(1974) THE KINETICS OF HYDRODEMETALLATION METALLOPORPHYRINS BY

advertisement

THE KINETICS OF HYDRODEMETALLATION

OF

METALLOPORPHYRINS

BY

CHI-WEN HUNG

B. Ch. E., National Taiwan University

(1974)

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

August, 1979

-I

signature of Author

Department of Chemical Engineering

August, 1979

Certified by

James Wei, Thesis Supervisor

Accepted by

G. C. Williams, Chairman, Departmental

Committee on Graduate Thesis

ARCHIVES

OF

2i:cf ncY

LIBRARIES

THE KINETICS OF HYDRODEMETALLATION

OF

METALLOPORPHYRINS

BY

CHI-WEN HUNG

Submitted to the Department of Chemical Engineering

on August

3

1979 in partial fulfillment of the

,

requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy.

ABSTRACT

The kinetics of hydrodemetallation of nickel etioporphyrin I (Ni-Etio),

nickel tetraphenylporphine

(Ni-TPP), and vanadyl etioporphyrin I (VO-Etio)

have been studied in batch autoclave experiments, with white oils as

solvents, and CoO -MoO 3 /Al 2 03 as catalyst without presulfiding.

The effects of hydrogen pressure up to 12-500 KPa and temperature

between 287-357 C were studied.

Up to 90% metal removal,

described by fractional order kinetics.

the data can be

The activation energy is from

27-37 kcal/g mole, and the hydrogen pressure dependence is from 1.2-2.2

order.

Vanadium removal tends to have larger activation energy and smaller

hydrogen pressure dependence.

A few runs on mixed vanadyl and nickel etioporphyrins showed that

while the presence of vanadyl compounds will suppress the nickel removal

reaction,

the reverse is

less significant.

Few runs on free base etio-

porphyrin and tetraphenylporphine show that free base porphyrins quickly

disappear in the autoclave.

Catalyst with different propotion of cobalt and molybdenum have

been prepared to catalyze nickel etioporphyrin as reactants.

The result

.shows that order of impregnation has no effect on hydrodemetallation

activity, and MoO 3/Al

Thesis Supervisor:

2

0 3 catalyst is

more active than CoO/Al 2 0 3 catalyst.

James Wei

Professor and Department Head

of Chemical Engineering

ACKNOW:EDGEMENTS

I would like to express my appreciation and gratitude to my

advisor, Dr. James Wei, for the guidance and support given to me

over these years.

The useful discussion with Drs. Putnam,

Satterfield, and

Vayenas of the M.I.T. Chemical Engineering Department, and Dr. Peter

Hambright of Howard University are greatly appreciated.

My colleague, Rakesh Agrawal, has been of invaluable help to me.

I would also like to thank my friends for their helping hands and

advice regarding my research.

Cocchetto,

Among them are Kelvin Chew, Joe

Selahattin Gultekin, George Huff Jr., Jen-Jiang Lee, and

Cherng-Chiao Wu.

This work is dedicated to my parents, Dr. and Mrs. Tsu-Pei Hung,

and especially to my wife, Shu-Fang, for her assistance in typing the

manuscript and for her understanding and compassion.

-5TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

1.

INTRODUCTION

18

2.

BACKGROUND AND LITERATURE SURVEY

21

2.1

Metal Compounds in Petroleum

2.1-1

2.1-2

2.1-3

2.2

3.

24

2.1-1.a

Porphyrins

24

2.1-1.b

Metalloporphyrins

27

Geochemistry of Porphyrins

35

35

2.1-2.a

Types of Porphyrins in Petroleum

2.1-2.b

Origin of Porphyrin and Metalloporphyrin

Nonporphyrin Metal Compounds

37

40

Hydrodemetallation Reaction

45

2.2-1

46

2.2-2

2.3

Properties of Porphyrins and Metalloporphyrins

21

Kinetics

2.2-1.a

Thermal Demetallation and Nonhydrogenative Demetallation

46

2.2-1.b

Hydrodemetallation

48

Deposition of Metals on Hydrodesulphurization

Catalysts

58

2.2-2.a

Concentration Distribution of Vanadium

and Nickel on Spent Catalysts

58

2.2-2.b

Amount of Deposition

61

2.2-2.c

Catalyst Aging

62

2.2-2.d

Distribution along the Reactor Bed

64

Research and Development on Metal Removal Processes

MATERIALS AND EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

66

69

3.1

Equipment for Hydrodemetallation Study

69

3.2

Materials

77

3.2-1

Catalyst

77

3.2-2

Solvent

85

3.2-3

Gas

85

3.2-4

Model Porphyrins and Metalloporphyrin; Com-pounds

87

-6Table of Contents (cont'd)

3.3

3.4

Experimental Procedures

90

3.3-1

Dissolving Model Compounds in Nujol

90

3.3-2

Pretreatment of Catalyst

94

3.3-3

Demetallation Experiment

94

3.3-4

Self Preparation Catalyst

98

101

Analysis

3.4-1

Liquid Sample

101

3.4-2

Solid Sample

107

3.4-3

Gas Sample

107

109

4. RESULTS

4.1

Page

Nickel Porphyrin Runs for Commercially Available HDS 9A

109

or HDS 16A Catalyst

4.1-1

4.1-2

4.2

Air Prepared Ni-TPP Runs

109

4.1-l.a

General Observations

109

4.1-1.b

Kinetics

112

4.1-1.c

Catalyst Effects

117

Helium Prepared Nickel Porphyrin Runs

124

4.1-2.a

General Observations

124

4.1-2.b

Kinetic Order

129

4.1-2.c

Catalyst Effects

135

Vanadyl Porphyrin Runs

140

4.2-1

General Observations for VO-Etio Runs

140

4.2-2

Kinetic Order

144

4.2-3

Catalyst Effects

148

4.3

Free Base Porphyrin Runs

149

4.4

Mixed Nickel and Vanadyl Porphyrin Runs

152

4.4-1

General Observations

152

4.4-2

Kinetics

152

-7Page

Table of Contents (cont'd)

4.5

5.

162

Self Preparation Catalyst Runs

4.5-1

General Observations

162

4.5-2

Effect of Cobalt or Molybdenum on Demetallation

Activity of Ni-Etio

166

170

DISCUSSION OF RESULTS

5.1

170

Diffusion Effects

5.1-1

Nickel Porphyrin Runs

170

5.1-2

Vanadyl Porphyrin Runs

174

5.1-3

Mixed Ni-Etio and VO-Etio Runs

175

5.2

Hydrogen Consumption

178

5.3

Intermediates and Products in Liquid Phase

180

5.3-1

Intermediates

180

5.3-2

Products

189

5.4

5.5

192

Intermediatea and Products on Catalyst

5-4-1

Intermediates

192

5.4-2

Products

192

Discussion on Kinetic Model and Possible Mechanism

19

5.5-1

Background

199

5.5-2

Results and Discussion

205

5.6

Catalyst Deactivation

218

5.7

Comparison among Nickel Runs

219

5.7-1

Between Air Prepared Ni-TPP and Helium Prepared

219

Nickel Porphyrin Runs

5.7-2

Comparison between Helium Prepared Ni-TPP and

220

Ni-Etio Runs

5.7-3

5.8

5.9

Comparison between CoO-MoO3 /A

Catalysts for Ni-Etio Runs

2 03

and NiO-MoO /Al 2 0

223

Comparison between Nickel and Vanadyl Porphyrin Runs

227

Comparison between Individual Ni-Etio, VO-Etio Runs

229

and Mixed Ni-Etio, VO-Etio Runs

-8Table of Contents (cont'd)

6.

Page

5.10

Comparison with Previous Work

231

5.11

Differentiating between Two First-Order Reactions and

a Single Second-Order Reaction

235

CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS

247

6.1

Conclusions

247

6.2

Suggestions

250

7.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

252'

8.

NOMENCLATURE

266

APPENDIX

Experimental Data

268

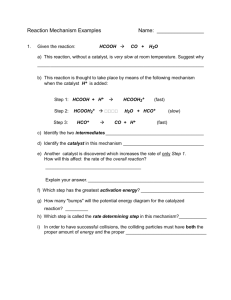

-9LIST OF FIGURES

Number

Title

Page

2-1

Nomenclature of Porphyrin System

25

2-2

The UV-Visible Absorption Spectrum (in CH Cl 2 ) of Etioporphyrin-I and DPEP (Deoxophylloerythroe ioporphyrin).

(Alturki et al. (1971)).

28

2-3

Visible Spectra of Porphyrins: (a)

30

-Phylloporphyrin

XV;

(b) Etioporphyrin I; (c) Rhodoporphyrin XV; (d) Deoxophylloerythroetioporphyrin. (Baker et al. (1978)).

