Urban Density Measures in Planning for the Pearl...

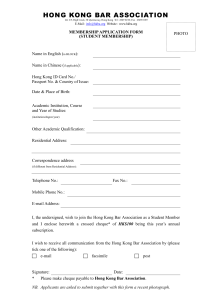

advertisement