), p. 11.

27Ib"d

'

__1_., p.o.

28Carol F. harshall, "Classroom Ferceptions of Highly

Creative and Less Creative Teachers in the Elementary School,"

Dissertation abstracts, Vol. XXIII Pt. 4 (April - June, 1963),

p. 369129Janet H. Gilbert, tlCreativity, Critical Thinking, arrl

Ferforrr..ance in Social Studies," Dissertation Abstracts, Vol.

XXII l-'t. 2 (November, 1961 - }ebruary, 1962), p. 1872.

3 0 Frank B. ~Iay, "Crea ti ve Thinking: A Fa ctoria 1 Study

of Seventy-Grade Children," Dissertation Abstracts, Vol. XXII

Ft. 2 (November, 1961 - February, 1962), p. 1&76.

3 1Donald J. Hadley, "Experimental Rela tionships

between Creativity and Anxiety," Dissertation .f-bstracts, Vol.

XXVI Pt. 3 (November - Lecember, 1965), p. 2566.

3 2David E. Day, "Crea ting a Clima te For Crea ti vi ty, It

School and Society, Vol. XCIV (October 15, 1966), p. 330.

33Ibid.

3 4 Taylor, p. 98.

32

35Shumsky, p. 49.

3 6 Ibid., p. 55.

371'Uel, p. IdO.

38Lbura L.irbes, Spurs to Creative 'leaching (New York:

p: 26.

G. F. futne~'s Sons, 1959),

391' rb nk ba rron, "l< reeing Ca pa ci ty to be Crea ti ve, 11

New Insights end the Curriculum (v.;a shington: Associa tion

~upervision and Curriculum Development, 1963), p. 292.

4eIbia., p. 31b.

41Teylor, p. 99.

42Torrance, p. 17.

4-3 u"h urns k y, p. 1.7

'"t •

44Calvin w. Taylor, fossible fositive and Negative

Effects of Instructional Nedia on Creativity (Salt Lake

City: university of Utah, 1960), p. 1.

45iorrance, p. 16.

46Dale, p. 3.

lil-'J-ENDIX

34

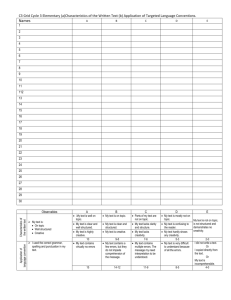

eva lua tion of the crea ti venES:-; (a ccoroing to a pa r ti Cllla r lis t of

factors) of the three stud8uts

interJiE~gd

and his/her own descrip-

tion of his/her own p&rticu]br aprroach to social studies.

teachers will be asked the same questions.

All of the

The interview should last

from five to ten minut2s.

Us.§_oLlnfortl}§;.li.QrL~

(1) The purpose of this study is not to make

judgments as to good or bad teaching in social studies.

Its purpose

is to determine the prsvclence of certain factors in social studies

teaching that receive the label Ilcreative".

(2) The names of

teachers and students will not appear anywhere in the report.

results of the study arc

~o

The

be ta"bula ted in a chi square table which

of course presumes anonymity.

Please notice at this time the enclosed card.

Bfter marking it

appropriately pleasQ drop it in a mailbox by Jonuary 20, 1968.

Reply

must be immediateJ

Once again 7 your cooperation will be greatly appreciated.

do not forget your sign&ture on the enclosed postcard.

Sincerely,

"

Please

described as whjch of the followinga"

u.."lit

b"

do

pro,ject

soc:.1alized

not anyone cLettlod} but

e.

problem solving

c.

(If ,you use the uni t af,prOB(.:h')

combina tion of methods

B

Do YCYU feel. obliga ted to include every

subject area in the t..m.i t?

