CollaboRhythm: New Paradigms in Doctor-Patient Interaction

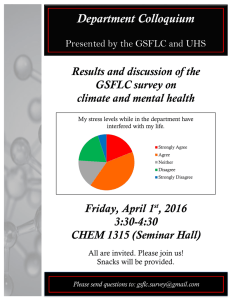

advertisement