! "#$%#&$&'!()*!+*,-&$&'!*&.$-#&/*&(0! 1-*,($&'!/#-*!%",1*!2#-!%(34*&(!%"**1)!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

"#$%#&$&'!()*!+*,-&$&'!*&.$-#&/*&(0!

!

1-*,($&'!/#-*!%",1*!2#-!%(34*&(!%"**1)!

!

!

56!

!

789:;9:!4<=>?98@6!!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

,!%A?<BC8!<D!@?9!1<BB9>9!(?9EFE!

E=5GF@@9;!@<!@?9!1<BB9>9!<D!,8@E!C:;!%AF9:A9E!

C@!7<E@<:!1<BB9>9!!

!

(?9EFE!,;HFE980!48I!)9859AJ!

!

/C6!KLML!!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

Copyright by

BRENDEN DOUGHERTY

2010

All Rights Reserved

To my parents:

For their unconditional faith in me

!

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter

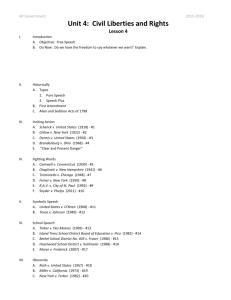

I. CHASE HAPER AND THE FIGHT FOR FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION . . 1

The Law of Student Speech . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Pure Student Speech . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Tinker : The Landmark for Student Speech . . . . . . . . 7

Bethel : The Court Strikes Down “Lewd” and “Indecent” Speech . . . 14

Morse : The Court Strikes Down Drug Speech . . . . . . . 21

School Sponsored Student Speech . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Hazelwood : “Legitimate Pedagogical Concerns” . . . . . . . 27

The Legacy of Hazelwood . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Harper v. Poway Unified School District . . . . . . . . . . 38

District Court Decision . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Decision . . . . . . . . . 40

II. TINKER : THE FLAWED STUDENT SPEECH STANDARD . . . . . 43

“Rights of Others:” A Flawed Test . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

Not the Determinate Test Within Tinker . . . . . . . . . . 45

An Ambiguous Test . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

An Impending Snowball Effect . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

“Substantial Disruption:” A Flawed Test . . . . . . . . . . 55

An Ambiguous Test . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

Ambiguity Allows for Anticipation . . . . . . . . . . . 56

Ambiguity Allows for Over Breadth . . . . . . . . . . . 63

Unfit For the 21 st Century . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69

III. A NEW APPROACH TO STUDENT SPEECH . . . . . . . . . 77

The First Prong: Is the Speech Worthy of Protection? . . . . . . . 78

Age Inappropriate. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

Graphic Sexual Content or Images . . . . . . . . . . 81

Harassment or Speech that Targets an Individual Student . . . . . 85

“True” Threats . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88

The Second Prong: Does the Speech Poison the Learning Environment? . . . 92

Educating the Student Citizen . . . . . . . . . . . . 92

“Poisoning” the Learning Environment . . . . . . . . . . 96

Possible Objections to the Poisoning Standard . . . . . . . . . 98

An Application of the Poisoning Standard . . . . . . . . . . 106 !

!

CHAPTER ONE:

CHASE HARPER AND THE FIGHT FOR FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION

!

Poway High School, located in Southern California, has served as a forum for particularly contentious debates over the last decade with regard to the acceptance of homosexual students. The contentious nature of these debates became visible for the first time in 2003, when school administrators deemed it acceptable for the student group known as the “Gay-Straight Alliance” to organize a “Day of Silence,” a day focusing on the self- worth of those of a different sexual orientation. Those students who participated in the “Day of Silence” chose to wear duct tape over their mouths in order to illustrate the point that discrimination against those of a different sexual orientation has a tremendous

“silencing effect.” Several participating students also wore black shirts that contained the words “National Day of Silence” on them. In addition, the Gay-Straight Alliance also received permission from administrators to put up posters throughout the school containing information regarding the prevalence of harassment based on sexual orientation and the dangers associated with such attacks.

1

What arose as a result of this celebration of toleration was a significant amount of animosity between those students who favored acceptance of homosexual pupils and those who expressed anti-homosexual sentiments. In at least one case, the animosity

1

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Harper v. Poway Unified School District , 445 F.3d 1166, 1171 (9 th Cir. 2006). The facts of this case are based on: Andrew Canter and Gabriel Pardo, “The Court’s Missed

Opportunity in Harper v. Poway ,” Brigham Young University Education and Law

Journal 2008 (2008), 125; and Douglas D. Frederick, “Restricting Student Speech that

Invades Others’ Rights: A Novel Interpretation of Student Speech Jurisprudence in

Harper v. Poway Unified School District ,” University of Hawai’i Law Review 29

(Summer 2007), 492.

!!

1

!

turned physical and, according to the recollections of one teacher at Poway High School, several students were suspended due to their involvement in altercations stemming from the “Day of Silence” celebration. And the effects of the “Day of Silence” did not stop there. Indeed, a week after the celebratory day, a collection of Poway students came together to informally hold a “Straight-Pride Day” within school grounds. Directly opposed to the “Day of Silence,” the “Straight-Pride Day” participants despised those of different sexual orientations and displayed their disapproval by wearing shirts to school which depicted anti-homosexual phrases. Many of these participants were asked by

Poway administrators to remove their anti-homosexual t-shirts, and while some complied, others became involved in altercations and were subsequently removed from the school environment.

2

Despite the conflicts surrounding the 2003 “Day of Silence,” the Poway High

School Gay-Straight Alliance proposed yet another day of toleration towards those of different sexual orientations the following year in 2004. While administrators accepted the alliance’s request, they first asked the organization to hold a meeting with the school’s Principal in order to brainstorm ways in which to better prevent altercations amongst students. This second day of toleration kicked off as planned on April 21, 2004, with the blessing of Poway administrators. As was the case with the 2003 “Day of

Silence,” participants in the 2004 event wished to promote awareness concerning the presence and debilitating effects of harassment based on sexual orientation. However, while this was the purpose as understood by administrators and organizers of the event, this was not what some students believed to be the true reason for the event. One such

!

2

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

445 F.3d 1166, 1171 (9 th Cir. 2006).

2

!

skeptical student was a young man by the name of Tyler Chase Harper. Rather than accept the publicized goal of toleration as proclaimed by the Gay-Straight Alliance,

Harper developed his own theory regarding the purpose of the “Day of Silence.”

According to Harper, what the Gay-Straight Alliance really wanted to do in organizing this day of toleration was “endorse, promote, and encourage homosexual activity.” 3 As a devout Christian, Harper was unwilling to accept such a sinful goal. Steadfast in his beliefs, Harper decided to take matters into his own hands.

On April 21, 2004, the day Poway administrators had approved as the “Day of

Silence,” student Tyler Chase Harper arrived at school wearing a t-shirt containing two handwritten phrases. On the front of the t-shirt was the phrase, “I WILL NOT ACCEPT

WHAT GOD HAS CONDEMNED.” On the backside of the shirt, Harper had written the phrase, “HOMOSEXUALITY IS SHAMEFUL ‘Romans 1:27.’” Although this was the official “Day of Silence” at Poway High School and much attention was paid to the issue of sexual orientation, Harper went through the school day undisturbed. The following day, April 22, Harper again wore a shirt to school containing anti-homosexual phrases. While the writing on the back of the shirt remained unchanged from the previous day, the writing on the front of the shirt had been altered to read, “BE

ASHAMED, OUR SCHOOL EMBRACED WHAT GOD HAS CONDEMNED.” 4

Unlike the t-shirt Harper wore during the actual “Day of Silence,” this second shirt drew the attention of Poway administrators. Upon seeing the anti-homosexual phrases, Harper’s second period teacher, Mr. David LeMaster, requested that Harper take

!