2-4

Absorption Spectra for DPEP (Deoxophylloerythroetioporphyrin) Type of Vanadyl Porphyrin (Top),

Porphyrin (Bottom).

33

and Nickel

The curves that show Soret band

peaks have been diluted from the others that show visible

peaks.

(Hodgson, et al. (1967)).

2-5

Absorption Spectra for Nickel Etioporphyrin I (Top) and

Vanadyl Etioporphyrin I (Bottom).

Samples were Dissolved

in Nujol First and Then Diluted by Xylene. Background:

Xylene.

34

2-6

Scheme for The Transformation of Chlorophyll Qk to Stable

Vanadyl Porphyrins.

38

2-7

41

Examples for Nonporphyrin Metal Compounds: (1) Highly

Aromatic Porphyrin Chelates; (2) Porphyrin Decomposition

Ligands, (Metals will Fill Up to the Center); and (3) Simple

Complexes from Resin Molecules. (Yen (1975)-(a)).

2-8

Cross Sectional View of an Asphaltene Model.

2-9

Defect Site in an Aromatic Sheet of the Asphaltene

Structure. (Yen (1974)).

2-10

Qualitative Changes in Asphaltenes and Surrounding

49

Resins During HDS Processing. (Beuther and Schmid (1963)).

2-11

Sulphur Removal Versus Nickel Removal and Vanadium

Removal for Several Vacuum Gas Oil.

(Yen (1977)). 43

43

56

(Massagutov et al.

(1967)).

2-12

Concentration Profile of Vanadium and Nickel on the

Desulphurization Catalyst after 50hrs Reaction.

(Sato et al. (1971))

60

-10-

List of Figures (cont'd)

Title

Number

Page

2-13

Concentration Profile of Carbon, Vanadium, and Nickel

(Sato et al. (1970)).

Along with the Reactor Bed.

65

3-1

Schematic of High Pressure Autoclave Reactor System for

Hydrodemetallation Study.

70

3-2

Autoclave Batch Reactor System.

71

3-3

List of Components for Figure 3-2.

72

3-4

Schematic of Main Body of 1-Liter Autoclave.

73

3-5

Schematic of Catalyst Loader and Porous Filter.

75

3-6

Pore Size Distribution for HDS-16A CoO-MoO 3 /Al 2 03

Catalyst.

80

3-7

Pore Size Distribution for HDS-9A Ni0-Mo0 /Al 2 03

82

Catalyst.

3-8

Pore Size Distribution for VI-Alumina Catalyst Carrier.

84

3-9

Structure of Model Compounds: (1) TPP; (2) Etio-I;

(3) Ni-TPP; (4) Ni-Etio I; (5) VO-TPP; (6) VO-Etio I.

88

3-10

Structures of Chlorins (TPP type).

89

3-11

Apparatus for Removing Air from Nujol.

92

3-12

Apparatus for Dissolving Model Compounds in Nujol.

93

3-13

Absorption Spectra of Ni-TPP and VO-TPP.. Samples were

Dissolved in Nujol First and then Diluted by Xylene.

Background: Xylene.

103

3-14

Absorption Spectra of Free Base Etio I and Free Base TPP.

Samples were Dissolved- in Nujol First and then Diluted by

Xylene. Background: Xylene.

104

-11-

List of Figures (cont'd)

Title

Number

Page

3-15

Soxhlet Extraction Apparatus.

108

4-1

Dependence of Noncatalytic Disappearance of Air Prepared

Ni-TPP on the Operating Temperature.

113

4-2

First 'Order Plot for Air Prepared Ni-TPP Run (Run NT4).

114

4-3

First Order Plot for Air Prepared Ni-TPP Run (Run NT6).

115

4-4

Arrhenius Plot for Air Prepared Ni-TPP Runs.

118

(6995 1Pa

Hydrogen, Oil/Catalyst=650 cc/g).

4-5

Effect of Catalyst on Air Prepared Ni-TPP Hydrodemetallation Reaction.

119

4-6

The Dependence of First Order Rate Constant in Fast

121

Reaction Region on the Oil/Catalyst Ratio. (Run NT6-

NT9).

4-7

The Relationship between the Amount of Nickel Deposited

122

on the Catalyst when the Shift from Fast Region to Slow

Reaction Region Occurs and the Oil/Catalyst Ratio.

4-8

(a) Zero Order Plot; (b) First Order Plot; (c) Second

Order Plot; (d) Half Order Plot for Run NEY4.

130

4-9

Effect of Temperature on Half Order Rate Constants for

Nickel Porphyrin Disappearance Rate. P: 6995 IPa

H2'

133

4-10

Effect of Temperature on Half Order Rate Constants for

Total Nickel Removal Rate. P: 6995 KPa H2'

134

4-11

Pressure Dependence of Half Order Rate Constants.

T: 3160C. (Ni-Etio Runs).

136

4-12

Comparison between Hydrodemetallation (NEll) and Nonhydrogenative Demetallation (NE16H) Reaction.

137

4-13

Effect of Catalyst on Hydrodemetallation Reaction.

139

-12List of Figures (cont'd)

4-14

Page

Title

Number

Comparison of Vanadium and Nickel Runs (Run VE8 and

142

Run NE18) over Alumina Support.

4-15

Comparison of Vanadium and Nickel Runs (Run VE9H, NE16H,

143

and NT18H) under Helium Pressure.

4-16

Half Order Plot for VO-Etio Run.

4-17

Effect of Temperature on Half Order Rate Constants for

VO-Etio Runs.

4-18

(Run VE3).

145

P: 6995 KPa.

Pressure Dependence of Half Order Rate Constants for

VO-Etio Runs.

146

147

T: 316 0 C.

4-19

Half Order Plot for Mixed VO-Etio and Ni-Etio Run. (Run

NVE5).

154

4-20

Half Order Plot for Mixed VO-Etio and Ni-Etio Run. (Run

156

NVE3).

4-21

Dependence of Half Order Rate Constants on the Ratio

of Ni-Etio and VO-Etio Initial Concentrations.

157

T:316 C;

P: 6995 KPa.

4-22

Absorption Spectra of Mixed VO-Etio and Ni-Etio Run.

(Run NVE2). Top: Fresh Sample. Bottom: Sample Collected

1.6 hrs after Injection of Catalyst. All were Diluted

by Xylene.

158

4-23

Effect of Temperature on Half Order Rate Constants for

Mixed VO-Etio and Ni-Etio Runs. P: 6995 KPa; C /CNo

2.12.

159

4-24

Pressure Dependence of Half Order Rate Constants in Mixed

Ni-Etio and V-Etio Runs. T: 316 C; C vo/CNio: 2.11.

161

4-25

Effect of Molybdenum on Half Order Rate Constants of

167

Ni-Etio Runs.

4-26

Dependence of Half Order Rate Constants on Cobalt Addition

for Ni-Etio Runs.

168

-13List of Figures (cont'd)

5-1

Page

Title

Number

Scanning Electron X-Ray Microanalyzer Indication of

Nickel Distribution for Spent Catalyst of Run NT25,

172

and Fresh Catalyst.

5-2

Weight Percent of Nickel Deposited on the Designated

Spots of the Catalyst Pellet Described in Figure 5-1.

173

5-3

Scanning Electron X-Ray Microanalyzer Indication of

Vanadium Distribution for Spent Catalysts of Run VE3,

176

and Run VT1.

5-4

5-5

Weight Percent of Vanadium Deposited on the Designated

Spots of the Catalyst Pellets Described in Figure 5-3.

177

Indication of Intermediates (Run NE14): (Left): Plot

181

of Concentration Difference between Total Nickel and

(

Ni-Etio -Versus Time. (Right): Plot of Absorption

Arbitary Unit) of 6 16nm Peak Versus Time.

5-6

Absorption Spectrum of Ni-TPP and Ni-Etio During Reaction. 182

For Run NT20, and NE14.

5-7

Absorption Spectrum of VO-TPP and VO-Etio During Reaction. 184

For Run VT1 , and VE3.

5-8

Color Pictures of Ni-Etio Sample (NE14), and VO-Etio

Sample (VE3).

185

5-9

Color Pictures of Ni-TPP Sample (NT15), and VO-TPP

Sample (VT3).

186

5-10

Temperature Dependence of k, K1 , and Kp for Ni-Etio Runs.

206

5-11

Temperature Dependence of k, K 1 , and Kp for VO-Etio Runs.

207

5-12

Experimental and Theoretical Concentration Versus Time

Data for Run NE4.

209

5-13

Experimental and Theoretical Concentration Versus Time

Data for Run VE3.

210

5-14

Comparison between Experimental Data and Theoretical

Values of Spent Oil Run. (NE15).

215

-14-

List of Figures (cont'd)

Title

Number

Page

5-15

Comparison between Air Prepared Ni-TPP Run (NT6) and

Helium Prepared Ni-TPP Run (NT20).

