Historical and Cultural Narratives in Landscape Design: Florida

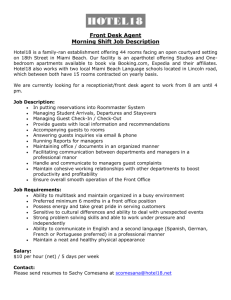

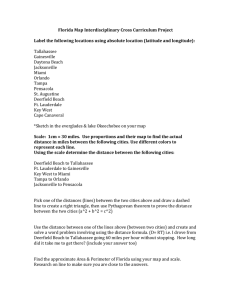

advertisement