Comparative mapping in intraspecific populations uncovers a high degree of macrosynteny

advertisement

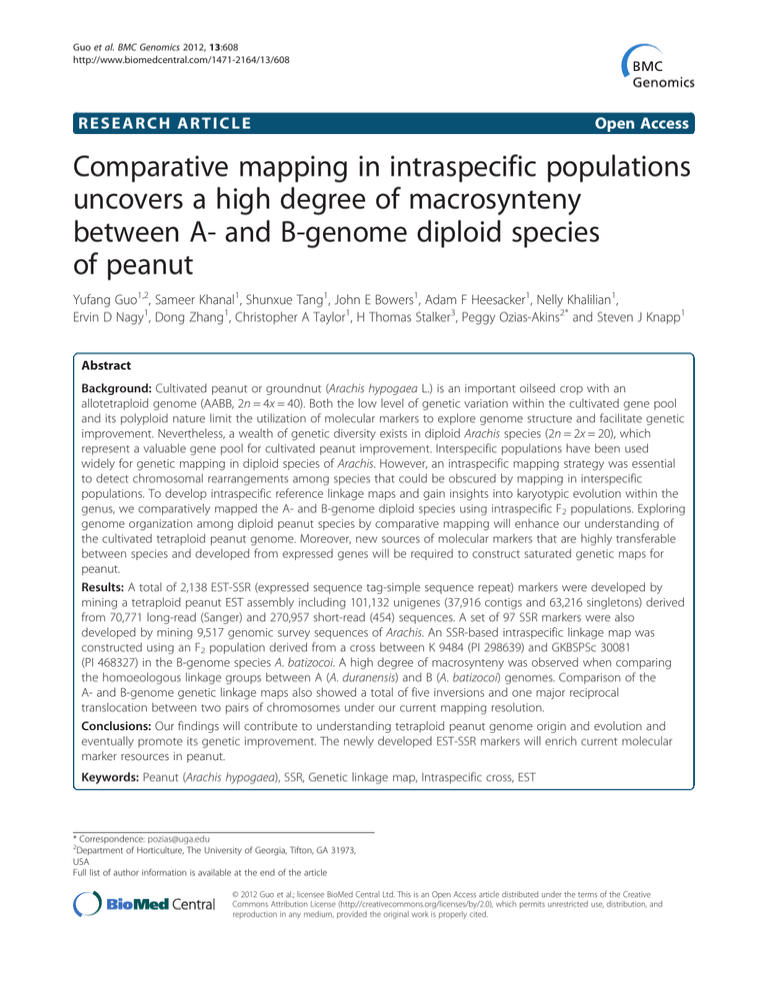

Guo et al. BMC Genomics 2012, 13:608 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/13/608 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Comparative mapping in intraspecific populations uncovers a high degree of macrosynteny between A- and B-genome diploid species of peanut Yufang Guo1,2, Sameer Khanal1, Shunxue Tang1, John E Bowers1, Adam F Heesacker1, Nelly Khalilian1, Ervin D Nagy1, Dong Zhang1, Christopher A Taylor1, H Thomas Stalker3, Peggy Ozias-Akins2* and Steven J Knapp1 Abstract Background: Cultivated peanut or groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) is an important oilseed crop with an allotetraploid genome (AABB, 2n = 4x = 40). Both the low level of genetic variation within the cultivated gene pool and its polyploid nature limit the utilization of molecular markers to explore genome structure and facilitate genetic improvement. Nevertheless, a wealth of genetic diversity exists in diploid Arachis species (2n = 2x = 20), which represent a valuable gene pool for cultivated peanut improvement. Interspecific populations have been used widely for genetic mapping in diploid species of Arachis. However, an intraspecific mapping strategy was essential to detect chromosomal rearrangements among species that could be obscured by mapping in interspecific populations. To develop intraspecific reference linkage maps and gain insights into karyotypic evolution within the genus, we comparatively mapped the A- and B-genome diploid species using intraspecific F2 populations. Exploring genome organization among diploid peanut species by comparative mapping will enhance our understanding of the cultivated tetraploid peanut genome. Moreover, new sources of molecular markers that are highly transferable between species and developed from expressed genes will be required to construct saturated genetic maps for peanut. Results: A total of 2,138 EST-SSR (expressed sequence tag-simple sequence repeat) markers were developed by mining a tetraploid peanut EST assembly including 101,132 unigenes (37,916 contigs and 63,216 singletons) derived from 70,771 long-read (Sanger) and 270,957 short-read (454) sequences. A set of 97 SSR markers were also developed by mining 9,517 genomic survey sequences of Arachis. An SSR-based intraspecific linkage map was constructed using an F2 population derived from a cross between K 9484 (PI 298639) and GKBSPSc 30081 (PI 468327) in the B-genome species A. batizocoi. A high degree of macrosynteny was observed when comparing the homoeologous linkage groups between A (A. duranensis) and B (A. batizocoi) genomes. Comparison of the A- and B-genome genetic linkage maps also showed a total of five inversions and one major reciprocal translocation between two pairs of chromosomes under our current mapping resolution. Conclusions: Our findings will contribute to understanding tetraploid peanut genome origin and evolution and eventually promote its genetic improvement. The newly developed EST-SSR markers will enrich current molecular marker resources in peanut. Keywords: Peanut (Arachis hypogaea), SSR, Genetic linkage map, Intraspecific cross, EST * Correspondence: pozias@uga.edu 2 Department of Horticulture, The University of Georgia, Tifton, GA 31973, USA Full list of author information is available at the end of the article © 2012 Guo et al.; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Guo et al. BMC Genomics 2012, 13:608 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/13/608 Background Peanut or groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) is both an important oilseed crop and a direct protein source for human nutrition and is the only domesticated species in the genus Arachis. It is an allotetraploid (2n = 4x = 40, AABB) with one pair of distinctively small chromosomes [1], and was believed to have originated from a single hybridization event at least 3,500 years ago [2-4]. This genus also contains additional tetraploid, diploid (2n = 2x = 20) and aneuploid (2n = 2x = 18) species. Arachis hypogaea is a member of section Arachis, which contains species with A, B, or D genomes. The Arachis genome is characterized by the presence of a small pair of chromosomes with a lower level of euchromatin condensation [5], whereas the B genome is distinguished by the presence of a pair of chromosomes with a secondary constriction proximal to the centromere [6], and has recently been divided into subgroups [7]. Arachis duranensis and A. ipaënsis are most likely the ancestral A- and B-genome species of cultivated peanut, respectively [2,5,8-10]. The D genome is represented by the single species A. glandulifera [11,12]. Due to both the low level of genetic variation within the cultivated gene pool and the polyploid nature of cultivated peanut, relatively fewer numbers of genetic linkage maps have been constructed as compared to many other crop species [13]. Considering its relatively large genome size (2800Mb/1C), there is still great need to improve marker density and genome coverage [14,15]. For example, mapping of quantitative trait loci (QTL) for late leaf spot, rust [16] and seed quality [17] traits has only been possible at low marker density with 225 and 45 SSR loci, respectively. A wealth of genetic diversity exists in diploid Arachis species [18] with the potential to introgress novel alleles into cultivated peanut [4,19]. The diploid wild species are not commercially important in the food industry, but they provide a valuable gene pool for sources of resistance to many economically important pathogens and pests [20-23]. Several linkage maps have been constructed in both A- and B-genome diploid species [24-28], with the first A-genome linkage map reported being composed of 11 linkage groups with 117 RFLP loci and with a genome coverage of 1,063 cM [26]. Subsequent A-genome linkage maps consisted of 167 RAPD and 39 RFLPs, 170 SSR, or 369 assorted markers [25,27,28]. An interspecific Bgenome linkage map has been constructed with 149 SSR loci covering 1,294 cM [24]. Synteny between A and B genomes was compared using diploid as well as synthetic amphidiploid linkage maps [24,29,30]. The above-referenced diploid linkage maps were generated from interspecific crosses. Thus, the detection of chromosomal rearrangements within species could be obscured, and comparative A- and B-genome linkage Page 2 of 12 maps could be complicated due to chromosomal rearrangements associated with speciation [31-35]. Previous comparisons were based on limited numbers of orthologous loci and markers that were primarily derived from genomic sequences. Therefore, map coverage and resolution need to be improved using more function-related and highly transferable markers such as EST-SSRs that facilitate comparative and evolutionary genomics studies. To enrich the currently available SSR marker resources in peanut and gain clearer insights into karyotypic evolution within the genus, a new set of EST-SSR markers was developed and mapped in an intraspecific B-genome mapping population. Comparative mapping to intraspecific A-genome linkage maps revealed a high degree of macrosynteny. Results and discussion Marker development A total of 101,132 unigenes representing ca. 37 Mb of the A. hypogaea genome (Additional file 1) were mined for SSRs. We found 7,413 perfectly repeated di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, and hexa-nucleotide motifs (7.3% of the unigenes contained SSRs). The SSR frequency in the above EST resources is comparable with previous reports in cultivated peanut [36,37], and wild Arachis species [38]. The overall SSR density was 3,190 bp per Mb and corresponded to approximately 1 per 5 kb of the genic region, which is similar to a previous report of 1/5.5 kb in cultivated peanut [15]. higher than Arabidopsis [39], and barley [40] but slightly lower than that reported for rice [41] and pepper [42], yet within the range of most other plant species (~5%) [43]. The average SSR length was about 16 bp with almost 88% of SSRs shorter than 22 bp. Among repeat motifs, dinucleotides were predominant (53.3%), which was inconsistent with the study of Koilkonda et al. [15], who found trinucleotide repeats to be the most abundant (66.8%). Discrepancies observed in various studies could be explained by the degree of representation of dinucleotide rich UTRs in the genic sequences used or by EST database mining software and SSR search criteria [43]. Dinucleotide