222

5-16

The Range of Parameter Values of A and B Suitable for

239

Two First Order Kinetics to Simulate Second Order

Kinetics, and the Dependence on Conversion Level.

5-17

The Range of Parameter Values of A and B Suitable for

Two First Order Kinetics to Simulate Second Order

Kinetics, and the Dependence on Conversion Level.

240

(In Log-Log Scale).

5-18

The Dependence of~b(Minimum of

m

) and A on E (Con-

241

version).

5-19

The Dependence of B and kN on E (Conversion).

242

5-20

Comparison between Concentration D, Obeying Second

Order Kinetics, and Two First Order Kinetics, Cf and C

244

-15LIST OF TABLES

Number

Title

Page

2-1

Distribution of Trace Elements in Components of

California Crude Oil. (Filby, (1975)).

22

2-2

Distribution of Nickel and Nickel Porphyrin.in Crude

Oil Fractions. (Filby, (1975)).

23

2-3

Structures of Selective Porphyrins of The Four Basic

29

Types. (Baker and Palmer (1978)).

2-4)

Molecular Weight of Homologues Series of Porphyrins.

36

2-5

Kinetic Order, Activation Energy, and Rate Constants

for Thermal Demetallation of Vanadium and Nickel in

Residual or Crude Oils.

47

2-6

Summary of Previous Studies on Kinetics of Catalytic

52

Hydrodemetallation.

3-1

List of Major Components in Figure 3-4.

74

3-2

Physical and Chemical Properties for American Cyanamid

79

HDS 16A CoO-MoO3 /Al 2 03 Catalyst.

3-3

Physical and Chemical Properties for American Cyanamid

HDS 9A NiO-MoO3 /Al 2 03 Catalyst.

81

3-4

Physical and Chemical Properties for Norton SA-6273

83

Alumina Catalyst Carrier.

3-5

Specifications of Nujol.

86

3-6

Operating Conditions for Demetallation Experiments.

97

3-7

Absorption Peaks for Model Compounds.

105

3-8

Peaks Used for Quantitative Analysis.

105

4-1

Operating Conditions for Air Prepared Ni-TPP Runs.

110

-16List of Tables (cont'd)

Page

Title

Number

4-2

Operating Conditions for Each Nickel Rune

125

4-3

Reproducibility of Nickel Runs.

128

4-4

Dependence of Kinetic Order on Temperature and

Pressure.

132

4-5

Operating Conditions for Each Vanadium Run.

141

4-6

Operating Conditions for Free Base Porphyrin Runs.

150

4-7

Operating Conditions for for Mixed VO-Etio and Ni-Etio

153

Runs.

4-8

Composition of Self Preparation Catalysts.

163

4-9

Operating Conditions for Self Preparation Catalyst Runs.

164

4-10

Comparison between Self Preparation Catalysts and

Commercial Catalysts on Hydrodemetallation Activity

of Ni-Etio.

165

5-1

Duration of Each Sample Shown in Figure 5-8 and Figure

187

5-9.

5-2

Concentration of C, H, N, V, and Ni on Spent Catalysts

of Different Runs.

194

5-3

Metal

Rate Values (R ) as a Function of Initial

Initial

Concentration or Hydrogen Pressure for Ni-Etio Runs.

211

5-4

Initial

Rate Values (R

0

)

as a Function of Initial

Metal

213

Concentration or Hydrogen Pressure for VO-Etio Runs.

5-5

Comparison of Pseudo First Order Rate Constants of Air

Prepared Ni-TPP and Helium Prepared Ni-TPP Hydrodemetallation Runs.

221

5-6

Comparison between VO-Etio, Ni-Etio, and Ni-TPP Demetallation Runs.

225

-17List of Tables (cont'd)

Number

5-7

5-8

Title

Page

Comparison between CoO-MoO /Al

Catalysts for Ni-Etio Runs

2

03 and NiO-Mo0 /Al2 03

230

Comparison between Individual Ni-Etio, VO-Etio, and

Mixed Ni-Etio, VO-Etio Runs.

226

(Total Metal Removal).

5-9

Comparison of First Order Demetallation Rate Constants

between Previous Literature and This Study.

5-10

Values of A, B,0 , and K

version).

for a Given Value of G

(

Con-

232

243

-

1.

18-

Introduction:

Due to the shortage of crude oil supply, there has been a rapid

expansion in demand for upgrading residual oils in the past few years.

This tendency is expected to be continued in the years to come.

(Penick (1977),

Johnson et al. (1975)).

Although nearly half of the elements in the periodic table have

been identified in crude oils (Smith et al. (1959)),

are commonly the most abundant metals.

distillation,

substantially all

section (Nelson (1976)).

nickel and vanadium

During atmospheric or vacuum

of the metals are left

in the residual

The concentration of vanadium plus nickel in

residual oils ranges from less than 10 ppm (Such as Murban Crude) to

more than 1700 ppm (Boscan Crude from Venezuela), commonly they are

within the range of 30 to 200 ppm (Nelson (1976)).

With few exceptions,

there appears to be more vanadium than nickel in the residual oils.

(Yen (1975)-(a)).

As the presence of these vanadium and nickel compounds will cause

many problems during upgrading or burning of residual oils, they have to

be removed:

(1)

The metal compounds will react with hydrogen at the presence of

hydrodesulphurization (HDS)

(HDM) reaction.

catalyst in the so-called hydrodemetallation

The final metal sulfides will deposit on the catalyst

and deactivate the HDS catalyst.

While the initial deactivation of

-19-

HDS catalyst is due to coke deposition which can be removed by com-

bustion; the ultimate life of the catalyst is primarily controlled by

the irreversible deposition of metals.

(1975),

and McColgan and Parsons,

(Brunn et al. (1975), Newson

(1974)).

This results in higher

catalyst replacement rate, larger reactors, and higher temperature of

HDS operation (Hastings et al.

(1975)).

In addition to these, higher

hydrogen pressure, lower space velocities, and higher hydrogen recycle

rates are also required (Billon et al. (1977)).

Based on the price

of $1.20/lb for Co-Mo HDS catalyst, the catalyst cost increase from as

low as 4#/bbl for low-metal feeds to as high as 400/bbl for medium-metal

(150

ppm vanadium plus nickel) feeds; it

is

usually not feasible to

desulphurize the residual oils that contain more than 200 ppm of vanadium

plus nickel due to the catalyst cost (Nelson (1976)).

The higher

hydrogen consumption for high metal content residual oils has also being

metioned by Nelson (1977).

(2) When desulfurized residual oils are sent to cracking unit for further

upgrading to make gasoline or kerrosene, the left over metals will

deposit on and deactivate the cracking catalyst (Ritter et al. (1974)).

The deposted metals will increase hydrogen, lights gas, coke yields,

and decrease the gasoline yield; nickel in the charge caused 4.5 times

the increase in coke yield, and

7.9 times the decrease in gasoline

yield as did an equal amount of vanadium in the charge.

(Dale and

-20-

Mckay (1977),

Habib et al. (1977),

and Donaldson et al. (1961)).

An

example given by Edison et al. (1976) shows that for a 50,000 b/d

Cat cracker with 50 ppm vanadium plus nickel in the feed, about

40 tons/day of fresh catalyst must be added to prevent the metal level

from exceeding 1%.

(3) During combustion of these hydrotreated residual oils, the metals

will form ashes in combustion; while nickel oxide will have erosion

effect, the vanadium oxide will have corrosion effect to the furnace

linings and turbine blades.

(4) If trace amounts of oxides of vanadium and nickel escape to the

atmosphere during combustion, they will be harmful to humans, animals,

and plants (Smith (1975)).

A better understanding of the hydrodemetallation reaction and the

laws of metal deposition would lead to better designs of catalysts and

reactors, and to longer economic life of the catalyst.

As in residual oils, there are many metal compounds of unspecified

nature and quantity; also, sulphur compounds, nitrogen compounds, and

asphaltenes are available.

All these species will make the study of

hydrodemetallation difficult.

This study used pure model metal compounds

of known structure dissolve in white oil, so that kinetics of hydrodemetallation can be studied for each compound individually.

By this

way, the kinetic result will not be affected by other metal compounds,

sulphur compounds, and other materials commonly occuring in residual

oils.

-212.

2.1

Background and Literature Survey:

Metal Compounds in Petroleum:

Metal compounds in petroleum are usually been placed into two

categories, metalloporphyrins and nonporphyrin metal compounds.

As

the study of porphyrins can contribute to broaden our knowledge about

the origin and history of petroleum, the metalloporphyrins have been

studied extensively in the past.

have not been well characterized.

The nonporphyrin metal compounds,

The ratio of metalloporphyrins to

nonporphyrin metal compounds varies from 0.01 to 1, depends on the

source of crude oils.

(Dean and Whitehead (1963), Costantinides and

Guido (1963),Baker (1978),

Hodgson et al. (1963)).

