THINGS MADE STRANGE Destabilizing Habitual Perception Floor van de Velde

THINGS MADE STRANGE

Destabilizing Habitual Perception

BY

Floor van de Velde

B.F.A. Sculpture

MASSACHUSETTS COLLEGE OF ART & DESIGN, 2011

SUBMITTED TO the Department of Architecture in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

MASTER OF SCIENCE IN

ART, CULTURE, AND TECHNOLOGY

AT THE

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

JUNE 2014

© Floor van de Velde. All rights reserved.

The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created.

SIGNATURE OF AUTHOR

CERTIFIED BY

ACCEPTED BY

Department of Architecture, May 9, 2014

Azra Akšamija

Assistant Professor of Art, Culture, and Technology

Thesis Advisor

Takehiko Nagakura

Associate Professor of Design and Computation

Chair of the Committee on Graduate Students

T H ES I S CO M M I T T EE

THESIS Advisor

Azra Akšamija

Assistant Professor of Art, Culture, and Technology

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

THESIS READER

Mark Goulthorpe

Associate Professor SMArchS

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

THESIS READER

Catherine B. Lord

Professor Emerita

Department of Art, University of California, Irvine

THINGS MADE STRANGE

Destabilizing Habitual Perception

Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 9, 2014 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master of Science in Art, Culture, and Technology

THESIS Advisor

Azra Akšamija

Assistant Professor of Art, Culture, and Technology

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

A B S T R AC T

Technology mediates our perception of the world. The tools of contemporary society’s digital habit aim for transparency, creating an inextricable link between the human body, perception and life-world.

The resulting entanglement between humans and technology challenges the sensorium: illusion and reality seem to co-exist, space and time become compressed, and human relationships transmute into constant digital connections.

This intimate yet tenuous bond with technology can automize perceptual processes, leading to habitual perception: we recognize the world around us, but we cease to really see what is there. We are increasingly in danger of losing sight of how we exist within a technologically saturated environment, how we cultivate our curiosity, how we create, how we perceive, and ultimately: how we ought to move forward without losing the sense of how we relate to each other and who we are as humans.

Art has the ability to subvert, highlight, and elucidate our tenuous relationship with technology, and to defamiliarize, “make strange,” and shake up automized and habitual processes of perception as to re-establish a critical awareness of perception and perceptual processes.

In this thesis, I explore the creative strategy of defamiliarization in my own practice and regard the works that I have produced at MIT as experimental and experiential frameworks that have the capacity generate the awakening of critical awareness of perception. Besides providing documentation of projects, these texts may be also be read as a non-linear record of the research, questions, and experiments related to the philosophy of technology, the relationship between art and technology, and the perceptual processes linked to experiential art.

THINGS MADE STRANGE

Destabilizing Habitual Perception

FOR ELAINE

CO N T EN T S

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . . . . 13

PREFACE . . . . 14

INTRODUCTION . . . 17

METHODOLOGY . . . 25

VIBRANT DIVIDE

29

FOR MARCEL

59

79

SCORE FOR

RHOMBI WALL

47

67

MIRROR FOR

LATENCY

87

FLOOD

APPENDIX . . . . 98

IMAGE ATTRIBUTIONS . . . . 110

BIBLIOGRAPHY . . . . 112

AC KN OW LED G M EN T S

I would like to thank many people who have helped me through the completion of this thesis. The first is my advisor, Azra Akšamija, thank you for your support, advice, time, and great sense of humor. You are the true embodiment of a mentor. I was also blessed to work with my very dynamic and thought-provoking committee members Professor Mark Goulthorpe and the amazing Catherine Lord. Thank you to both. Thank you also to

Zenovia Toloudi and Josephine Dorado for listening to some of my earliest ideas. To the lecturers and professors of ACT and Harvard, past and present: Giuliana Bruno, Martha Buskirk, Howie Chen, Andrea Frank,

Renée Green, Florian Hecker, Joan Jonas, Jesal Kapadia, Antoni Muntadas, Gediminas Urbonas, and Krzysztof Wodiczko. To Laura Anca Chichisan, Val Grimm, and Marion Cunningham, thank you for the fast and efficient help. There are quite a few more people to thank at MIT: a special thank you the stellar Seth (Sethie!)

Avecilla, fabrication expert, shop manager extraordinaire and willing collaborator in all my ambitious and sometimes foolish projects. You have been an absolute pleasure to work with. Thank you Madeleine Gallagher for always having the cables, gadgets and gizmos at the ready and for having a wicked sense of humor. To Patsy

Baudouin for her expert librarianship, stimulating conversations, and for ordering so many amazing books.

Thank you to the amazing group of individuals at the MIT Office for the Arts who work tirelessly to support the arts at MIT: Meg Rotzel, Leila W. Kinney, Susan Cohen, Sam Magee, Elizabeth Murphy, thank you for all the support, grants, and opportunities you’ve given me during my time at MIT. A very special thanks to Lucas

Spivey and Elizabeth Woodward from Cox Gallery: thank you for believing in me and giving me my first solo show. To all the amazing professors at Massachusetts College of Art and Design who have been incredibly supportive over the past few years: Rick and Laura Brown for the endless requests for recommendation letters,

Taylor Davis, Judith Haberl, Judith Leeman, Joanne Lukitsh, Dana Moser, David Nolta, and Nita Sturiale.To my friends at the Media Lab: the fabulous Pip (Patsy!) Mothersill, thanks for the laughs and for being you.

David Cranor, Arthur Petron, Edwina Portocarrero, Dan Novy, and Sophia Brueckner, thanks for always welcoming me into Media Lab fun times. To wonderful and warm friends James Lord, Roderick Wyllie, Alison

Sant, Rick Johnson, Lloyd Speed, Bill Ciccariello, Brent Refsland, Rosa Chohen Refsland, Kadet Kühne, Lydia

Matthews, Paul Benney, Noritaka Minami, Jessica Gath, and Christo Wood. To all the Buckholtzes! Jack, Kay,

Jeanne, Mary, and Sharon.

To my family so very, very far away in Belgium: Wivine, Noël, and Stien for always being supportive of my endeavors, adventures, and travels. Special thanks to my father for taking the time to read my thesis drafts three times and for making so many great suggestions.

And last but certainly not least, the biggest thank you of all thank you’s to Elaine, who waited and watched in patience, supported me through every step of my education here at MIT and MassArt, and listened to all my outlandish ideas for projects and experiments. Thank you for spoiling me rotten all the time. These words would never have seen the light of day had it not been for my partner in life, adventure, learning, laughing, and everyday thriving.

This one is for you ...

13

P REFAC E

B efore coming to MIT, I labored for eight or more hours a day in front of a computer screen, pushing pixels for a somewhat descent living (in New York standards, that is). After several years of profound engagement with bits, bytes and endless hours of catching rays in front of a glowing rectangle, I felt exhausted, frustrated, and overwhelmed. As a frequent flyer on the Cyber Highway,

I was submerged by the constant over-stimulation, endless creative possibilities, and unlimited access to information.

Technology magazines, art journals, websites, and newspapers announced that the democratization of creativity was upon us. Rejoice!

Anyone could now be a DJ, a painter, a writer, a publisher, a curator. I felt excited to be a part of this incredible moment: the Digital Revolution that brought with it the new era of hyper-space, hyper-time, hyper-everything where you may upload, download, stream anything at anytime.

Needless to say, things didn’t quite work that way. The fairy tale told above of the promised creative brilliance that would manifest with the time and money invested in the gadgets, gizmos, and tools sold by software and hardware giants often ended badly.

14

I suspect I’m not the only member of this cut-and-paste, post-post modern society that feels buried under too much of … everything. We are increasingly in danger of losing sight of how we exist within a technologically saturated environment, how we cultivate our curiosity, how we create, how we perceive, and ultimately: how we ought to move forward without losing the sense of how we relate to each other and who we are as humans.

By no means should this thesis be read as an “anti-technology” manifesto.

Rather, I hope to use the work I have produced over the past two years during my time at MIT as experimental and experiential frameworks, in the hope of discovering some insights, some answers, and some future goals in my practice. The aim of this thesis is to investigate some of the above questions, to probe these in relation to my own practice, and to articulate the thinking, making, and production of projects completed during my two years at MIT.