repeat motifs were predominantly distributed in the UTRs while trinucleotide repeat motifs were more frequent in exons. Considering the mode of slippage-mediated mutations, it is unlikely that a large proportion of the dinucleotides would be present in the coding regions; mutations in trinucleotides or their multiples would only be tolerated if they do not disturb the open reading frame. In our study, the most common dinucleotide repeat motif class was (AG)n (61.0%), while the least common repeat class was (CG)n (1.2%). Similarly, the most abundant trinucleotide motif class was (AAG)n (35.2%), and the least frequent was (CGA)n (0.9%). Motif classes Guo et al. BMC Genomics 2012, 13:608 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/13/608 Page 3 of 12 5), which was supported by the previous observations of Moretzsohn et al. [25]. For example, SSRs with a repeat length >26 bp showed up to 30% polymorphism between the four tetraploid genotypes, while less than 15% polymorphism was observed for SSRs with repeat length <20 bp. However, when all eight genotypes were combined, no trends were observed between the polymorphism and repeat length. For tetraploid genotypes, AG/CT repeats were more polymorphic than GT/CA, while in diploid genotypes, this effect can only be observed between interspecific genotypes in spite of the fact that the polymorphisms among four diploid genotypes were overall high (around 70%) (Table 1). Similar observations that AG/CT repeats were more polymorphic than GT/CA were previously reported in peanut [25,36,48]. The polymorphisms for dinucleotide repeat motif types were generally higher than for trinucleotide repeat motif types. However, no consistent pattern emerged for ranking of polymorphism rate by motif type. In addition to ESTs, a total of 9,517 genome survey sequences (GSSs) representing ca. 5.5 Mb of the Arachis genome were mined for SSRs. Overall, 1,168 perfectly repeated di-, tri-, or tetra-nucleotide motifs were identified from 960 unique sequences. By SSCP screening, 97 SSR primer pairs can produce reliable amplification across a panel of 12 genotypes representing different species (Additional file 6). (CG)n and (CGA)n are also relatively infrequent in other plants as well as animals [44]. The motif types (AG)n and (AAG)n have been reported as the most common di- and tri-nucleotide repeats identified in other plant EST databases [43,45-47], including peanut (A. hypogaea) [15,30,37,40,48,49]. We designed 2,138 EST-SSR primer pairs from the identified SSRs (Additional file 2), with 94.6% of them targeted to amplify perfect repeats and over 70% of the primers targeted at trinucleotide motif types. By screening a panel containing eight genotypes, (Additional file 3), 15.3% of the 2,138 primer pairs didn't amplify any interpretable fragments, and 82.7% of them were fully transferable between tetraploid and diploid species. As expected, we observed a relatively higher transferability for EST-SSRs than for genomic SSRs; this is most likely due to greater sequence conservation within expressed regions among related species compared to non-coding regions [25,36,43,50,51]. The frequency of polymorphism among the four tetraploid genotypes was 11.2% and less than 10.0% between paired tetraploids. The polymorphism between two A. duranensis accessions was 41.9% while between two A. batizocoi accessions was 21.3% (Additional file 4). The polymorphisms for our intraspecific diploid mapping population parents were comparable to the previous reports of interspecific diploid mapping populations for EST-SSR markers [24,25,30]. We also observed that the polymorphism was higher in the Agenome species than in the B-genome species [52]. Our findings also support the general theory that the degree of polymorphism of the SSR marker increases with the total length of the repeat [25,53,54]. A positive correlation was observed between repeat length and polymorphism rate, but the trend seemed more obvious in tetraploid than in diploid genotypes (Additional file Genetic mapping Collectively, 2,138 newly developed EST-SSR primer pairs (Additional file 2), 97 genomic SSR markers developed from genome survey sequences and 612 genomic SSR primer pairs in the public domain (Additional file 7) were screened for polymorphisms between the parents Table 1 Effect of SSR repeat motif types on frequency of polymorphism among tetraploid and diploid genotypes Motif type No. of Between Tif-runner Between NC94022 Among four Between 30081 Between Grif Among four Among eight markers and GTC20 (%) and SunOleic (%) tetraploid (%) and 9484 (%) 15036 and diploid (%) genotypes PI 475887 (%) (%) GT/CA 285 8.1 2.7 10.8 21.6 51.4 75.7 AG/CT 37 16.8 14.0 24.2 32.3 57.5 70.2 78.4 73.0 AT 69 14.5 13.0 23.2 21.7 47.8 69.6 76.8 CG 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 CCG/CGG 41 2.4 2.4 4.9 7.3 29.3 56.1 61.0 ACC/GGT 149 3.4 3.4 5.4 19.5 39.0 67.8 73.2 ACG/CGT 55 3.6 0 3.6 14.5 27.3 60.0 67.3 AGC/GCT 52 0 1.9 3.8 11.5 25.0 59.6 65.4 AGG/CCT 107 3.7 1.9 6.5 10.3 26.2 55.1 65.4 AAC/GTT 141 5.7 5.0 9.2 17.0 43.3 70.2 78.7 AAG/CTT 519 5.4 4.8 9.6 24.5 39.1 66.5 74.2 ACT/AGT 130 2.3 3.8 6.2 12.3 34.6 63.8 73.1 ATC/GAT 127 5.5 5.5 7.9 13.4 39.4 67.7 75.6 AAT/ATT 168 6.0 3.6 6.0 20.2 44.6 70.8 79.2 Guo et al. BMC Genomics 2012, 13:608 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/13/608 Page 4 of 12 of an intraspecific A. batizocoi (BB, 2n = 2x = 20) F2 mapping population. Although A. ipaënsis is the more likely B-genome donor than A. batizocoi to tetraploid peanut species A. hypogaea [52,55,56], A. batizocoi retains a high level of similarity to the B subgenome of cultivated peanut [57]. For example, the F1 plant derived from crossing A. hypogaea by a synthetic amphidiploid (A. batizocoi × A. duranensis) produced bivalents, and a few F4 plants from this cross were even able to produce two-seeded pods [58]. Furthermore, a diversity study indicated that among all the B-genome species, A. batizocoi showed the second closest relationship to A. hypogaea, after A. ipaënsis [55]. Although the hypothetical B-genome donor A. ipaënsis was not used for linkage mapping in this report because only a single accession is available in the U.S. germplasm collection, our A. batizocoi intraspecific map should still provide a very close representation of the B-genome donor of tetraploid peanut. The screening of A. batizocoi accessions 9484 and 30081 produced 455 polymorphic EST-SSR and 171 polymorphic genomic SSR markers. After excluding makers with numerous and/or faint bands and abnormal segregation ratios (markers that showed extreme segregation ratios were assumed to be caused by loci with indistinguishable bands), a total of 481 markers were used for linkage map construction. Of these, 449 loci (including 347 loci from the newly developed EST-SSR markers, 14 loci from genomic SSR markers developed from GSS sequences, and 88 loci from the genomic SSR markers already reported [18,25,48,49,59-62]) were mapped into 16 linkage groups (LGs), 14 of which aligned with the 10 chromosome pairs of diploid peanut numbered according to colinearity with A. duranensis (A- genome) linkage groups from Nagy et al. [63]. The remaining two small linkage groups had no common markers with A- genome linkage groups, thus their chromosomal locations are unknown. Their lengths were 1.1 cM and 9.2 cM, respectively. One LG consisted of markers GM2227 and GM1611, and another LG was composed of markers GM1241 and GM748. Overall, the linkage map covered 1,278.6 cM, with marker densities ranging from 1.1 cM/locus in LG11 to 9.2 cM/locus in LG12, giving an average density of 2.9 cM/locus for the entire map (Table 2, Figure 1). The LGs ranged from 1.1 to 210 cM in length, and had two (4/9B.1, 4/9B.2, and the two linkage groups described above) to 80 (4/9B) marker loci. Gaps larger than 30.0 cM were observed only at the end of 1B (31.9 cM) and 8B (33.6 cM) (Figure 1). The number of linkage groups observed in this study is larger than the number of haploid chromosomes in the diploid species (n = 10), which may be due to insufficient markers for the chromosome coverage. Furthermore, since the B-genome linkage groups were named by comparing common markers to A-genome linkage groups, the chromosome location of some small linkage groups could not be identified if they lacked anchor markers. The map length was comparable to previously published diploid peanut genetic maps while the density was the highest among all B-genome linkage maps constructed to date [24-26]. This is by far the most saturated map Table 