FAMILIES LasFamilias KEEPING CONNECTED

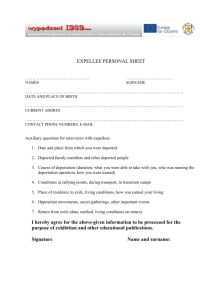

advertisement

CENTER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS & INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE BOSTON COLLEGE post-deportation human rights project KEEPINGFAMILIESCONNECTED manteniendo aLasFamiliasconectadas annual report 2008-2009 about the POSTHUMAN Longtime legal residents can now be deported from the United States on the basis of relatively minor criminal convictions without any opportunity to present evidence of their family ties, employment history or rehabilitation. Their family members must cope with the devastating loss of a spouse, parent, or child, and often with the <inancial loss of a breadwinner as well. RIGHTS The Post-­‐Deportation Human Rights Project offers a novel and multi-­tiered approach to the problem of unlawful and harsh DEPORTATION PROJECT deportations from the United States. Through direct representation, research, legal and policy analysis, training programs, as well as outreach to lawyers, community groups, and policy-­makers, its ultimate goal is to reintroduce legal predictability, proportionality, compassion, and respect for family unity into the deportation laws and policies of the United States. The Post-­‐Deportation Human Rights Project is part of Boston College’s Center for Human Rights & International Justice. F A C U L T Y D I R E C T O R S A D V I S O R Y B O A R D organizations for identification purposes only Daniel Kanstroom B OSTON COLLEGE Deborah Anker, Harvard Law School Judy Rabinovitz, ACLU Immigrant Rights Project Jacqueline Bhabha, Harvard Law School Fr. Richard Ryscavage, Center for Faith in Public Life, Fairfield University Law School Director, International Human Rights Program Associate Director, Center for Human Rights & International Justice M. Brinton Lykes B OSTON COLLEGE Fr. J. Bryan Hehir, John F. Kennedy School of Government Lynch School of Education Professor of Community-­Cultural Psychology Associate Director, Center for Human Rights & International Justice A F F I L I A T E D F A C U L T Y Qingwen Xu B OSTON COLLEGE Graduate School of Social Work Kevin R. Johnson, UC Davis School of Law Howard A. Silverman, Ross, Silverman & Levy Hon. William P. Joyce (Ret.), Joyce & Associates, PC Jay W. Stansell, Federal Public Defender–Seattle Main Office Kalina M. Brabeck R HODE ISLAND COLLEGE Michelle Karshan, Alternative Chance Department of Counseling, Educational Leadership & School Psychology Dan Kesselbrenner, National Immigration Project S U P E R V I S I N G A T T O R N E Y S Anibal Lucas, Organización Maya K’iche’ Rachel E. Rosenbloom B OSTON COLLEGE Nancy Morawetz, New York University School of Law Post-­Deportation Human Rights Project Mary Holper B OSTON COLLEGE Aarti Shahani, Families for Freedom Immigration and Asylum Project Carola Suarez-­‐Orozco, New York University Marcelo M. Suarez-­‐Orozco, New York University Manuel D. Vargas, Immigrant Defense Project Michael Wishnie, Yale Law School English to Spanish Translation: Carolina Carter Design: Zac Willette C O M M U N I T Y P A R T N E R S Inglés en Acción English for Action 2 phone +1.617.552.9261 fax +1.617.552.9295 email pdhrp@bc.edu web www.bc.edu/postdeportation Centro Presente CENTER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS AND INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE AT BOSTON COLLEGE Organización Maya K’iche’ 140 Commonwealth Avenue Chestnut Hill, MA 02467 USA EXPLORING THE IMPACT OF DEPORTATION ON GUATEMALAN AND SALVADORAN IMMIGRANT FAMILIES: PDHRP M eetin g, OMK-BC , New Bedf ord PARTICIPATORY ACTION RESEARCH IN THE POST-DEPORTATION HUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT M. Brinton Lykes and Kalina M. Brabeck WHAT WE DID During 2008 the Center for Human Rights and International Justice (CHRIJ) at Boston College, Centro Presente, and Organización Maya K´iche´ developed a participatory action research project that involved Guatemalan and Salvadoran families living in Rhode Island and Massachusetts. The project documented these families’ experiences of migration to and deportation from the United States. The project also aimed to strengthen the leadership and advocacy skills of immigrants within New England, and to educate the wider public about immigrants’ experiences. The project began with a series of meetings among representatives from the collaborating organizations to strengthen existing relationships, identify shared goals, and design a study into the effects of detention and deportation. Community leaders from Centro Presente and Organización Maya K´iche´ then identi<ied immigrant families to interview who had: 1) the ability to strengthen the organization’s leadership, 2) been directly or indirectly affected by detention or deportation, and 3) children who were living with them in the United States. Collaborators held meetings throughout the project to discuss ongoing issues and to identify action steps. Two-­‐person, bilingual (Spanish-­‐English) research teams conducted open-­‐ended interviews with eighteen families (67% Guatemalan and 33% Salvadoran). Each research team included a social science researcher and a lawyer or law student. Of the families interviewed, eight families (44%) had experienced the deportation of an immediate or extended family member. Six families (33%) had an immediate family member detained. Three families (17%) had undocumented children in the United States. Seven families (39%) had both U.S.