The distribution

of vanadium and nickel in crude oils is determined by separating the

crude oils into three compounds: (1)

Methanol soluble fraction, (2)

Resin: methanol insoluble and n-pentane soluble, and (3) Asphaltenes:

n-pentane insoluble.

Table 2-1 (Filby (1975))

shows the distribution

of several trace metals in different fractions of California crude

oils, Table 2-2 shows the distribution of nickel and nickel porphyrin

in different fractions.

It appears that most of the metals (especially

nonporphyrin metal compounds) occur in the asphaltene fraction.

The vanadium present in crude oils has been shown to exist entirely

+2

in the vanadyl state (V=0)+2.

nickel appears to be Ni+2

(Yen (1977), and Saraceno et al. (1961));

-22-

Table 2-1:

Distribution of Trace Elements in Components of California Crude Oil.

(Filby, (1975))

Concentration

9,g/g)

rude oil(%)

Crude Oil

Methanol

Soluble

100.0

57.5

Resins

37.5

Asphaltenes

R

C

A

C

4.99

v

7.5

0.82

12.4

61.6

1.65

8.2

Ni

93.5

7.21

147.0

852.0

1.57

9.1

Co

12.7

0.8

10.7

122.0

0.84

9.6

Fe

73.1

1.95

66.4

895.0

0.91

12.2

Hg

21.2

0.686

29.6

140.0

1.40

6.6

1.41

11.9

0.95

11.7

Cr

o.634

0.300

0.894

Zn

9.32

0.74

8.86

Sb

0.0517

0.0033

0.0130

1.22

0.25

23.6

As

0.656

0.546

0.290

2.25

0.44

3.4

7.540

109.

R ratio of metal concentration in resins to that in crude

-d=

ratio of metal concentration in asphaltenes to that in crude

-23-

Table 2-2:

.

Distribution of Nickel and Nickel Porphyrin in Crude-Oil Fractions,

(Filby, (1975))

Fraction

Crude Oil

Methanol Soluble

Resins

Asphaltenes

57.5

37.5

4.99

1.590

0.123

2.500

14.500

Ni.

Porphyrin

(pmol/g)

1.050

0.142

1-60o

7.130

Ni as Ni

Porphyrin

66.o

100.0

64.0

49.2

34.0

0

36.0

51.8

Crude Oil

100.0

(%)

Ni

Concentration

(Amol/g)

(%)

Nonporphyrin

Ni (%)

-24-

Properties of Porphyrins and Metalloporphyrins:

2.1-1

There are two books that deal with porphyrins and metalloporphyrins

and are of great value in this study: (1)

Vol VII, by Dolphin D. (1978),

"The Porphyrins", Vol I to

and (2) "Porphyrins and Metallopor-

phyrins", by Smith K.M. (1975).

2.1-1.a

Porphyrins:

The compound formed from four pyrrole groups linked via the c(-

positions through four methine groups is known as

which is the basic skeleton of porphyrins.

porphine,

(C

20

H

N

Porphyrins have various

substituents replacing the pyrrolic hydrogens

(position 1-8),

the

methine hydrogens (ok, P, 9 and 6 positions), or the imine hydrogens.

Other parent macrocycles are chlorin, phorbin, tetrahydroporphyrin with

opposite rings reduced is called bacteriochlorin, and hexahydropor-

phyrin (called porphyrinogen).

Figure 2-1.

Porphine

All these structures are shown in

itself does not occur in nature, but porphyrins

are found in nature both in the free form and as complexes with iron

(hematins, hematin enzymes such as the cytochromes, hemoglobin).

Substituted dihydroporphyrins called chlorins occur in the photosynthetic pigment, chlorophyll.

Due to its

stable.

This is

highly aromatic character, porphyrin ring is very

one of the reasons why they are of interest to

geochemists.

The most obvious physical property of porphyrins is

their intense

color which shows absorption bands in the visible and ultraviolet range.

-25-

6

/

NN

N

N

NH

N

6

N

HN

N

NN

5/

Porphin

Phlorin

N

-N

H

H

N

H

H

N

N f-N

Phorbin

Fig. 2-1 Nomenclature of Porphyrin System.

Chiorin-Phiorin

-26(Continued)

NH

/N

HH/

N/w

N

H

H/

N

N

N

Dihyroporphyrin

Dihydroporphyrin

/

(Chlorin)

\N HHN

NN

H

Bacteriochlorin

(Tetrahydrochlorin)

Fig.2-1

H-

Porphyrinogen

(Hexahydroporphyrin)

Nomenclature of Porphyrin System.

-27The molar extinction coefficients range from 100 to about 5 x 105.

The

The spectra can be separated into two parts, visible and near UV.

free-base porphyrins have four bands in visible range, an other band

near UV is the largest peak, usually near 400 nm, and is called the

Soret band.

Some spectra of porphyrins are given in Figure 2-2.

(Alturki et al. (1972)).

There are four major types of porphyrins: (1)

throetioporphyrin) Type, (2) Etio Type,

DPEP (Deoxophylloery-

(3) Rhodo Type,

(4) Phyllo Type.

Table 2-3 shows the structures of selected porphyrins of the four types

(Baker and Palmer (1978)).

four types of porphyrins.

Figure 2-3 shows the visible spectra of the

(Baker and Palmer (1978)).

The peaks in the

visible region are numbered I-IV, beginning at the longest wavelength.

The differences in relative heights of the visible peaks are a function

of the type of side chain substitution of the molecule.

Take for

example, the order of peak heights for etio-type is IV>-III-II-I.

More

details about discussion of these four types of porphyrins can be found

in the aformentioned two books about porphyrins.

2.1-1.b

Metalloporphyrins:

The chelation of a metal ion by a porphyrin involves the incorporation of the metal ion into the center of the tetrapyrrole nucleus

with the simultaneous displacement of two protons from the secondary

(pyrrole type) nitrogen atoms. Porphyrins form tetradentate chelates of

the inner complex type; this with a divalent metal ion of the positive

charges on the metal ion are exactly compensated by the negative charges

-28-

-

w

ETIOPORPHYRIN

0.4

x4

z

30

I

622

4O

'A

0

VI)

399

*1,

DPEP

CIO

09

x64.

X11

:0

40

WAVELENGTH

Fig. 2-2

616

SSI0

(nm)

The UV-Visible Absorption Spectrum (in CH2 Cl 2 ) of Etioporphyrin-I (C: 167.5x1 o3) and DPEP (Deoxophylloerythroetioporphyrin) (e: 296.7x103).

(Alturki et al. (1971)).

-29Table 2-3:

Structures of Selective Porphyrins of the Four Basic Types. (Baker

et al. (1978)).

Rs

.

R,

R,

R,

NH

N

N

HN

R.

.

R

R,

R.

V

Substituentso

Compound

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

M

H

M

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

Rhodo

H

H

H

DPEP

H

H

H

DPEP

R3

R4

Rs.

M

M

M

E

M

M

. M

E

E

E

M

E

E

E

M

E

M

M

M

M

M

E

M

E

E

E

H

H

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

E

E

E

E

H

E

E

M

E

E

E

P

M

M

E

M

M

M

M

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

M

Rhodoporphyrin XV

M

E

M

E

M

C

P

M

Dcoxophylloerythrin methyl

ester

Deoxophylloerythroetioporphyrin

M

E

M

E

M

CH2 CH 2 PMe

M

M4

E

M

E

M

M

Etioporphyrin I

Etioporphyrin 1i

Etioporphyrin III

Etioporphyrin IV

y-Phylloporphyrin XV

Deuteroctioporphyrin II

a, y-Dimethyldeuteroctioporphyrin II

*M

=

CH 3 ; E

=

CH 2 CH 3 ; P

=

- CH 2CH,

E

CH2CH 2 COOH; me - methyl ester; C - COCH.

type

a

R2

R,

Spectral

y

R,

R

Etio

Etio

Etio

Etio

Phyllo

Etio

Phyllo

-4

-30-

a

1.6

b

1.6

1.4

1.4

1.2

1.0

1.2

1.0

0.8

0.8

0.6

0.6

60.4

x

0.2

0.4

02

I

I

I

I

I

- - 20

c 1.6

1.4

-

Q.

1.4

1.2

-

t.o

5.220

1.0

-

1.0

0.8

0.80.6

0.6-

0.4

0.4

0.2

0

I

I

I

I

I

500

530

560

590

620

6W

470

50

530

560

590

620

650

Wav' Ienglh, nm

Fig. 2-3

Visible Spectra of Porphyrins: (a) c-Phylloporphyrin XV;

(b) Etioporphyrin I; (c) Rhodoporphyrin XV; (d) Deoxophylloerythroetioporphyrin. ( Baker et al. (1978)).

-31on the porphyrin nucleus, so that in the absence of ionized substituents

on the porphyrin the resulting chelate has no net charge.

