An Apocalypse of Change: By Kellen O’Gara

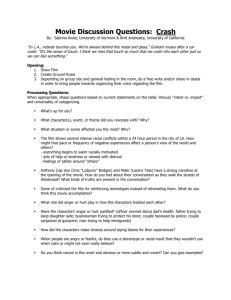

advertisement