1 sustainable reclamation in golf course design

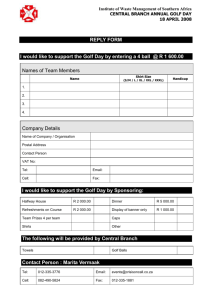

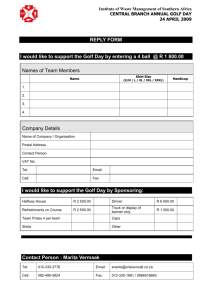

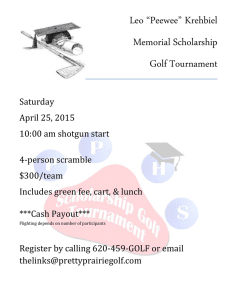

advertisement