2 Number of loci, map length and density of each linkage group in the 9484x30081 map Linkage group Length (cM) No. of marker/LG Density (cM/locus) Number of distorted loci (α = 0.05) 1B 98.2 38 2.7 10 2B 138.3 35 4.1 1 3B 117.8 62 1.9 0 4/9B 209.9 80 2.7 1 4/9B.1 3.4 2 3.4 0 4/9B.2 8.6 2 8.6 0 4/9B.3 47.1 7 7.9 1 5B 114.8 52 2.3 0 5B.1 30.1 6 6.0 0 6B 164.2 44 3.8 1 7B 36.6 13 3.1 2 8B 185.1 60 3.1 0 8B.1 7.1 5 1.8 0 10B 107.1 39 2.8 2 LG11 1.1 2 1.1 0 LG12 9.2 2 9.2 0 Whole map 1278.6 449 2.9 18 (4.0%) Guo et al. BMC Genomics 2012, 13:608 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/13/608 1A 9.3 13.6 16.9 18.9 20.4 21.0 24.4 26.3 26.7 29.8 37.6 38.0 38.5 38.9 39.2 39.4 39.6 39.8 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.5 41.1 41.6 42.0 42.8 43.8 45.7 47.2 47.5 47.9 49.8 50.0 50.2 50.4 50.5 50.6 50.7 50.8 51.0 51.1 51.4 51.7 52.0 52.6 54.1 54.2 54.7 55.7 59.4 61.0 63.6 64.5 66.6 76.6 76.7 77.9 87.9 91.4 1B GM1612 GM1750 GM2344 GM1085 GM1277 GM1620GM1275 GM38 GM1573 GM2053 GM2653 GM2061 GM1684 GM2004 GM1871 GM2132 GM2418 GM1599GM1542 GM1501 GM2350 GM1771 GM1913GM2349 GM2783 GM1879 GM2390 GM1950 GM2724 GM1444 GM933GM1339 GM1330 GM1353 GM1065 GM2840 GM1777 GM286 GM824 GM672 GM1048 GM2287GM1972 GM1233GM2527 GM1992 GM1649 GM22GM2597 GM890 GM1171 GM2015 GM917 GM170 GM2607 GM2233 GM2153 GM2173 GM1483 GM1423 GM2024 GM2603 GM1208 GM1132 GM2568 GM1504 GM2022GM1761 GM1118b GM1331 GM825GM1030 GM24 GM1661 GM1992 0.0 1.1 GM2602GM1725d GM2037 GM1725a GM1401 GM1182 GM1409 GM2565a GM475 GM24 GM2171GM1845 GM110aGM187 GM2606GM499 GM2122 GM2654 GM1610 GM443 GM1612 GM496 GM2344 GM529 GM2653GM1085 GM635 GM2132 GM1501 GM841 GM1849 GM2350 GM1290 GM1444 GM933GM1339 33.0 34.6 35.4 40.1 41.7 47.7 48.8 54.8 59.7 62.4 63.5 67.1 67.7 68.9 69.4 70.5 76.0 78.7 82.5 84.6 86.3 91.9 98.2 10A 0.0 1.9 18.6 26.8 26.9 29.7 38.4 43.2 44.5 46.0 46.6 49.0 50.1 50.6 51.1 51.5 51.6 51.7 51.8 52.0 52.3 52.6 52.9 53.9 55.1 58.4 58.9 59.9 62.1 63.0 64.9 66.0 67.0 69.5 70.6 73.0 78.5 79.1 79.4 84.7 89.0 92.2 97.3 100.2 101.1 101.3 101.8 103.9 104.7 110.2 2A 10B GM2032 GM2166 GM857 GM1520b GM1520a GM1886 GM1520c GM2218 GM2148 GM2283 GM1527 GM2531 GM1453 GM1408GM2348 GM1581 GM1172 GM1460 GM2104 GM1875 GM1933 GM1526GM117 GM1303 GM1322 GM2582 GM784 GM1563 GM2207 GM2084 GM2040 GM1341 GM2383 GM2320GM1243 GM1481 GM1868 GM2722 GM2303 GM1195 GM927 GM926 GM2058 GM2029 GM2140 GM1764 GM2041 GM1624 GM1163 GM1561 GM2316 GM1107 GM810 GM2577 GM1562 GM951GM2082 GM2266 GM1373 GM950 GM2001 0.0 2.4 6.0 9.3 18.9 19.4 24.3 29.2 31.9 33.0 34.1 35.7 36.2 36.7 37.0 37.3 38.9 41.4 42.6 47.5 52.1 58.4 59.0 61.7 65.5 75.4 2B GM1865 0.0 9.8 14.7 20.5 20.6 21.9 24.0 24.1 25.7 28.3 30.8 37.2 37.6 47.0 47.5 48.2 49.7 49.9 50.0 52.2 53.9 GM1930 GM1819 GM2016 GM733 GM2500 GM1160 GM1724 GM1852 GM2047 GM1946 GM2797 GM1714 GM2496 GM1386 GM1598 GM2491 GM1075 GM1503 GM1516 GM2455 GM2474 GM126 62.6 GM1668 GM2111 70.1 74.1 74.2 76.5 77.8 78.2 79.3 GM2257 GM2121 GM2814 GM1910 GM2098 GM1836 GM2808 87.8 88.2 92.3 96.7 96.8 97.5 99.0 103.7 GM2838 GM817 GM1655 GM1355 GM922 GM2232 GM2186 GM2845 GM1742 GM1520 GM2218 GM2217 GM1718 GM1076b GM1527 GM450GM472 GM1016GM279 GM114GM2023 GM1563 GM2819 GM1172GM1868 GM1303 GM2411 GM238 GM1832 GM1568 GM108 GM40 GM1137 GM927 GM1074 GM1163 GM439 GM471 GM2340 100.0 100.5 GM2762 GM2763 GM2266 107.1 GM2124 0.0 3.4 GM2007 GM1840 0.0 GM1817 8.6 GM1963 Figure 1 (See legend on next page.) 3A 0.0 1.6 GM1865 GM656 10.0 GM1819 26.0 28.2 GM2196 GM87GM1860 43.0 GM509 49.1 49.6 GM1714 GM1538GM2581 54.5 GM2580GM376 60.8 GM1386 71.7 79.7 81.7 82.4 83.4 84.5 86.8 89.2 91.6 92.1 93.2 97.6 98.7 102.5 GM77a GM1075 GM1516 GM1180 GM2655GM421 GM574 GM126 GM1598 GM430b GM2656 GM2272 GM1668 GM534 GM1910 GM1836 GM1821 GM266 82.9 4/9B.1 4/9B.2 GM2304 GM205 GM973 GM2828 Page 5 of 12 122.8 124.4 GM431 GM1051 132.2 GM2232 138.3 GM2845 3.9 6.6 9.5 14.8 26.0 29.1 32.6 34.7 35.5 35.6 39.7 42.9 43.3 44.3 45.9 48.3 55.4 57.2 57.5 57.8 57.9 58.0 58.4 58.6 58.9 59.3 59.8 62.1 62.9 64.4 64.7 65.6 66.7 67.4 67.7 68.0 68.7 69.4 70.2 71.2 71.7 72.0 72.4 74.9 75.9 77.0 81.0 81.5 82.6 83.2 90.2 91.1 94.5 95.3 96.8 102.0 102.9 106.3 112.0 112.9 115.8 GM32 GM2599 GM2598 GM2818 GM2261 GM2372 GM1760 GM1149 GM1609 GM1191 GM1425 GM2764 GM2087 GM1266 GM2407 GM1360 GM2693GM2694 GM1733 GM2230GM2524 GM2467 GM1656 GM1487 GM828 GM2206 GM2364 GM2352 GM2184 GM2274 GM774 GM1566 GM1034 GM898 GM1618 GM1473 GM1763 GM19 GM2008 GM1583 GM1500 GM1053GM2449 GM783 GM2586 GM2402 GM1645 GM1659a GM1681 GM1443 GM1369 GM1502 GM1717 GM2215 GM2556 GM1249 GM2772GM1726 GM2051 GM1883 GM2416 GM2027 GM743 GM2419 GM2528 GM1108GM1885 GM2069 GM866 GM2765 GM1084 GM2792a GM714 GM1326 GM1954 GM1321 GM1652 GM2228 GM2103 GM2805 GM1213 GM1591 GM1536 GM74 GM2302 GM2301 GM1263 GM1854 GM2757 0.0 8.9 9.1 9.4 12.1 13.4 14.0 15.7 17.3 20.2 20.4 21.2 30.1 37.9 38.0 38.3 39.1 39.9 40.8 42.3 46.3 46.7 47.7 49.5 49.6 51.2 51.7 52.1 54.0 54.6 54.9 57.2 58.6 59.1 59.7 60.5 61.0 61.8 62.6 63.0 64.4 65.0 67.6 69.4 75.5 77.4 77.9 78.3 78.5 78.6 79.1 81.6 85.0 85.7 86.2 95.0 95.9 97.0 101.1 102.4 102.7 103.3 105.1 108.4 110.0 110.4 114.5 119.8 121.7 122.3 122.9 124.6 124.7 124.8 125.2 127.1 127.7 130.5 131.2 138.4 139.9 145.6 4A 3B 0.0 2.7 9.4 9.9 12.6 13.7 15.9 26.2 34.6 36.2 36.7 50.0 53.2 54.8 56.9 58.5 61.7 66.0 68.7 69.2 69.7 70.8 71.9 72.4 72.9 74.0 75.6 78.0 81.6 85.4 86.9 88.1 88.7 93.1 96.9 98.5 100.1 103.3 104.4 104.9 105.4 105.9 106.8 108.6 110.8 112.9 117.2 117.8 4/9B 4/9B.3 GM1840 GM2014 GM2091 GM1120 GM2010 GM1528 GM76 GM1647 GM1466 GM2108 GM1445 GM2448 GM1738 GM839 GM1173 GM1867 GM1565GM2246 GM1021 GM1720 GM1755 GM1296 GM2589 GM218 GM2813 GM1887 GM1959 GM2311 GM2572 GM2006 GM1465 GM1995GM1070 GM1805 GM916 GM1186GM1643 GM1167GM96 GM2142 GM1013 GM2482 GM2480 GM1554 GM162 GM1190 GM1143 GM1907 GM1919 GM1679 GM1594 GM1298 GM1729 GM1223 GM2236 GM13 GM2583 GM942 GM955 GM1062 GM1817 GM735 GM1963 GM1045 GM2755 GM2021GM2020 83.9 85.0 88.3 92.1 93.2 97.6 98.1 100.8 105.2 GM2010 GM1918 GM426 GM1670 GM76 GM682 GM1466 GM839 GM1173 GM1984 GM2246 GM2778b GM2311 GM890 GM2542 GM2553 GM1823 GM1565 GM430a GM952 GM2847 GM1478 GM2832 GM1462 GM2690 GM660 GM707 GM1932 GM2479 GM2113 GM1651GM1744 GM2400 GM1965 GM1861 GM425GM1922 GM2689GM1194 GM2326GM1136 GM423GM70 GM2074 GM663 GM1403 GM2488 GM110b GM390GM1135 GM1167 GM2841 GM96 0.0 1.1 3.6 4.3 4.8 7.5 9.1 12.9 14.5 17.7 18.2 18.7 19.2 23.6 29.1 30.2 30.7 32.9 34.2 35.5 45.2 47.4 54.0 57.8 58.3 60.5 65.4 69.8 75.3 79.1 79.6 81.5 83.4 118.5 GM344 123.8 127.4 130.9 131.4 131.9 134.6 GM231 GM2778a GM2521 GM2438 GM1338 GM2120 141.8 143.4 143.9 144.4 147.1 148.7 152.2 158.0 159.7 GM792 GM1650 GM2026 GM1893 GM2793 GM2558b GM1906 GM66 GM2450 180.0 183.2 183.7 184.8 GM1907GM162 GM541 GM2181 GM493 192.0 195.2 GM1067 GM2106 199.8 GM942a 205.0 208.3 209.9 0.0 2.2 4.9 GM64 GM1298 GM622 GM1056 GM1045 GM2081 8.8 GM1199 20.3 GM2070 41.5 GM1459 47.1 GM1803 5A 4.0 6.0 9.5 12.4 12.7 13.7 16.8 18.0 20.6 23.8 24.2 36.3 38.3 39.5 40.8 44.2 46.6 47.0 47.6 48.7 49.8 50.7 51.0 51.5 52.9 53.1 53.2 53.4 53.5 53.7 53.8 54.4 54.8 54.9 55.0 57.1 58.7 60.4 61.3 63.8 64.7 65.9 66.2 69.1 69.4 69.5 69.7 70.5 71.1 71.3 71.5 73.2 76.7 77.4 84.4 84.8 91.0 91.1 91.7 112.0 112.1 116.4 GM32 GM2599 GM1149 GM1609 GM2372 GM1425 GM1003GM2543 GM2011 GM2355 GM2407 GM2321 GM1487 GM97GM11 GM1484 GM1566 GM1473 GM1551 GM1779bGM2088 GM415 GM1846 GM2224 GM1573 GM1361 GM469 GM49 GM1645 GM1447 GM121 GM1996 GM1717 GM1874 GM1545 GM736 GM616 GM2308 GM2688 GM2765 GM427 GM460 GM2757 GM1854 GM1642 GM2302 GM74 GM832 GM2060 GM2301 GM195 GM1321 GM1954 GM2801 GM1407 GM2730GM2729 GM655 GM866 GM211 GM877 GM2528 9A 5.3 7.4 21.7 23.7 24.7 27.0 28.9 33.3 34.4 36.6 42.0 42.3 48.3 48.9 52.3 52.6 53.2 54.5 55.1 55.5 55.6 55.7 55.9 56.6 56.7 57.3 59.9 60.2 62.4 83.0 89.2 89.3 91.1 93.0 94.1 94.2 99.4 100.5 5B 5B.1 GM2770 GM2703 GM1898 GM1728 GM1253 GM1519 GM948 GM1261 GM2793 GM1119 GM1118a GM1317 GM1154 GM1313 GM2771 GM2663 GM2662 GM1987 GM1332 GM2092 GM2031 GM2043 GM874 GM996 GM1049 GM2820 GM1892 GM2078 GM1257 GM68 GM1577 GM2160 GM1482 GM1955 GM1967 GM16 GM28 GM1018 GM2347 GM1890 GM2429 GM1218GM2487 GM2672 GM2673GM1782 GM2137 GM2231 GM2769 GM1788 GM1227 GM1228 GM1878 GM2017 GM1843 GM1778 GM1293 GM944 GM1902 GM1912 GM1816 GM1904 GM1702 GM1162 GM1944 GM1352 0.6 2.2 2.4 4.1 6.5 7.2 7.7 8.1 8.7 8.9 9.0 9.2 9.7 10.0 10.3 10.5 11.0 11.6 11.9 12.4 13.0 13.5 14.0 14.2 14.6 15.0 15.9 16.6 17.6 18.3 19.8 19.9 20.0 20.2 20.6 21.3 21.5 21.6 21.8 22.9 23.7 24.9 25.1 26.4 27.1 28.6 28.9 29.2 30.7 31.8 32.6 34.7 34.9 38.1 41.0 41.9 42.2 42.9 47.5 48.6 49.5 50.4 53.8 68.0 68.1 68.2 77.3 GM2270c 3.9 GM2770b 14.8 20.1 23.6 28.2 35.0 