Art has the ability to subvert, highlight, challenge, and elucidate our tenuous relationship with technology. What I am ultimately trying to understand and foster in my own practice is the potential to use art as a vehicle to create meaningful relationships between humans and technology.

Lastly, it should be noted that I am writing this document with a Western societal perspective and am fully aware that only a very small percentage of the worlds’ population have access to the range and diversity of technologies, creative freedom, and free speech that I have access to in this thesis and in my life.

15

I N T RO D U C T I O N

What we need is respite from an entire system of seeing and space that is bound up with mastery and identity.

To see differently, albeit for a moment, allows us to see anew.

PA RV EEN A DA M S

B r u c e Na u m a n & t h e O b j e c t o f A n x i e t y, 1 9 9 8

T he root of technology, techne — the ancient Greek Goddess of practical knowledge — meaning “art” or “craft” in Greek, originates from the even earlier Indo-European root teks, meaning

“to weave” or “to fabricate.”1 Tracing the etymology of technology is a complex endeavor: like many other concepts and terms, meaning is derived from a word’s value, translation, and context within society.

Archaeological evidence shows that the weaving of cloth dates back to 35,000 BCE, predating the birth of agriculture.2 The bones, artifacts, and tools of our ancestors point to a close connection between humans, the tools they used, and the artifacts they made. In fact, archaeologists have been known to date the skulls and bones by the tools found near them.

Will we too, in the future, be dated by the tools found near and perhaps even in our graves? What will future generations make of the masses of obsolete digital devices, circuit boards, gadgets, and gizmos they might unearth, and what narratives would our descendants be able to construct from their observations?

1 Morton Winston and Ralph Edelbach, Society, Ethics, and Technology

(Boston: Cengage Learning, 2013), 2.

2 Ibid,. 2.

17

Making any kind of meaning from technology by referencing the techniques and tools, whilst ignoring the resulting artifacts, is restrictive in the context of human-technology relationships today. Contemporary society has a tendency to narrow the meaning of technology to the gadgets and tools of the Information Age.3 For Heidegger the fundamental nature of technology cannot be found within itself but should rather be thought of as something that belongs to human activity.4 It is not the gizmo or gadget, but our mental adaptation to the tools and techniques that we invent that changes human cognition and mental capacity and is fundamentally connected with the question of being:

Thus we shall never experience our relationship to the essence of technology so long as we merely conceive and push forward the technological, put up with it, or evade it. Everywhere we remain unfree and chained to technology, whether we passionately affirm or deny it.5

What does it mean to practice art in the Information Age? The shift in the past century from a manufacturing-based economy to an information-based economy provides artists the opportunity to position themselves as information providers, visionaries and interpreters.

3 Ibid., 287.

4 Martin Heidegger, The Question Concerning Technology, and Other Essays

(London: Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2013), 286.

5 Ibid., 287.

18

For many contemporary artists, the modes and methods of information technology permeate almost every aspect of the creative process — from creation to production, distribution and marketing, to the preservation and support of art works — that are driven by binary code.

Software, hardware, and digital tools in the studio enable artists to explore and create in ways that were not previously possible. Artists are often early adopters of new technology and break, hack, and abuse tools in conceptual and experimental work. As Paul D. Miller states, the incorporation, deconstruction, and aesthetic examinations of technologies can produce entirely new creative investigations:

Today’s notion of creativity and originality are configured by velocity: it is a blur, a constellation of styles, a knowledge and pleasure in the play of surfaces, a rejection of history as objective force in favor of subjective interpretations of its residue, a relish for copies and repetition, and so on.6

Artists working with the tools of the information-communication age often perform a dance between translations. Image translates to code, and code translates back to image. Gestural and whole-body interactions are converted by motion-sensors, and the code produced by the sensors produce conditions for the body to react in response.

6 Paul D. Miller, Rhythm Science (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2004), 76.

19

This reversibility between content and data has become a fluid and effortless process for programmers and artists alike as they adopt new technologies and tools into their practice with ease.

On the other hand, technologies change so rapidly, that standard operating manuals do not apply. As Stuart Brand points out, in order to survive, artists need to keep up with the latest developments or suffer the consequences:

Once a new technology rolls over you, if you’re not part of the steamroller, you’re part of the road.7

Technology does not transcend society, but constantly reconfigures human vision, cognition, and perception. In an environment saturated with images and embedded with pervasive, ubiquitous technology, our vision is shaped by how technologies of vision teach us to look and see. This new “techno-logic” alters our perceptual orientation in the world and seeing images “mediated and made visible” by technologies of vision allow us not only to see “technological images,” but also to “see technologically.” 8

We are virtual flâneurs, oscillating between attentiveness and distraction as we traverse on-line, networked spaces. Fragments of information, images, and continuous updates vie for our attention. The human sensorium is challenged: our bodies cannot escape technological mediation, our perception of space and time are reconfigured and we find ourselves in an environment where illusion and reality seem to co-exist.

7 Steward Brand, The Media Lab: Inventing the Future at MIT (London: Penguin

Books, 1988), 9.

8 Vivian Sobchack, The Scene of the Screen: Envisioning Cinematic and Electronic “Presence” in Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht and K. Ludwig Pfeiffer (ed), Materialities of Communication

(Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1994), 88.

20

Network-based models of communication convince us that we have become closer, yet we feel further from each other. Unlimited access to information makes us seem more educated, yet we feel deceived and deluded by often conflicting, trivialized or sensationalized news. Pervasive mobile technology makes us available 24/7, yet we feel more alone than ever. Sherry

Turkle who writes extensively about the nature of human relationships on the Internet, points out that when given the chance to create an on-line version of ourselves — our avatars — we tend to create a superior copy of our real person. Technology has the power to seduce human vulnerabilities while “promot[ing] itself as the architect of our intimacies.”9

Over the course of recorded human history, as new modes of perception and technologies of vision have been introduced, some of these inventions would have a lasting impact on how humans perceive, experience, and represent the world: telescopes brought the sky to our eyes, bringing blurry celestial bodies into focus, the invention of the microscope would make the invisible visible for the first time, and the impact of Renaissance linear perspective is still palpable in Western visuality and representation today.

Tools such as the microscope and the telescope are becoming increasingly powerful, expanding our visual limits to experience visuals from nano-level all the way to interstellar space. With each new technology or device, human perceptual processes changes, however, our individual observations of the world still depend on the cultural and conceptual framework we are familiar with.

9 Sherry Turkle, Alone Together Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each

Other (New York: Basic Books, 2011), 29.

21

Today, ubiquitous and pervasive computing, wearable devices, and embodied technologies extend human and biological perceptual capabilities. The tools of contemporary society’s digital habit aim for transparency, creating a seamless, inextricable bond between the human body, our perceptual processes and the life-world.10 This close entanglement between humans and technology challenges the sensorium: illusion and reality seem to co-exist, space and time become compressed, and human relationships transmute into constant digital connections.

We are increasingly becoming unaware of how our perception is being mediated on a daily basis. Our intimate yet tenuous bond with technology leads to automized and habitual perception: we recognize the world around us, but we cease to really see what is there.

Victor Shklovsky differentiates between “recognition,” or “automized perception,” and “seeing.” 11 When we look at something without seeing it, we are in a mode of recognition. Seeing goes beyond mere recognition. It is the surprise, the double-take, the awakening. It is the moment when we experience something for the first time:

A phenomenon, perceived many times, and no longer perceivable, or rather, the method of such dimmed perception is what I call ‘recognition’ as opposed to seeing.12

10 In phenomenology, life-world – translated from the German Lebenswelt – describes

the world immediately experienced in the subjectivity of everyday life, as distinguished

from the objectivity of the sciences. These experiences include our social, perceptual, and

practical everyday experiences.