3

4

!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

445 F.3d 1166, 1171 (9 th

445 F.3d 1166, 1171 (9 th

Cir. 2006).

Cir. 2006).

3

!

off the item of clothing. Recalling the confrontation surrounding the 2003 “Day of

Silence,” LeMaster explained to Harper that his shirt was “inflammatory,” a violation of the school’s dress code, as well as an item that “created a negative and hostile working environment for others.” When Harper refused to remove the t-shirt, Mr. LeMaster awarded him with a dress code violation card and sent him to Poway’s administrative office.

5

When Mr. Harper arrived at the office, Assistant Principal Lynell Antrim greeted him by explaining to him that his t-shirt was likely to cause “disruption in the educational setting” and needed to be removed. In addition, Ms. Antrim discussed with Harper the more appropriate ways in which viewpoints regarding homosexuality could be expressed within the learning environment. Despite this conversation, Harper still refused to comply with administrators. As a result, Harper was made to see the Principal of Poway

High School, Mr. Scott Fisher. During the conversation that transpired, Mr. Fisher explained to Harper that his intent was to prevent violence from erupting on campus, and that the derogatory language contained within Harper’s t-shirt was likely to incite confrontation. The confession by Harper that he had already been “confronted by a group of students” and “involved in a tense verbal conversation” earlier in the school day only strengthened Principal Fisher’s resolve to see Harper’s shirt removed. Although

Harper later maintained that this conversation was merely a peaceful talk “wherein differing viewpoints were communicated,” Principal Fisher took the contentious discussion as further evidence of the likelihood of violent altercations. Following

Harper’s refusal to accept any of the alternative modes of expression suggested by Mr.

!

5

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

445 F.3d 1166, 1172 (9 th Cir. 2006).

4

Fisher, the young man was ordered to remain in the front office for the remainder of the school day.

6

Following this incident, Harper filed a lawsuit in the United States District Court for the Southern District of California. The suit alleged that the Poway school district had violated Harper’s free speech rights by forcing him to remain in the front office while wearing the controversial shirt.

7 This lawsuit raises many questions as to what the acceptable forms of expression in the school environment are. Indeed, what First

Amendment rights are afforded to students in America’s public schools? How much discretion do administrators have in banning instances of student speech? Were the actions of Poway administrators, in forcing Tyler Harper to remain locked away in the school’s main office, permissible under the law?

In order to better understand the answers to these questions, one must look at the current body of Supreme Court precedence that rules over student speech. These cases, which comprise two distinct branches, determine the fate of all instances of student expression in today’s public schools. The first branch of cases deals with instances of

“pure student speech,” or instances of expression completely independent of the public school system. In these cases, students chose to express themselves through the use of their own materials, with no input or support from school administrators. The second branch of cases deals with instances of school-sponsored expression. In these cases, students chose to express themselves through various school-sponsored mediums. These

!

!

6

7

!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

445 F.3d 1166, 1172 (9 th

445 F.3d 1166, 1173 (9 th

Cir. 2006).

Cir. 2006).

5

!

two lines of case law currently determine the constitutionality of student speech within

America’s public school system.

The Law of Student Speech

The freedom of men and women to express themselves is one of the most prized rights under the Constitution. This freedom allows for minority viewpoints to be heard and for robust debate among citizens. Students, as American citizens, enjoy this constitutional right within the school environment. Indeed, the presence of this right within the public school system was affirmed at the close of the 1960’s in a landmark

Supreme Court case. However, in the four decades since this landmark decision, the

Supreme Court has recognized on two occasions the need to place certain restrictions on the First Amendment rights of pupils. Recognizing the need to set boundaries in an environment primarily meant for the instruction of society’s youth, the Supreme Court in the 1980’s, and then again in 2007, placed limitations on the extent of free speech rights afforded to students.

“Pure” Student Speech

The current body of law regarding student speech can be broken up into two distinct branches. The first branch deals with instances of “pure speech,” or speech

6

totally independent of school sponsorship. The first major case within this branch is

Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District .

8

Tinker : The Landmark for Student Speech

The facts surrounding this case unfurled against the backdrop of one of the most tumultuous conflicts in American history. The year was 1965, and President Lyndon

Johnson was escalating hostilities in Vietnam. The American public was growing louder in protest, even within the small population of Des Moines, Iowa. It is here where the story at the center of the first major case on student speech rights began.

In December of 1965, a meeting was held at the home of a family who resided in

Des Moines, Iowa. The family name was Eckhardt, and the members of this family were staunch opponents of the conflict in Vietnam. Indeed, the Eckhardt family was very upset by the escalating violence and increased American presence in the distant Asian country. Wanting to do something to show their disapproval of the war, the Eckhardt family decided to invite other families within the Des Moines school district who opposed the Vietnam conflict to their home for a brainstorming meeting. Out of this gathering grew a plan of protest in which participants would wear black armbands throughout the Christmas season and fast for two full days, on December 16 and New

Year’s Eve. Among those who agreed to participate in the protest activities were high

!

!

8

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District , 393 U.S. 503 (1969).

7

school students John F. Tinker and Christopher Eckhardt, as well as John’s sister, junior high student Mary Beth Tinker.

9

Soon after this meeting at the Eckhardt home, administrators within the Des

Moines district became aware of the planned armband protest. In an effort to stifle the expressive act, Des Moines school officials adopted a school policy that stated that “any student wearing an armband to school would be asked to remove it, and if he refused, he would be suspended until he returned without the armband.” 10 Despite hearing about the new school policy regarding black armbands, the student participants in the protest chose to wear the expressive items anyway. On December 16, 1965, Christopher Eckhardt and

Mary Beth Tinker put on their black armbands and walked proudly into their respective high school and junior high school. Mary Beth’s older brother John chose to put on his armband the following day. As was promised under the new Des Moines district policy, all three students were immediately suspended from school pending the removal of their armbands. The students remained steadfast in their act of protest however and did not venture back onto school grounds until after New Year’s Day, which was the final day of the protest.

11

Following the suspension of these students from the Des Moines public school, the parents of Christopher Eckhardt and Mary Beth Tinker filed a lawsuit in the United

States District Court, claiming a violation of the students’ First Amendment rights. In

!

9

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

393 U.S. 503, 504 (1969). The facts of this case are based on: Edgar Bittle, “The Tinker

!

!

Case: Reflections Thirty Years Later,” Drake Law Review 48 (2000), 491.

10 393 U.S. 503, 504 (1969).

!

11 393 U.S. 503, 504 (1969).

8

!

ruling in favor of Des Moines school officials, the District Court for the Southern District of Iowa stated that administrators were justified in forbidding the wearing of armbands, considering the need to prevent disruption in the school environment. Indeed, the district court held that “it was not unreasonable in this instance for school officials to anticipate that the wearing of arm bands would create some type of classroom disturbance.” 12 The case then moved to the Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit, which was equally divided on the issue and was subsequently forced to affirm the judgment of the district court.

13 Petitioners on behalf of the students then appealed the case to the Supreme

Court, which granted certiorari and considered the matter.

14

In writing the majority opinion for the Supreme Court, Justice Fortas affirmed the presence of the First Amendment in the learning environment by declaring that pupils do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” 15 Indeed, the Supreme Court dismissed the notion that the school environment should not be bound by the Constitution and instead held that students are real citizens who hold rights even within the educational setting.

To further emphasize the importance of the First Amendment in the public school,

Justice Fortas looked to the words of Justice Jackson in the opinion for West Virginia v.

Barnette . In upholding the right of a public school student to refrain from saluting the

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

12 Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District , 258 F. Supp. 971, 973

!