Do you ever d,etect an a tmospb6u.'(~

thel~

";suspcnsion" or individua Is being

0<'

completely

ab~orbed

examples,>

Could you plea se desc:ei\"e HI€ soci£' 1 stl.ldiE!S projects in

in

the2u.C(~\:;~:;;:'

How would you descd.bo

Do you

y~)U

have hod in employing the problem

a?proach~

e~er

attempt 5ctivities in jour classroom which you consider

unusual and ",bout which

Can

Explain--specific

engaged'~

which your Glass has

solving

social studies work?

'y1:)1l

tell ':u.e about an

any role playing or

i-:-l to:rm3 of ov,tcome

you~

e:~r.ur;~:lon

In what capacity have

insecure?

ycnlr class has made this year'?

they have

dl'am&.tiz~~ti('Hl

fE~el

en~aged

About

in?

used s:tudy g',l1.des?

yQU

in; interviewed on & scale of 1-4 (one 1s

Classify each of trle stuclent2

the highest rattng :lnd:!.e.atlng)oss'::tss:L:m. of this ch[;..racteristlc to a great

degree)

av

b.

c"

do

ver1)al facilil:y

verbal flueuc,:,

flexibili ty

unique ~nd workable ideas when presented

routine problsffis

or1~inalitY--trodGce3

-

tith

What is your recjctlon to

6

interviewed to be described

ue~ Q~

ch:LJ.(

~s

1.\fbo

ebB

this way?

be ()escl'ibed

tJS:

quieseent'l \I/lth=

36

ne

·V·~$

~.QM"'..r"

~,.!t1;rr}

by

}f'Ol~

.r.·r,:r~·

.:J\:'m$('n~

t(;

W(~:rk:~j1L'

t TY

!~orl~ '1:~";';

f)fT:

I~gnir~?

..~{:

"~~ • • t""''l~JV·",

;~:}-=-2f.r

;.r>:)~~2:

t'c nC ,c, r~

~.

If

Vf.~;;'

'co?

11e )'0 '\.1 f~;H"Jl fr*~1;" 'tv i';')q:la'r~'1 anc f ~,;q:"~,,~,,,,'i;n:,:'nt 111~1';~h

th<.';' 1/';1,cHiSE";)OtU th:l.tS '"vn."rr,.1

·'::S

"'v 1"'iv(l,

... ",,,,,~<.,,,"

".n_.....~.

~ ....~ .'

y'1}\,~

.4r6

ttl)

~1·'!rar.i

dSf:id~

~'o,r

.iftSt..!~t:f;.:'t·!on~r::

Y('.H1J'!H~:tf

ro~: Io·~.!

t·n

C:'~{';(;J

ii'

€'

~,~_l',

;'i~l")'e

"'::il~~

),~·,u

y,~~s,

'Fba?

'~~~t1t~j

_ _ _ .......lIo,oI.oo .._ _ ....... I·

•

thtng~~

["'~;

~n(:,)ul"aged

i>&<&-

on your' o'!;rn in

on -y",'.l;;;' "wn)

X!J~H.lL\r('h

1~K"

:t.r(~

~"i}U

allt,1w'ed

hrH' ytH. \;jou1d 2:lko to d(l

s.('Hlle~,

thi rag?

you enoouraged to

~re

D~'\l

YOUT

cle.!u;rtt.at~gt

a~k

fH~k

i.l!

_

qUDSt~01S

10 ~

~;.f

........._-..C?-',,'W .•

1n class?

(1l:'.H~~;tjons

)'08

j

ves

---.~

Does anyone?

__yes

no

n

r~o

, .... ...)' 6S

Dc::qu.

Y~H~r-

lftaaohf:u" t;..",lj 'Dye

cve~·:,··-<;i~.i~g

she

no

-----....

~HH!2

• _ _rlO

1.n the

t(,ztbO~"5?

--no

Can Y"'iU t€tll f?~~lI.0·";;!..(jt);l>.~~ e-ach cthe<' hoft!

thing 10 lrla~ls?

