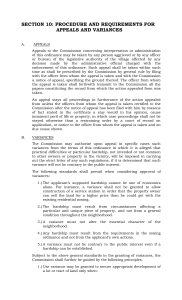

APPEALS IN OPERATION COLLEGE Signature of Author

advertisement