11 Victor Shklovsky, Theory of Prose (Elmwood Park: Dalkey Archive Press, 1991), 6.

12 Ibid., 9.

22

In his essay Art and Technique, Shklovsky coins the term defamiliarization, a creative strategy and technique used in literature and theater in which common things are made unfamiliar. The purpose of defamiliarization is to create surprise in the mind, forcing the reader to see and hear things as if for the first time. Presenting familiar things in an unusual way — to “make strange” — can increase perceptual awareness by “slowing down” the process of perception. In literature, the use of poetic imagery “makes strange the habitual by presenting it in a novel light.” 13

The act of “creative deformation” counters the routine of perception, and can displace the “automatism of ordinary perception.”14 For Shklovsky, art is the ideal vehicle for defamiliarization, to “make strange,” complicate form, and expand the perceptual process, so that we “may recover the sensation of life:”15

And art […] exists in order to make one feel things, to make the stone stony. The purpose of art is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known.

The technique of art is to make objects ‘unfamiliar,’ to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged.16

13 Victor Shklovsky, Art as Technique in Russian Formalist Criticism. Four Essays (Lincoln

& London: University of Nebraska Press, 1965), 3.

14 Ibid., 7.

15 Ibid., 9.

16 Ibid., 9.

23

Shklovsky also points out that for art to function as a device for defamiliarization, the driving force is the experience or the outcome of the art work, not the object:

Art is a way of experiencing the artfulness of an object: the object is not important […]17

Starting from the assumption that art can act as a vehicle for destabilizing perception, the motivation of this thesis is to probe my own approaches towards defamiliarization in the projects I have worked on during my time at MIT. Inspired by the precursors of the specific movements that I’m interested in — practitioners that have broadened the realm of art to include works with no clear object except the viewers experience — my practice involves producing works that are predominantly experiential in nature.

For the purpose of this thesis, I focus on six projects that demonstrate different approaches towards defamiliarization as a creative strategy.

These projects could be observed as independent, one-off pieces, but also function as testing grounds for the research, inquiries, and questions about the nature of defamiliarization in non-objective experiential works of art.

What all these projects do have in common is an investigation into the boundaries of perception, space, and form. By taking advantage of recent technological advances in hardware and software, the works presented here combine light, non-pictorial visuals, form, sound, and color to create three-dimensional, experiential environments. The approaches towards defamiliarization range from experiencing space in new ways, to framing fictionalized memories, to creating absurd situations, to producing conditions for disembodied sensation, and finally towards experiential works that investigate total sensory deprivation.

7 Ibid., 9

24

M E T H O D O LO G Y

I n this thesis, I explore defamiliarization in my own practice and regard the works that I have produced at MIT as experimental frameworks that attempt to generate the awakening of critical awareness of perception. During the past two years, I have gradually transitioned from a traditional sculptural practice — an object-based practice that keeps the viewer’s body at a distance, making the object the point of contemplation

— to working with installation and experiential environments, where no clear object except the viewers’ experience becomes focal point of the work.

Besides providing documentation of the projects that I have worked on during my time at MIT, these texts may be also be read as a non-linear record of the research, questions, and experiments related to the philosophy of technology, the relationship between art and technology, and the perceptual processes in experiential art. The works included are sculptures, installations, and environments that are predominantly experiential in nature and that explore the peripheries of space, time, and form.

25

The choice for presenting these works in a non-chronological, non-linear fashion is deliberate. However, the reader will find a common thread running through these projects Starting with a brief description of the work, each chapter in this thesis continues from the introduction of the project into a deeper investigation and narrative that explores approaches of defamiliarization. Most of these questions revolve around perception, experience, form, space, time, space-time, and the nature and use of light in a visual practice.

Vibrant Divide, a large site-specific artwork constructed from fluorescent acrylic draws the viewer’s attention to a realm of space that is often neglected, viewed in Western tradition as negative space. Inspired by the Eastern concept of ma, an embodiment of space that incorporates time as an experiential factor, and gesturing towards the space that exists in-between, around, and behind, Vibrant Divide has a destabilizing effect on the conventional understanding of space.

Chapter II introduces Sounds of the Earth, a sound sculpture inspired by a joint venture between Carl Sagan and NASA. As with Vibrant Di-

vide, Sounds of the Earth is an investigation of space: outer space. Based on NASA’s mission — the dispatch of two space craft containing human representations in the form of text, imagery, and sound into space for possible extraterrestrial communication — Sounds of the Earth imagines, and re-imagines a reality beyond our own.

26

For Marcel, the focus of Chapter III, is based on a responsive sound sculpture. The fictional framing of an imaginary dialogue between Marcel Du-

champ, an art critic, and composer John Cage, invites the viewer to enter into a pop-up theater. The unusual combination of objects paired with a tongue-in-cheek dialogue between the artists, creates an absurd and unfamiliar sonic event.

The disembodiment of voice is the focus for the project featured in Chapter IV. In Mirror for Latency, the viewers’ physical expectations are thrown into question in an installation that examines our perceptual processes in relation to time, duration, and feedback. Latency, or the delay between a signal’s creation and reception, is a common occurrence in conversations we have with each other over a network. The re-creation of this latency in real life produces a sense of detachment, defamiliarizing the viewers through a delay in the projection of their own voice.

In Chapter V, Score for Rhombi Wall invokes a way of thinking and finding one’s way through the haptic sensation of surfaces. Depth and texture are produced using the beam from a video projector and using projection mapping techniques, creating a tromp l’oeil effect, casting the viewers’ stability of perception into question.

The final chapter of this thesis focuses on a project that explores sensory deprivation. Flood is an ephemeral installation informed and inspired by the sensory experiments of Robert Irwin and James Turrell during their collaboration at LACMA in the late 1960s. Denying viewers access to some of their senses for a prolonged period of time, creates conditions for a deeper appreciation of the perceptual processes involved.

27

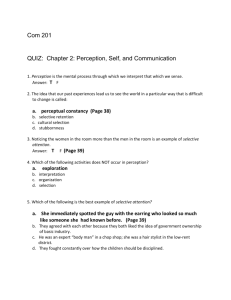

Figure 1: Vibrant Divide (2014) - installation view

29

V I BR ANT DIV IDE

All material is spent light. It is light that has become exhausted.

LO U I S KA H N

L e c t u re a t Pr a t t I n s t i t u t e , 1 9 7 3

間

( m a )

The garden is a medium for meditation

Perceive the blankness

Listen to the voice of the

silence

Imagine the void filled

A RATA I S O Z A KI

MA, Space / Time in the Garden of Ryoan-Ji

30

Figure 2: Vibrant Divide (2014) - DETAIL

31

Figure 3: Vibrant Divide (2014) - DETAIL

32

V I B RA N T D I V I D E

(2014)

P RO J E C T D ES C RI P T I O N

Digital Acrylic Fabrication

Materials: Fluorescent acrylic and black light 1

Dimensions: 92 x 40 x 48 inches

Vibrant Divide is composed of seven large hanging sheets of fluorescent pink and orange acrylic. Suspended from the ceiling, the sculpture appears as a floating, neon-orange box, divided by exterior vertical lines and interior diagonal lines, etched into the material itself.

Viewed under a matrix of black light, the sculpture is an exploration in the relationship between material, light, and fluorescence.

Each surface is etched with diagonal bars, alternating in direction on every other plate. The bars are layered as the viewer combines and flattens the seven separated screens in their field of vision. A repeated “X” pattern emerges, as if to deny the viewer to see what lies beyond.

1 Light that emits ultraviolet or infrared radiation, invisible to the naked eye.

33

M y relationship to the experience of space is informed by a lifetime of constant displacement: arriving as the immigrant, leaving as the migrant. The desire for space to exist becomes instinctive: nomadic existence and the making of space-within-space is a yearning to produce a feeling of belonging somewhere. This decentralized, immigrant-migrant view of my surroundings serves as a key motivation to create installations and sculptures that produce a sense of space that is both expansive and intimate. Fill(ing) space is making form.

Void space is … a quandary.

I was brought up with “Western” notions and concepts of space which revolves around dichotomies such as object/non-object, void/filled, and positive/negative. The Oxford English Dictionary defines “negative space” as “an area of a painting, sculpture, etc., containing no contrasting shapes, figures, or colors itself, but framed by a solid or positive form, esp. one that constitutes a particularly powerful or significant part of the whole composition.”1 This seemingly uncluttered and unambiguous definition of negative space suggests that space can simply be divided into positive space, that which is there, and negative space, or that which is not there.

