Document 11212119

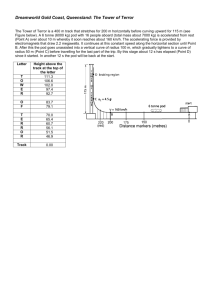

advertisement