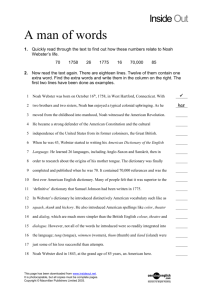

CDC The Lessons of the Siochain Rental ... Mark R. Ellerbrook 1995

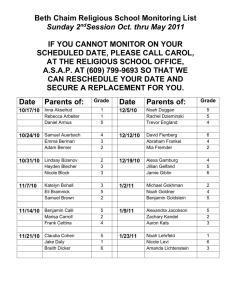

advertisement