POST-DISASTER REDEVELOPMENT PLANNING A Guide for Florida Communities

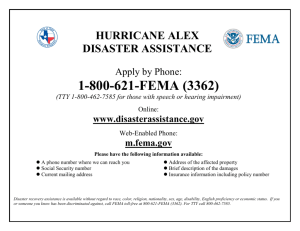

advertisement