-­‐born children and children living in their country of origin. The interviews were designed to elicit participants’ experiences in their own words. Interviews were tape-­‐recorded, transcribed by native Spanish speakers, and analyzed by the CHRIJ researchers. WHAT WE LEARNED The parents we interviewed perceived the current threats of deportation in three different ways: historically (that is, as related to past threats), socially (that is, as threats to family and community), and transnationally (that is, as threats to family in the country of origin). These are described in more detail below. Poverty and Violence: Families identi<ied poverty and violence in their countries of origin as reasons that they decided to migrate to the United States. Fifteen families (83%) named poverty as the main reason for migrating to the United States. Nine families (50%) discussed the fear, silence, and displacement of their families that took place during la violencia (the years of state-­‐sponsored violence and war in Guatemala and El Salvador). Eight families (44%) reported the murder of an immediate family member during la violencia. Four participants (22%) described decisions to migrate to the United States as related to the loss of family, safety, land, and community that followed from la violencia. Experiences of Migration: Participating families made dif<icult decisions to migrate within national borders (to Yincas or to capital cities) and beyond them (to Mexico or the United States). Migration resulted in the separation of family members, including parents from children. Migrants sought work to support their families; but, migration produced feelings of isolation, loneliness, and sadness. Interviewees observed the irony of having fought to reunite their families in the United States after migration, only to face being deported and torn apart again. Thirteen families (72%) discussed the emotional pain of separation caused by migration. Seven families (39%), who had children “there” and “here,” experienced what one participant described as “a heart divided.” Families also described the ways that they maintain connection with loved ones. Threats of Deportation: Participants talked about the ways in which their families had been affected by recent continued on page 9 3 RESTORING JUSTICE AND FAIRNESS TO OUR DEPORTATION LAWS Daniel Kanstroom and Rachel Rosenbloom O ver the past two decades, deportation laws have grown steadily harsher. In particular, two sweeping laws that Congress passed in 1996 – the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA) and the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA)–changed many of the rules governing deportation. As a result, hundreds of thousands of people have been arrested and deported, including many thousands with “green cards.” Many have left behind families in the United States and will never be able to return to this country. The law is especially harsh for undocumented immigrants. People may be arrested without warrants and deported after fast-­‐track proceedings called “expedited removal” in which they may never see a judge. The new laws also make it much harder for an immigration judge to give someone the chance to stay in the United States based on length of residence, family ties, and other humanitarian factors. Even those who legitimately fear persecution in their home countries may be barred from applying for asylum because of new time limits. Another harsh aspect of the new laws is “return bars”: someone who has spent more than 180 days in the United States without lawful status and then leaves the country is barred from returning for three years. She will be barred for ten years if she was in the United States for a year unless she can obtain a waiver, which is available only in very narrow circumstances. This means that someone who is eligible for an immigrant visa through marriage or employment may end up locked out of the United States for ten years when she leaves the country to apply for a visa at a U.S. consulate abroad. Legal permanent residents (“green card holders”) who have criminal convictions have also been severely affected by the 1996 laws. Before 1996, most longtime legal residents in deportation proceedings could ask the immigration judge for the chance to remain in the United States based on family ties, rehabilitation, or other factors. These days, however, even a minor crime such as petty larceny can result in mandatory deportation and a 4 lifetime bar from returning. Many of the people affected by these laws came to the United States as young children and got into trouble with the law as teenagers. Some were never even sentenced to any time in jail. Others have served their time and gone on to become valued members of their communities. Yet the law allows