While the molecule can be regared for most purpose as essentially

planar, with a diameter of approximately 8.5

.

and a thickness of

approximately 4.7R, there are significant deviations from planarity.

Fleischer (1962) found that in respect to the plane formed by the four

methene bridge-carbon atoms, two of the pyrrole rings are tilted

and two downwards.

upwards

In the case of nickel porphyrins, nickel sits

in the

middle of porphyrin plane; for vanadyl porphyrins, x-ray diffraction

data shows that vanadium atom lies out of the basal plane of the ligand

macrocycle,

the distance between the vanadium atom and the ligand basal

plane ranges from 0.3-0.6A, (Yen (1975)).

As mentioned earlier, vanadyl

porphyrins always require vanadium atom to connect to an oxygen atom

whi ch is perpendicular to the porphyrin plane.

The UV/visible spectra of metalloporphyrins are different from free

base porphyrins, usually there exist only two bands in visible range in

addition to the Soret band.

It is believed that if

the complex is highly

stable the visible peak at longer wavelength (0( band) will be higher

than the peak at shorter wavelength (P band).

and

P

(Falk (1964)).

The 0(

bands for nickel etioporphyrin in neutral solvents are at 550

and 514

n with d/J

intensity ratio of about 3.

phylloerythroetioporphyrin (DPEP), the

For nickel deoxo-

/p ratio is about 2.0.

etioporphyrins have peaks at 570 and 531 nm with the 4/l

ratio for vanadyl DPEP is 1.3.

Vanadyl

ratio 2, the

The reason for vanadyl porphyrins to

shift to longer wavelengths and reduced a/e ratio are considered to be

-32due to the additional coordination with the oxygen to yield a pentacoordinate complex.

(Baker and Palmer (1978)).

Figure 2-4 shows the

visible spectra for vanadyl and nickel DPEP (Hodgson et al. (1967));

and Figure 2-5 shows the visible spectra for vanadyl and nickel

etioporphyrins I.

-33-

SI

400

I

500

700

600

WAVELENGTH- Ytm

z

0

I

400

I

I

700

500

600

WAVELENGTH- tyxv\

Fig. 2-4 Absorption Spectra for DPEP (Deoxophylloerythroetioporphyrin)

Type of Vanadyl Porphyrin (Top), and Nickel Porphyrin (Bottom).

The curves that show Soret band peaks have been diluted from the

others that show visible peaks.

(Hodgson, et al.

(1967)).

-34-

z

0

I-a.

0

V)

CO

391

0.6

553

0.4

0.2

517

0

400

520

460

WAVELENGTH

i

580

(nm)

I

I

I

I

Pure Vo Etio

.

08F-

407

z

0

571.5

P0.

0

0.4

(in

534

CO3

4

I

i

0

380

420

460

500

WAVELENGTH

Fig. 2-5

540

5Z0

620

(n m)

Absorption Spectra for Nickel Etioporphyrin I (Top) and

Vanadyl Etioporphyrin I (Bottom).

Samples Were Dissolved!

in Nujol First and Then Diluted by Xylene.

Xylene.

Background:

-352.1-2

Geochemistry of Porphyrins:

2.1-2.a

Types of Porphyrins in Petroleum:

Most of the studies made in the past regarding porphyrins in

petroleum were done on the free base porphyrins.

The reason is that

in general the position and intensity of the metalloporohyrin visible

absorption bands are much less sensitive to alterations by substituents than are the spectra of the free base porphyrins; acid extraction

(demetallation) is usually taken to covert metalloporphyrins

to free

base porphyrins before study.

Special method for isolation of metalloporphyrins from petroleum

has been developed, but tends to be laborious.

(Baker and Palmer

(1978)).

The two most important types of porphyrins found in petroleum

are DPEP and Etio types, generally there appears to be more DPEP than

Etio in petroleum..

Rhodo type of porphyrin has also been found.

(Yen (1975)-(a), Sugihara et al. (1970), Baker (1969), and Didyk et al.

(1975)-(a)).

All three types of porphyrins exist

methylene homologues.

as series of

(Dean and Whitehead (1963)).

Table 2-4 shows the molecular weights of homologues series of

porphyrins.'

The molecular weight range for free base porphyrins in

petroleum appear to be among 394 and 562, the weight average mass are

about 420-490 for different crudes.

(Baker and Palmer (1978)).

1w

Table 2-4

Molecular Weight of Homologues Series of Porphyrins

Vanadyl

DPEP series

Rhodo series

BenzDPEP

Nickel

DPEP series

DPEP + 56

310 + 14n

DPEP

series

308 + 14m

8

422

420

428

485

476

9

436

434

442

499

490

10

450

448

456-

513

504

11

464

462

470

527

518

12 b

478

476

484

541

532

13

492

490

498

555

546

14

506

504

512

569

560

15

520

518

526

583

574

16

534

532

540

597

588

Etio and Phyllo

series

n or m

DPEP + 65

456 + 14n

aNumber of methylene groups attached to the porphyrin nucleus.

bEtioporphyrin and DPEP have an equivalent of 12 methylene group substituents.

(Baker and Palmer (1978)).

0'

-37Moleular weight higher than the above range have also been found,

and porphyrin dimers, trimers were also found.

(Blumer and Rudrum

(1970)).

Porphyrins have also been found in other materials: Hodgson et

al. (1963)

and Alturki et al. (1971)

sands; Hodgson et al. (1968)

studied the porphyrins in oil

studied the porphyrins in soils,

and sedimentary rocks; Hodgson et al. (1967)

sediments,

also examined porphyrins

in oil sand, solid hydrocarbons (Gilsonite and Grahamite), oil shales,

rocks, and coal; porphyrins in sediments have also received attention

by Baker and Saith (1974),

(1961);

oil, oil

Baker et al. (1970),

and Blumer and Omenn

Morandi and Jensen (1966) compared the porphyrins in shale

shale and petroleum by absorption and mass spectroscopy; and

finally, porphyrins in meteorites have been studied by Hodgson and

Baker (1969).

2.1-2.b

Origin of Porphyrin and Metallo Porphyrin:

The oldest and by far the most popular explanation for the

existence of metals in petroleum is that proposed by Treibs (1936).

His theory assumes that porphyrins (and possibly non-porphyrins) are

derived from chlorophylls of aquatic life.

Treibs suggested a series

of chemical reactions that could account for this transformation.

After some additions and modifications, Yen (1973)

came up a scheme

for the transformation of chlorophyll to vanadyl DPEP and other stable

vanadyl chelates.

This scheme is

shown in Figure 2-6.

A similar

scheme starting from hemin and yielding etioporphyrins was also

-38CIHLOROPHYLL a

O4.CM

PHEOP*4YTIN as

a

PHEOPHORBIDE

H3

2

C.M

CA

M+

M

+

,

CAC3

C.H

+RON

M

M

C"4M

C414

0

Ito

C-

OOIO

0CM 3

-cmi-CM.C-C

1-0,- HOCC,64"

PHEOPORPHYRfN

C3C

og

1

c3

H

3

4

OZ

=0C

C

CM 3

C-2 5,3

4

'O

CM3

j:,\

CM 3

CM 3

\C

C4 N 2

CM

CH

-,

C2 M5

N4\

Fig. 2-6M SceefrTeTasomto0fClrpyld

Vanadyl Porphyrins.

\

CH

C 2 H5

CH37

C 6M 3

17

0+

CM 3

ms-a- NAPHTHYLPORPI{YRIN

CM 3

3

/-H

M

RHODO t(BENZOPORPHYRIN)

(

CH

C 2 MZ 4

Z 2 5 H2 M

N

+

,

CMH 5

C94

4,

COT4

-

ETIO (ETIOPORPHYRIN)

C~ 5

-4.

C

0.0

C'Oz

HS

C2 M

2P-0-Co

++\

H

2 4

OPEP

5

+

C"3

ICM

DEOXOPHYLLOERYTHRIN

CM

3

0

-CM

OR

~)

PIIYLLOERYTHRIN

3

.0

+XI

oSal

C

3fI

-39proposed by Treibs, but is now rejected based on the findings that

there are not enough hemin exists in aquatic life

to the etioporphyrins.

(Corwin (1959)).

to contribute

One important fact from

the aformentioned scheme is that the Etio type of porphyrins were

derived from DPEP type of porphyrins; it

of geothermal maturation.

(1973), and (1969)

actually became an indiactor

(Didyk et al. (1975)-(b)).

Yen (1975)-(a),

studied the correlation of the ratio of DPEP/Etio

to the depth of burial for a number of petroleum deposits.

The source of metals in porphyrins is

not conclusive.

Some

proposed that vanadyl and/or nickel chlorins exist in living organisms

and that petroleum porphyrins are derived directly from such biogenic

metal complexes.