Notions and concepts of space and spatial practice that pervade Ocean-

1 “Negative space,” Oxford Dictionary, Online edition, accessed on 3 March, 2014.

34

ic cultures includes the relationship of space to time. Space becomes a gap, an opening, suggesting the time (in)between, or the space between: space becomes an embodied experience. In Japan, negative space does not mean non-existence, but is rather a consciousness of space and time, known as ma. The words of Arata Isozaki describing the Ryōan-ji garden in Kyoto — one of the last surviving Japanese dry gardens — illustrates the fluid relationship between the garden as the “medium” and the

“blankness,” or the “voice of the silence,” a silence that is not void, but instead is the element that allows for a condition for meditative practice. 2

The rocks are arranged in space in such a way that eventually the viewer ceases to be aware of the object — the rocks — or the space around the rocks — the raked white sand — and instead becomes enveloped in the experience of time-space continuity.

Inspired by his visit to the Ryōan-ji garden in 1962, John Cage drew

2 Arata Isozaki. Ma Space - Time in the Garden of Ryoan-Ji. Short, directed by Takehisa

Kosugi (1989; Kyoto: Program for Art on Film, Metropolitan Museum of Art and the

J. Paul Getty Trust), Color film.

35

Figure 4: John Cage: SKETCH FROM Ryōanji (1963)

36

170 sketches of his impressions and composed Ryōanji (1983), a sparse, minimal piece of music that echoed the contemplative spirit of the dry garden: the space in-between, pause and random starts of woodblocks paired with bells are punctuated by the occasional glissando and growl of a bass trombone.

Cage developed chance techniques for his musical compositions that also served as aesthetic prompts in his drawings: the choice and positioning of the stones are expressed in free-form operations executed with graphite on paper. Here, ma becomes the composer’s stream of conscious.

A series of Zen-inspired non-decisions. The drawings illustrate Cage’s idiosyncratic sensibility as the spaces around and in-between the rocks portray random, circular doodles, a humorous and polar take on the neatly raked white sand that surrounds the rocks in reality.

The concept of ma as a perception of time that embodies space-time is found in traditional Japanese Noh theater: the intervals or timing between structured parts in the performance, the “stillness and emptiness” that occurs before and after an onstage event, whilst the positive space is created by “stage properties and by the dramatic activities of performers.” 3 A room is described as ma when one refers to the space between the walls, and in music ma denotes the pauses and rests between the notes or sounds. Even in the daily Japanese conversation, the silence between conversations, or the time taken by speakers between arguments is known as ma.4

3 Charles Wei-Hsun Fu, and Steven Heine, Japan in Traditional and Postmodern

Perspectives (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995), 12.

4 Ibid,. 55.

37

Figure 5: John Cage meditating at the Ryōan-ji garden, 1963

38

Watching the projector beam move across a matrix of rhombi in Score for

Rhombi Wall 5 — one of my first forays into producing video sculptures that use light as a form-making factor — I observed how the interplay between light and shadow animated the surface. In Vibrant Divide, I sought to expand this notion by attempting to animate space by using texture and surface to capture the ephemerality of light. Working with translucency, reflection, and color mixing, Vibrant Divide creates a dance between luminosity and materiality.

Humans have a natural impulse to harness space. We need architecture to protect our bodies from the elements, from the implications of natural cycles. The built space around us creates tension, while apertures become our escape from the gravitational pull of the walls built around us and guide the flow of waves — whether sound, air, or light — in and out of space.

While Cage’s graphite drawings of the Ryōan-ji gardens renders ma in the flow of positive space through uncensored gestures of the composer’s hand, the site-specific architectural interruptions of Gordon Matta-Clark — apertures cut into built space — makes ma visible in the negative extraction of light from the exterior of the abandoned buildings.

5 A project description for Score for Rhombi Wall can be found in a later chapter in this thesis.

39

In what at first might seem to some like a violent act of vandalism, the gouging, splitting, and severing of the walls and partitions of the buildings was for Matta-Clark a gesture of compassion towards the building

— bringing relief to the built space in an exercise of extraction:

I see the purpose for that hole — it is an experiment in bringing light and air into spaces that never had enough of either.6

The aperture of the human eye conquers the visual world: perceiving at great distances, it picks up the “punctum,” the “accident which pricks,” and which “bruises [us]”7 as we scan and capture our future memory-images. Like the notes of a music composition, apertures in architecture can be fixed or variable: providing built space with rhythm, tempo, timbre, symmetry, and diversion.

Considering what aperture in architecture does as opposed to what it is, allows for the removal of formal connections and predeterminations of its meaning: aperture becomes a tool for its user or maker who may then

“script the way that an opening informs a space by thinking of it as an aperture rather than referencing an image of a particular object.” 8 Window, door, skylight … a passageway, a hallway, or an entry … perhaps an escape, or a chance operation at escaping darkness?

6 Gordon Matta-Clark, and Gloria Moure, Gordon Matta-Clark: Works and Collected

Writings (Barcelona: Polıgrafa, 2006), 59.

7 Roland Barthes Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (New York: Hill and Wang,

1982), 27.

8 James F. Eckler, Language of Space and Form: Generative Terms for Architecture (Hoboken,

N.J: Wiley, 2012), 145.

40

Figure 6: GORDON MATTA-CLARK - WORKS IN PROGRESS

41

But light is everywhere, even in the darkness of the corners of constructions. Light, the “giver of all presences” 9 was a central element in Louis

Kahn’s philosophy and architecture. For Kahn, all matter is light:

All material in nature, the mountains and the streams and the air and we, are made of Light which has been spent, and this crumpled mass called material casts a shadow, and the shadow belongs to Light.10

How might we capture light in matter? In Vibrant Divide, I read the volume of the gallery and responded to it by breaking the negative space with sheets of fluorescent acrylic. Suspended under a matrix of black lights, the luminous orange and pink plates captured, transmit and reflect light that flows into the negative space between the rectangular shapes.

The fluorescence — a form of luminescence and emission of light by matter that has absorbed light 11 — of these hanging sheets embodies light in a way that most material cannot. Of course, one might say of the digital screen that it holds and transmits light as well. The difference lies in the point of observation: a computer screen only becomes useful when we are situated in front of it.

9 Louis Kahn and Robert Twombly, Louis Kahn: Essential Texts (New York: W. W. Norton

& Company, 2003), 236.

10 Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (New York: Hill and Wang,

1982), 27.

11 “Fluorescence,” Oxford English Dictionary, Online edition, accessed on 3 March, 2014.

42

Figure 7: Vibrant Divide (2014) - DETAIL

43

With Vibrant Divide, the notion of screen is expanded. Movement and orientation becomes part of the viewer experience and the use of body displacement redefines the spatial navigation and relation between body and screen. The piece exists in three dimensions, and is viewed in three dimensions. With no fixed point of observation of light that is captured, transmitted, and reflected, Vibrant Divide becomes post-cinematic.

Negative space becomes illuminated by the reflections of the acrylic plates. The viewer is drawn into the space in-between, creating new conditions for spatial and temporal sensations. Similarly to the rhythm and intervals experienced in Japanese Noh theater, ma is experienced in the dynamic changes in rhythm and intervals of the glowing, guillotine-shaped plates that cut through volume in the galley space, creating a sense of defamiliarization for viewers, as they re-evaluate any preconceived, dualistic awareness of space, time, and form.

44

Figure 8: Vibrant Divide (2014) - installation view

45

S O U N D S O F T H E E A RT H

I had monuments made of bronze, lapis lazuli, alabaster … and white limestone … and inscriptions of baked clay …

I deposited them in the foundations and left them for future times.

ES A RH A D D O N , KI N G O F A S S Y RI A

S e v e n t h C e n t u r y B. C .

We can’t help it.

Life looks for life.