.. -.)1 os ----.. niil

.

y~u

think o:r :lael about

s():~e"",

\,ben you and yOUi' cla!tSl;1atl)S hr:tV·;j a problem to silve do you decidE

what to do yourselj'e~ ~'r does your tl.'l~.{;h('il" decide fOJ' Y0lol?

---_.

tea~her

37

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

breed, rrederick S. E,duca tioD a nd The New Rea lism.

York: The }~cffiillan Co., 1935.

Crow, Charles S. Creative Education.

hall, Inc., 1937.

New York:

New

Frentice-

uetze Is, Ja cob W., G. nd J&ckson, 1 hi lip W. Crea ti vi tv and

Intelligence - EXQlorations with Gifteq Students.

New York: ~iley, 1962.

Gowan, John C., ed. Creativity:

New York: ~iley, 1967.

Its

~ducational

Implications.

Gruber, Howard E.; lerrell, Glenni and Wertheimer, Michael.

Contemlorary .fip:proaches to l,;reative Thinking. New

York: Atherton Press, 1963.

Lee, Nurray .I., and Lee, Doris t<:. The Child and His

Curriculum. New York: hrpleton - Century - Crofts,

Inc., 1960.

Narksberry, h&.ry Lee. foundation

Harper &nd how, Inc., 1963.

Miel,

QQ

~~lice.

Creetivity in Ie&.(!r~ing.

~adsworth fublishing Co.,

1966.

Creativity.

New York:

Eelmont, California:

Creativity in 'leaching: InvitGitions and

Instances. belmont, California: Wadsworth Fublishing

Co ~, 1961.

farnes, 3idney J., and Harding, Harold F., eds. 2 Source

Book for Creative thinking. New York: Chcrles

Scribner's Sons, 1962.

ho trick, Ca Lharine.

wha t is Crea ti ve l'hinking.

fhilosophical Library ~ssociaticn, 1955.

1\eed,

New York:

Develoring Creative Talent - ~'-I.n b.dventure in

'lhinkirrg. New York: Vantage Fress, 1962.

r:;.

Seidel, G. J. The Crj_sis of Creativity.

Notre Dame Press, 1966.

r~otre

Dame, Ind.:

ShumSh. y, nbraham. Creative fe&.ching in ihe Blementary

School. New York: Appleton - Century - Crofts, 1965.

38

Srr.ith, JiSmeS .~. Creative Tes.ching of §Qcial ;3tudies in the

Lleruentsry School. Doston: hllyn ond bacon, 196'/.

Setti:lK Conditions for Creative Teaching in the

61ementE.ll School. boston: ./"l.11yn end Bacon, 1966.

Tay lor, Co. 1 vin ',,>/., ed. CreE:. ti vi ty : Frogres s

~ew York:

McGraw - Hill, 1964.

&

nd Foten tia 1.

Torra nce, E. 1-8 ul. l;eve lafme:; t and .i..VE:. Ilia tion af B~corded

Frogrbmmed Lxperiences in Creative Thinking.

~inneapolis:

University of Minnesota Fress, 1964.

Von Fange, iugene K. frofessional Creativity. ~nglewood

Cliffs, New Jersey: Frentiee - Hill, Inc., 1559.

iies ley, Bruce E. Teaching the Socia 1 Studies.

D. C. Heath and Co., 1942-.----lirbes, Laura. Slurs to Creative Teaching.

P. Futnam's Sons, 1959.

bos ton:

New York:

u.

Yearbooks

barron, Frank. "Crea tive Vision and 8xpressi.on, I' New

InSights and the Curriculum. 1963 Yearbook of the

Association for Supervision and Curriculuffi Development.

~dited by ~"lexander rrazier.

~\ashingt()n, L. C.:

b. S. C. D. Fublications, 1963.

Franseth, Jane. "l'reeing Capacity to be Crec~tive,I' New

Insights and the Curriculum. 1963 Yearbook of the

Association for Surervision and Curriculum Development.

bdited by alexander ~razier. W6shington, G. C.:

~. s. C. D. Publications, 196~.

wilson, rio bert C. "CreCi. ti vi ty ,II Ed uca ti ::m f<ll: the Gifted.

