Document 11163426

advertisement

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011 with funding from

Boston Library Consortium

Member

Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/smoothingsuddensOOcaba

Technology

Department of Economics

Working Paper Series

Massachusetts

Institute of

SMOOTHING SUDDEN STOPS

Ricardo

J.

Caballero

Arvind Krishnamurthy

Working Paper

July

5,

01 -26

2001

Room

E52-251

50 Memorial Drive

Cambridge,

MA 02142

paper can be downloaded without charge from the

Social Science Research Network Paper Collection at

This

http://papers.ssrn.com/paper.taf ?abstract id=276675

T^ssfflilr

Technology

Department of Economics

Working Paper Series

Massachusetts

Institute of

SMOOTHING SUDDEN STOPS

Ricardo

J.

Caballero

Arvind Krishnamurthy

Working Paper

July

5,

01 -26

2001

Room

E52-251

50 Memorial Drive

Cambridge,

MA 02142

paper can be downloaded without charge from the

Social Science Research Network Paper Collection at

This

http://papers.ssrn.com/paper.tafSabstract id=xxxxxx

Smoothing Sudden Stops

Ricardo

J.

Arvind Krishnamurthy*

Caballero

July

5,

2001

Abstract

Emerging economies are exposed to severe and sudden shortages of international

financial resources.

Yet domestic agents seem not to undertake enough precautions

against these sudden stops.

Following our previous work,

the central role played by limited domestic development

in

we

highlight in this paper

ex-ante (insurance) and ex-

post (spot) financial markets in generating this collective undervaluation of external

resources and insurance.

Within

this structure, this

policies to counteract the external underinsurance.

paper studies several canonical

We

do

this

by

first

solving for

the optimal mechanism given the constraints imposed by limited domestic financial

development, and then considering the main - in terms of the model and practical

relevance - implementations of this mechanism.

JEL Codes:

Keywords:

E0, E4, E5, F0, F3, F4,

External shocks, domestic and international collateral, underinsurance,

credit lines, liquidity requirements, asset

'Respectively:

MIT and NBER;

Duke Research Workshop

their

comments, and

Gl

to

market intervention.

Northwestern University.

We

are grateful to the participants at the First

especially to V.V. Chari for

in International Economics, Venice, June 2001, and

Adriano Rampini

for helpful conversations.

Caballero thanks the

Written

support. E-mails: caball@mit.edu, a-krishnamurthy@nwu.edu.

NSF

for the First draft:

for financial

May

2001.

Introduction

1

To a

first

order, an emerging

economy external

can be described as an event

crisis

which a country's international financing needs significantly exceed

its

in

international financial

resources. Given that these events are a "fact-of-life" in these economies, it is puzzling that

domestic agents do not undertake measures to precaution against them. Indeed, quite the

contrary, they often increase the likelihood of these events

booms, contracting dollar

inflow

A common

anticipated

is

and so

explanation for this behavior

official

is

over- borrowing during capital

on.

that

due to distortions created by

it is

interventions, such as crony capitalism, fixed exchange rates,

and IFI's

1

bailouts.

We

liabilities,

by

have argued elsewhere that the external underinsurance problem in these economies

more structural

interventions.

nature than one concludes from just pointing at potentially misguided

in

Underdeveloped financial markets, a basic feature of emerging economies,

leads to a distorted valuation of international resources that in turn leads to external un-

derinsurance. In this paper,

we take

this structure as given,

and explore a

solutions to the underinsurance problem. Since the strategies

ing form

by governments

on which strategies

gies that

in

we

discuss are

emerging markets, our main interest

may work

is

better under different constraints.

work within our model and discuss some of the

series of canonical

difficulties

all

used in vary-

in providing

We

guidance

identify the strate-

they

may

encounter in

implementation.

In our framework,

when a country's international

collateral (or liquidity), the

collateral (or liquidity).

phenomenon.

of this

A

financing needs exceed

domestic price of the latter

rises vis-a-vis

depreciation of the exchange rate, for example,

international

that of domestic

is

a manifestation

2

However, when domestic financial markets are underdeveloped

when

its

the domestic collateral value of projects

is less

—

in

our terminology,

than their expected revenues - agents'

external insurance decisions are distorted.

The reason

external resources cannot transfer the

surplus generated by these resources to other

full

is

that domestic agents in need of

participants in domestic financial markets that do have access to the scarce external funds.

Thus,

in equilibrium,

the scarcity value of external resources

sions are biased against hoarding international liquidity

events.

The underinsurance with

'See. for example,

Krugman

is

depressed, and private deci-

and thereby insuring against these

respect to external shocks takes

(1998), Burnside,

See Caballero and Krishnamurthy (2001c).