no way for the immigration judge to consider any of these factors. In addition, the new laws require that those with criminal convictions be incarcerated while their cases are being heard. Many people with strong cases give up <ighting for the chance to stay in the United States because they just cannot tolerate spending months and potentially years in detention. Along with these changes to the law, enforcement efforts have dramatically increased against both undocumented and documented immigrants. Workplace raids have led to the arrest and detention of thousands of people over the last few years, including parents of young U.S. citizen children. House-­‐to-­‐house raids that supposedly target “violent gang members” in fact sweep up many bystanders who simply happen to be undocumented. Because of new cooperation agreements between ICE and state and local law enforcement, getting stopped for a minor traf<ic infraction can be the <irst step along the way to deportation proceedings. The increase in detention and deportation is staggering. In 1994, immigration authorities detained about 5,500 noncitizens on an average day. That daily average quadrupled to over 20,000 by 2002, with over 200,000 people detained in the course of the year. In 2008, the overall number of detentions was 407,000. From 2000 through 2007, the total number of “deportable aliens” caught within the United States and expelled was over 9 million (including formal removals and “voluntary departures”). One can only estimate the number of family members, both citizens and non-­‐citizens, currently affected by this system. Valued members of our communities have been suddenly uprooted, without warning. Children have witnessed their homes being searched in the middle of the night and their parents being taken away in handcuffs. The effects of having a parent or other loved one deported are traumatic, and can be unimaginably tragic. In October, 2004, Elary Jeffers was deported from Boston to the Caribbean island of Nevis. His four year old son, Dontel, had primarily lived with his father, but he stayed behind. His mother took custody of the boy but Dontel was soon placed in foster care due to his mother’s drug abuse. Four months later, the smiling face of Dontel Jeffers appeared on the front page of the Boston Globe for a terrible reason: he had allegedly been beaten to death by the foster parent. Antonio Mosquera was deported from Los Angeles to Colombia after thirty years in the United States. He left behind a wife and four children, all U.S. citizens. His seventeen-­‐year-­‐old son became depressed over the loss of his father and committed suicide three months later. Mr. Mosquera was not even allowed back in the country to attend the funeral. The Obama administration has signaled that it will end large-­‐scale workplace raids and seek passage of “comprehensive immigration reform” by Congress. These are encouraging signs, but they are just the <irst step. In order to restore fairness and proportionality to our deportation laws, we must seek fundamental changes that address the problems facing both undocumented immigrants and legal permanent residents. Necessary reforms include ending the backlogs for immigrant visas, providing a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants, eliminating the “return bars,” and bringing our asylum laws in line with international standards. We must also address the punitive detention and deportation laws that affect legal permanent residents who have committed minor crimes. Deportation proceedings should not be triggered by minor convictions, and all those facing deportation must be given the opportunity to establish that they are not harmful to society and deserve the chance to remain with their families in the United States, as well as the right to be released while their case is under consideration. Finally, we need our legal system to be open to cases brought by deportees where mistakes were made or where unusually harsh consequences have affected them or their families. Until all of these aspects of our current laws are addressed, families and communities will continue to be needlessly torn apart and deportation will remain a cruel and unjust system. 5 ORGANIZING WORK IN THE IMMIGRANT COMMUNITY: EXPERIENCES OF CENTRO PRESENTE Gabriel Camacho C entro Presente is a Latin American immigrant-­‐based community organization that was founded in 1981. It now represents one of the largest organized immigrant communities in Massachusetts. At the organization’s 2008 General Assembly we discussed what the installation of President Barack Obama’s administration may mean for the immigrant community. We also considered the current economic crisis and President Obama’s campaign support for comprehensive immigration reform. We broke into small groups to discuss these issues within this context. To do so we utilized Centro Presente’s model for engagement and empowerment of the immigrant community. In this process, active community members form equipos de trabajo (work teams). The equipos are organized around topics such as Labor, Civic Engagement, and Know Your Rights. Each equipo