35.6 37.3 44.3 51.3 54.6 59.5 62.2 67.7 70.9 72.5 73.0 74.6 75.7 76.2 76.7 78.5 81.2 83.2 83.9 85.0 86.1 87.3 88.5 89.7 92.1 95.7 97.8 101.0 101.5 102.0 102.5 105.2 114.8 8A GM1174 GM1856GM1835 GM2438 GM1600GM324 GM2120GM1338 GM1237 GM1952GM1876 GM1559 GM1650 GM1732 GM1893 GM1796 GM66 GM2164 GM1069 GM2172 GM2839GM2359 GM1911 GM1979GM2792b GM1834 GM2778 GM565 GM328 GM2847 GM2553 GM2292 GM1851 GM1411GM2003 GM2389GM2843 GM1291 GM1841 GM7GM1998 GM1999GM1047 GM2033 GM1803 GM2529 GM1459 GM1117 GM1329 GM1312 GM1607 GM1199 GM2081 GM1389 0.0 GM438 GM1822 GM340 GM2427 GM947b GM947a GM948 GM1892 GM2092 GM337 GM1989 GM1987 GM1988 GM2483 GM151 GM2771 GM1313 GM1317 GM2505 GM2298 GM1118 GM654GM504 GM1739 GM1967 GM2078 GM1423 GM68 GM1680 GM1511 GM2160 GM1577 GM2031 GM2558a GM611 GM1908 GM1555 GM261 GM28 GM816 GM2770a GM1018 GM1297 GM2673GM1782 GM1843 GM2769GM2137 GM1284 GM1890 6A 0.0 GM2057 GM1521 GM1495 GM1682 GM1940 GM226 GM1567 GM1548 GM1547 GM2170 GM1286 GM1385 GM1968 GM2844 GM2063 GM664GM959 GM1505 GM2701 GM1185GM92 GM2702 GM988 GM1461 GM1035GM1096 GM1962GM1896 GM83 GM2366 GM2306 GM1909 GM1617 GM1748 GM900 GM2425 GM1572 GM2817 GM255 GM847 GM1498 GM2446 GM2109 GM2110 GM2414 GM2337 GM2767 GM2066 GM1490 GM1497 GM1506 7.2 13.3 13.8 14.2 18.0 24.5 25.4 32.8 34.1 36.1 37.1 42.4 44.8 46.2 51.7 54.5 54.9 55.9 56.1 57.1 58.2 58.4 59.1 59.3 60.1 61.4 62.3 63.6 66.4 67.0 68.4 70.1 71.1 71.7 73.5 74.3 77.2 80.7 83.2 89.6 93.6 94.2 99.1 99.3 100.4 105.3 0.0 0.6 GM2557 GM175 13.3 16.8 GM1457 GM1931 32.2 GM2779 44.0 44.6 46.2 47.8 48.3 GM987 GM2062 GM2072 GM226 GM1567 57.8 GM1105 67.3 70.6 72.8 73.9 77.7 GM1187 GM1838 GM2170 GM612 GM1385 GM935GM1756 GM1968 GM45 80.4 82.4 102.9 105.1 106.2 108.4 110.0 GM452 GM1185 GM2384 GM92 GM268GM3 GM2337 GM2414 GM2110 GM2456 GM467 93.6 99.1 99.6 120.9 GM752 GM1662 127.6 130.8 131.9 132.4 134.0 135.6 GM1498 GM2817 GM1572 GM2392 GM847 GM1479 GM544 22.5 GM2381 143.4 144.5 147.2 GM1748 GM1857 GM2824 30.1 GM1546 161.6 164.2 GM1499 GM72 0.0 3.4 GM1616 GM1702 7.5 GM1944 12.2 7B GM2099 GM1587 GM1957 GM2417 GM1238 GM1713 GM1659b GM71 GM2713GM2712 GM1797 GM2564 GM2827 GM1509 GM1189 GM1917 GM2664GM2665 GM2176 GM1831 GM1936 GM2601 GM1839 GM2600 GM2312 GM2339 GM1934 GM1905 GM1901 GM1629 GM1240 GM1903a GM2640 GM2644 GM1798 GM1001 GM2643 GM2832 GM1201 GM1709 GM2788 GM1613 GM2842 GM2551 GM2144 GM1281 GM2089 GM2787 GM2125 GM1092 GM2182 GM741 GM1165 GM1965 GM58 GM1136 GM2101 GM1744 GM2400 GM1844 GM883 GM1961 GM2758 GM10 GM1932 GM2055 GM1872 GM1575 GM1320 GM1628 GM1134 GM2269 GM1073 GM1239 GM2421 6B 8B 8B.1 GM2503 8.1 11.4 15.2 17.4 19.6 20.7 GM2339 GM1936 GM1477GM1937 GM1315 GM2118 GM1853 GM69 26.5 GM156 32.3 33.9 36.6 GM1347 GM2343 GM1214 0.0 2.2 GM1779a GM2454 12.2 15.0 GM2177 GM1929 19.6 20.4 24.3 24.8 28.1 GM2791 GM2067 GM1899 GM1302 GM477 37.0 40.4 43.6 GM1140 GM1175 GM1410 61.6 64.8 67.2 69.4 69.9 71.6 75.7 76.9 78.5 79.6 81.8 82.9 83.5 87.8 91.3 92.2 92.7 93.2 95.9 97.5 99.1 99.6 100.1 101.7 103.3 104.9 107.6 108.1 109.2 114.1 117.9 119.5 120.6 122.7 123.2 123.7 125.9 132.5 135.2 136.8 147.5 GM704 GM624 GM2788 GM2785 GM1427 GM1623 GM1880 GM708 GM920 GM2605 GM1076a GM2034 GM2551 GM437 GM1151 GM1165 GM2842GM1844 GM59 GM90 GM30 GM2089 GM2746 GM2834GM248 GM2826 GM1587 GM1957 GM871 GM2751 GM1638GM2289 GM2750 GM71 GM1509 GM1797 GM2099 GM2176 GM1917 GM2664 GM2665 GM691 GM1831 GM1469 GM1842 181.1 184.0 185.1 GM339 GM1905 GM2534 0.0 4.4 6.0 7.1 GM462 GM1239GM2269 GM945 GM1073 7A 0.9 3.1 3.4 4.0 4.6 4.9 5.0 7.3 8.8 9.5 11.5 12.3 12.6 13.6 14.4 15.4 15.5 15.6 16.7 16.8 17.8 18.6 20.7 20.9 21.2 21.9 22.0 22.6 24.7 26.7 28.1 28.7 29.4 30.9 31.1 32.0 32.1 32.2 34.6 36.9 38.4 46.5 48.9 55.6 62.3 64.3 71.3 77.2 78.4 78.5 79.6 80.6 GM2473 GM852 GM1633 GM2073 GM963 GM2146 GM2147 GM1621 GM2177 GM1929 GM1250 GM1175 GM1140 GM2454 GM1785 GM2050 GM2156 GM2199 GM1942 GM1494 GM1632 GM1111 GM1114 GM846 GM1688 GM2588 GM1023 GM1623 GM2222 GM1858 GM1076 GM1451 GM2034 GM2423GM1651 GM2326 GM1922 GM1937 GM1315 GM1829 GM1477 GM59 GM1219GM2747 GM2494 GM1701 GM802 GM1853 GM69 GM1214 GM980 GM1347 GM1348GM2526 GM840 GM953 Guo et al. BMC Genomics 2012, 13:608 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/13/608 Page 6 of 12 (See figure on previous page.) Figure 1 The alignment of A- and B- genome linkage maps of Arachis. Alignment of B- genome linkage groups with A- genome linkage groups, orthologous markers are highlighted in bold. The B- genome map was based on EST-SSR markers and genomic SSR markers, and was obtained through the analysis of 94 F2 plants from the intraspecific crossing of A. batizocoi. The A- genome map was based on EST-SSR markers and genomic SSR markers, obtained through the analysis of 94 F2 plants from the intraspecific crossing of A. duranensis. The dotted lines indicate the correspondences between loci. constructed in a B-genome diploid peanut, and also represents the first intraspecific map of a B-genome species. Significant segregation distortion (α ≤ 0.05) was observed for 18 (4.0%) marker loci, distributed in seven linkage groups representing six B-genome chromosomes (Additional file 8), which was much lower than previously reported segregation distortion (21.5%) in an interspecific B-genome linkage map [24]. Similarly, high levels of skewed segregation in interspecific crosses compared to intraspecific crosses have been reported in both barley and cowpea [64,65]. In the A. batizocoi map, a total of 11 markers skewed towards parental line 9484 and two towards 30081. Linkage group 1B contained the largest number of distorted marker loci (10 marker loci comprising 55.6% of the total distorted markers). All the marker loci on this linkage group skewed towards 9484 and clustered within a 37.1 cM genomic region, which is 37.8% of the total mapping distance for 1B and 26.3% of the marker loci for this chromosome. Linkage groups 3B, 5B, and 8B had no markers showing segregation distortion (Additional file 8). Synteny between A-genome and B-genome linkage maps The B-genome linkage groups were aligned to A-genome linkage groups by 167 putative orthologous marker loci, 10 to 25 in each chromosome (Table 3). Compared to previous reports, which identified 51 shared markers between the A- and B-genome maps [24], or 53 SSR markers that mapped on both A and B subgenomes in the tetraploid map [30], our comparisons are based on a higher density, higher information content map, and should more precisely position chromosomal rearrangement events within defined genomic regions. Syntenic segments were supported by multiple markers in the same linear order with some incongruities reflecting simple translocations and inversions. A high degree of macrosynteny was observed when comparing the nine major linkage groups identified in the B genome to the 10 major linkage groups (1A-10A) in the A genome (Figure 1). Linkage groups 5B and 5B.1 can both be aligned with linkage group 5A, with putative orthologous markers showing colinearity. Similarly, LGs 8B and 8B.1 can both be aligned with linkage group 8A. Since the subgroups couldn’t be merged into one linkage group with a minimum LOD threshold of 3.0 without a >50 cM gap between the adjacent subgroup loci, the two subgroups were displayed separately. Completely syntenic chromosomes For LGs 2A and 2B, all 13 putative orthologous markers were colinear, covering a map distance of 138.3 cM (100%) on B2 and 103.7 cM (100%) on A2. Therefore, 2B and 2A showed a high degree of macrosynteny as previously reported [24], although we did not detect any split correspondence relationship with A2 and B10 as in the previous report [24]. Ten putative orthologous markers between 10A and 10B indicated well defined macrosynteny. The common markers spanned 81.1 cM on 10B and 75.0 cM on 10A, accounting for 75.7% and 68.0% of the total linkage group length, respectively. Chromosomes with inversions The 12 putative orthologous markers between 1A and 1B were clustered into two chromosome segments. One segment was colinear, containing 10 putative orthologous markers with 28.2 cM map coverage on 1B and 34.5 cM on 1A, accounting for 28.7% and 37.7% of the total lengths, respectively. The other chromosome fragment had a reversed colinear order, with two putative orthologous markers spanning 58.5 cM on 1B and 40.7 cM on 1A, accounting for 59.6% and 44.5% of the total lengths, respectively. The reversed region defined by two putative orthologous markers on both 1A and 1B indicated a likely inversion between these two chromosomes. This observation was similar to previous reports [24,30]. For LGs 3B and 3A, 22 common markers were clustered into two chromosomal