(1970))

(Hodgson et al. (1967)).

Others (Sugihara et al.

claimed that vanadium in non-porphyrin complexes such as

asphaltenes were the source of vanadium in porphyrin.

mentioned about the source of nickel in porphyrins.

Few were

-40Nonporphyrin Metal Compounds:

2.1-3

The study of nonporphyrin metal compounds is very important as

(1)

For many crude oils, there appear to be more nonporphyrin metal

compounds than metalloporphyrins.

(2) It is believed that the metals

in metalloporphyrins came from nonporphyrin metal compounds.

(Sugihara et al. (1970)).

Yen (1975)-(a) classified nonporphyrin metals into the following

groups : (a) Chlorophyll o( and other hydroporphyrins,

(b) Highly

aromatic porphyrin chelates, (c) Porphyrin decomposition ligands,

(d) Transition metal complexes of tetradentate mixed ligands such

as V, Ni, Fe, Cu, Co, and Cr.

two parts,

the first

is

and the other part is

This can be further separated into

the simple complexes from resin molecules,

chelates from asphaltene sheets.

metallic compounds such as Hg, Sb, As.

(e)

O gano-

(f) Carboxylic acid salts

of the polar functional groups of resins, such as Mo and Ge.

Colloidal minerals, such as silica and Nacl.

are of importance.

(g)

Only (b), (c) and (d)

Figure 2-7 shows the example for the (b), (c),

and simple complexes from resin molecules of (d) types of nonporphyrin

metals.

The most important nonporphyrin metal compounds are the ones

appear in the asphaltene fraction.

The reasons are substantial

amount of metal compounds appear in this fraction (Table 2-2).

Crudes high in metals are high in asphaltenes, and 50-99% of them are

nonporphyrin metal compounds.

(Yen, et al. (1968)).

-41-

N

N

/v 0

N

N

(-1)

V

M

v

M

ON1HO

H HO

MN

/

M

y

p

Y

P

P

p

(2)

0

o

V-*-

0

jm. -Va

0

65,

Ni

L0Q

(3)

Fig. 2-7

Examples for Nonporphyrin Metal Compounds: (1) Highly Aro*matic Porphyrin Chelates; (2) Porphyrin Decomposition Ligands,

(Metals Will Fill Up to the Center); and (3) Simple Complexes

from Resin Molecules.

(Yen (1975)-(a)).

-42Asphaltenes contain highly condensed aromatic and heterocyclic

The

rings with oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur (Ball et al. (1959)).

asphaltene molecules associate in dilute solutions at low temperatures,

but dissociate at high temperatures.

The molecular weights of asphal-

tenes depend on the methods of measurement, they range from 1,000

to 500,000, Dickie and Yen

(1967) published the tabulation of methods

and results; they also proposed a macrostructure of asphaltene.

et al. (1961),

(1962),

Yen

(1970), (1974) studied the asphaltene in petro-

leum extensively by x-ray diffraction and electron spin resonance.

The conclusion is that asphaltenes exists as clusters of sheets,

each

sheet is made up of individual molecules of aromatics, paraffins,

naphthenics, macrocyclics, and heterocyclics, the bridges or links

can be cleaved under selective chemical or physical conditions.

Each sheet has a graphite-like aromatic plate with a diameter of 8-151,

connects to the other

type of aformentioned hydrocarbons.

distance between parallel plates is

3.55-3.7a,

The

and generally an average

cluster consists of 4-5 plates with an overall thickness of 14-28R.

One of the characteristics of the single sheet in asphaltenes is

that

they can stack one above the other, bound together either through

interactions of the polynuclear aromatic centers or through

heteroatoms in the sheets.

It is also possible that increase the

metal content will increase the tendency of the particles to associate

further.

(Dickie et al. (1969)).

model based on x-ray diffraction.

Figure 2-8 shows the asphaltene

(Yen (1977)).

-43Sheet

SLe

8-15E

dm 3.55 - 3.70 A

dy 5.5-6.0 A

L6 -14-28 A

Fig. 2-8

Cross Sectional View of an Asphaltene Model. (Yen (1977)).

/yAJ\M

Represents the Zig-Zag Configuration of a Saturated.

Carbon Chain or Loose Net Naphthenic Rings.

Represents the Edge of. Flat Sheets Condensed Aromatic Rings.

Fig. 2-9

Defect Site in an Aromatic Sheet of the Asphaltene

Structure., (Yen (1974)).

-44It

is

known that many of the aromatic portions of the sheets have

defective centers (gaps and holes), these defects are formed as a

result of the incomplete graphitization of benzenoid rings by donor

atoms such as N, S, and 0.

It

is

believed that these defective

centers are the coordination centers of metals.

the example of defect site for metals.

Figure 2-9 shows

(Yen (1974)).

Finally, one thing very interest is that Sugihara et al. (1970)

mentioned that crudes with high vanadium content are high in sulfur,

and crudes with high nickel content are high in nitrogen.

He further

mentioned that oxovanadium is known to prefer to coordinate to ligands

with the decreasing order of 0"S -N,

nickel.

which it

is

N -S

-0

for

2.2

Hydrodemetallation Reaction:

As in addition to metal compounds, sulphur and nitrogen compounds

are available in residual oils, hydrodemetallation (HDM) always occur

along with hydrodesulphurization (HDS)

and hydrodenitrogenation (HDN)

reaction during hydroprocessing of residual oils.

Riley (1978)

(1971),

mentioned that HDM is

Oxenreiter et al. (1972),

faster than HDN; Frost et al.

Oleck and Sherry (1977)

showed that

Audibert and Duhaut

HDS is

faster than HDM in typical HDS units.

(1970)

also reported that the ratio of vanadium removal to sulphur

removal decrease with space velocity.

The chemistry of hydrodemetallation reaction is

not well known,

but both hydrogen and catalyst are required for the reaction to occur.

As sulphur compounds are available in residual and catalyst were

presulphided in commerical runs, the final metallic products deposited

on the catalyst are beleived to be inorganic metal sulphides.

tings, et al. (1975),

(Has-

Dautzenberg et al. (1978), Newson (1975), and

Schuit and Gates (1973)).

Under commercial conditions, hydrodemetallation typically takes

place at 4000C (750 0F) and 14MPa (2000 psig) of hydrogen by using

Coo-Moo 3 /Al 2 03 as catalyst.

2.2-1

Kinetics:

2.2-l.a

Thermal Demetallation and Nonhydrogenative Demetallation:

Wooldle and Chandler (1952) mentioned that vanadium and nickel

are thermally stable up to 3700 C(700 0 F), and at temperatures

approaching 3700C, these molecules exert very small but significant

vapor pressures.

Hodgson and Baker (1957)

studied the thermal behavior

of vanadium, nickel, and porphyrin contents in McMurray crude oil

(Athabaska) in connection with their studies of the petroleum

maturation process.

Constantinides and Guido (1959)

examined the

thermal behavior of vanadium, nickel in Kuwait residual.

Thermal

degradation for both vanadul and nickel porphyrins from Wyoming

reduced crude has been investigated by Rosscup and Bowman- (1967).Hodgson (1973)

used the above literature for his discussion about

the geochemistry of porphyrins.

All of them reported that the thermal

decomposition of the metal compounds in oil obeys first order kinetics,

with activation energy from 43 to

57 kcal/g-mole.

Nonhydrogenative

demetallation was studied by Fischer et al. (1976) for Wilmington

Residual, Agha Jari residual, and San Joaquin residual at the presence

of manganese nodules.

As their results were consistent with previous

studies on thermal demetallation, they suggested that nonhydrogenative

demetallation with manganese nodules is of thermal and not of catalytic

character.

A summary from the above literature regarding the kinetic

order, activation energy, and rate constent is shown in Table 2-5.

-47Table 2-5

Kinetic Order, Activation Energy, and Rate Constants for Thermal

Demetallation of Vanadium and Nickel in Residual or Crude Oils:

Author

Kinetic

order

(1) Hodgson and

Baker (1957)

Activation

Energy (Kcal/g mole)

52.5

(Porphyrin )002

Degradation

58.6

(m

(Nickel)

Removal(38C

57.5

(2) Costantinides

et al.

Rate

Constant (1/hr)

1_

(Porphyrin

(1959)

Degradation

(3) R;sscup and

Bowman (1967)

(4) Fischer et al-

(1976)

45.6

0.013 (3580 C)

0.012 (3580 C)

0.41 (3900 C)

-Vanad-

0.068 (3900 C)

(Nickel

0.070 (39000)

Vanadium

Removal

46

)

(3580C)

( Nickel

0.21 (3900C)

0.12 (3900 C)

Vanadium

Removal

0.28 (3900C)

( Neoal)

0.23 (3900C)

2,2-1.b

Hydrodemetallation:

Beuther & Schmid (1963) studied the kinetics of vanadium and

nickel removal for Middle East (Kuwait) reduced crudes and found

that the kinetic order is second order with respect to metal compounds.