nominates a representative to the Board of Directors. Equipo leaders then lead discussions among community members. In March of 2008 Centro Presente formed a Know Your Rights team roughly modeled after the AFSC’s Immigrant Safety Network training. The model combines legal, media, community, and local government strategies in order to create comprehensive response to raids. Because immigrant communities continue to face workplace and residential raids we must provide our community members with basic knowledge on what to do (and not do) in the event of a raid. Centro Presente is now sharing its resources and leadership with English for 6 PD HRP Work shop, CP Action, -BC, Som erville Organización Maya K’iche’ and Boston College by collaboratively facilitating Know Your Rights workshops with them in each of our communities. As we moved into 2009 we hoped for “change,” or at least a moratorium on the raids. To our great disappointment, however, we have witnessed an upswing in residential raids. As a result, in April Centro Presente announced to the press that it would intensify its Know Your Rights trainings. In addition, the Chelsea Collaborative, a sister organization, called for a community meeting with ICE. At the public meeting Centro Presente joined the Collaborative and our community members in denouncing recent enforcement practices and agents’ behaviors toward immigrants. Centro Presente has also been monitoring developments in Washington, D.C., as more attention is placed on possible immigration reform. We are keenly aware that mbly Centro Presente General Asse lawmakers must hear the voices of our community, not just those of politicians, media pundits, and industry lobbyists. To this end Centro Presente and other member organizations of the Massachusetts chapter of the National Alliance of Latin American and Caribbean Communities (NALACC) are combining forces to visit our congressional delegation. In this meeting we plan to impart our vision of just and humane immigration reform. Centro Presente and NALACC place our immigrant rights movement within the international context of foreign policy and the globalized economy. The immigration debate in the United States too often ignores this context, but our community members are well aware of the “push and pull” factors of the migration equation. Centro Presente is proud to participate in the Post-­‐Deportation Human Rights Project. We believe that collaborative research projects with academia can provide institutional validity to our grassroots advocacy. The CHRIJ has documented the testimonies of community members who have been detained and deported and explored the “push” factors from sending countries. As we continue our collaborative Know Your Rights training, we encourage institutions of higher learning to defend human rights at home and abroad. Gabriel Camacho is President of the Centro Presente Board of Directors kshop, CP- PDHRP Wor ville BC, Somer 7 KNOW YOUR RIGHTS: REPORT FROM A WORKSHOP Juan Manuel Leon Parra T he PDHRP’s four collaborating organizations have been working to develop community-­‐based Know Your Rights workshops. These workshops draw on participatory pedagogy and theater. They aim to foster grassroots leadership and critical consciousness among participants. In the workshops undocumented immigrants develop a deeper understanding of their human rights and discuss how to effectively respond to the threat of deportation and detention in the United States. Seventy people attended the <irst collaborative Know Your Rights workshop, which was held in Providence, Rhode Island on ERE:RECHOS L L A D EL DTO SUS D NDOANOCIEN E G C A 2009 ABRIL , RI 5 DE ce iden DO, 2 Prov t, SABA S EFA) osuth s sable 60 K a una hora espon 5 1 s cad ida (R 12 a inuto - Com s3m cione partir aniza ) - Com 4 org Parra nida s e v la n ie l León es: de anue PM B ción an M anizacion senta 12:45 Ju : a re ia p rg 0 e mon 12:0 las O Brev e Cere tación de 0 PM P stro d n a 1:0 (Mae de prese Senior - C MK 12:45 ollege Orden Beatriz Ventura - O- Boston C ” n Latina s Adria nton Lyke s - EFA cción ) ri te tral “A B n . M o Tea ble EFA Cifue p a n s ru o n G rl o : p Ma e EFA (Res abajo tral d a tr e te d ! rupo lugar ifras! del g en el s-C dada ación s) toria Actu una re migra ifuente ntan eyes rlon C 0 PM L se a re :2 M l p 1 : a te a Re nte ollege ctu sen 1:00 adela rio a o Pre ; Boston C uí en Centr igrato C ) de aq enior/ olbert/IM ma m S ia le CP n ra iz o o tr m onsab by C Pan Bea e Cere (Resp nte – ence – Ab a 1:40 PM stro d d ights Prese (Mae en: entro a de Provi Your R C 1:20 w n in o o n d Exp 10 m Aboga os!