segments. The first of these was extensively colinear between 3A and 3B, with 12 putative orthologous markers spanning 88.7 cM (75.3%) on 3B and 74.9 cM (51.4%) on 3A. The other fragment had a reversed order with 10 putative orthologous markers spanning 20.9 cM (17.7%) on 3B and 43.2 cM (29.7%) on 3A. The chromosome segment inversion between 3A and 3B has not been previously reported. For LGs 5A and 5B, there were 25 putative orthologous markers in total, spanning the entire 5B, 4.1 cM (13.6%) of 5B.1, and 108.0 cM (92.8%) of 5A, with a generally colinear order, except for a chromosome segment with nine putative orthologous marker loci spanning 31.4 cM (27.4%) in 5B, and 49.0 cM (42.1%) in the reversed order for 5A. Since the inverted chromosome segments accounted for nearly 30% of the total linkage groups’ lengths and 36.0% (9 out of 25) of the total putative orthologous markers in both A and B genomes, Guo et al. BMC Genomics 2012, 13:608 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/13/608 there could be an inverted chromosome segment between 5A and 5B, which also has not been detected from previous reports. Between chromosomes 6A and 6B, there were 15 putative orthologous markers that spanned 95.6 cM in 6B and 69.1 cM in 6A, accounting for 58.2% and 65.6% of the total lengths on the linkage groups, respectively. Seven putative orthologous markers were mapped in a colinear manner at the top part of both linkage groups. Segments containing eight putative orthologous markers at the bottom part were involved in an inversion event. The inverted chromosome segment on 6B was 40.5 cM long and accounted for 24.7% of the entire 6B. The corresponding segment on 6A was 23.2 cM, accounting for 22.0% of the entire 6A. This inversion was reported previously [24], but they also reported the split correspondence relationships between B6 and A10, which was not revealed in our study. Complex chromosome rearrangements In addition to the observed simple inversion events, we also found more complex chromosome rearrangements. This intraspecific A. batizocoi genetic map has nine major linkage groups instead of the expected 10. When the A- and B-genome linkage groups were aligned, one of the major B-genome linkage groups was found to correspond to both 4A and 9A and was therefore named as 4/9B. Another smaller linkage group also had putative orthologous markers with 4A and 9A therefore it was named 4/9B.3. The linkage group 4/9B contains 80 markers spanning 209.9 cM, while 4/9B.3 contains 7 markers spanning 47.1 cM. In addition, there were two smaller LGs, 4/9B.1 and 4/9B.2, containing two markers each with genetic distances of 3.4 cM and 8.6 cM, respectively. They were also designated as fragments of 4/9B according to their putative orthologous markers with 4A and/or 9A. There were several reasons that we did not further separate 4/9B into 4B and 9B. Firstly, these linkage groups remained inseparable even when increasing the LOD threshold to 20. Secondly, the markers were located densely and evenly, with no obvious gaps between two chromosome fragments. The average marker density was 2.7 cM/locus on 4/9B and 7.9 cM on 4/9B.3, which was comparable with the rest of the genome. Thirdly, the effects on map order due to distorted segregation were minimal. There was only one marker that was distorted on each of 4/9B and 4/9B.3. Double crossover events were evaluated alongside 4/9B and 4/9B.3 but no unusual segregating markers or marker blocks were observed. Fourthly, when aligning 4/9B, 4/9B.1, 4/9B.2 and 4/9B.3 with 4A and 9A separately, by using only putative orthologous markers, 4A with 4/9B, 4/9B.1, 4/9B.2 and 4/9B.3 showed complete colinearity, while 9A and 4/9B, 4/9B.1, 4/9B.2 and 4/9B.3 showed a possible Page 7 of 12 inversion. Synteny between 4A and 4B had been reported by Moretzsohn et al. [24] and Fonceka et al. [30]. An inversion between 9A and 9B was also consistent with a previous report [30]. Lastly, all putative orthologous markers between 4A and 9A were interspersed alongside 4/9B, 4/9B.1, 4/9B.2 and 4/9B.3. From a previous cytological study of the intraspecific variability of A. batizocoi using five accessions [66], hybrids between accessions 30081 and 9484 had reduced pollen stainability (88.6%). Moreover, cytogenetic analyses of F1s from the same cross showed a low frequency of quadrivalents [11,66], indicating a reciprocal translocation that would cause pairing between two non-homologous chromosomes during meiosis. The similarity between the two chromosomes involved in reciprocal translocation could explain the integrated linkage group 4/9B in our study. A quadrivalent relationship was observed when aligning 7B and 8B with 7A and 8A. On linkage group 7B, there were two colinearly located putative orthologous markers with 7A, covering 3.3 cM and accounting for 9.0% of the total length on 7B. The bottom segment had seven colinearly located putative orthologous markers with 8A, spanning 21.4 cM, about 58.5% of the entire 7B. On 8B, a colinear fragment with 7A was located from 2.2 cM (from the top) to 91.2 cM (from the top), with nine putative orthologous markers spanning a genetic distance of 89.0 cM (48.1% of 8B), whereas the other 18 putative orthologous markers with 8A were colinearly located from 67.2 cM to 184.0 cM (also from the top of the linkage group), spanning a genetic distance of 116.8 cM (63.1% of 8B). Moreover, three colinear putative orthologous markers with 8A also were found on 8B.1. This may indicate a reciprocal translocation between 7B and 8B. Similar translocations on corresponding linkage groups were found both at the diploid level [24] and tetraploid level (from the crosses of a tetraploid variety with a tetraploid AABB amphidiploid) [30]. However, the previous reports did not identify the correspondence between LGs a07 (corresponding to LG 7A in our study) and b08 (corresponding to LG 8B in our study), which might due to their relatively shorter chromosome coverage on LG 8B (29.8 cM in the synthetic amphidiploid map and 86.4 cM in the diploid map versus 192.2 cM in this report) [24,30]. Therefore, the rearrangement is most likely a reciprocal translocation, and may have contributed to the divergence of A and B genomes, perhaps as an ancient event that occurred before peanut polyploidization and remained subsequent to tetraploidization of cultivated peanut [30]. Although the chromosomes of A. hypogaea have differentiated botanical varieties and individual lines that can be separated based on location of the secondary constriction and symmetry of chromosomes [67], Guo et al. BMC Genomics 2012, 13:608 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/13/608 Page 8 of 12 Table 3 Number of common markers between the corresponding linkage groups from A- and B-genome genetic maps Linkage group No. of marker loci 1B 38 2B 35 3B 62 4/9B* 91 5B** 58 6B 44 Linkage group 1A 2A 3A 4A 5A 6A 7A 8A 9A 10A Total No. of marker loci 73 40 89 67 66 51 56 75 55 61 633 12 13 22 18 13 25 15 7B 13 7 2 8B*** 65 9 21 10B 39 Total 445 10 167 *4/9B including 4/9B, 4/9B.1, 4/9B.2, and 4/9B.3. **5B including 5B and 5B.1. ***8B including 8B and 8B.1. introgression of disease and insect resistance traits from wild species into the cultivated peanut has been successful [68]. Comparative mapping summary Comparison of the genetic linkage maps of A and B genomes indicated that the chromosomal differences between these two species could be explained by a total of five inversions and one reciprocal translocation under our current mapping resolution. Because of the possible minor differences in ordering of tightly linked markers, confident identification of small inversions is more difficult than translocations. To detect the confidence of inversion, we compared our predicted inversions with previously published maps. Moretzsohn et al. [24], used different A- and B-genome diploid species and showed four inversions and one translocation by comparing diploid A- and B-genome maps from interspecific mapping populations. Fonceka et al. [30] used a synthetic allotetraploid population to compare linkage maps of the A and B subgenomes, which revealed at least three inversions, while Burow et al. [29] revealed four inversions. Our study identified additional translocation events by using intraspecific diploid mapping populations, and also detected a reciprocal translocation within the B-genome species A. batizocoi. Chromosomal rearrangements are common within and among A- and B-genome diploid species. For example, in an analysis to determine the intraspecific