Document 11185708

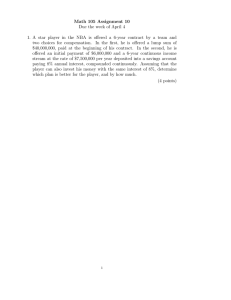

advertisement