Eichenbaum and Rebelo

many

(2000). or

forms:

excessive

Dooley (1999).

external borrowing during booms, a maturity structure of private debt that

toward the short term, dollarization of international

lines,

and

so on.

distorted

is

limited international credit

liabilities,

3

In this paper

we study

in

a unified framework several of the main solutions to this

underinsurance problem. Section 2 presents the environment that we have used in earlier

work, and reproduces the result of collective external underinsurance in the competitive

equilibrium with only spot loan markets.

suppress

all

aggregate shocks.

The

One

reasons

to deal with the underinsurance problem.

is

model

difference in the current

that our focus

To keep matters

is

that

is

we

on domestic arrangements

simple,

we do not

discuss at

all

4

international credit lines and other valuable insurance mechanisms that involve foreigners.

Alternatively, one can think of our discussion as net of these external insurances.

aggregate external constraint will be fully anticipated and

ance, in

its

many

capital inflow

still

A binding

occur. External underinsur-

forms, will simply collapse into excessive international borrowing during

booms.

While aggregate shocks have no

role in the analysis, idiosyncratic ones are central since

they generate the need for domestic financial transactions. Frictions in these transactions

are at the root of the external underinsurance problem.

In section 3,

we show

that

if

domestic agents are able to write complete insurance contracts with each other, the external underinsurance problem disappears.

firms' collateral ex-post,

and hence

More domestic

insurance increases the distressed

their capacity to bid for the external resources held

by

other domestics. In equilibrium, this raises the relative price of international to domestic

collateral, increasing the incentive to

An important

hoard international resources.

aspect of financial underdevelopment, however,

private insurance markets. In section

4,

we assume that

is

the absence of these

idiosyncratic shocks are unobserved

so they cannot be written into insurance arrangements.

We

solve the

mechanism design

problem associated with the private information constraint within our structure, and show

that the social planner can in principle get around this informational constraint and achieve

the competitive equilibrium with complete idiosyncratic insurance markets.

to implementation of the social planner's mechanism.

We

whereby private agents form a conglomerate and extend

this

arrangement

and hence

3

is

is

individually incentive compatible,

it is

We

then turn

begin by analyzing a solution

credit lines to each other.

While

not coalition incentive compatible

not robust to the presence of spot markets, as in Jacklin (1987). Finally

we

See Caballero and Krishnamurthy (2000a) and (2001a).

''See

Caballero and Krishnamurthy (2000a) and (2001b) for discussions of insurance arrangements with

foreigners.

explore two sets of solutions that require government intervention: Capital flows taxation

or

mandated

international liquidity requirements,

and

sterilization of capital inflows.

These

solutions can also work, but they are subject to other forms of the coalition incentive

compatibility problem as well.

A

2

We

model of external underinsurance

begin by laying out the model and describing the external underinsurance in the com-

petitive equilibrium with only spot loan markets. In the next sections

this result

is

by better domestic insurance arrangements, or

affected

we

shall discuss

how

in their absence,

by

centralized arrangements to directly deal with the external underinsurance problem.

The environment

2.1

Consider a three date,

t

classes of agents in the

— 0,

1,2,

economy with a

single

consumption good. There are two

economy: a unit measure each of domestics and

foreigners.

Both

take as objective to maximize date 2 expected consumption of the good,

U=E[c2

Each domestic

is

c2

],

>0.

an entrepreneur /manager who owns and operates a production

nology within a firm. Investing c(k) units of the good at date

where c(k)

is

As part

strictly increasing, positive,

of the

strictly

results in capital of k units,

=

convex with c(0)

0,

—

d(0)

0.

normal ongoing restructuring of an economy, one-half of the firms (ran-

domly chosen) need

j

and

tech-

to re-inject resources into the firm at date 1 to achieve full output. Let

e {i,d} be the type of the firm

at date

1.

Firms that are not

hit

by

this idiosyncratic

shock are i-types ("intact") and go on to produce date 2 output of Ak. Firms that receive

Their output

the shock are d-types ("distressed").

units of good, the d-firm can obtain

A = A

-

a,

and assume that

7A

A >

that

it

maximum

to ak, but by reinvesting I

additional units of goods at date

With

1.

full

obtains the same output as an intact firm, Ak. In

henceforth drop this

falls

reinvestment, I

all

=

k,

2.

We

< k

normalize

a distressed firm

cases of interest below, I

<

k,

thus

we

reinvestment constraint from our discussion (while ensuring

does not bind in our technical assumptions).