Fifty-seventh Yearbook of the Nationsl Society for the

Study of Lducation, PErt III. ~dited by Nelson E.

Henry. Chicago, Illinois:. University of Chicago

rress, 195cL

[-{eports

}\nderson, Harold H., ed. Interdisciplinary ~~ymposia on

Crea ti vi U. i~ew York: He rper fress, 1959.

Conant, James B.; strang, huth; and Willy, Paul. Creativity

of Qifted and Talented Children. Addresses to the

~rr.erican rissociation for Gifted Children, New York.

New York: Dureau of Fublications, Teachers College,

Columbia University, 19591

39

farber, Seyn:our l/~. c;n( wilson h. H. L., eds • .t-Ian. and CiviliZe tion: ~on[lict and Creb ti vi ty; .!l Sy muosi urn. l~ew

York: Iv.clIrsw - Hill, 1963.

Ghiselin, Brewster. The CrEative Frocess, ~Symposium.

berkeley: University of California Press, 1952.

laylor, Ce,lvin '.N. Possitle Positive and Negativ~ Effects of

Instructionc.l .t-iedia Qll Creativity. h.SCD eND';.) Project.

Sc,lt L&.r.:e City, Utah: NaticGal Educationsl l,ssociation

}ublic~tion, 1960.

Studies

Bond , Jesse A.

"t~na ly sis of Observed Tra i ts of Tea chers

Rated Superior in 0err:onstrating Creativeness in

TE?a ching. II J our!l~l of 1:;d uca tic'na 1 .Rese'a rch. Ll I 1

(3eptember, 1955), 7-12.

"ri Ibert, Jc:net E.

"Crea ti vi ty, Cr i tica 1 Thinki ng and

Ferformbnce in tJocial Studies.'1 Dissertation ~bstracts.

LIll No. 1 (~epteffiber, 1959), p. 11.

Greif, Iv.:> F. "l-,n Inves tiga tion of the Effect of a Dis tinct

L(Lpha sis on Crea ti ve ano Cri tica 1 Thinking in tea cher

i.ducation." Dissertation Abstracts, XXII, rt. II

(jovember,.1961 - february, lS62), 1076.

Hadley, .0onald J.

'ILxperim~nta 1 Rela tionships between

Crea ti vi ty and .i-.n:d.ety. 'I Dissert::. tion Abstracts, XXVI,

(November, 1965 - December, 1965), 2586.

H&rris, Richard H. liThe lJevelopment and Valj_dation of a

Test of Creative Acility." Doctoral Dissertation

Series, Fublica tion 1,0. 13, 927. Ann .~rbor, Michigan:

University ~icrofilms, 1955.

Harsha 11, C& rol F. "CIa ssroom F erceptions of Highly Crea ti ve

end Less Creative Teachers in the £lement&ry School.'1

Dissert&tion ~bstracts. XXIII, Ft. IV (April, 1963 June, 1963), 3691.

N&y, rrL.nk b. "Creative Thinking: l'. Bacterial Study of

Seventh-Grade Children." 1issertbtion ~bstracts.

XAII, ft. 2 C~ovemter, 1961 - February, 1962), 1276.

Stone, Edward F. "n GiJide to frincirles of Crea ti vi ty - In teaching ~ith 3u;gestions for Use in Element&ry Social

,studies. I! Lissert&tion fibstr&cts. XXII, 507.

liJodtke, K. E., and ""allen, N. E. "Teacher Cl8ssroom Control,

Fupil CreatiVity, and fupil Classroom Dehavior."

Journal of .t;xperimental Education. AXXIV (Fall, 1965),

59-65.

40

l\rticles

... rchamba ul t, Regina Id D. "Ed uca tion and Crea ti vi ty. "

Journal of General .c;ducbtion, AVIII, No.3 (October,

1966). Earron, It'rbnk.

