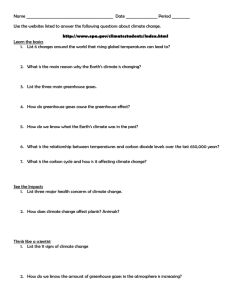

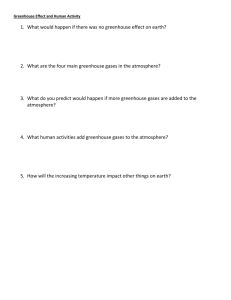

Document 11206723

advertisement