(S.D. Iowa 1966).

13 Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District , 383 F.2d 988 (8 th Cir.

!

!

1967).

14 393 U.S. 503, 505 (1969).

!

15 393 U.S. 503, 506 (1969).

9

!

United States flag, Justice Jackson reminded school administrators that their purpose in the classroom was to educate the youth for citizenship and warned them not to “strangle the free mind at its source and teach youth to discount important principles of…government as mere platitudes.” 16 In referring back to these words by Justice

Jackson, Justice Fortas impressed upon his audience the Court’s history of protecting students’ rights and the importance of upholding the reality of the United States

Constitution in the public school.

In his opinion, Justice Fortas built a great deal upon the notion that the First

Amendment is a right that applies to students as well as adults. For, as Justice Fortas articulated, pupils are people too under the Constitution. And like all other United States citizens, students are “possessed of fundamental rights which the State must respect.” 17

The Justice stressed that the architects of the Bill of Rights did not intend for the First

Amendment to be applicable only to certain people in restricted circumstances. Indeed, the First Amendment was not meant to apply only to adults in telephone booths. Rather,

Justice Fortas contended that the opposite is true, in that First Amendment rights are only to be denied in limited circumstances.

18 In addition, Justice Fortas made certain to emphasize the vital nature the First Amendment plays in the learning environment.

Nowhere, exclaimed the Justice, is the protection of the First Amendment more crucial than in the public school system. Indeed Justice Fortas contended that the classroom should be thought of as a “marketplace of ideas.” The Justice considered the marketplace

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

16 393 U.S. 503, 507 (1969).

!

17 393 U.S. 503, 511 (1969).

!

!

18 393 U.S. 503, 513 (1969).

10

!

an ideal metaphor for the public school setting, pointing out that the future of America depends upon an educational environment where the youth are exposed daily to the

“robust exchange of ideas which discovers truth ‘out of a multitude of tongues, [rather] than through any kind of authoritative selection.’” 19

In writing his opinion, Justice Fortas dismissed the contention of the Des Moines administrators that they were forced to remove the armbands due to their perceived fear of a disturbance within their schools. Indeed, Justice Fortas deemed “undifferentiated fear” an unacceptable reason to justify the curtailing of the First Amendment rights of students. The Justice pointed out that any difference of opinion among students has the potential to cause a “disturbance.” However, according to the Constitution, this is the type of risk that Americans are compelled to bear.

20 For, as Justice Fortas stated, it is the acceptance of this risk of disagreement that is “the basis of our national strength and of the independence and vigor of Americans.” 21

In affirming the presence of the First Amendment in the school environment,

Justice Fortas made it clear that judgments regarding the censorship of student speech should not be left solely to the discretion of school administrators. Indeed, Justice Fortas noted that, “school officials do not possess absolute authority over their students.” 22 By saying this, Justice Fortas affirmed the notion that the federal judicial system should be charged with analyzing instances of student expression and upholding the rights of

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

19 393 U.S. 503, 512 (1969).

!

20 393 U.S. 503, 508 (1969).

!

!

21 393 U.S. 503, 509 (1969).

!

22 393 U.S. 503, 511 (1969).

11

students as American citizens. Indeed, rather than submit to the idea that school officials have complete authority to censor whatever they deem inappropriate, Justice Fortas made it the duty of the courts to determine what student speech is constitutionally permissible.

While Justice Fortas did reassert the presence of the First Amendment in the public school with his majority opinion in Tinker , he did not grant students free reign to express whatever they wished in the classroom. For in addition to declaring that students did receive protection under the First Amendment, Justice Fortas also put forth two important limitations on student speech rights. In creating the first exception, Justice

Fortas stated that any speech that would “materially and substantially disrupt the work and discipline of the school” was not to receive protection under the First Amendment.

23

In creating the second exception, Justice Fortas held that any speech that would collide with the “rights of other students to be secure and to be let alone” was also not deserving of First Amendment protection.

24

Keeping these two exceptions in mind, Justice Fortas determined that the black armbands worn by Mary Beth Tinker and other Des Moines students were protected items of speech. In terms of whether the armbands fit within the first exception to student speech rights, Justice Fortas noted the fact that only a few students participated in the protest and the fact that no threats or violent acts occurred on school premises while the students were wearing the armbands. Based on these facts, Justice Fortas concluded that the armbands did not fall within the grasp of the first exception.

25 Justice Fortas also

!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

23 393 U.S. 503, 513 (1969).

!

24 393 U.S. 503, 508 (1969).

!

25 393 U.S. 503, 508 (1969).

12

deemed the armbands separate from the second exception, stating that the armbands constituted a “silent, passive expression of opinion” that did not interfere with the rights of other students in any way.

26 Having declared the armbands separate from both exceptions to student speech rights, Justice Fortas classified the black accessories as protected items of speech under the First Amendment.

While the majority of the Court in Tinker concluded that the expressive armbands were protected items of speech under the First Amendment, the decision was not unanimous amongst the justices. Justices Black and Harlan offered scathing dissents of the Fortas opinion, claiming that the majority viewpoint would lead to chaos within the public school system. By Justice Black’s understanding of the record, the black armbands “did exactly what the elected school officials and principals foresaw they would, that is, took the students’ minds off their classwork and diverted them to thoughts about the highly emotional subject of the Vietnam War.” 27 Considering this distracting effect of the armbands, in addition to the fact that “public school students are (not) sent to the schools at public expense to broadcast political or any other views to educate and inform the public,” Justice Black opined that school officials were well within their rights to forbid the wearing of the armbands.

28 However, the majority of justices did not agree

!

!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

26 393 U.S. 503, 508 (1969).

!

27 393 U.S. 503, 518 (1969).

!

!

28 393 U.S. 503, 522 (1969).

13

with this viewpoint, prompting Justice Black to predict that future students “in all schools will be ready, able, and willing to defy their teachers on practically all orders.” 29

While Justice Black did not see the benefit of affirming the constitutionality of the expressive armbands, the majority did, and thereby crafted the first major standard for student speech rights. Albeit with two major limitations, the Court held that students are to be afforded First Amendment rights within the school environment. For the next decade and a half, the Tinker decision remained the only Supreme Court precedent concerning students’ “pure” speech rights. However, beginning in the mid-1980’s, the

Court began to consider the issue of student speech once again. Rather than expanding the First Amendment rights afforded to students, these subsequent decisions by the

Supreme Court placed further limitations on the breadth of constitutional protection given to pupils. The first of these limiting cases was Bethel School District No. 403 v. Fraser .

Bethel : Court Strikes Down “Lewd” and “Indecent” Speech

This case arose from a speech that took place during a school assembly on April

26, 1983. Administrators at Bethel High School in Pierce County, Washington, had set up the assembly as part of a school-wide lesson in self-government. Approximately 600 students gathered to take part in the assembly. A young man by the name of Matthew

Fraser was one of the students scheduled to speak during the assembly. His address was a nomination speech for a Bethel High school student who was running for student

!

!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

29 393 U.S. 503, 525 (1969).

14

government.

30 Fraser’s speech, as defined by Chief Justice Burger of the Supreme Court, was designed using an “elaborate, graphic, and explicit sexual metaphor.” 31 In his speech, Fraser referred to his candidate as a man “firm in his pants.” Fraser continued the sexual metaphor by exclaiming that his candidate was a man who would “take an issue and nail it to the wall.” Fraser also assured assembly viewers that his candidate was not one to “attack things in spurts,” but rather was a man who “drives hard, pushing and pushing until finally—he succeeds.” 32

Prior to giving the speech, Fraser had talked with two of his teachers about the content of the address. Despite the fact that both teachers warned Fraser that his speech was “inappropriate,” Fraser nevertheless delivered the address at the assembly. A school counselor observing the assembly noticed an immediate reaction from the student audience as Fraser began to speak. According to the counselor, some students began yelling and hooting as Fraser delivered his sexual metaphor, while others simulated sexual acts through the use of graphic body gestures. In addition, the counselor noticed a number of students who seemed noticeably embarrassed and bewildered by Fraser’s blatant references to sexual activities.

