Document 11185755

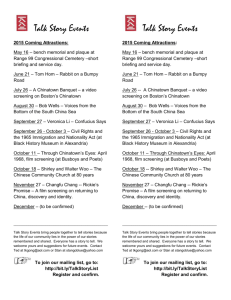

advertisement