Economies of Scale in Rental Housing By

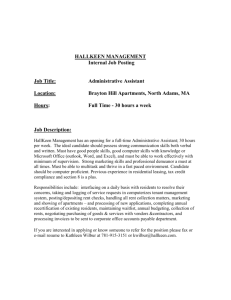

advertisement