33

!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

30 Bethel School District No. 403 v. Fraser , 478 U.S. 675, 677 (1986). The facts of this case were based on Jerry C. Chiang, “Plainly Offensive Babel: An Analytical Framework for Regulating Plainly Offensive Speech in Public Schools, Washington Law Review 82

(May 2007), 403; and Curtis G. Bentley, “Student Speech in Public Schools: A

Comprehensive Analytical Framework Based on the Role of Public Schools in

Democratic Education,” Brigham Young University Education and Law Journal 2009

(2009), 1.

!

31 478 U.S. 675, 678 (1986).

!

32 Fraser v. Bethel School District No. 403 , 755 F.2d 1356, 1357 (9

!

33 478 U.S. 675, 678 (1986). th Cir. 1985).

15

The day after his delivery of the nomination speech, Mr. Fraser was called into the Assistant Principal’s office and told that his speech was in violation of a disciplinary rule within Bethel High School. The rule the Assistant Principal was referring to stated that any action which “materially and substantially interferes with the educational process is prohibited, including the use of obscene, profane language or gestures.” Upon admitting that he had deliberately included sexual metaphors in his nominating speech,

Fraser was suspended for three days and removed from the list of students eligible to speak during the school’s commencement festivities.

34

Following the student’s return to school, Fraser’s father filed a lawsuit in the

United States District Court for the Western District of Washington, alleging the violation of his son’s First Amendment rights. The District Court found in favor of

Fraser and determined that Bethel school officials did indeed violate the student’s constitutional right to freedom of expression.

35

Bethel administrators appealed this decision to the Court of Appeals for the Ninth

Circuit. The Ninth Circuit in turn affirmed the ruling of the District Court. In ruling in favor of Fraser, the court looked at the Tinker standard and concluded that, “the Bethel

School District…failed to carry its burden of demonstrating that Fraser’s use of sexual innuendo in the nominating speech substantially disrupted or materially interfered in any way with the educational process.” 36 The Ninth Circuit also struck down the contention

!

!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

34 478 U.S. 675, 678 (1986).

!

35 478 U.S. 675, 679(1986).

!

!

36 Fraser v. Bethel School District No. 403 , 755 F.2d 1356, 1359 (9 th Cir. 1985).

16

!

of Bethel officials that they have a right to forbid the expression of “indecent” language within the school environment. Indeed, the court held that when dealing with students at the high school level, such a right is far too ambiguous and overly broad. The court expressed its fear that “if school officials had the unbridled discretion to apply a standard as subjective and elusive as ‘indecency’… it would increase the risk of cementing white, middle-class standards for determining what is acceptable and proper speech and behavior in our public schools.” 37

The Bethel school district appealed this decision to the Supreme Court, which granted certiorari and agreed to consider the case. In writing the majority opinion for the case, Chief Justice Burger sided with administrators and created an entirely new category of unprotected student expression. Indeed, while recognizing the point made in Tinker that students do have First Amendment rights in the learning environment, Chief Justice

Burger made certain to draw a clear distinguishing line between the political armbands in

Tinker and the sexually charged nomination speech given by Fraser.

38 Indeed, in critiquing the decision made by the Ninth Circuit, Chief Justice Burger noted that the

“marked distinction between the political ‘message’ of the armbands in Tinker and the sexual content of respondent’s speech in this case seems to have been given little weight by the Court of Appeals.” 39 Chief Justice Burger went on to opine that while the armbands in Tinker were a form of silent protest aimed at one of the most controversial military endeavors in American history, Fraser’s speech amounted to “lewd,

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

37

!

38

755 F.2d 1356, 1363 (9 th Cir. 1985).

478 U.S. 675, 680(1986).

!

!

39 478 U.S. 675, 680(1986).

17

!

indecent…(and) offensive speech,” expression of a much less worthy kind than that displayed in Tinker .

40

In framing his argument, Chief Justice Burger first made note of the fact that the

First Amendment rights afforded to students are not the same as those afforded to adults in greater society. Indeed, Chief Justice Burger emphasized this fact by citing the prior

Supreme Court case New Jersey v. T.L.O.

, in which the Supreme Court justices held that a student’s Constitutional rights in the public learning environment are not coextensive with the rights of adult American citizens.

41 In order to justify this viewpoint, Chief

Justice Burger depicted the public school as a unique environment. The Chief Justice explained that public school administrators have a unique duty to fulfill, in that they must teach students the boundaries of socially acceptable behavior. Indeed, administrators must ready students to become American citizens by teaching them “manners of civility.”

According to Chief Justice Burger, it is these manners that form the backbone of a happy and active democratic society.

42

Chief Justice Burger went on to say that the use of vulgar and offensive terms by students presents a grave threat to the necessary teaching of these “manners of civility” by school administrators. Indeed, the allowance of lewd speech within the school environment sends the wrong message to students with regard to how civilized people should behave. According to Chief Justice Burger, administrators serve as role models for their students, and through their ignorance in the face of student vulgarity, they send

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

40 478 U.S. 675, 683 (1986).

!

41 478 U.S. 675, 682 (1986).

!

!

42 478 U.S. 675, 681 (1986).

18

the message that this type of lewd speech is wholly appropriate within greater society.

43

In actuality, this type of speech goes against the core values that form the heart of

America’s democratic system. For, as the Chief Justice points out, while these democratic values include the ability to speak differing opinions freely, the use of vulgar terms takes away from any intelligent discussion and does not serve to further any

American value of civility.

44 Consequently, it is necessary for administrators to set a good example for their students and forbid the use of vulgar and offensive terms in the learning environment.

Chief Justice Burger also made certain to note the danger vulgar language poses to young children. The Chief Justice pointed out that in acting as parental figures during the school day, administrators have a duty to protect young students from exposure to

“sexually explicit, indecent, or lewd speech.” 45 For this type of language is simply not appropriate for young students. In support of this claim, Chief Justice Burger cited the

Supreme Court case Ginsberg v. New York .

46 In this decision, the Supreme Court upheld a state statute forbidding the sale of sexual material to minors.

47 By citing this case,

Justice Burger was clearly attempting to show that the Supreme Court has a history of protecting young children from inappropriate sexual content.

!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

43 478 U.S. 675, 683 (1986).

!

44 478 U.S. 675, 683 (1986).

!

45 478 U.S. 675, 684 (1986).

!

!

46 Ginsberg v. New York , 390 U.S. 629 (1968).

!

47 390 U.S. 633 (1968).

19

!

Keeping in mind the pressing need to keep vulgar and obscene language out of the school environment, Chief Justice Burger determined that the First Amendment did not protect Fraser’s nominating speech. In reaching this conclusion, Chief Justice Burger cited the blatant sexual innuendo present in the address. The Chief Justice also stressed the offensive nature of the speech, stating that the crude and graphic celebration of male sexuality was particularly insulting to the young girls present during the assembly. In addition, the Chief Justice took into consideration the fact that many in the assembly audience were a mere 14 years of age, meaning that they were only on the “threshold of awareness” regarding human sexuality. Chief Justice Burger was clearly disturbed by the possible consequences Fraser’s explicit speech could have on the sexually developing minds of these young pupils.