CA RL S AG A N

Pa l e B l u e D o t , 1 9 9 4

47

Figure 9: Sounds of the Earth (2011) - DETAIL

48

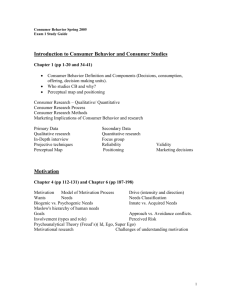

SOUNDS OF THE

EARTH

Light & Sound Installation

Materials: Antique darkroom light, acetate back-lit film, speaker drivers

Dimensions: 12”h x 10” w x 5.5”d

P RO J E C T D ES C RI P T I O N

Sounds of the Earth

is a sound installation based on a joint venture between NASA and Carl Sagan. In the hope that extraterrestrial life might find these craft in the future, NASA launched the twin

Voyager

1&2

in 1977 with two golden records attached, containing diagrams, text, imagery, and sound representative of life on earth.

An image of the golden record is cased in a Kodak Safety darkroom light, echoing the absurdity of sending a phonograph — an outdated method of playback — into interstellar space. Mounted on the wall, viewers listen to a soundtrack composed from samples of from the original

Voyager

recordings.

49

I f you had the chance to tell an extraterrestrial what the world was made of, what music we listen to, what we read, how we feel, eat, sleep, and communicate with each other, what would you say? What would you choose to include? How would you translate our linear, human time to post-human time? What maps would you draw? How would you give directions to a planet that might be light-years away?

On September 5th, 1977, forty-eight hours before I was born, NASA launched the Voyager 1&2, a dual spacecraft mission that would travel through our solar system and beyond — into interstellar space — to gather scientific information through the Deep Space Network.

Both spacecraft carry a 12-inch gold-plated phonograph record, containing sounds and images that evoke life and culture on earth. These golden records, the so-called The Sounds of the Earth1, was project initiated by Carl

Sagan, in an effort to introduce possible extraterrestrial life to human life.

NASA agreed to the project and gave Sagan six weeks to complete both records. If one were to consider the Lascaux and Chauvet cave paintings as the first frontier of human representation, the sounds, images, diagrams, and text that would ultimately travel into interstellar space could quite possibly become the “final frontier” of representations of human life and experience.

1 Ray Spangenburg and Diane Moser, Carl Sagan: A Biography (New York: Greenwood

Publishing Group, 2004), 90.

50

If you had to convey in a few brief seconds a message to another sentient being in the Universe, what would you say? To date there are more than

1,000 languages spoken in the world today. 2 The Voyager records included recordings of 55 languages, starting with Akkadian, spoken in Sumer about six thousand years ago, and ending with Wu, a modern Chinese dialect. The speakers were given no formal instructions as to what they should say in the recording, other than that the message was intended for the “ears” of extraterrestrial beings in the far future.

A very personal message in Swedish was recorded as: “Greetings from a computer programmer in the little university town of Ithaca, on the planet

Earth,” while a message in Mandarin Chinese sounded more like a casual postcard: “Hope everyone’s well. We are thinking about you all.

Please come here to visit us when you have time.” Some seemed keen to meet these beings form “outer space”, as noted by a person speaking in Gujarati: “Greetings from a human bing of the Earth. Please contact,” while others were perfectly happy for the extraterrestrials to stay put, thank you very much, as evidenced by the recording of a Rajasthani speaker: “Hello to everyone. We are happy here and you be happy there.” 3

2 Linguistic Society of America. www.lsad.org. Accessed on March 3, 2014.

3 Carl Sagan, Murmurs of Earth: The Voyager Interstellar Record (New York: Random House

Books, 1978), 125.

51

Figure 10: ENGINEERS ATTACHING The Sounds of Earth to Voyager I, 1977

52

Also included on one of the records, a message from then president Jimmy

Carter read:

This is a present from a small distant world, a token of our sounds, our science, our images, our music, our thoughts and our feelings. We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours. We hope someday, having solved the problems we face, to join a community of galactic civilizations. This record represents our hope and our determination, and our good will in a vast and awesome Universe.4

A list of “world music” 5 on the record included recordings of traditional

Indian vocal music, Javanese Gamelan, a Bach organ prelude, a Pygmy honey-gathering song, a track from John Coltrane’s Giant Steps, and an orchestral work by Debussy, performed by the New York Philharmonic

Orchestra. 6

Of course, should interstellar beings ever chance upon the Voyager craft,

“hear” the sounds, “read” the text, and understand the diagrams that point to planet Earth, they would find a very different world than the one that had been recorded in 1977.

4 Ibid,. 28.

5 Ibid,. 162.

6 Ibid,. 257.

53

Given the time and budget constraints and the political state of the world at the time, one can hardly fault Sagan for his Western-centric ambition to encapsulate and archive the entire world’s heritage on two phonographic disks. However, Sagan was well aware of the fragile human condition and the possibility that life as we know it might not exist anymore, but still conveyed his hope that despite all the problems and challenges related to the mission, these discs would carry with them a message of hope and optimism to whomever, or whatever might be beyond our own galaxy:

[…] perhaps the aliens would recognize the tentativeness of our society, the mismatch between our technology and our wisdom. Have we destroyed ourselves since launching Voyager, they might wonder, or have we ton on to greater things? 7

Limitations of the human brain may mean that we might never truly comprehend the true scale and magnitude of the universe, let alone imagine life beyond what Sagan refers to as the “Pale Blue Dot.”8 Perhaps, as

Richard Dawkins points out, it is exactly the vastness and endless expansion of the universe that will broadens our minds and captures our imagination, leading us further into discovery of who we are and perhaps to find life in other part of the universe:

Nothing expands the mind like the expanding universe. The music of the spheres is a nursery rhyme, a jingle set against the majestic chords of the Symphonic Galactica. Changing the metaphor and the dimension, the dusts of the centuries, the mists of what we presume to call ‘ancient’ history, are soon blown off by the steady, eroding winds of geological ages. Even the age of the universe […] is dwarfed by the trillenia that are to come. 9

7 Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan, Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space

(New York: Ballantine Books, 2011), 125.

8 Ibid., 34.

9 Lawrence Krauss, A Universe from Nothing: Why There Is Something Rather Than Nothing

(New York: Simon and Schuster, 2012), 187.

54

Figure 11: GOLDEN RECORD ON Voyager I, 1977

55

Figure 12:

Gulliver’s Travels -

VOYAGE TO LILLIPUT

When we gaze up at the stars, it seems almost impossible to assume that life beyond our planet might not exist. Despite advanced technologies of vision that have allowed us to peer deeper into the universe than ever before, human beings generally have had trouble imagining the existence of any other life forms besides their own.

The Russian Formalists were drawn to Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels for its broad use of defamiliarization as literary device. 10

Swift’s novel took many cues from numerous inventions of new technologies of vision that were being introduced at the time: telescopes, microscopes, and pre-cinematic devices produced optical shifts in human perception. From scenes where Gulliver is tied up by miniature Lilliputians to the ludicrous experiments performed by the scientists of Lagado, absurdism is used in the novel to defamiliarize the reader and help them see reality with new eyes.11

Sending all there is to know of the Blue Planet on a now defunct artifact into interstellar space might seem like a ridiculous proposition, but it is exactly in the absurdity of the endeavor that the viewers’ expectation of reality is destabilized as they reconsider their own surroundings and environment and might entertain the notion and possibility of the existence of other living beings many light years away.

10 Alan Wall and Goronwy Tudor Jones, Myth, Metaphor and Science (Chester: University

of Chester, 2009), 21.

11 Ibid., 22.

56

Figure 13:

Pioneer Plaque - ON BOARD THE VOYAGER

In Sounds of the Earth, defamiliarization takes place in the exaggeration of space and distance. Questions emerge: what would contemporary society choose to send into interstellar space as a record of human life today? How do we preserve the world’s heritage for future generations and other living entities without relying on technologies that will become obsolete? And finally, who gets to decide what should be preserved, how it is preserved, and where these records of our world heritage is sent?

Sounds of the Earth is at once a critique on humanity’s dependency on technology that will inevitably become obsolete, and a satirical account of our inability to envisage or locate the existence of life forms beyond our own.

57

Figure 14: For Marcel (2011) - DETAIL

F O R M A RC EL

One way to write music: study Duchamp.

Say it’s not a Duchamp.

Turn it over and it is.