/K .UU? in erech e) los EE 10 m Tus D Colleg ión en onoce ortac oston A’s ¡C ble B e dep ciones? ? L a d s IR s n H a o sp nta lític aza D: C s (Re les po y las prese sta amen el DV gunta e actua ión d 3 pre n las de la obradernos de entac mina rupos/ Pres discri n después er y defen sub-g o PM 6 n 5 n e o eda ond fecta a 1:5 sión r grup nos a as nos qu para resp 1:40 Discu es po d nera a acion e ma des o du n concreto 5 PM e cad rganiz tu e De qu a 2:1 nte d ntes o " ¿ ue inquie os hacer 1:55 re senta e s if Q uto repre de d in n s " ¿ ue podem m U . re 2 a do Q ) lenari guntas. urante nima "¿ sente blea p pre nes d s-2a o Pre lusio asam ndo a las grupo Centr conc lidad ie 6 sub nsable moda respond e sus o n n p o e s p e s a s (R po ex uesta asamble la folleto y resp ’ subgru ntas elante de ’ iche Cada os” y pregu d aya K erech PM hacen ión estará ión M 2:50 mis d c e “ a a S e 5 iz c d iza 2:1 tas rgan e O rj s organ e , ta joven riales e los mate ral d ga de cultu Entre Baile e d PM n 0 ente ió a a 3:0 s. ectam entac pedid 2:50 ar dir s pregunta Pres - Des nvers aller 5 PM e a co almente su T u :1 l rq 3 e a ace dividu ed se 3:00 e in u Cierr rán aq PM 3:15 8 de te la gen s que aten vita a Se in s panelista con lo Dram atiza tio n of B ianco Raid, KYR W orksh April 25, 2009. The op workshop began with a dramatization of a raid and a presentation by an organization’s leader and an immigration lawyer. Then, in small group discussions, participants described the factors that pushed them to migrate, their desire to work, and the importance of creating alliances and community networks. One of the participating leaders of the Organización Maya K’iche described undocumented immigrants’ realities as “the hardest pain that exists here in the United States.” Carlos Ixen, a volunteer of Centro Presente, added that he has witnessed “many families…in panic. They have a great fear of the police or people in uniform.” The next two workshops will be held in Somerville and New Bedford. The program’s goal is to continue this process of self-­‐education and to expand a critical consciousness among our members and in the U.S. society more broadly. As Marlon Cifuentes, from English for Action, stated, “There is much to do. We must not rest until we have a migratory reform signed by President Obama.” e PDHRP Meeting, CP-BC, Cambridg EXPLORING THE IMPACT OF DEPORTATION ON GUATEMALAN AND SALVADORAN IMMIGRANT FAMILIES continued from page 3 changes in attitude, practices, and policies toward immigrants in the United States. Fourteen families (78%) described the experience and/or threat of detention and deportation as creating disruption to their family. Eight parents (44%) reported that actual or threatened separation from deportation affected their children’s well-­‐being. Parents reported children’s experiences of academic problems, sadness, crying, sleep and appetite loss, insecurity about the future, worry, fear, nightmares, speech dif<iculties, withdrawing, and tantrums. Parents also described their own sadness, loss of energy, hopelessness, crying, anxiety, lost sleep, weight loss and gain, anger, fear, distrust, nightmares, and worry. They talked about living every day in a state of vulnerability and insecurity. Parents noted that these feelings affected their interactions with their children and the children’s development. Connections between Deportation and “La Violencia”: Families in this project linked the current threats to their families posed by deportation to a history of con<lict and terror in their countries of origin. They described similarities between the current environment in the United States of fear, silence, anxiety, and suspicion and the climate in their countries of origin during la violencia. One participant described deportation as “the second war.” WHERE WE GO FROM HERE Post-­‐Deportation Human Rights Project collaborators now have a deeper understanding of how uncertainty, fear, and mistrust related to deportation negatively affect immigrant families’ lives, work, and child-­‐rearing, in their own words. Through the interviews we have also identi<ied connections between these families’ current experiences and their histories of violence, poverty, and family separations and migrations. The <indings from the interviews will be presented to the participating community organizations for their feedback and then presented to the wider public. Preliminary conclusions are guiding our current work. We have developed and distributed a survey to over 100 Latino immigrant adult parents of children living in the United States. The survey was designed to assess the effects of detention and deportation policies and practices on a larger group of Latino immigrant parents and their children. We initiated research with “sending families” in Zacualpa, El Quiche, Guatemala. We will also continue strengthening our partnerships and engaging together in legal representation, education, advocacy, and organizing. For example, the CHRIJ, Centro Presente, English for Action, and Organización Maya K´iche´ recently facilitated a participatory Know Your Rights workshop with immigrants. These activities are discussed in more detail throughout the Report. 