48 Based on the vulgar nature of the speech and the age of the audience members present for its deliverance, Chief Justice Burger concluded that

Fraser’s mode of expression was not protected under the First Amendment.

In constructing this majority opinion, Chief Justice Burger paid very little attention to the precedence set by Justice Fortas in Tinker . In considering Fraser’s speech, Chief Justice Burger could have applied Tinker ’s “substantial disruption” test and considered whether the nominating address was disruptive enough to the school environment. Instead, Chief Justice Burger chose to add to the limitations outlined in

Tinker and create an entirely new category of unprotected student expression: that speech which is vulgar, lewd, and offensive.

And so, with this decision, the scope of student speech worthy of First

Amendment protection was significantly reduced. This new limitation involving vulgar

!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

48 478 U.S. 675, 683 (1986).

20

speech, along with those exceptions articulated in Tinker , served as the Supreme Court standard for student speech for over twenty years following Bethel . However, in 2007, the Supreme Court once again ruled on the matter of “pure speech” in the public school environment. Much like Bethel , this new case, Morse v. Frederick , served to limit the scope of First Amendment protection afforded to students. Indeed, with Morse , the

Supreme Court created yet another major limitation on student speech rights.

Morse : Court Strikes Down Drug Speech

The circumstances surrounding Morse took place in Juneau, Alaska on the eve of the 2002 Winter Olympic Ceremonies. The torch relay that preceded the Olympic ceremonies was scheduled to pass by Juneau Douglas High School on January 24, 2002.

The relay was expected to proceed in front of the educational institution during the school day, and as a result, the Principal of the high school, Ms. Deborah Morse, elected to make an activity out of the event. Indeed, Principal Morse decided to allow students to participate in the relay as part of an “approved social event or class trip.” Students were permitted to watch the relay from both sides of the street in front of the school, while administrators were stationed amongst the students in order to monitor behavior.

49

!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

49 Morse v. Frederick , 551 U.S. 393, 397 (2007). The facts of this case are based on

Angie Fox, “Waiting to Exhale: How ‘Bong Hits 4 Jesus’ Reduces Breathing Space for

Student Speakers & Alters the Constitutional Limits on Schools’ Disciplinary Actions

Against Student Threats in the Light of Morse v. Frederick ,” Georgia State University

Law Review 25 (Winter 2008), 435; and Mark W. Cordes, “Making Sense of High School

Speech After Morse v. Frederick ,” William and Mary Bill of Rights Journal 17 (March

!

2009), 657.

21

Late to school that day was a Juneau Douglas senior by the name of Joseph

Frederick, who arrived at school just in time for the passing of the torch. Rather than checking in with attendance however, Frederick immediately went to join his friends observing the relay from the street. Upon the arrival of the torchbearers and television crews, Frederick and his surrounding friends displayed a 14-foot banner with the words,

“BONG HiTS 4 JESUS” written across it.

50 Since the banner was so large, it was easily spotted by Principal Morse, who immediately went over to Frederick and demanded that it be taken down. Frederick refused to comply with the order, and was subsequently suspended for ten days.

51 In upholding Frederick’s suspension, the Juneau School

District Superintendent held that the banner was “inconsistent with the school’s educational mission to educate students about the dangers of illegal drugs and to discourage their use.” 52

Following this decision by the Superintendent, Frederick filed a lawsuit in the

United States District Court for the District of Alaska, alleging the violation of his First

Amendment rights. The District Court determined that Morse and the school board had not violated Frederick’s First Amendment rights by forcibly removing the banner. The court appealed to the standard set by Fraser in support of their holding. First, the court chose to read Fraser as not just a standard permitting the censorship of vulgar speech, but also as a standard that allows school boards to “‘determine what manner of speech…is

!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

50 551 U.S. 393, 397 (2007).

!

51 551 U.S. 393, 398 (2007).

!

!

52 551 U.S. 393, 399 (2007).

22

!

inappropriate.’” 53 The court also read Fraser as a case that allows for the censorship of student speech that “might undermine the school’s basic educational mission…” 54 The court then determined that Morse was qualified to censor Frederick’s pro-drug banner, considering the fact that the Juneau School District “determined that messages advocating illegal drug use undermine its own mission.” 55 Indeed, the District Court held that “Morse had the authority, if not the obligation, to stop such messages at a schoolsanctioned activity so as not to place the imprimatur of school approval on the message.” 56

Following this decision, Frederick appealed his case to the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. After reviewing the facts, the Ninth Circuit chose to reverse the ruling of the District Court and side with Frederick. In justifying this outcome, the Ninth

Circuit used the Tinker standard rather than the Fraser standard used by the District

Court. The Ninth Circuit, in following with a very narrow interpretation of Fraser , reasoned that Frederick’s speech was very different from that struck down in Fraser , seeing as Frederick’s banner was “not sexual, and did not disrupt a school assembly.” 57

Seeing as the banner was not analogous to the speech in Fraser , the Ninth Circuit decided to analyze Frederick’s speech under the Tinker standard. According to this standard, Morse would have to demonstrate that the banner was likely to cause

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

53 Frederick v. Morse , 2003 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 27270, 20 (D. Ala. 2003).

!

54 2003 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 27270, 20 (D. Ala. 2003).

!

55 2003 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 27270, 20 (D. Ala. 2003).

!

!

56 2003 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 27270, 20 (D. Ala. 2003).

!

57 Frederick v. Morse , 439 F.3d 1114, 1119 (9 th Cir. 2006).

23

“substantial disruption” within the school environment in order to justify the censoring of the speech. The Ninth Circuit concluded that the school failed to put forth such evidence, noting that school officials “conceded that the speech in this case was censored only because it conflicted with the school’s ‘mission’ of discouraging drug use.” 58

Consequently, the court concluded that Frederick’s banner did not fall into one of the censorable categories within the Tinker standard, and was thereby protected expression under the First Amendment.

Following this ruling by the Ninth Circuit, Morse appealed to the Supreme Court, which granted certiorari. Chief Justice Roberts, in writing for the majority, reversed the decision of the Ninth Circuit and ruled in favor of Morse. In so doing, Chief Justice

Roberts, like Chief Justice Burger in Fraser , went beyond an application of the Tinker standard and created an entirely new category of unprotected student expression. Chief

Justice Roberts first contended that Frederick’s banner amounted to a pro-drug message.

Indeed, Chief Justice Roberts noted the banner’s “undeniable reference to illegal drugs,” while concluding that the message on the banner had to mean either “Take bong hits” or that “bong hits are a good thing.” 59

Chief Justice Roberts then built upon two major legacies that arose from Justice

Burger’s opinion in Fraser . First, Chief Justice Roberts emphasized Chief Justice

Burger’s proclamation in Fraser that the First Amendment rights of students are not coextensive with the rights of adults in larger society.

60 In addition, Chief Justice Roberts

!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

58

!

59

439 F.3d 1114, 1123 (9 th Cir. 2006).

551 U.S. 393, 402 (2007).

!

60 551 U.S. 393, 404 (2007).

24

pointed out the fact that Chief Justice Burger did not use a Tinker analysis in declaring

Fraser’s nomination speech void of First Amendment protection.

61 By mentioning this,

Chief Justice Roberts laid the groundwork for the creation of his own category of unprotected student expression.

Of course, this new category that Chief Justice Roberts was attempting to create consisted of student speech that promoted the use of illegal drugs. In an effort to add a great deal of backing to his argument, Chief Justice Roberts included a plethora of evidence concerning the dangers of illegal drug use by school children. Calling the need to deter drug use by students an “‘important—indeed, perhaps compelling’ interest,”

Chief Justice Roberts cited the Supreme Court case Vernonia School District 47J v.