I'Creati'vity: What Research Says Jibout It."

N£J-"> Journal, L (Barch, 1961), 17-19.

Dole, Eagar. "Education for Creativity." The News Letter,

Vol. 30, No.3 (December, 1964), 1-3.

Day, Do. Vid. B. "Crea ting a Clima te for Crea ti vi ty. I'

and Societ2, ALIV (October 15, 1966), 330-4.

School

l<orslund, Janet.l:.:. "Inquiry into the Nature of Creative

of Creative Teaching." JO!!rnal of Education, XIV

(h~ril, 1961), 72-82.

Hallman, R. J.

"Commonness of Creativity." Educational

Theory. Vol. 13 (rlpril, 1963), 132-6.

harris, Kenneth. "Don't Stifle Your Students' Nonconformity." NLi> Journal, LV (October, 1966), 24-26.

Hearn, N. E. "Change for the Sake of Change: Why Not'(

fHCE; l-'rojects to Advance Creativity in Education. I'

N&tional Elementbry Frincipal, ~LVI (September, 1966),

50-2.

Hughes, L. E.

lI~duca tion for Crea ti vi ty ," Overview, I I

(July, 1961), 33-9.

Hurwi tz, f>..

"Crea ti vi ty : "iues tions and Answers."

Arts, LAV (January, 1966), 30-3.

School

Lessinger, L.

"Characteris tics of Crea ti ve Tea chers. "

Journal of Secondary Education, XAXVIII (Ns.rch, 1963),

182-6.

"r os tering Creb ti vi ty ."

LAXVII (l-larch, 1967), 97.

:r.:a rksberry 1 H. L.

]Lns tructor,

Peabody, Scholl S. "Cultivation of Creativity."

of Educ&.tion, ALIV (J:.;arch, lS67), 282-5.

rlhodes, 1vlel.

I'.r'.n Analysis of Creativity."

Vol. 42, No.7 (april, 1961).

Journal

Jhi Delta

~~,

Rubin, 1. J.

"l ea ching for Crea ti vi ty . II Ca lifornia J ourna 1

of Secondc~ EdUCation, AAXV (December, 1960), 4l6-91.

41

Se linger, A. W. "f-roj ec t tipproa ch to Identifying and

Encouraging 3tucent CreativitY,1I Californi~ .education.

(February, 1966), 11-12.

,st&nistreet, G. Iv:.

IIReal Hearling of Creativity,"

llJ.. (September, 1960), d.

Instructor.

Taylor, C. W.

III::ffects of Instructional Media on Creativity."

Educational Leader, AlA (npril, 1962), 453-56.

'l'rabue, 1'1.. 1,.• "Observations on Creativity.1I

}orum, X.iVII (November, 1962), 55-65.

,~eir

Educational

, E. C. "Choice and Creativity in Teaching and Learning."

Phi Delta Kappan, ALIII (June, 1962), 408-10.

Wilson, .n. C.

"Developing Creativity in Children."

Educator, 11..11..)(.1 (September, 1960), 19-23.

"""olf, 'vdlliam C.

"Survey of Beliefs and Frsctices helative

to Crea ti vi ty. II Journ& 1 of Educa tione> l Research,

L'J.VI1 (March, 1964), 304-85.

'Welman, tI..

IICultural F&.ctors and Creativity." Journal of

Secondary Education, AXXVII (December, 1962), 454-60.

Tape Becordings

Sornson, He len H.

"i-.re You a Crea ti ve lea cher? II Commencement

Semin&r, ball State Jniversity. fhonotape recorded in

Muncie, Indiana, June 3, 1961. ball State University,

Teaching Materials Service.

Sornson, Helen H.

"Interes t and Crea ti vi ty. 11 } honotape

recorded in Kuncie, Indiana, 1'I.pril 14, 1964. Ball

.state University, Teaching Eaterials SE~rvice.