J O H N CAG E

Besides, you know, all my work, literally and figuratively, fits into a valise….

M A RC EL D U C H A M P

59

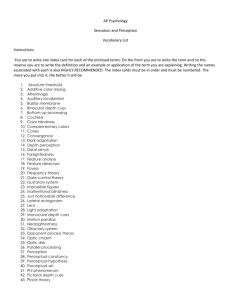

F O R M A RC EL

(2011)

Sound Installation

Materials: Telephone chair, PA speaker system, foam, speaker drivers, antique phone,

CD player, blue & amber light

Dimensions: 3’h x 3’-6” w x 2’-3”d

P RO J E C T D ES C RI P T I O N

For Marcel, is a responsive two-channel sound installation that pays tribute to the legacy of Marcel Duchamp, the Dada movement, and the music of

John Cage. Cage’s score, titled For Marcel Duchamp, is a 5-minute work for prepared piano that he wrote specifically for a sequence featuring Marcel

Duchamp in Hans Richter’s film Dreams That Money Can Buy.

From one channel, the composition of Cage can be heard: pieces of rubber, weather stripping and a small bolt are placed on the strings to emphasize the high frequencies and harmonics of the piano. Two distinct melodies and the sound of an occasional high-pitched tone from the bolt, are supported by a soft, sustained pedal, creating a subdued, mysterious atmosphere. From the other channel, a re-sampled recording of Duchamp being interviewed by an art critic can be heard.

For Marcel occupies a space somewhere between sculpture, composition, remix, and installation. The conversation between Duchamp and the interviewer, accompanied by Cage’s fragmented piano composition, mimics the artists’ playful critique of the art world and their interest in the deconstruction of visual and sonic art.

60

Figure 15: For Marcel (2011) - INSTALLATION VIEW

The viewer sits on a telephone chair — a functional piece of furniture commonly found in twentieth century households that has all but lost its function in society today. A retrofitted telephone from the same period, reflects Duchamp’s sense of irony, humor and ambiguity in an object that is decidedly recognizable, yet wholly impractical in modern times.

From the inverted telephone, a two-channel sound score emanates from small, metallic tweeters. The voice of Duchamp, merged with the score from John Cage, create an imaginary cinematic effect as the listener starts to perceive a dialogue between the voices and the sound score.

The use of blue and amber light envelopes the sculpture in an environment that implies a theatrical rendering of the space of an imaginary, staged script between Cage and Duchamp.

61

S C RI P T

DUCHAMP: I don’t care whether I am or not…

What I am, in fact, I don’t care.

And I doubt the word “be”…

INTERVIEWER: Ironically, causality is one of the techniques by which you make decisions, the conceptual decisions that you make.

… is it a joke?

D: Yes…it is a joke all right.

But it’s based on the fact that I have my doubts about real causality.

What is the real reason for using causality?

Why not use it ironically by inventing a world in which things come out differently than what they really are?

Imagine a new causality in which you invent your reasons for this or that.

pause…

D: Don’t you think so?

I: What is the concept of anti-art to you?

D: I’m against the word anti.

Because it functions like the word atheist as compared to believer.

And an atheist is just as much a religious man as the believer is.

And an anti-artist is just as much a believer as the other artist.

(an)artist would be much better if I could change it.

Meaning, no artist at all.

62

Figure 16: JOHN CAGE - PREPARED PIANO

63

Figure 17: Chauvet CAVE DRAWING.

H uman desire to represent the world around them for future generations dates back to the Paleolithic era. For cave dwellers, fire became a double-edged illumination device: its amber would become the charcoal used for sketching, while the glow of the flame threw light on the drawings etched onto the dark cave walls.

In the recently discovered Chauvet Caves in Pont d’Arc in Southern

France, cave paintings dating from the Upper Paleolithic age show the cave dwellers’ attempt to freeze time in representations and imagery. In

Cave of Forgotten Dreams, Werner Herzog elaborates on one particular drawing in the cave. Repetitive lines drawn with black charcoal reveal a five-horned rhinoceros, suggesting the animal’s movement through time, indicating of “a form of proto-cinema.”1

1 Werner Herzog, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, DVD, directed by Werner Herzog.

(2010; Paris: Creative Differences)

64

Herzog suggests another cinematic link as he re-enacts the flickering of the flames from a torch on the walls of the cave. Outside, the landscape belies the violence, danger, and fear that these early humans must have experienced as they shared the land with their predatory neighbors. Herzog connects the inner cave depictions to more contemporary representations of landscape and memory:

There is an aura of melodrama in this landscape. It could be straight out of a Wagner opera or a painting of German

Romanticists. Could this be our connection to them? This staging of a landscape as an operatic event does not belong to the Romanticists alone. Stone Age men might have had a similar sense of inner landscapes. 1

The desire to represent these inner landscapes would persist through the history of human vision. Every new technology would carry forth new modes of representation and perception. Traveling long distances at great speed on the newly built railroads and trains in the early nineteenth century would reshape the temporal and spatial experience of the passengers.

Looking out of the compartment window of a train embodied the perspective of modern perception as the “railroad choreographed the landscape,” rendering the landscape as fragmented impressions and moving images.2

From pre-cinematic devices to the high definition cinematic tools of today, technologies of representation are machines of narration that archive memories, and capture human hopes, ideas, and ideals. They re-frame the body: our sense of space, time, and distance is changed. When we sit in front of a screen, we might feel that we have become passive spectators, but whilst our bodies are immobile, our imagination drifts freely:

The (im)mobile film spectator moves across an imaginary path, traversing multiple sites and times. Her navigation connects distant moments and far apart places.3

1 Ibid.

2 Anke Gleber, The Art of Taking a Walk: Flanerie, Literature, and Film in Weimar Culture

(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999), 38.

3 Giuliana Bruno, “Site-seeing: Architecture and the Moving Image,” http://www.pitzer.

edu/academics/faculty/lerner/wide_angle/19_4/194bruno.htm

65

M I RRO R F O R LAT EN C Y

We have lived once in a world where the realm of the imaginary was governed by the mirror, by dividing one into two, by otherness and alienation.

Today that realm is the realm of the screen, of interfaces and duplication, of continuity and networks. All our machines are screens, and the interactivity of humans has been replaced by the interactivity of screens.

J E A N BAU D RI LLA RD

X e rox a n d I n fi n i t y, 1 9 6 8

Figure 18: Mirror for Latency INSTALLATION VIEW

67

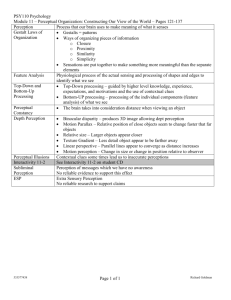

M I RRO R F O R LAT EN C Y

(2014)

Sound Installation

Materials: Wood, mirrors, microphones, headphones

Dimensions: 10’ w x 1.5’ h x 2’ d

P RO J E C T D ES C RI P T I O N

Mirror for Latency is a sound installation that recreates latency of networked communication in an unexpected environment. Viewers sit opposite each other and look into a 7’ wooden box. Inside, three mirrors are angled in such a way that each viewer sees the inverted visage of each other.

Using headphones and a microphone on each end, the voices of the participants are affected by sound manipulation software. Frequency, amplitude, and voiced sounds are used, along with other effects to intervene in the re-synthesis of the voices, creating distance between the viewers whilst also a sense of disembodiment.

Speaking to each other into headphones creates a sense of intimacy, yet the discombobulated and delayed voices of the opposing viewers create a confusing sense of space and time.

68

Figure 19: Mirror for Latency INSTALLATION VIEW

Figure 20: Mirror for Latency RENDERING

69

C onnectivity provokes intensive space-time: hyper-speed in hyper-space. We have become particles of a network. Real-time connectedness on an always-on virtual network shapes new kinds of relationships whilst weakening more traditional social bonding structures.

As a sound piece, Mirror for Latency exists in a shared moment between two viewers seated opposite each other. The objective, upside-down reflection of the mirrors with the digitally processed sound score destabilizes the viewers’ perception of each other.