They also found that vanadium removal rate is faster than nickel

removal rate.

By using the structure of asphaltene proposed by

Yen et. al. (1961)

which has also been shown in Figure 2-8, they

postulated that nickel concentrates on the interior of the asphaltene

"molecule", while vanadium concentrates on the exterior of the

molecule.

This is

one of the reason they believed to be the faster

vanadium removal rate.

Another reason they believed is that the valence

state of vanadium ih vanadium complex is +4, while nickel is +2.

As

the vanadium does not have its valences satisfied in the basal plane,

it is also bound to an oxygen atom.perpendicular to the planer structure

of complex such as porphyrin.

The tendency of atoms to project from

the plane (see 2.1-1.b) for vanadium complexes may take the metal

atom more accessible to the catalyst through the projecting hetero-atom.

In another word, they believed that it is the polarity and accessibility

at the periphery of the asphaltene molecule that makes the ease of

vanadium removal relative to nickel.

Figure 2-10 shows their

description about the qualitative changes in asphaltenes during HDS

processing.

Larson and Beuther (1966) examined the hydrodemetallation

of vanadium and nickel in varous fractions of crude oils, and fit

-49-

A. Before HDS

-- s

Resin-like

Molecules

B. After HDS

S

a

Sulfur

Vanadium

0 Nickel

AN

Fig. 2-10

Aromatic Rings

Naphthenic Rings

Qualitative Changes in Asphaltenes and Surrounding

Resins During HDS Processing.

(Beuther and Schmid (1963)).

-50their data by first order kinetics.

removal rate of vanadium.

They also reported the higher

Some experiments to proved that vanadium

complexes have higher polarity and concentrate more on the edge of

asphaltene moleale were also conducted by them to support the earlier

theory proposed by Beuther and Schmid (1963)

vanadium removal rate.

Arey et al.

(1967)

that explained the higher

reported nickel is charac-

teristically more difficult to be removed than vanadium and the hydrodesulfurized product of Kuwait Atmospheric Residuals tends to be

relatively rich in nickel.

porphyrin in residual oil is

Kwan and Sato (1970) proposed that vanadylthen

directly adsorbed to the catalyst,

the porphyrin ring is broken down, the material is transformed into

non-vandyl compound, and finally deposited on the catalyst.

and Duhaut (1970)

Audibert

studied the commercial hydrodesulfurization of

residuals from several Middle-Eastern oils.

They found that demetall-

ation reaction for vanadium to be 15-20% faster than nickel, and

reaction ratio are roughly linear with hydrogen pressure.

Inoguchi

et al. (1971)-(a) maintained that the hydrodemetallation rate can be

described equally well in terms of either first

The activation is

than nickel,

10 kcal/g mole.

or second order kinetics.

Although vanadium removal is

faster

the selectivity for vanadium removal and nickel removal

varied with the reaction temperature; when reaction temperature is

creased,

in-

the selectivity for nickel removal also increase and reached a

maximun at 400 0 C then decreases as temperature is further increased.

-51An investigation made by Oxenreiter et al. (1972)

on the hydrodesulphuri-

zation of some redisuals shows that at their operating conditions,

is

there

66% vanadium and 56% nickel removal for Gach Saran residual, 63%

vanadium and 36% nickel removal for Khafji residual.

They also showed

that the demetallation rate for resin fraction of residuals is faster

than the asphaltene fraction.

tallation over manganese

tant of 5-12

Chang

and Silvestri (1974) found deme-

modules to be first

hr at 750OF (40000), which is

-

mentioned in section (2.2-1.a).

order,

much

with a rate cons-

higher than a thermal rate

They believed that the mechanism of

hydrodemetallation involves reduction and deposition, plus hydrogenation

of the hydrocarbon moiety.

Shah and Paraskos (1975) indicated the higher

vanadium removal rate for Kuwait crude oil.

In the publication of 1976,

Chang and Silvestri maintained their earlier statement in 1974, and also

used Co0-MoO3 /Al 20 3 for comparison.

Oleck and Sherry (1977) claimed

that up to about 83% metals removal, demetallation reaction are best

described by second order kinetics.

The activation energy for vanadium

removal is 38.2 kcal/g mole for CoO-MoO 3 /Al 2 03 catalyst and 26 kcal/g mole

for manganese nodules, the hydrogen pressure dependence is

one for both vanadium and nickel.

larger than

Riley (1978) supported the first

order kinetics as well as the higher removal rate for vanadium.

A

summary of these studies is shown in Table 2-6.

By comparison, the related hydrodesulphurization reaction is also

often described as either first order with respect to the sulphur compounds (Frost and Cottingham (1971),

Schuit and Gates (1973),

and

Schuman and Shalit (1970)) or second order (Watanabe et al. (1970),

T1able 2-6

Summary of Previous Studies on Kinetics of Catalytic Hydrodemetallation

Kinetic

Catalyst

Used

Authors

Crude

Order

E

V removal rate

(kcal/g mole)

Ni removal rate

Order of

Dependence

on H2

(1) Beuther &

Schmid

HDS

Catalyst

Kuwait

Reduced

2

----

----

I

----

----

----

----

----

1

Crude

(1963)

&

(2) Larson

Beuther

(1966)

Kuwait

Atmospheric

Residual

(3) Arey

et al.

(1967)

(4) Audibert

(5)

Middle

& Duhaut

Eastern

(1970)

Oils

Inoguchi

et al.

Khafji

Atmospheric

(1971)-(a)

Residual

(6) Oxenreiter

et al.

Khafji

& Gach

(1972)

Saran

1 or 2

----

----

----

----

10

-

1

Function of

Temperature

----

Residual

(to be continued)

MW

Catalyst

Crude

Used

Authors

Kinetic

Order of'

Order

Dependence

E

(kcal/g mole)

V removal rate

Ni removal rate

on H

2

&

(7) Chang

Silvestri

(1

Agha Jari

Topped

Manganese

Nodules

9 7 4)

HDS

Catalyst

Kuwait

Crude

Chang

Silvestri

Manganese

Nodules,

(1976)

Co-Mo/Al

Kuwait

Residual,

Agha Jari

&

(8) Shah

Paraskos

7 1

I

Crude

--

--

---

1

-

(11)

Manganese

Nodules,

(1977)

Co-Mo/Al20

Kuwait

Lagomedio

Atmospheric

Residual

Riley

Co-Mo/Al2

(1978)

1

03

2

Residual

Co-Mo/Al

<1 for 2 0 3

Manganese Nodule

Safania

Atmospheric

for

Co-Mo/Al 2 03

Smaller 2__for Others

1 for

&

Sherry

Oleck

>1

1

38.2

(Co-Mo/Al 2 03

)

,

Topped Crude

&

(10)

9

& PoroceI 3P

&

(9)

&

(1975)

26

(Nodule)

>1'

-54Massagutov et al. (1967), Beuther and Schmid (1963), and Oleck and

Sherry (1977)).

Riley (1978).

Fractional order (1.5 order) is also described by

The activation energy for hydrodesulphurization appears

to be in the range of 27 to 45 kcal/g mole (Oleck and Sherry (1977),

Schuman and Shalit (1970),

Cottingham (1971)).

Watanabe et al. (1970),

and Frost and

Although Audibert and Duhaut (1970)

claimed

that metal removal has higher activation energy than sulphur removal,

it

is not generally true.

The hydrogen dependence for sulphur removal

appear to be first order (Oleck and Sherry (1977),

Watanabe et al. (1970),

Schuit and Gates (1973)).

For hydrodenitrogenation which might occur along with hydrodemetallation and hydrodesulphurization, Flinn et al. (1963) reported that

the total nitrogen removal from quinoline in a paraffin oil over

NiO-W/Al203 catalyst was first order with respect to quinoline.

Aboul-

Gheit and Abdou (1973) also claimed first order kinetics with respect

to total nitrogen content.

Shih et al. (1977)

also fitted their data

with first order kinetics in their study of hydrodenitrogenation of

quinoline in white oil over NiO-MoO3 /Al 2 03 catalyst, their report also

show that hydrogen dependence is less than first order and the

apparent activation energy for total nitrogen removal is 25 kcal/g mole.

There appears to be a relationship between the metal removal rate

(especially vanadium) and the sulphur removal rate.

Massagutov et al.

(1967) studied the relationship between sulphur removal and vanadium

removal, sulphur removal and nickel removal respectively.

A very good

-55linear relationship was obtained between sulphur removal and vanadium

removal.

Their result is shown in Figure 2-11.

also reported by Richardson and Alley (1975),

(1971),

Similar result was

Frost and Cottingham

This clearly shows that metal

Inoguchi et al. (1971)-(b).