The domestic economy has no goods

at either

are

met by importing goods from abroad, which

We

assume that

or date

1.

All investment needs

are paid for with funds raised from loans.

endowments

foreigners have large

date

of goods at all dates,

and have access to

storage with rate of return one.

Firms face

significant financial constraints. Neither the plants nor their expected

are valued as collateral by foreigners.

with

w

units of a good that arrives at date 2

lender courts.

Instead,

i.e.

we assume that each domestic

and can be pledged

domestics can take out loans against

Tangibly,

bank accounts.

we might think

of

w

w

is

output

endowed

as collateral to a foreign

that will be enforced by international

as revenues from

oil

exports that reside in foreign

Assumption

1

(International collateral)

Domestics may take on loans

ofw, and must

international collateral

collateral.

imperfect in the sense that not

+

the

dij < w.

all

However we

assume

up

to

assume that these contracts are also

Ak

is

collateral.

collateral)

that domestic courts are additionally able to enforce domestic (local) debt con-

an amount of Xak where A

do,i

Assumptions

latter as

shall

of the output of

Assumption 2 (Domestic debt and

tracts

from foreign lenders against

domestic can also take on a loan from another domestic. Unlike foreigners, domestics

do accept the plants as

We

1

satisfy a full collateralization constraint:

doj

A

or date

at either date

1

and 2

are

+

dij

how we

<

1

Thus, the domestic lending constraint

.

< Xak + w -

(do,/

+ di,f)

define an emerging economy. Thus,

an economy where pledgable assets are

is:

limited,

we think

of the

and a large share of these assets

are part of domestic but not international collateral.

We define an external crisis as a date 1

event in which the financing needs of the economy,

\k, exceeds the international financial resources available to

not central to our concerns and results in this paper,

it,

(w - d

we suppress

all

j). Since they are

aggregate shocks.

external crisis happens despite being fully anticipated. This simplifies our discussion

means that

below).

external underinsurance will only take the form of overborrowing at date

With some abuse

underinsurance.

at date

1

The

of terminology,

we

The

and

(see

will continue referring to the latter as external

following assumptions on parameters guarantee that a crisis occurs

in all the equilibria

we study throughout

the paper, and that there

is

external

underinsurance in the spot loan market equilibrium:

Technical Assumptions 1

(1)

(2)

(3)

2.2

C-i^Aa

> „,_ c (c'-i (-$*•))

^-l ^+a+Aa(A-l) Aa <

w _ c (c /-l( ^+MA-l) j^ A

)

(

Xa < 1

,

Spot loan markets

Let us begin by studying the equilibrium

in this

borrowing via a sequence of spot loan contracts.

domestic insurance arrangements.

economy when agents are

Thus what we

restricted to

rule out for

now

are

All of the investment needs of domestics (date

goods from foreigners. The goods are paid

each firm takes on foreign debt at date

a plant of

there

is

A

its

size k.

by

for

1)

have to be met by importing

Suppose that

issuing date 2 debt claims.

of doj and invests

of these resources in building

all

Since firms are ex-ante identical, without loss of generality we can assume

no domestic debt

firm at date

maximum

and date

1

at time

0.

finds itself either distressed or intact.

If distressed, it

borrows up to

international debt capacity in order to take advantage of the high return of

rebuilding/restructuring the firm:

dij

These resources are then invested

After this,

date

1 either,

it

must turn to

— w-

do j.

until date 2, yielding

intact domestic firms for funds. Intact firms have

so they must borrow from foreigners

This they can do up to their

djjA.

w—

Unlike foreigners, domestics are

slack.

willing to lend to other domestic against their projects. Since firms

to borrow

up to Xak, we

refer to this quantity as

Denote the gross interest rate

out the

maximum

loan as long as

in this

A>

result of domestic

domestic

can use

this collateral

L 1 Then

the firm takes

collateral.

domestic loan market as

.

L\.

d\j

As a

at

they are to finance the distressed firms.

if

d j of financial

no output

=

Xak.

borrowing the firm raises -j^ for investment, to yield

-^ A

at date

2.

Combining the above transactions, and taking into account that date

investment

yielded ak at date 2, the profits accumulating to this firm at date 2 are,

Vd =

(w - d„,/)A

+

^A +

(1

-

X)ak.

Intact firms, on the other hand, have the opportunity to lend to distressed firms at date

1.

As long as Li >

1,

the intact firm will borrow up to

d\j

and invest these resources

in the

=w—

its

maximum

foreign debt capacity,

doj,

domestic loan market to yield Zq

value of date 2 claims that the intact firm purchases.

Then

.