Acton , in which the justices proclaimed that drugs can have especially devastating effects on young people, impairing their nervous systems and causing them to become chemically dependent very quickly. Chief Justice Roberts also made certain to note the widespread presence of illegal drugs within the student population, citing statistics that put the number of high school seniors who have tried any illegal drug at approximately fifty percent.

62

Keeping in mind the fact that the First Amendment rights of students are not on par with those of adults, in addition to the compelling need to stop the prevalence of teenage drug usage, Chief Justice Roberts determined that Frederick’s banner was unworthy of constitutional protection. In doing so, Chief Justice Roberts created yet

!

!

!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

61 551 U.S. 393, 405 (2007).

!

62 551 U.S. 393, 407 (2007).

25

another category of student speech outside the reach of the First Amendment: that speech which promotes the use of illegal drugs. This new category, in combination with Chief

Justice Burger’s category concerning lewd speech and Tinker ’s two exceptions to student expression, has served to severely reduce the amount of “pure” student speech protected within the public school environment.

In Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District , the Supreme

Court affirmed the reality of the First Amendment within the public school system.

Indeed, Justice Fortas held that students are citizens with constitutional rights, even inside the classroom. However, the Court in Tinker also held that the First Amendment rights afforded to students are not as extensive as those constitutional rights afforded to adults.

Expanding upon this notion, the Court outlined two major limitations to student speech rights within the educational environment. First, the Court stated that any student speech that serves as a “substantial disruption” within the school environment is not deserving of

First Amendment protection. Secondly, the Court noted that any student expression that collides with the “rights of other students to be secure and to be let alone” is also not worthy of constitutional protection.

63 These two exceptions served as the only limitations on student speech rights until Fraser , when the Court determined that “lewd, indecent…(and) offensive speech” was also not worthy of First Amendment protection within the school environment. In 2007, the Supreme Court added one final category of unprotected student speech to the picture, declaring in Morse that any student speech that promotes the use of illegal drugs is not to be afforded First Amendment protection.

!

!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

63 393 U.S. 503, 508 (1969).

26

!

The limitations outlined in these three cases currently determine the constitutionality of all instances of “pure” student speech within America’s public school system. However, there is a second branch of student speech case law that deals with another type of expression: school-sponsored student speech. While pupils engaging in

“pure” student speech receive no assistance from their public schools, students engaging in school-sponsored speech express themselves through school-sponsored mediums. The landmark Supreme Court case within this branch is Hazelwood School District v.

Kuhlmeier . Unlike the landmark Tinker case within the “pure” student speech branch,

Hazelwood does not recognize the reality of the First Amendment within the educational environment. Indeed, within this branch, school authorities are given great reign to censor instances of expression.

School-Sponsored Student Speech

Hazelwood : “Legitimate Pedagogical Concerns”

This case centered on a group of students who attended Hazelwood East High

School in St. Louis County, Missouri. This group of students served as staff members for a school-sponsored newspaper known as the Spectrum . Students enrolled in Hazelwood

East High School’s Journalism II class carried out the writing and editing for this school newspaper. Over 4,000 copies of the paper were distributed throughout the student body and the greater Hazelwood community approximately every three weeks. Funds to pay for the printing of the newspaper came primarily out of the Hazelwood Board of

27

Education’s budget, although revenue from newspaper sales did cover a portion of the printing expenses.

64 In addition, the Board of Education also covered additional costs rung up by the newspaper, including textbooks, writing supplies, and part of the annual salary given to the journalism teacher.

65

On May 10, 1983, Mr. Howard Emerson, the man teaching Journalism II at

Hazelwood East High School, handed over the proofs of the upcoming addition of the

Spectrum to the Principal of East Hazelwood, as was customary to do prior to each printing. The Principal, Mr. Robert Reynolds, was not pleased with two of the articles that were scheduled for inclusion in the newspaper. One of the articles concerned three students’ experiences with teen pregnancy, while the second story concerned the impact of parental divorce on Hazelwood East High students. In terms of the teen pregnancy story, Principal Reynolds was extremely concerned that the identities of the pregnant students would surface and that younger Hazelwood students would be prematurely exposed to discussion about sexual behavior and methods of contraception. In terms of the story on divorce, Principal Reynolds was of the belief that the feuding parents mentioned in the story should have been given the chance to address the claims made in

!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

64 Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier , 484 U.S. 260, 262 (1988). The facts of this case are based on Walter E. Forehand, “Tinkering with Tinker : Academic Freedom in the

Public Schools: Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier ,” Florida State University Law

Review 16 (Spring 1988), 159; and Jeffrey D. Smith, “High School Newspapers and the

Public Forum Doctrine: Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier ,” Virginia Law Review

!

!

74 (May 1988), 843.

65 484 U.S. 260, 263 (1988).

28

!

the article, or at the very least been given the chance to consent or object to the story’s publication.

66

Due to the fact that he wanted to get the newspaper out prior to the end of the school year, Principal Reynolds made the decision not to wait for changes to be made to the two articles in question. Rather, the Principal decided to remove the two pages from the newspaper that contained the inappropriate articles and send the rest of the newspaper to the press at the regularly scheduled time.

Upon learning about the deletions made to the newspaper, several students from the Journalism II class opted to draw up a lawsuit against the school district in the United

States District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri, alleging a violation of their First

Amendment rights.

67 In ruling in favor of the school district, the court identified the presence of the school-sponsored category of speech, noting that within this branch of case law, “the interests of school officials and the special function performed by schools in our society are given considerably more weight” than would be given in instances of

“pure” expression.

68 The court went on to hold that since the Spectrum was “an integral part of Hazelwood East’s curriculum,” a great deal of discretion was to be afforded to school officials in terms of censoring articles.

69 Considering the censorship committed by Mr. Reynolds was done out of the reasonable concern that the anonymity of the students mentioned in the articles would be lost, the court determined that the removal of

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

66 484 U.S. 260, 263 (1988).

!

67 484 U.S. 260, 264 (1988).

!

!

68 Kuhlmeier v. Hazelwood School District , 607 F. Supp. 1450, 1463 (E.D. Mo. 1985).

!

69 607 F. Supp. 1450, 1465 (E.D. Mo. 1985).

29

!

the articles did not in fact violate the First Amendment rights of the Hazelwood students.

70

The students appealed this decision to the Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit.

The Eight Circuit in turn reversed the decision of the District Court and sided with the students. Indeed, the Eighth Circuit reasoned that rather than serve as merely a part of the school curriculum, the Spectrum was “a (public) forum in which the school encouraged students to express their views to the entire student body freely…” 71 Having declared the newspaper a public forum, the court then went on to apply the Tinker “pure” speech standard to the facts of the case. In doing so, the court determined that there was

“no evidence in the record that the principal could have reasonably forecast that the censored articles or any materials in the censored articles would have materially disrupted classwork or given rise to substantial disorder in the school.” 72 Hence, the censoring of the speech was deemed a violation of the students’ First Amendment rights.

Following this decision, the Hazelwood school district appealed their case to the

Supreme Court, which granted certiorari. In writing the majority opinion for the Court,

Justice White first broke with the Eighth Circuit and determined that the Spectrum was not equivalent to a “public forum.” Indeed, the Justice reasoned that a school-sponsored newspaper did not have the same qualities as a traditional forum for public discourse, such as a street or a park. Rather, the newspaper, as part of the Hazelwood curriculum, was meant to serve an educational purpose. Justice White cited the Hazelwood East

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

70 607 F. Supp. 1450, 1466 (E.D. Mo. 1985).

!

71 Kuhlmeier v. Hazelwood School District , 795 F.2d 1368, 1373 (8 th Cir. 1986).

!

!

72 795 F.2d 1368, 1375 (8 th Cir. 1986).

