The Ideology of Madness in the Media:

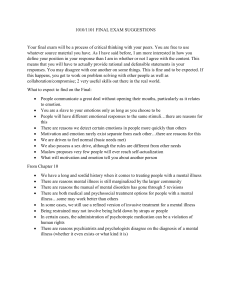

advertisement