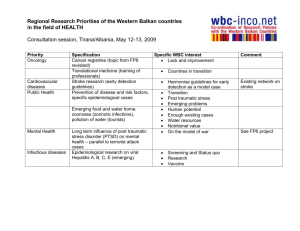

How emerging markets are driving the transformation of

advertisement