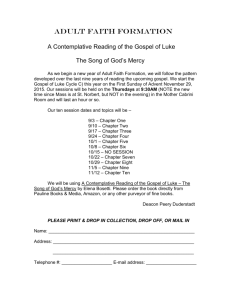

10 Sunday in Ordinary Time – Year C

Our Lady of Lourdes Church; Massapequa Park, NY

9 June 2013; 10:30 a.m. mass

10 th

Sunday in Ordinary Time – Year C

1 Kings 17:17-24; Psalm 30; Galatians 1:11-19; Luke 7:11-17

The great temptation when we hear a miracle story of Jesus is to ask the question “How?”

The better question is “Why?”

Of course, it’s natural to ask “how.”

This would surely be the question I would pose if I saw a contemporary equivalent of today’s gospel, say, someone running out of the Massapequa Funeral Home on to

How did that happen?

Park Boulevard shouting, “He’s alive!” or “She has risen!”

How did the doctor or the undertaker make such an outrageous mistake?

How in the world does someone go from being dead to being alive?

How questions are supposed to come to mind for miracle stories.

If they did not, then we would have good reason to doubt that the stories are about miracles in the first place.

But as I say, asking this question, asking how, is a temptation because the miracle stories yield their richest fruits when we ask why .

The why I have in mind is not why did Jesus do this, but rather, why did the evangelist tell us about it.

Initially, the answer seems simple enough: being risen from the dead was probably as rare in first century Palestine as it is in twenty-first century Massapequa Park, or wherever home is for you.

But this sort of a response reads today’s gospel more as a journalist’s account of events than as a lesson intended to guide the church’s life of faith.

After all, in John’s gospel, we read,

“Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of [his] disciples that are not written in this book” (Jn. 20:30) , or in any book, for that matter.

Why, we can ask of a miracle, is this sign , written in this book?

My answer? Because the miracle stories show us something about who God is.

Why does Luke tell us about the raising of the son of the widow of Nain, the gospel that Quentin just read?

My answer? Because this story reveals our God to be a God of mercy.

It is worth our time to get clear on what exactly mercy is, especially since we have been talking about it so much.

Already, the word “mercy” has been uttered nine times since this mass started, and I am not counting its appearances in my lengthy introduction earlier or even in this homily so far.

The liturgy itself up to this point has included the word that many times, and we still have a solid two hours left to go!

Today’s gospel does not include the word, but it does define it.

And its definition is not what we are used to hearing.

Customarily, we think of mercy as a negative word, in the sense that it describes a non-action on our part.

A police officer shows mercy to a speeding motorist when he makes a ticket turn magically into a stern warning.

We might think that this is the mercy the church has in mind when she has us say,

“Lord, have mercy,” “Christ, have mercy,” “Lord, have mercy,” whenever we go to mass.

In other words, “Lord, do not come down on me like a ton of bricks, like I deserve, but rather, spare me.”

But none of this is Gospel mercy.

Gospel mercy consists of three things: seeing, feeling, and acting.

Think of Jesus today as he encounters this funeral procession led by a grieving widow who,

Luke is careful to point out, has lost “her only son” (Lk. 7:12) , a detail that the Church Fathers seize on as a prefiguring of Mary, the Mother of Mercy.

“When the Lord saw her” (Lk. 7:13) , Luke writes.

Jesus sees the situation before him.

Death, especially death of the young, was all too common in the ancient world, and so it would have been perfectly understandable for Jesus and his disciples to mind their own business and keep walking.

But this is not who Jesus is; this is not who God is.

“When the Lord saw her, he was moved with pity for her” (Lk. 7:13) , Luke continues.

That phrase, “moved with pity,” if it were translated literally, could be rendered, “felt it in the guts.”

There was something about this scene, this profoundly sad situation, that made Jesus feel something in his guts .

His seeing was not just a glancing; it was a penetration into the heart of what was happening.

One cannot look at people that way without feeling it, sometimes right in the guts.

The story concludes, “[Jesus] stepped forward and touched the coffin…and he said,

‘Young man, I tell you, arise!’…and he gave the man to his mother” (Lk. 7:14-15) .

Jesus does not see, then feel, then tuck that away to reflect upon another day.

He acts. Decisively. In that moment.

And that changed everything:

“Fear seized them all…they glorified God…[and a] report about him spread through the whole of Judea and in all the surrounding region” (Lk. 7:16-17) .

If that report were looking to be as brief as possible, it might have said only this: he is merciful.

2

Would that this same report should go out about each of us!

He is merciful!

She sees, feels, and acts out of love for others!

This, I know, is my prayer for myself on my first full day as a priest, that I be merciful to those I encounter, just like Christ was and is so merciful to me.

This is no empty prayer, nor is it reaching for the low-hanging fruit on the tree of virtues.

To see deeply, when we could just as well avert our eyes?

To feel in our guts, when, honestly, we have seen the same situation over, and over again?

To act decisively, when, well, what little good could my action possibly accomplish?

Asking to see, feel, and act in these ways, the ways that God sees, feels, and acts, is a downright dangerous prayer.

It might just be answered.

Sisters, brothers, we break open the Scripture at mass not to bide our time until we get to the main event at the altar.

We break it open to re-member again, and again, and again what sort of God we have.

Today, the message could not possibly be clearer: our God is a God of mercy, one who sees, feels, and acts out of love for us.

And so my prayer, for myself and for you, is as simple as it is dangerous:

Lord, give mercy;

Christ, give mercy;

Lord, give mercy.

3