Expectations Across Entertainment Media

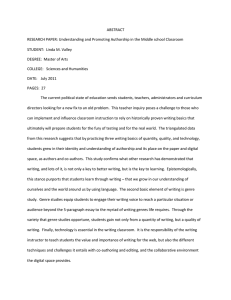

advertisement