variability within the B-genome species A. batizocoi [66], quadrivalents, hexavalents and octavalents were observed during meiosis in F1 hybrids of different accessions, indicating one to three reciprocal translocations that differentiate these accessions. Thus, karyotypic evolution via translocations was considered to be an important mechanism for species differentiation [66]. In our study, the linkage map from A. duranensis was used as the reference map from which the chromosome rearrangements between A and B genomes were inferred [63]. However, chromosomal rearrangements within the Agenome could exist when considering the higher genetic diversity among the various accessions of the A-genome species, A. duranensis. Previous research found a low frequency (0.01-0.26/PMC) of multivalents in 12 of 27 hybrids from crosses of A. duranensis accessions [69], and quadrivalents were identified in all these 12 hybrids, which likely represents chromosome translocations within this species. The asymmetrical chromosomes found in different accessions, furthermore, indicated the presence of translocations. In addition, varied fertility of F1s (from less than 4.7% to greater than 95%) and the diverse morphological traits also indicated wide genetic diversity in A. duranensis [12,69]. Univalents, laggards, and multivalents can all be detected in intraspecific Agenome and interspecific A- by B-genome F1 hybrids, indicating the prevalence of chromosomal rearrangements in peanut diploid species. We herein verify by genetic mapping that a chromosomal translocation has occurred within the B-genome species A. batizocoi. Our findings of one reciprocal translocation between chromosomes 7 and 8 in A-genome species A. duranensis and B-genome species A. batizocoi is consistent with previous reports [24,30]. The slight discrepancy of the number of inversions between A- and B-genome chromosomes could be due to the genetic variation of the different accessions/species used in the mapping population development. Guo et al. BMC Genomics 2012, 13:608 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/13/608 Conclusions The present study developed and characterized an extensive set of EST-SSR and genomic SSR markers. Comparative mapping of our intraspecific A- and B-genome populations showed a high degree of macrosynteny between A- and B-genome diploid species of peanut. Consistent with previous cytological studies, it was evident that chromosomal rearrangements were common within and between both A- and B-genome diploid species. Karyotypic evolution via translocations could be an important mechanism for differentiation of the species. Our findings will facilitate an understanding of tetraploid peanut genome origin and eventually promote its genetic improvement. Page 9 of 12 www.gramene.org/db/markers/ssrtool) and for imperfect motifs using FastPCR (http://primerdigital.com/fastpcr. html). The repeat count (n) threshold for each motif type was set for n ≥ 5. Information on repeat motif, repeat number, and SSR start and end positions within the respective ESTs were extracted from the SSR-IT output. The grouping of SSR motifs into respective repeat classes was performed following the method of Jurka and Pethiyagoda [70]. Flanking forward and reverse primers were designed using Primer3 (http://frodo.wi.mit. edu) [71]. The parameters were set as follows: primer length from 19 to 23 with 21 nucleotides as optimum; amplification size of 100 to 400 base pairs; annealing temperatures from 59°C to 63°C with a maximum difference of 3°C; and GC contents from 25% to 45%. Methods Plant materials Mapping population An F2 population consisting of 94 plants was developed by selfing four F1 plants from the intraspecific cross of two A. batizocoi lines PI 298639 (accession no. K 9484) and PI 468327 (accession no. GKBSPSc 30081). The Agenome F2 mapping population also consisted of 94 plants from the intraspecific cross of A. duranensis PI 475887 and Grif 15036 [63]. Plant materials for EST-SSR characterization Eight genotypes including four tetraploid and four diploid accessions were used to screen all 2,138 markers. The four tetraploid genotypes in the screening panel included Tifrunner (A. hypogaea subsp. hypogaea var. hypogaea), a runner-type peanut cultivar; GT-C20 (A. hypogaea subsp. fastigiata var. vulgaris), a Spanish exotic accession with reduced aflatoxin contamination; NC94022 (A. hypogaea subsp. hypogaea), an exotic accession with higher resistance to TSWV (tomato spotted-wilt virus) derived from var. hirsuta; and SunOleic 97R (A. hypogaea subsp. hypogaea var. hypogaea), a high oleic runner-type cultivar. For the diploid genotypes, PI 475887 and Grif 15036 are Agenome germplasm accessions of A. duranensis, while accessions 9484 and 30081 are B-genome germplasm accessions in A. batizocoi. They are parental lines of the respective A- and B-genome mapping populations. SSR discovery, marker development, and length polymorphism screening Mining the peanut EST database for SSRs The sequence database used for SSR marker development harbors a total of 70,771 long-read (Sanger) ESTs and 270,957 short-read (454) ESTs assembled into 101,132 unigenes (Accession: PRJNA49471; Additional file 1). Unigenes in the transcript assembly were screened for perfect repeat motifs using SSR-IT (http:// Mining genome survey sequences (GSSs) for SSRs Methylation filtered (ME) and unfiltered (U) genome libraries were constructed from A. duranensis, A. batizocoi, and A. hypogaea by Orion Genomics (Saint Louis, Missouri) [72]. A total of 9,517 unique genome survey sequences (GSS) were used for mining SSRs. Similarly, SSR-IT was used to screen for perfect repeat motifs (http://www.gramene.org/db/markers/ssrtool [47]), and Primer3 (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu) [71] was used for primer design. Primers were screened for overall amplification quality against 12 genotypes, including four diploid and eight tetraploid accessions (Additional file 6), and with SSCP gels by silver staining according to protocols described previously [73]. SSR marker genotyping Genomic DNA was isolated from young leaves by a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method [74]. SSR markers were genotyped on an ABI3730XL Capillary DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using forward primers labeled with FAM, HEX, or TAMRA fluorophores. PCR was performed in a 12 μL reaction mixture containing 1.0× PCR buffer, 2.5 mM Mg++, 0.2 mM each of dNTPs, 5.0 pmol of each primer, 0.5 unit of Taq polymerase, and 10 ng of genomic DNA. Touchdown PCR was used to reduce spurious amplification [75]. The SSR markers were screened for amplification and length polymorphisms using GeneMapper 3.0 software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Genetic mapping, macrosynteny analysis, and cMap database construction A total of 481 polymorphic markers were used to screen 94 F2 progenies for map construction. Segregation distortion at each marker locus was tested against the expected segregation ratios (1:2:1 for codominant markers and 3:1 for dominant markers) using a chi-square Guo et al. BMC Genomics 2012, 13:608 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/13/608 goodness of fit test. Genetic maps were constructed using Mapmaker 3.0, with error detection on [76,77]. The initial linkage groups were first determined using the “group” application with a minimum likelihood odds (LOD) threshold of 15 and a maximum recombination fraction (θ) of 0.35. After aligning the draft map with the A-genome map [63], the LOD score was relaxed to 5 with θ =0.35 for a second analysis to merge the linkage groups that could align with the homoeologous Agenome linkage groups. Map distances (cM) were calculated using the Kosambi mapping function [78]. The “try”, “compare”, and “ripple” commands were used to confirm the marker order. Mapchart 2.2 was used for the graphic visualization of the linkage groups [79]. The A. batizocoi (B-genome) linkage groups were numbered based on colinearity to A. duranensis (Agenome) linkage groups except with the suffix “B”. The colinear subgroups in A. batizocoi were named by identical numbers with numerical suffixes, while an unseparated linkage group was identified by using linkage group numbers from the fused groups. Additional files Additional file 1: Summary of EST database for SSR discovery. Additional file 2: List of peanut EST-SSRs. Additional file 3: Overview of EST-SSR amplification. Additional file 4: Summary of marker polymorphism among peanut genotypes. Additional file 5: Effect of SSR length on frequency of polymorphism among tetraploid and diploid genotypes. Additional file 6: Arachis germplasm screened for genomic SSR markers developed from GSS sequences. Additional file 7: Peanut genomic SSR primer pair sequences used in this study. Additional file 8: The distribution of distorted loci along linkage groups for the B- genome map. Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Authors’ contributions YG led the experiments and drafted the manuscript. SK, ST, JEB, AFH, NK, EDN, DZ, CAT, and HTS participated in the experiments. POA and SJK designed experiments, coordinated the study, POA finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Acknowledgements This research was supported by funding from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture National Research Initiative Competitive Grants Program (#2006-35604-17242) awarded to SJK and POA and by the National Peanut Board, the Peanut Foundation, the Georgia Seed Development Commission, and Georgia Research Alliance endowment funding awarded to SJK. Author details 1 Institute of Plant Breeding, Genetics, and Genomics, 111 Riverbend Road, The University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA. 2Department of Horticulture, The University of Georgia, Tifton, GA 31973, USA. 3Department of Crop Science, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695, USA. Page 10 of 12 Received: 11 September 2012 Accepted: 31 October 2012 Published: 10 November 2012 References 1. Smartt J, Gregory WC: Interspecific cross-compatibility between the cultivated peanut and Arachis hypogaea L. and its behavior in backcrosses. Oleάgineux 1967, 22:455–459. 2. Kochert G, Stalker H, Gimenes M, Galgaro M, Lopes C, Moore K: RFLP and cytogenetic evidence on the origin and evolution of allotetraploid domesticated peanut, Arachis hypogaea (Leguminosae). Am J Bot 1996, 83(10):1282–1291. 3. Singh AH, Simpson CE: Biosystematics and genetic resources, Chap. 4. In The Groundnut Crop: A Scientific Basis for Improvement. Edited by Smartt J. London: Chapman & Hall; 1994. 4. Bertioli DJ, Seijo G, Freitas FO, Valls JFM, Leal-Bertioli SCM, Moretzsohn MC: An overview of peanut and its wild relatives. Plant Genetic Resources 2011, 9(1):134–149. 5. Seijo J, Lavia G, Fernandez A, Krapovickas A, Ducasse D, Moscone E: Physical mapping of the 5S and 18S–25S rRNA genes by FISH as evidence that Arachis duranensis and A. ipaensis are the wild diploid progenitors of A. hypogaea (Leguminosae). Am J Bot 2004, 91:1294–1303. 6. Smartt J, Gregory WC, Gregory MP: The genomes of Arachis hypogaea 1. Cytogenetics studies of putative genome donors. Euphytica 1978, 27:665–675. 7. Robledo G, Seijo G: Species relationships among the wild B genome of Arachis species (section Arachis) based on FISH mapping of rDNA loci and heterochromatin detection: a new proposal for genome arrangement. Theor Appl Genet 2010, 121:1033–1046. 8. Seijo G, Lavia GI, Fernandez A, Krapovickas A, Ducasse DA, Bertioli DJ, Moscone EA: Genomic relationships between the cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea, Leguminosae) and its close relatives revealed by double GISH. Am J Bot 2007, 94(12):1963–1971. 9. Halward TM, Stalker HT, Larue EA, Kochert G: Genetic variation detectable with molecular markers among unadapted germplasm resources of cultivated peanut and related wild species. Genome 1991, 34(6):1013–1020. 10. Ramos M, Fleming G, Chu Y, Akiyama Y, Gallo M, Ozias-Akins P: Chromosomal and phylogenetic context for conglutin genes in Arachis based on genomic sequence. Mol Genet Genomics 2006, 275(6):578–592. 11. Stalker HT, Dhesi JS, Parry DC, Hahn JH: Cytological and interfertility relationships of Arachis section Arachis. Am J Bot 1991, 78(2):238–246. 12. Stalker HT: A new species in section Arachis of peanuts with a D genome. Am J Bot 1991, 78(5):630–637. 13. Pandey MK, Monyo E, Ozias-Akins P, Liang X, Guimarães P, Nigam SN, Upadhyaya HD, Janila P, Zhang X, Guo B, et al: Advances in Arachis genomics for peanut improvement. Biotechnol Adv 2012, 30(3):639–651. 14. Temsch EM, Greilhuber J: Genome size variation in Arachis hypogaea and A. monticola re-evaluated. Genome 2000, 43(3):449–451. 15. Koilkonda P, Sato S, Tabata S, Kenta S, Hirakawa H, Sakai H, Sasamoto S, Watanabe A, Wada T, Kishida Y, et al: Large-scale development of expressed sequence tag-derived simple sequence repeat markers and diversity analysis in Arachis spp. Mol Breed 2012, 30(1):125–138. 16. Sujay V, Gowda MVC, Pandey MK, Bhat RS, Khedikar YP, Nadaf HL, Gautami B, Sarvamangala C, Lingaraju S, Radhakrishan T, et al: Quantitative trait locus analysis and construction of consensus genetic map for foliar disease resistance based on two recombinant inbred line populations in cultivated groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Mol Breed 2012, 30(2):773–788. 17. Sarvamangala C, Gowda MVC, Varshney RK: Identification of quantitative trait loci for protein content, oil content and oil quality for groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Field Crops Res 2011, 122(1):49–59. 18. Moretzsohn M, Hopkins M, Mitchell S, Kresovich S, Valls J, Ferreira M: Genetic diversity of peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) and its wild relatives based on the analysis of hypervariable regions of the genome. BMC Plant Biol 2004, 4:11–11. 19. Simpson CE: Use of wild Arachis species/introgression of genes into A. hypogaea L. Peanut Sci 2001, 28(2):114–116. 20. Abdou Y, Gregory W, Cooper W: Sources and nature of resistance to Cercospora arachidicola Hori and Cercosporodium personatum (Beck & Curtis) Deighton in Arachis species. Peanut Sci 1974, 1:6–11. Guo et al. BMC Genomics 2012, 13:608 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/13/608 21. Herbert TT, Stalker HT: Resistance to peanut stunt virus in cultivated and wild Arachis species. Peanut Sci 1981, 8:45–47. 22. Pande S, Narayana Rao J: Resistance of wild Arachis species to late leaf spot and rust in greenhouse trials. Plant Dis 2001, 85:851–855. 23. Subrahmanyam P, Moss J, Rao V: Resistance to peanut rust in wild Arachis species. Plant Dis 1983, 67:209–212. 24. Moretzsohn M, Barbosa A, Alves-Freitas D, Teixeira C, Leal-Bertioli S, Guimaraes P, Pereira R, Lopes C, Cavallari M, Valls J, et al: A linkage map for the B-genome of Arachis (Fabaceae) and its synteny to the A-genome. BMC Plant Biol 2009, 9(1):40. 25. Moretzsohn M, Leoi L, Proite K, Guimaraes P, Leal-Bertioli S, Gimenes M, Martins W, Valls J, Grattapaglia D, Bertioli D: A microsatellite-based, gene-rich linkage map for the AA genome of Arachis (Fabaceae). Theor Appl Genet 2005, 111:1060–1071. 26. Halward T, Stalker HT, Kochert G: Development of an RFLP linkage map in diploid peanut species. Theor Appl Genet 1993, 87(3):379–384. 27. Garcia GM, Stalker HT, Schroeder E, Lyerly JH, Kochert G: A RAPD-based linkage map of peanut based on a backcross population between the two diploid species Arachis stenosperma and A. cardenasii. Peanut Sci 2005, 32(1):1–8. 28. Leal-Bertioli S, Jose AC, Alves-Freitas D, Moretzsohn M, Guimaraes P, Nielen S, Vidigal B, Pereira R, Pike J, Favero A, et al: Identification of candidate genome regions controlling disease resistance in Arachis. BMC Plant Biol 2009, 9(1):112. 29. Burow M, Simpson C, Starr J, Paterson A: Transmission genetics of chromatin from a synthetic amphidiploid to cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.): Broadening the gene pool of a monophyletic polyploid species. Genetics 2001, 2:823–837. 30. Fonceka D, Hodo-Abalo T, Rivallan R, Faye I, Sall M, Ndoye O, Favero A, Bertioli D, Glaszmann JC, Courtois B, et al: Genetic mapping of wild introgressions into cultivated peanut: a way toward enlarging the genetic basis of a recent allotetraploid. BMC Plant Biol 2009, 9(1):103. 31. Lai Z, Nakazato T, Salmaso M, Burke JM, Tang S, Knapp SJ, Rieseberg LH: Extensive chromosomal repatterning and the evolution of sterility barriers in hybrid sunflower species. Genetics 2005, 171(1):291–303. 32. Strasburg JL, Scotti-Saintagne C, Scotti I, Lai Z, Rieseberg LH: Genomic patterns of adaptive divergence between chromosomally differentiated sunflower species. Mol Biol Evol 2009, 26(6):1341–1355. 33. Rieseberg LH, Willis JH: Plant speciation. Science 2007, 317(5840):910–914. 34. Rieseberg LH: Chromosomal rearrangements and speciation. Trends Ecol Evol 2001, 16(7):351–358. 35. Noor MAF, Grams KL, Bertucci LA, Reiland J: Chromosomal inversions and the reproductive isolation of species. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 2001, 98(21):12084–12088. 