In medicine and physiology, a “latent period” refers to the delay between the receipt of a stimulus by a sensory nerve and the brain’s response to it. 1

In a technical, information-communication environment, latency refers to the delay period between parties communicating over a network.

We have become accustomed to a feeling a sense of disembodiment when we communicate over a network and have become accustomed to a certain level of latency in an online exchange. Mirror for Latency approaches and reveals the circumstances and nature of communication that is usually experienced in a virtual environment and reproduces similar sensations in a real, physical environment.

Mirrors become the transducer that facilitates communication. Digital screens have a similar function. In Mirror for Latency the screen has all but lost its shape and instead functions as a post-cinematic, phenomenotechnical device used to invoke a non-normative environment.

1 “Phosphene” Oxford English Dictionary, on-line edition. Oxford, accessed March 30,

2014.

70

Our eyes describe, record, and catalog new discoveries, narratives, and endeavors of human experience in history. For Plato, vision is humanity’s gift to a greater understanding of the Universe itself:

Vision, in my view, is the cause of the greatest benefit to us, inasmuch as none of the accounts now given concerning the

Universe would ever have been given if men had not seen the stars or the sun or the heaven. 2

Technologies of vision have the power to alter human perception and with each new invention we are confronted with a new way of thinking, a different way of “being-in-the-world,” new structures of “material investment,” and new “aesthetic responses and ethical responsibilities.” 3

Knowledge of the mechanism of the camera obscura — light passing through a small hole into a dark interior produces an inverted image

— has been available for the past two thousand years to thinkers and philosophers like Euclid, Aristotle, and da Vinci.

2 Donald, Zeyl, Plato: Timaeus (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., 2000), section 47(a).

3 Vivian Sobchack, The Scene of the Screen: Envisioning Cinematic and Electronic ‘Presence’ in Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht and K. Ludwig Pfeiffer (ed), Materialities of Communication

(Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1994), 84.

71

Figure 20: CAMERA OBSCURA

A quick comparative glance at the mechanism of the camera obscura, the camera, the human eye, and optics in general scientific studies may account for the many histories of photography and cinema that repeat a similar narrative: photography, and subsequently the invention of cinema is a direct consequence of the invention of the camera obscura. However,

Jonathan Crary warns against the problematic comparison of the reflection of the camera obscura, and that of the photo camera or the human eye, outlining the challenging complexities of the subjectivity of the observer’s eye compared to the objective reflection of the camera obscura:

I argue that the camera obscura must be understood as part of a larger organization of representation, cognition, and subjectivity in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries

[…] which is fundamentally discontinuous with a nineteenth-century observer. Thus I contend that the camera obscura and photography, as historical objects, are radically dissimilar. 4

4 Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer. October, Vol. 45 (Summer, 1988): 32.

72

For scientists and artist of the seventeenth and eighteenth century, the camera obscura guaranteed an objective reflection of the world. However, contemporary society has accepted that truth in image today is a fallacy.

Awareness of human apprehension of the world around them through the senses — whether hearing, touch, smell, and taste — have preoccupied philosophers for a very long time. Philosophical accounts of vision go back as far as Plato, who describes the false sense of truth from sight in his Allegory of the Cave. Trapped inside a cave, the prisoners see shadows cast upon the interior walls of the cave, illusions they perceive to be real. But what the prisoners are really perceiving, are only appearances of images, not truths.

Almost 2,500 years later, Susan Sontag would reflect on Plato’s allegorical tale in her treatise On Photography, reminding us that photographs are still only reflections of what is reality:

Humankind lingers unregenerately in Plato’s cave, still reveling, its age-old habit, in mere images of the truth.5

Still, the screen remains a moment of reflection. It interrupts. It reflects back to us. Sometimes, we are able to reach through the screen as we connect with each over a network and over long distances. The reflection has gone digital.

5 Sontag, Susan, On Photography (New York: Picador USA : Farrar, Straus and Giroux,

2001), 5.

73

Figure 21: Plate No. 32 Optics. illustrations referring to a range of scientific diagrams and to popular knowledge on the general topic of optics.

74

The prefix of interface indicates a linkage: in-between, among, or even mutual. Its root, “face” from Latin facies, refers to a surface, front, or visage.6

The etymology of the term interface arose in Victorian-era scientific experiments in fluid dynamics, migrating to nineteenth century classical mechanics, telegraphy, and thermodynamics. In their study of electromagnetism, nineteenth century scientists posited that light needed to travel in a substance — a light- and energy-bearing ether — or what they called the “luminiferous ether.” 7 James and William Thomson would introduce the term interface in a series of lectures in an effort to explain how stars reflect light to the earth, describing this ether as the “matter between us and the remotest stars” concluding that “the luminous enter on two sides of the interface at which the refraction and reflection takes place, might differ both in rigidity and in density” 8

The belief amongst the academic community that light passed through an intangible and invisible “skin” or layer was commonplace until Einstein shook the foundations of physics with his theory of special relativity in

1905. Following this paradigm shift in the scientific community, it was no longer believed that some type of physical matter needed to exist for energy to travel. However, William Thomson would again refer to the term

“interface” at a later stage when he worked some of the first transatlantic cables. 9

6 “Visage.” Oxford English Dictionary, on-line edition. Oxford, accessed March 10, 2014.

7 Peter Schaefer, Interface: History of a Concept, 1886 -1888, in The Long History of New

Media (New York: Peter Lang International, 2011), 173.

8 Ibid., 173.

9 Ibid., 173.

75

Sixty years later, early main-frame computers still lacked any form of interface, but by the late twentieth century, the interface became the space of interaction between humans and machines.

Today, the interface is arguably one of the predominant points of human contact with machines. No longer just viewers, we have become users of streaming data — images, information, and digital content. The relationship between body and technology has become progressively dualistic as our bodies are situated — motionless — in front of these screens.

This perpetual mediation and its effect on human relationships with each other, technology and the world around them has not gone unnoticed. Several thinkers, writers, and theorists have studied the effects of constant mediation. Marshall McLuhan’s object-centered approach interprets media objects as technological extensions of the human body: “… the wheel is an extension of the foot, the book is an extension of the eye, clothing an extension of the skin, electric circuitry, an extension of the central nervous system.” 10

Friedrich Kittler’s observation of media objects was that they carry their own technological logics, whilst only intersecting obliquely and occasionally with human perceptions. Kittler claims that media such as radio, cinema, and television change our sense of space, time, and social relationships; they condition human experiences and perceptions, and that “media determine our situation.” 11

In The Interface Effect, Alexander Galloway takes a different philosophical approach, including thinkers such as Heidegger, and views techne as

“technique, art, habitus, ethos, or lived practice.” In this view, media are not “objects or substrates” but rather “practices of mediation.” 12

The interface is not a surface, nor a mirror or an extension of any human faculty (psychic or physical), but rather an interstitial space — facilitated by hardware — allowing for translation between different states: virtual to real, material to immaterial, and human to machine.

10 Marshall McLuhan, and Quentin Fiore, The Medium Is the Massage (Corte Madera:

Gingko Pr., 2001), 26.

11 Friedrich Kittler, Gramophone, Film, Typewriter (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press,

1999), xxxv.

12 Alexander R Galloway The Interface Effect Cambridge (UK: Polity, 2012), 16.

76

Figure 22: IBM “MAINFRAME” (1964)

Figure 23: Skinput - MICROSOFT RESEARCH LAB (2014)

77

S COR E F OR R HOMB I WALL

… in looking at an object, we reach out for it. With an invisible finger we move through the space around us, go out on the distant places where things are found, touch them, catch them, scan their surfaces, trace their borders, explore their texture. It is an eminently active occupation.

R U D O LF A RN H EI M

A r t & V i s u a l Pe rc e p t i o n

Figure 24: Score for Rhombi Wall - INSTALLATION VIEW

79

S CO RE F O R RH O M B I WA LL

(2012)

Experiential Sound & Moving Image Installation

Materials: Projection, custom-made goggles, sound

Dimensions: Variable

P RO J E C T D ES C RI P T I O N

Score for Rhombi Wall is a temporary, computer-augmented, and modular light sculpture that reflects on the temporal quality of light and its perpetual transformation in space through the articulation of light and shade.