9 TRANSNATIONAL LINKS: CHESTNUT HILL TO ZACUALPA AND BACK Rachel Hershberg and Ana Gutiérrez D uring the summer of 2008 a team of law and social science researchers from the Center for Human Rights and International Justice (CHRIJ), an anthropology student from Landivar University in Guatemala City, and community members and researchers from Zacualpa, El Quiché and its villages collaborated in a new phase of the Post-­‐Deportation Human Rights Project. The project aimed to better understand both the reasons that individuals and families migrate to the United States and the impact of U.S. deportation practices on communities in Guatemala. To this end, the team conducted 132 interviews and visited and learned about the history and current reality of Zacualpa and its surrounding areas. Rachel, an Applied Developmental Psychology student from Boston, participated in research interviews with dozens of families. Ana, a community member and researcher from Zacualpa, served as a key informant, guide, and interpreter. Poverty, war, migration and deportation have ruptured generations of family relationships in Guatemala. Poverty and limited employment and educational opportunities in Guatemala push many to migrate. The interviewed families described how necessity propels some people to decide to incur large debt, leave family and community behind, and make the dangerous journey north. In the United States, many migrants work in factories and processing plants that require long hours of dif<icult work under dangerous conditions. In their places of employment, migrants’ basic rights are frequently violated. In their day-­‐to-­‐day lives migrants live in fear of being arrested, detained, and deported if they lack proper documentation. Remittances that these migrants send from the United States have contributed importantly to rebuilding Zacualpa, which was devastated during the war. Remittances have also allowed families to construct homes. Yet despite these gains it was clear that children and youth need guidance and suffer when their parents and elders leave. Because the family is the nucleus of the community, when families are forced to migrate in search of resources, the individual family as well as the entire community are affected. In re<lecting on the stories she Home, Trapachitos 10 II PDHRP Team heads out for interview with deported family heard, Ana became more deeply aware of the complex familial, social, spiritual, and economic effects of migration and deportation on her transnational community. She saw more clearly that we all are immigrants at some point in life; we are not permanent owners of the place where we reside, but rather pilgrims, not knowing when we will be welcomed and when rejected. Rachel learned about the complex factors affecting Guatemalan families, as well as the resilience and strength of the K’iche’ people. She also recognized how sometimes those in the United States cannot fully imagine the life and poverty in Guatemala. The authors found through this collaborative work that when people come together they can respond more fully to the challenges of transcending borders, color, language, upbringing, and culture to generate transnational projects that defend our rights and shared humanity. To respond to the realities uncovered in these interviews, the CHRIJ and a local team of Zacualpan leaders and religious workers, supported by the Social Programs of the Franciscan Order, the parish, and a generous anonymous grant, will initiate a Center for Immigrants in Zacualpa. The Center will serve as a resource to those who migrate and those who return – voluntarily or involuntarily – as well as a base for organizing self-­‐help groups in the villages. The CHRIJ hopes to supervise Parish ch u rch and M e morial to those as sassinate d and dis appeared March 16 , 1981, San Anto nio Sinac he 11 STAFF ANNOUNCEMENTS ✂ Please make checks payable to Boston College and write CHRIJ in the memo line. All donations are tax-­‐deductible. Thank you for your support! Count me in! Enclosed in my donation of: 50# 100 # Laura Murray Tjan, J.D., has joined the Boston College Law School faculty as a Visiting Assistant Clinical Professor in the law school’s immigration clinic, replacing Mary Holper. Mary is now on the faculty of Roger Williams University School of Law. Erzulie Coquillon, M.A., J.D., will be collaborating with the PDHRP as a Visiting Scholar of the Center for Human Rights and International Justice for 2009-­‐2010. 500 # 1000 # Please contact me to discuss taking on a pro bono case or serving as a legal resource on: Motions to Reopen Consular Processing/NIV Waivers Post-­Conviction Relief I have a post-­‐removal case that I would like to discuss. Please contact me. Maunica Sthanki, J.D., has joined the PDHRP as a Supervising Attorney, replacing Rachel Rosenbloom, who is now on the faculty of Northeastern University Law School. 250# Name Organization Address Phone Email post-­‐deportation human rights project CENTER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS AND INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE 140 Commonwealth Avenue Chestnut Hill, MA 02467 USA phone fax email web +1.617.552.9261 +1.617.552.9295 pdhrp@bc.edu www.bc.edu/postdeportation +1.617.552.9261 pdhrp@bc.edu www.bc.edu/postdeportation 140 Commonwealth Avenue Chestnut Hill, MA 02467 USA CENTER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS AND INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE post-­‐deportation human rights project 12 phone email web Inspired to make a tax-deductible donation to the Post-Deportation Human Rights Project?