36. Liang X, Chen X, Hong Y, Liu H, Zhou G, Li S, Guo B: Utility of EST-derived SSR in cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) and Arachis wild species. BMC Plant Biol 2009, 9(1):35. 37. Song GQ, Li MJ, Xiao H, Wang XJ, Tang RH, Xia H, Zhao CZ, Bi YP: EST sequencing and SSR marker development from cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Electron J Biotechnol 2010, 13(3):1–9. 38. Proite K, Leal-Bertioli S, Bertioli D, Moretzsohn M, da Silva F, Martins N, Guimaraes P: ESTs from a wild Arachis species for gene discovery and marker development. BMC Plant Biol 2007, 7(1):7. 39. Cardle L, Ramsay L, Milbourne D, Macaulay M, Marshall D, Waugh R: Computational and experimental characterization of physically clustered simple sequence repeats in plants. Genetics 2000, 156(2):847–854. 40. Thiel T, Michalek W, Varshney R, Graner A: Exploiting EST databases for the development and characterization of gene-derived SSR-markers in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Theor Appl Genet 2003, 106(3):411–422. 41. Varshney R, Thiel T, Stein N, Langridge P, Graner A: In silico analysis on frequency and distribution of microsatellites in ESTs of some cereal species. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2002, 7(2A):537–546. 42. Portis E, Nagy I, Sasvári Z, Stágel A, Barchi L, Lanteri S: The design of Capsicum spp. SSR assays via analysis of in silico DNA sequence, and their potential utility for genetic mapping. Plant Sci 2007, 172(3):640–648. 43. Varshney RK, Graner A, Sorrells ME: Genic microsatellite markers in plants: Features and applications. Trends Biotechnol 2005, 23(1):48–55. 44. Tóth G, Gáspári Z, Jurka J: Microsatellites in different eukaryotic genomes: survey and analysis. Genome Research 2000, 10(7):967–981. Page 11 of 12 45. Kantety RV, La Rota M, Matthews DE, Sorrells ME: Data mining for simple sequence repeats in expressed sequence tags from barley, maize, rice, sorghum and wheat. Plant Mol Biol 2002, 48(5):501–510. 46. Morgante M, Hanafey M, Powell W: Microsatellites are preferentially associated with nonrepetitive DNA in plant genomes. Nat Genet 2002, 30(2):194–200. 47. Temnykh S, DeClerck G, Lukashova A, Lipovich L, Cartinhour S, McCouch S: Computational and experimental analysis of microsatellites in rice (Oryza sativa L.): Frequency, length variation, transposon associations, and genetic marker potential. Genome Res 2001, 11(8):1441–1452. 48. Ferguson M, Burow M, Schulze S, Bramel P, Paterson A, Kresovich S, Mitchell S: Microsatellite identification and characterization in peanut (A. hypogaea L.). Theor Appl Genet 2004, 108(6):1064–1070. 49. Hopkins M, Casa A, Wang T, Mitchell S, Dean R, Kochert G, Kresovich S: Discovery and characterization of polymorphic simple sequence repeats (SSRs) in peanut. Crop Sci 1999, 39:1243–1247. 50. Luo M, Dang P, Guo BZ, He G, Holbrook CC, Bausher MG, Lee RD: Generation of expressed sequence tags (ESTs) for gene discovery and marker development in cultivated peanut. Crop Sci 2005, 45(1):346–353. 51. Cuc L, Mace E, Crouch J, Quang V, Long T, Varshney R: Isolation and characterization of novel microsatellite markers and their application for diversity assessment in cultivated groundnut (Arachis hypogaea). BMC Plant Biol 2008, 8(1):55–55. 52. Milla S, Isleib T, Stalker H: Taxonomic relationships among Arachis sect. Arachis species as revealed by AFLP markers. Genome 2005, 48(1):1–11. 53. Gupta PK, Varshney RK: The development and use of microsatellite markers for genetic analysis and plant breeding with emphasis on bread wheat. Euphytica 2000, 113(3):163–185. 54. Weber JL: Informativeness of human (dC-dA)n · (dG-dT)n polymorphisms. Genomics 1990, 7(4):524–530. 55. Koppolu R, Upadhyaya H, Dwivedi S, Hoisington D, Varshney R: Genetic relationships among seven sections of genus Arachis studied by using SSR markers. BMC Plant Biol 2010, 10(1):15. 56. Krapovickas A, Gregory W: Taxonomia del genero Arachis (Leguminosae). Bonplandia 1994, 8:1–186. 57. Simpson CE: Pathways for introgression of pest resistance into Arachis hypogaea L. Peanut Sci 1991, 18(1):22–26. 58. Singh AK: Utilization of wild relatives in the genetic-improvement of Arachis hypogaea L. 8. Synthetic amphidiploids and their importance in interspecific breeding. Theor Appl Genet 1986, 72(4):433–439. 59. Krishna G, Zhang J, Burow M, Pittman R, Delikostadinov S, Lu Y, Puppala N: Genetic diversity analysis in valencia peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) using microsatellite markers. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2004, 9:685–697. 60. Palmieri D, Bechara M, Curi R, Gimenes M, Lopes C: Novel polymorphic microsatellite markers in section Caulorrhizae (Arachis, Fabaceae). Mol Ecol Notes 2005, 5:77–79. 61. Palmieri D, Hoshino A, Bravo J, Lopes C, Gimenes M: Isolation and characterization of microsatellite loci from the forage species Arachis pintoi (genus Arachis). Mol Ecol Notes 2002, 2:551–553. 62. He G, Meng R, Newman M, Gao G, Pittman R, Prakash C: Microsatellites as DNA markers in cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). BMC Plant Biol 2003, 3:3–3. 63. Nagy ED, Guo Y, Tang S, Bowers JE, Okashah RA, Taylor CA, Zhang D, Khanal S, Heesacker AF, Khalilian N, et al: A high-density genetic map of Arachis duranensis, a diploid ancestor of cultivated peanut. BMC Genomics 2012, 13(1):469. 64. Becker J, Vos P, Kuiper M, Salamini F, Heun M: Combined mapping of AFLP and RFLP markers in barley. Mol Genet Genomics 1995, 249(1):65–73. 65. Menéndez CM, Hall AE, Gepts P: A genetic linkage map of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) developed from a cross between two inbred, domesticated lines. Theor Appl Gen 1997, 95(8):1210–1217. 66. Stalker HT, Dhesi JS, Parry DC: An analysis of the B genome species Arachis batizocoi (Fabaceae). Plant Syst Evol 1991, 174:159–169. 67. Stalker HT, Dalmacio RD: Karyotype analysis and relationships among varieties of Arachis hypogaea L. Cytologia 1986, 58:617–629. 68. Holbrook CC, Stalker HT: Peanut breeding and genetic resources. Plant Breeding Reviews 2003, 22:297–355. 69. Stalker HT, Dhesi JS, Kochert D: Genetic diversity within the species Arachis duranensis Krapov. & W.C. Gregory, a possible progenitor of cultivated peanut. Genome 1995, 38(6):1201–1212. Guo et al. BMC Genomics 2012, 13:608 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/13/608 Page 12 of 12 70. Jurka J, Pethiyagoda C: Simple repetitive DNA sequences from primates: Compilation and analysis. J Mol Evol 1995, 40(2):120–126. 71. Rozen S, Skaletsky H: Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Meth Mol Biol 2000, 132:365–386. 72. Whitelaw CA, Barbazuk WB, Pertea G, Chan AP, Cheung F, Lee Y, Zheng L, van Heeringen S, Karamycheva S, Bennetzen JL, et al: Enrichment of genecoding sequences in maize by genome filtration. Science 2003, 302 (5653):2118–2120. 73. Orita M, Iwahana H, Kanazawa H, Hayashi K, Sekiya T: Detection of polymorphisms of human DNA by gel-electrophoresis as single-strand conformation polymorphisms. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 1989, 86(8):2766–2770. 74. Murray MG, Thmposon WF: Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 1980, 8(19):4321–4325. 75. Don R, Cox P, Wainwright B, Baker K, Mattick J: ‘Touchdown’ PCR to circumvent spurious priming during gene amplification. Nucleic Acids Res 1991, 19:4008. 76. Lander ES, Green P, Abrahamson J, Barlow A, Daly MJ, Lincoln SE, Newburg L: MAPMAKER: An interactive computer package for constructing primary genetic linkage maps of experimental and natural populations. Genomics 1987, 1:174–181. 77. Lincoln SE, Daly MJ, Lander ES: Constructing genetic maps with MAPMAKER/EXP 3.0 Manual. Cambridge: Whitehead Institute; 1992. 78. Kosambi DD: The estimation of map distance from recombination values. Ann Eugen 1944, 12:172–175. 79. Voorrips RE: MapChart: Software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J Hered 2002, 93:77–78. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-13-608 Cite this article as: Guo et al.: Comparative mapping in intraspecific populations uncovers a high degree of macrosynteny between A- and B-genome diploid species of peanut. BMC Genomics 2012 13:608. Submit your next manuscript to BioMed Central and take full advantage of: • Convenient online submission • Thorough peer review • No space constraints or color figure charges • Immediate publication on acceptance • Inclusion in PubMed, CAS, Scopus and Google Scholar • Research which is freely available for redistribution Submit your manuscript at www.biomedcentral.com/submit