Using the projector beam as a light source, and applying the shape and contour of light on the forms through the use of video mapping, the sculpture presents two levels that explore different aspects of spatio-temporal reality: the first level consists in a physical volume that controls real space and acts as a support for the second level, consisting of a virtual layer of projected light that permits the viewer to experience and control the transformation and sequencing of the light, color and contours of the sculpture.

Artificial, extruded light moves and passes over a matrix of rhombi structures: darkness and illumination alternate, creating an unlimited variety of possible spatial sequences. Through live manipulation of video, different configurations of light situations are created that produce contrasting moments of intensity, depth, and movement. The viewer is confronted with a meta-surface: a polymorphous, playful space in continuous transformation.

80

Figure 25: Score for Rhombi Wall - CONSTRUCTION

Figure 26: Score for Rhombi Wall - INSTALLATION VIEW

81

S core for Rhombi Wall is an experiment in material imagination, visual illusion of space and depth, and the explicit and implicit perception of figure and ground. Relying on the ephemerality of light, tension between contrasting hues, and the rhythmic possibilities of repetitive patterns in movement, the aim of this sculpture is to probe and alter the viewers’ perceptual processes related to the experience of surface and space.

Vividly colored light emanating from a video projector is guided and traced onto the sculpture through the use of video mapping: a projection technique that takes the beam from a projector and re-configures the shape of the projected light to fit forms and spaces of interior- and exterior architecture. This technique allows for virtually any surface to become a screen, and to create depth on a flat surface by projecting three-dimensional content. Through a combination of consistent geometric vocabulary and slow-moving light, Score for Rhombi Wall creates a trompe l’oeil effect, challenging the viewer’s sense of depth, casting the viewers’ stability of perception into question.

There is no precise English equivalent for the Dutch verb tasten, a word that could be compared to “groping,” or the “searching movement of the hands when it is dark.”1 Thinking — translated into Dutch as denken — and feeling without seeing denotes a type of perceptual comprehension that is “fragmentary” and “uncertain about its direction,” but “in close contact with what it thinks about and even assuming the form of what it holds.”2

1 Renée van de Vall, At the Edges of Vision: A Phenomenological Aesthetics of Contemporary

Spectatorship (Burlington: Ashgate, 2008), 5.

2 Ibid,. 5.

82

Today, we navigate screens by interacting with icons behind glass screens.

These so-called touch screens are designed with the promise of providing tactile feedback3, but as Bret Victor points out, human interaction with “pictures under glass” 4 reduces the dexterity of the human hand to a glorified point-and-click action:

Hands do […] utterly amazing things, and you rely on them every moment of the day [...] There’s a reason that our fingertips have some of the densest areas of nerve endings on the body. This is how we experience the world close-up. This is how our tools talk to us. The sense of touch is essential to everything that humans have called ‘work’ for millions of years.

[...] claiming that Pictures Under Glass is the future of interaction is like claiming that black-and-white is the future of photography. It’s obviously a transitional technology. And the sooner we transition, the better. 5

Using body-location, perceptual play — configuration of perceptual disparities, aberrations and illusions — and eye-movement to create interactivity in the work, Score for Rhombi Wall offers no specific object for the viewer to interact with. Rather, the scope of interactivity is expanded by using the orientation, movement, and placement of the body in relation to the installation itself.

Viewers experience an unsettling feeling — light and shadow create a false sense of depth — and they are provoked to readjust their expectations of the materiality, shape, and texture of the surfaces. This feeling of uncertainty often prompts viewers to move closer to the sculpture and to touch the surface of the shapes in an effort to establish its material quality.

3 Alberto Gallace and Charles Spence, In Touch with the Future: The Sense of Touch from

Cognitive Neuroscience to Virtual Reality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 215.

4 “A Brief Rant on the Future of Interaction Design,” Bret Victor, accessed April, 24, 014, http://worrydream.com/ABriefRantOnTheFutureOfInteractionDesign

5 Ibid.

83

Figure 26: Score for Rhombi Wall - INSTALLATION VIEW

84

Figure 27: Score for Rhombi Wall - INSTALLATION VIEW

85

F LO O D

Color is energy made visible.

J O H N R U S S ELL

T h e E m a n c i p a t i o n o f C o l o r, 1 9 7 5

But to determine more absolutely, what Light is . . . not so easy.

I S A AC N EW TO N

O p e r a Q u a e E x t a n t O m n i o a , Vo l . I V, 1 7 8 2

Figure 28: Flood - INSTALLATION VIEW

87

F LO O D

(2014)

Experiential Sound & Moving Image Installation

Materials: Projection, custom-made goggles, sound

Dimensions: Variable

P RO J E C T D ES C RI P T I O N

Viewers wear custom-made spectacles made from acetate projector film, and are seated approximately 7 feet from a large screen, where they view a succession of luminous planes of color beaming from an overhead projector.

Colors flicker and vibrate at various speeds, accompanied by a soundtrack composed of sine-wave frequencies.

The ganzfeld effect is designed to be experienced in a quiet space with no sound or other sensory stimuli. Research showed that when the participants were immersed in an environment of total sensory deprivation, they would be more likely to experience hallucinations.

In Flood, the addition of an additional sensory activity denies the viewer any hallucinatory experiences, instead bringing the viewers’ attention to the physiological experience of the perception of color. Changing hues are experienced as energetic pulses that can be felt through the eyes.

88

Figure 29: Flood - INSTALLATION VIEW

89

S ome of the earliest research and experiments in sensory deprivation took place in the early 1950s at McGill University. Scientists involved in the research showed that the loss of depth perception — therefore an absence of change in the brain — caused a lapse of attention, and perceptual aberrations.1

In Notes Toward a Conditional Art, Robert Irwin explains how change in the brain becomes a basic function of the perceptual process:

Change is the most basic condition (physic) of our universe.

In its dynamic, change (alongside time and space) constitutes a given in all things, and is indeed what we are talking about when we speak of the phenomenal in perception […]

No change, no perceptual consciousness.2

In the McGill University research, the hallucinations stemming from prolonged sensory deprivation would range from very simple, to complex.

One of the researchers detailed the wide range of illusionary sensations experienced by some of the participants:

In the simplest form the visual field, with the eyes closed, changed from dark to light color; next in complexity were dots of light, lines, or simple geometrical patterns… Still more complex forms consisted in “wall-paper patterns,” …

Finally, there were integrated scenes … frequently including dreamlike distortions, with the figures often being described as “like cartoons.” 3

1 Oliver Sacks, Hallucinations (Waterville: Vintage, 2013), 49.

2 Robert, Irwin, Notes toward a Conditional Art (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011), 202.

3 Ibid.,41.

90

Figure 30: James Turrell and Robert Irwin conducting a sound and light experiment in an anechoic chamber

Flood revisits the perceptual experiments investigated by James Turrell and

Robert Irwin during their collaboration for the “Art & Technology” initiative at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in 1969.

In collaboration with Ed Wortz, an experimental psychologist from the

Garrett Corporation, Turrell and Irwin worked together on sensory deprivation experiments, in an effort to discover “man’s sense of his environment, and particularly his perceptual sense of that environment.” 4

Turrell and Irwin took extensive notes in a detailed report titled Report

on the Art and Technology Program, detailing the main objective of their collaboration:

Allowing people to perceive their perceptions — making them aware of their perceptions. We’ve decided to investigate this and to make people conscious of their consciousness […]5

4 Lawrence Weschler, Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees (Berkeley:

University of California Press, 2009), 127.

5 Ibid,. 127.

91

Irwin and Turrell proposed a light and sound piece that would study human sensory thresholds and would give members of the public an opportunity to experience ganzfeld in a controlled environment. Irwin described their Gans Fields as: “360 degrees of homogeneous color … which afford(s) the sensation one might experience sticking one’s head inside a giant, evenly lit Ping-Pong ball.” 6

After some test experiments, Irwin described the sensation felt after having experienced a period of total sensory deprivation in the anechoic chamber:

[…] when you came out of that anechoic space, having a slightly altered sense of threshold and sense dependence, you simply did not construct the world in the same way: it actually was made up of a different kind or amount of information.7