30

!

Curriculum Guide in making the claim that the writing of the Spectrum in the Journalism

II class was meant to serve as a practical exercise in “applying skills…learned in

Journalism I.” Justice White further emphasized the school-sponsored nature of the newspaper by pointing out that the Journalism II teacher had a great deal of editorial control over the newspaper, determining everything from the selection of the editors to the number of pages for each issue.

73 Indeed, while Hazelwood administrators allowed students a degree of control concerning the content of the newspaper, the main purpose of the newspaper, as was stated in the school’s Curriculum Guide, was to teach students

“leadership responsibilities as issue and page editors.” As was argued by Justice White, the purpose of the newspaper was not to set up a “public forum” for discussion within the school.

74

Justice White then went on to make a broader point about school-sponsored student expression. While the Justice admitted that school administrators must tolerate a certain amount of student speech, he went on to state that this does not mean administrators have to affirmatively promote instances of student speech by forgoing all censorship in mediums associated with the school. Indeed, Justice White held that with regard to publications sponsored by the school and all other activities that “students, parents, and members of the public might reasonably perceive to bear the imprimatur of the school,” administrators have a great deal of censorship power.

75 Indeed, the Justice contended that so long as the censorship of the school-sponsored expression is

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

73 484 U.S. 260, 268 (1988).

!

74 484 U.S. 260, 270 (1988).

!

!

75 484 U.S. 260, 271 (1988).

31

!

“reasonably related to legitimate pedagogical concerns,” school administrators are not to be held in violation of their students’ First Amendment rights.

76 Justice White reasoned that with this holding, administrators could be assured that their students were taking away from their school-sponsored activities what they were supposed to be learning, that young students were not being subjected to inappropriate material, and that the views of students were not “erroneously attributed to the school.” 77

The Legacy of Hazelwood

While Justice White was commenting upon school-sponsored speech within the public high school environment in his Hazelwood majority opinion, a number of cases in the years since Hazelwood have considered the question of whether Justice White’s holding applies to public universities and colleges as well. Justice White made no effort to stretch the reach of his decision to the post-secondary level. Indeed, the Supreme

Court in Hazelwood made it clear that it was only discussing First Amendment rights in the public high school environment, stating, “we (the Supreme Court) need not now decide whether the same degree of deference is appropriate with respect to schoolsponsored expressive activities at the college and university level.” 78 In the years since

Hazelwood , however, federal appellate courts have been faced with the decision of whether to apply the Hazelwood standard to colleges and universities.

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

76 484 U.S. 260, 273 (1988).

!

77 484 U.S. 260, 271 (1988).

!

!

78 484 U.S. 260, 273 (1988).

32

!

In some instances, federal appellate court judges have sided with college students and rendered Hazelwood inapplicable in the post-secondary environment. In the case of

Kincaid v. Gibson , judges for the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals did just this. This case involved several students at Kentucky State University and a yearbook known as The

Thorobred . In an effort to bring a new, unique face to this yearbook, the KSU student editor of the yearbook for the 1993-1994 academic year decided to make the book cover purple and give the yearbook a theme for the first time ever. The theme chosen was

“destination unknown,” a tribute to the perceived uncertainty of the time period. In addition, the editor also decided to include a current events section that covered both national and global events.

79

Upon viewing the yearbook make-over, the Vice President for Student Affairs at

KSU, a woman by the name of Betty Gibson, determined that the book was unfit to be distributed to the student body. Gibson was extremely unhappy with the purple book cover, seeing as the school colors for KSU were green and gold. Additionally, Gibson had problems with the theme of the book, the lack of photo captions, and the presence of the “current events” section. Due to these problems, Vice President Gibson concluded that the yearbook was unfit for distribution. As a result, the printed books were immediately confiscated and locked away within the KSU campus.

80

Following this confiscation, students filed a free speech lawsuit in the United

States District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky at Frankfort. In siding with the

University, the court chose to apply the Hazelwood standard within the collegiate setting.

!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

79 Kincaid v. Gibson , 236 F.3d 342, 345 (6 th Cir. 2001).

!

80 236 F.3d 342, 345 (6 th Cir. 2001).

33

Indeed, the court determined that the yearbook was a “nonpublic forum” and that “KSU officials’ actions were reasonable” according to Hazelwood precedent.

81 Hence, the confiscation of the yearbooks was not, according to the district court, a violation of any

First Amendment rights.

Following this ruling, the students appealed their case to the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. Once there, the judges for the Sixth Circuit determined that Vice

President Gibson had indeed violated the students’ First Amendment rights by confiscating the yearbook. Indeed, according to the judges for the Court of Appeals, the yearbook served as a “limited public forum” within the KSU community and was thereby to be given heightened First Amendment protection. To support this holding, the judges referenced KSU’s student handbook, as well as the actions of school administrators in dealing with the yearbook. First, the judges pointed out that the student handbook put full editorial control of the yearbook in the hands of university students.

82 Secondly, the judges noted that administrators took an extremely “hands-off” approach in terms of inquiring about the content of the yearbook. Indeed, the student editor of the book testified that Vice President Gibson “‘never expressed any concern about what the content might be in the yearbook.’” 83 Based on these facts, the Sixth Circuit judges concluded that the KSU yearbook was indeed a “limited public forum” whose content was to be decided by university students. Deeming the actions of Vice President Gibson

!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

81

!

82

236 F.3d 342, 346 (6 th Cir. 2001).

!

236 F.3d 342, 349 (6 th Cir. 2001).

!

83 236 F.3d 342, 351 (6 th Cir. 2001).

34

!

“arbitrary and unreasonable,” the Sixth Circuit determined that the confiscation of the yearbook had amounted to a violation of the KSU students’ First Amendment rights.

84

Along with their labeling of the yearbook as a “limited public forum,” the Sixth

Circuit judges also paid special attention to the broader issue of the importance of First

Amendment rights in the collegiate setting. In writing the majority opinion for the Court of Appeals, Judge Guy Cole Jr. pointed out that the “danger of ‘chilling…individual thought and expression’” is particularly real in the college setting. Judge Cole went on to label the college environment the “quintessential ‘marketplace of ideas,’” a place deserving of special attention when it comes to First Amendment protection.

85 With the inclusion of these thoughts, Judge Cole effectively made the argument that Hazelwood precedence has no bearing within the sophisticated marketplace of the collegiate environment.

While the Sixth Circuit in Kincaid determined that the Hazelwood standard had no bearing within the collegiate environment, other federal appellate courts have been more willing to apply this student speech standard to university settings. Indeed, in Hosty v. Carter , the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals took the road opposite that of the Sixth

Circuit and deemed the Hazelwood decision completely applicable within the university setting. This case concerned students at Governors State University, as well as a college newspaper known as the Innovator .

86 The trouble began when student journalist

Margaret Hosty wrote an article attacking the integrity of the Dean of the College of Arts

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

84

!

85

236 F.3d 342, 357 (6 th Cir. 2001).

!

236 F.3d 342, 352 (6 th Cir. 2001).

!

86 Hosty v. Carter , 412 F.3d 731, 732 (7 th Cir. 2005).

35

and Sciences, Mr. Roger Oden. When Mr. Oden and University President Stuart Fagan accused the student writers of engaging in irresponsible journalism, the students remained one hundred percent behind their stories, refusing to retract any facts or even print the statements written by Mr. Oden or Mr. Fagan. In light of this behavior on the part of the students, Patricia Carter, Dean of Student Affairs and Services, gave the order that no more editions of the Innovator were to be printed until she had had the chance to review and approve the issues. Unwilling to cooperate with this new system of prior approval, the student writers sued the Dean of Student Affairs, citing a violation of their First

Amendment rights.

