THE MIT JAPAN RAM

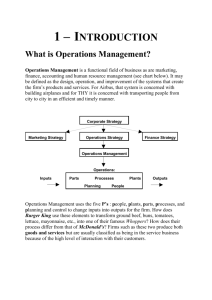

advertisement