(especially vanadium) compounds and sulphur compounds are closely

related in residual oils, which is

Figure 2-10.

Yen (1977)

consistent to the model shown in

mentioned that one of the reason for the

association of asphaltene sheets is due to O=V ..... X (X=0,N,S) or

0=V ..... 7C

from resin and asphaltene sheets.

The processing of

residual oils requires hydrogenation.

As the association of X

V=0 (X especially S) and

as well as,-7lt-bond should be

IT.....

V=0,

...

overcome to let the sheets accessible for hydrogen attack, this will

result in the proportionality of vanadium removal to sulphur removal.

Although there has been a deviation regarding the kinetic order

of hydrodemetallation, almost all of the authors who claimed second

order kinetics agreed that the metal complexes can be divided into

two groups, each following a first order kinetics with different rate

constant and perhaps different initial concentration; the result of

conversion versus residence time would be difficult to distinguish

from the results of a second order reaction.

(1963),

(Beuther and Schmid

Inoguchi et al. (1971)-(a), Oleck and Sherry (1977), and Mosby

et al. (1973)).

Similar thing for hydrodesulphurization were metioned

by Schuman and Shalt (1970), Riley (1978), de Bruijn (1976), and Arey

et al. (1967).

We have shown that the two first order kinetics can

be used to approximate a second order

kinetics only at less than 92%

I00-

Q

& oo

PA.

0 60

0

U'8

12

-

60 ---

-

IX

~60 i

-

-2

0

0

z0

GO

00V,0

I~

20

IN

6u

so

20

IOU

S ULPHUR REMOVAL,/.

-Nickel removal versus vacuum gas oil

desuiphurization level.

60

s0

reioval i'crsus vacuun gas oil

desuipliurization level.

V: vacuum gas oil from Chckmagush crude oil; 0: vacuum gas

oil from Arlan crude oil: x vacuum gas oil from mixture of

Tuimaza and Arlan crude oils; 0: data reported by Connally';

0: data reported by Eberlinc'O; +: data rcported by Lewis";

A: data reported by Abbott 1 2 ;

Sulphur Removal Versus Nickel Removal (Left) and Vanadium Removal (Right)

(Massagutov et al. (1967)).

S

.

for Several Vacuum Gas Oil.

too

-Vanadiun

V: vacuum gas oil from Chcknmagush crude oil; 0: vacuum gas

oil from Arlan crude oil; x : vacum gas oil from mixture of

Tuimaza and Arlan crude oils; 0: data reported by Connally';

0: data reported by LbEhrlinc10; &: data reported by Abbott";

Fig. 2-11

90

SULPH UR RE MOVAL,O/.

-57conversion, and only when the ratios of the parameters of the two

first

within very narrow ranges, the result

order reaction fell

is shown in Chapter

5.11.

There has been some study on the effect of composition of catalyst

on hydrodemetallation, Chang and Silvestri (1974) compared two ocean

nodules catalysts which contain substantial amount

of Ni, Mo and Co

with fresh water nodule which has only trace amount of Ni, Mo and Co,

and found the ocean

nodules.

nodules are not more active than fresh water

In their publication of 1976, they compare- comercial available

Coo-Moo 3 /Al 2 03 with Lake Michigan Nodules and porocel on hydrodemetallation, and found that for hydrogen pressure higher than 800 psig,

2

0

is

more active than the other .two; while for pressure

lower than 800 psig, nodules is

Oleck and Sherry (1977)

more active than CoO-MoO 3/Al

2

03

'

Coo-Moo /Al

shows CoO-MoO /Al203 is always more active

than manganese nodules; while Riley (1978)

claimed that vanadium

removal activity is independent of the loading of Co and Mo on alumina.

As in the previous studies the demetallation reaction is either

diffusion limited or on the verge of diffusion limited, no conclusive

statements can be made if there exists deviation about the pore

structure of different catalysts.

Oleck and Sherry (1977) explained

the higher activity of CoO-MoO 3/A1 2 0 3 by larger pore size.

Chang and Silvestri (1974)

showed that the effectiveness factors

for demetallation with manganese catalyst is 0.55 when average catalyst

size is 1 mm, and 0.95 when it is 0.2 mm.

Shah and Paraskos (1975)

argued that the effectiveness factor for demetallation reaction can

-58not exceed 0.4.

Riley (1978) showed that vanadium removal activity

Similar

actually increases as the pore diameter of catalyst increases.

results were observed by Shah and Paraskos (1975), Spry and Sawyer

(1975),

Inoguchi et al. (1971)-(c), and Hardin et al. (1978).

As

Hardin et al. (1978) observed that more coke is formed on catalysts

while less metals per unit area are formed on catalyst that has larger

pores, it was proposed that there exists an optimum pore size for the

design of hydrodesulphurization catalyst.

As previously mentioned, substantial amount of metal compounds

exist in the asphaltene fraction of residual oils; in order for the

metals to be removed from asphaltene molecules, the large asphaltene

molecules have to diffuse into the catalyst.

asphaltene, only 10~7-10

obtained (Newson (1975)).

Due to the size of

cm /sec of effective diffusivity can be

This will explain the low effectiveness

factors for demetallation reactions.

As shown in Table 2-6, except the kinetic order, no sufficient

information were given to led to an understanding of demetallation;

a study based on model metal compounds dissolving in clean oils and

diffusion free conditions would provide useful kinetic data.

Deposition of Metals on Hydrodesulphurization Catalysts.

2.2-2

2.2-2.a

Concentration Distribution of Vanadium and Nickel on

Spent Catalysts:

Scanning electron x-ray microanalyzer was used for the study of

the deposition of metals on catalyst.

Arey et al. (.1967) mentioned

-59that nickel tends to be deposited throughout the desulphurization

catalyst particules whereas vanadium is concentrated in the outer

These metallic deposits many render the inner portions of the

layers.

catalyst particle inaccessible to the feed stock.

Audibert and

Duhaut (1970) showed that while vanadium has diffused into the

pellets up to 650 micron depth only, most of the nickel concentration

has been measured inside the pellets;

deeply than vanadium.

Kwan and Sato (1970)

Inoguchi et al. (1971)-(a)

tion.

that is,

nickel diffuses more

shared the same observa-

found that though nickel is

similar

in behavior to vanadium which tends to deposit more on the edge of the

catalyst than at the center, it spreads out more widely on the whole

catalyst than vanadium does.

Todo et al. (1971) observed that both

vanadium and nickel only deposited on the edge of the catalyst; that

is, the concentration profiles for both nickel and vanadium are of

U-shape.

Sato et al. (1971) claimed that while vanadium deposition

is of U shape, nickel tends to be uniformly distributed.

shows their result.

(1972)

Figure 2-12

Finally, an investigation made by Oxenrieter et al.

shared the same view as Sato et al. (1971).

The general observation from aformentioned references is

that

vanadium always distributed more on the edge of the catalyst while

nickel tends to be more uniformly distributed.

The deviation may

be due to different particle size and pore structure of the catalysts

used in different studies.

Although in section 2.2-1 we have mentioned

that vanadium removal rate is always higher than nickel removal rate'

-60-

8

WV

6CQ 5W0

300

400

2W

100

0

NO 220 300 400 5W0- C.W

0

.o6 0 403 300 200 100

0 100 200 300 400 5O0

DISTANCE FROM CENTER OF CATALYST (/')

AFTER

Fig 2-12

50

HRS ON STREAM

Concentration Profile of Vanadium (up) and Nickel (Down)

on the Desulphurization Catalyst after 50hrs Reaction.

(Sato et al. (1971))

-61-

and also learned that both reaction might be diffusion limited.

However, the higher vanadium removal rate is not sufficient to explain

the big difference between the concentration profile of vanadium and

nickel shown in Figure 2-12.

Sato et al. (1971) did theoretical

calculation and showed that in order to achieve the big difference

of concentration profiles shown in Figure 2-12,

the effective

for vanadium has to be less than 10% of nickel, which is

impossible.

diffusivity

highly

There exists some unrevealed phenomena other than metal

removal activity and effective diffusivity that causes the big difference

in Figure 2-12.

2.2-2.b

Amount of Deposition:

From the information concerning the distribution of deposition of

metals on the catalyst layer, Kwan and Sato (1970) also found that the

deposition of carbonaceous substance takes place consecutively whereas

that of vanadium or nickel simultaneously.

The amount of vanadium and nickel deposited on the catalyst

depends on the duration of catalyst on stream and the amount of

metals in feed stocks.

As high as 56 wt% for vanadium,

17 wt% for

nickel were observed by Oxenreiter et al. (1972), while as low as

0.1 wt% for vanadium and 0.05 wt% for nickel were observed by Kwan

and Sato (1970).

While the amount of deposition for vanadium and nickel on the

catalyst will increase with time of operation, coke deposition appears

to reach a saturation concentration and never increases again.