87

In writing the majority opinion for the Hosty case, Seventh Circuit Judge

Easterbrook held that the Hazelwood opinion was indeed applicable to school-sponsored publications at the collegiate level. In support of this assertion, Judge Easterbrook pointed out that nowhere in the Ha z elwood opinion did Justice White hint at the presence of an “on/off switch,” in which administrators could edit high school newspapers but never college newspapers.

88 In addition, the Seventh Circuit judge asserted that the question of age was not relevant in determining whether or not Hazelwood applies at the collegiate level. The judge pointed out that the age line between high school seniors and college freshmen is extremely blurry.

89 Indeed, Judge Easterbrook went to great lengths to blur even the line between secondary and collegiate publications, noting that there

!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

87

!

88

412 F.3d 731, 733 (7 th Cir. 2005).

!

412 F.3d 731, 734 (7 th Cir. 2005).

!

89 412 F.3d 731, 734 (7 th Cir. 2005).

36

!

really is “no sharp difference between high school and college papers.” 90 Based on these assessments, Judge Easterbrook concluded that the Hazelwood standard was indeed deserving of a place within the university environment.

In Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier , the Supreme Court set the standard by which all instances of school-sponsored expression within the public high school environment were to be measured. This standard placed a great deal of discretion within the hands of school administrators in terms of being able to censor student speech.

Indeed, the Court reasoned that so long as the censorship was “reasonably related to legitimate pedagogical concerns,” school administrators would not act in violation of students’ First Amendment rights.

91 Due to the fact that the Court did not discuss at all the applicability of this standard to the collegiate setting, federal appellate courts have had to determine for themselves whether this standard was meant to apply only within the high school environment. Some courts have held that the standard has no bearing on expression made by college students, while other courts have determined that the standard is meant to apply within the university setting.

The Tinker, Fraser , and Morse “pure” speech cases, along with the Hazelwood school-sponsored speech case, encompass the current body of law that determines the constitutionality of student speech within the public school environment. In deciding current student speech cases, federal judges look to these cases to apply the appropriate precedent and determine the correct outcome. Indeed, both the District Court for the

Southern District of California and the Ninth Circuit, in considering the case Harper v.

!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

90

!

91

412 F.3d 731, 735 (7 th Cir. 2005).

484 U.S. 260, 273 (1988).

37

Poway Unified School District , looked to these Supreme Court cases for guidance and appropriate standards. However, while both looked at the same Supreme Court cases, the two courts came to different conclusions as to what standard to apply to Harper .

Harper v. Poway Unified School District

District Court Decision

In reviewing the facts of the Harper case, the District Court for the Southern

District of California determined that Tyler Harper’s t-shirt should be looked at through the lens of the Tinker decision. While the court considered analyzing Harper’s shirt using a Fraser analysis, the judges ultimately determined that there was not enough evidence to support the contention that the anti-homosexual phrases were “plainly offensive.” 92

However, the District Court did see merit in using a Tinker mode of analysis.

In particular, the District Court focused on the first major exception to student speech rights as outlined by Justice Fortas in determining whether Harper’s First

Amendment rights had been violated. This was the exception that stated that any speech that “materially disrupts classwork or involves substantial disorder” is not to receive First

Amendment protection.

93 In addition to referencing this line from Tinker , the District

Court made clear the fact that under Tinker, school administrators are not required to wait

!

!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

92 Harper v. Poway Unified School District , 345 F. Supp. 2d 1096, 1120 (S.D. Cal. 2004).

!

93 393 U.S. 503, 513 (1969).

38

for disruption to occur. Rather, administrators are permitted to censor student speech in the presence of facts that reasonably forecast material disruption.

94

Upon reviewing the evidence provided by the Poway School District, Judge John

A. Houston determined that Harper’s t-shirt did indeed lead school officials to reasonably forecast substantial disruption. In coming to this conclusion, the District Court took into account the conflict that erupted during the 2003 “Day of Silence” at Poway High

School, as well as Mr. LeMaster’s testimony that Harper’s t-shirt caused a “disruption” during class time. The District Court also pointed to Principal Fisher’s testimony that

Harper had engaged in a “‘tense verbal conversation with a group of students’” while on school grounds as reason to forecast substantial future disturbance.

95 Based on these facts, the District Court concluded that Harper’s t-shirt fell within the first major exception to student speech rights as outlined in the Tinker opinion.

Following this decision by the District Court, Tyler Harper and his counsel chose to bring their case to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. The Ninth Circuit agreed to take the case and examine the facts surrounding the anti-homosexual t-shirt. While the facts remained the same from when the District Court took the case, the Ninth Circuit used a slightly different mode of analysis in determining whether Harper’s First

Amendment rights had been violated.

!

!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

94 345 F. Supp. 2d 1096, 1120 (S.D. Cal. 2004).

!

95 345 F. Supp. 2d 1096, 1120 (S.D. Cal. 2004).

39

!

Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Decision

Upon examining the facts of the Harper case, the Ninth Circuit first determined that the shirt needed to be analyzed using a Tinker mode of analysis.

96 However, the

Ninth Circuit did not follow the lead of the District Court and view Harper’s t-shirt through the lens of Tinker ’s first exception to student speech rights. Rather, the Ninth

Circuit focused on the second exception to students’ expressive rights outlined in the

Tinker opinion. This exception stated that any speech made by a student that “collides with the rights of other students to be secure and to be let alone” is not deserving of First

Amendment protection.

97 In addition to referencing this portion of Tinker , the Ninth

Circuit made sure to note that another student’s rights might be violated absent any actual physical confrontation. The Ninth Circuit also made certain to point out that the speech in question need not directly refer to any individual student in order to qualify as an invasion of the rights of a particular pupil.

98

Under this mindset, the Ninth Circuit concluded that Harper’s t-shirt did indeed interfere with the rights of other pupils. The Ninth Circuit viewed the shirt as a blatant attack on certain students within the Poway community based solely on their sexual orientation. The Ninth Circuit considered this type of attack unacceptable, stating,

“students who may be injured by verbal assaults on the basis of a core identifying characteristic such as race, religion, or sexual orientation, have a right to be free from

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

96

!

97

445 F.3d 1166, 1177 (9 th Cir. 2006).

393 U.S. 503, 508 (1969).

!

!

98 445 F.3d 1166, 1178 (9 th Cir. 2006).

40

!

such attacks.” Indeed, the Ninth Circuit stressed the importance of a student’s right to be left in peace and insisted that the public school setting was not a place where students could “hide behind the First Amendment” in an effort to intimidate and verbally assault their peers.

99

In an effort to support this holding, the Ninth Circuit offered a great deal of evidence as to the harmful effects verbal assaults have on homosexual students. Indeed, the Ninth Circuit pointed to the writings of Susanne Stronski, whose research shows that

“academic underachievement, truancy, and dropout are prevalent among homosexual youth.” Ms. Stronski contends that these trends are most likely the consequences of verbal and physical attacks within the learning environment.

100 The Ninth Circuit also referenced additional studies, one of which claimed that homosexual students struggle to concentrate in school out of a fear for safety, while another study put the dropout rate of homosexual teens at triple the national average for all teenage dropouts.

101 Given these studies, the Ninth Circuit concluded that Harper’s t-shirt presented a true threat to the learning abilities and psychological health of homosexual students within Poway High

School. Consequently, the Ninth Circuit dismissed Tyler Harper’s First Amendment claim based on the fact that the anti-homosexual shirt fell within the second exception to student speech rights as outlined in the Tinker majority opinion.

Following this decision by the Ninth Circuit, Harper appealed his case to the

Supreme Court. However, the Supreme Court denied certiorari. To the surprise of many