Denote X\ as the face

the intact firm

profits of,

V =

i

xjLj

+Ak + {w- d 0J -

d hf )

=

(w - dQf )L l

+

Ak.

makes date

2

Finally, at date 0, firms are equally likely to

V5 ^ = max

- doj)(Li + A) +

hw

\^

2

1

k,d

j

(

A + (1 -

intact.

A)o

+

V

Thus they

solve,

^AJ/ k

i-i\

doj < w

s.t.

c{k)

The only market

be distressed or

=

do,f.

clearing condition

is

that the loans issued by distressed firms must

equal the loans purchased by intact ones:

~! dl,l

w

2

where the one half

in front of

1

= ^l,

(1)

each microeconomic decision reminds us that distressed and

intact firms form equally sized groups.

Definition. Equilibrium in the economy with only sequential spot loan markets consists

of decisions, (k,d j,dij,dii,x\)

and the domestic

interest rate, L\. Decisions are optimal

given Li, and given these decisions, the market clearing condition (1) holds.

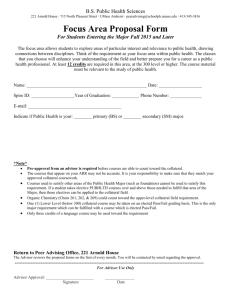

Figure

1

:

Date

1

Market Clearing

for

Domestic Loans

L

i

.

A

>v

•v.

//

/

1

X

/ ^^.

^

L

Increasing

-v

«*

-x

"•»

w-d

f

Domestic loans

.

Figure

1 illustrates

the market clearing.

On

the horizontal axis

the quantity of im-

is

ported goods lent by intact firms /borrowed by distressed firms. The vertical axis

of loans

L\. The supply

is

elastic at

L\

=

their international collateral constraint of

inelastic.

It is

for

Demand

for loans

line is

the middle solid line

1;

the lower dashed line

is

d\j

is

=w

—do,/, at which point

^£f

1.

,

which

the case where L\

is

downward

is

is

sufficient

lies strictly

small and as a result

sloping in L\.

alternatives

domestic collateral

between one and A;

demand

so collateral

is

constrained that intact firms have excess supply of funds and the interest rate

The parameter assumptions in Technical Assumption

L\

into the

A and one -

between

strictly

i.e.

market clearing condition

the solid

lies

is

ensure that equilibrium will have

1

line. In this case,

substituting date

,

—

1.

w-doj

Given

2. If

between these and foreign

=1

c'(k)^j— =

left

and

if

program can be written

this price, the first order condition for the date

where the

1

this is

w were large so that on the margin some

both w and Xak in their portfolio, then again

Alternatively,

domestic investor was holding claims against

hand

as:

&-

*

f

(3)

side represents the expected opportunity cost of the marginal units of

international collateral spent on setting

up a plant

at date 0, while the right

hand

side

the expected marginal revenue associated to the marginal plant.

Proposition

1

Consider two economies indexed by X and

•

A-Li(A)< A-Li(A');

•

Welfare

•

Date

is

s

2)

above the international interest rate of one. The reason for

would imply that L\

must be that L\

decisions

1~-

foreigners were willing to hold claims against Xak, then arbitrage

it

1

Xak

the asymmetry between domestic and foreign agents embedded in assumptions

assets

one.

gives,

Li =

Note that L\

completely

it is

The figure represents three

the case where there

the case where A

the price

to the point that the intact firms saturate

A > L\ >

easy to see from the figure that

A=

up

given by the curve,

is

demand: The highest dashed

that

1

is

increasing in X, so that

V sp°'(A) > V

s

A',

where X

>

A'.

p°*(A');

investment and borrowing are decreasing in X so that k sp? l (X)

Proof: Follows after a few steps of algebra, from

Then,

V spot

,

(2),

and

(3).

<

k spol (X').

is

The proposition

highlights the role of A

the market clearing condition

rises

in

1.

A

firm that decides to borrow

At date

which

1,

As A

prices.

increasing in A.

Thus

Fixing

as

A

of A. This has an important effect

less, is essentially

case, despite the fact that the resources yield

constrained.

0.

1

is

and

k,

from

rises,

L\

on date

"saving" these resources until

these resources are either used internally to yield A, or lent externally,

only internalizes L\ of this return.

date

welfare, decisions,

see that L\

toward the marginal product at date

decisions.

date

we can

on

rises,

to the borrower, the lender

Again, this occurs because the borrower

the spread between

A

and L\

This leads to greater investment at date

rises prices are less distorted

A

1

falls

is

collateral

causing firms to save more at

and welfare increases.

Essentially, as

A

by the credit constraint and the intertemporal savings decision

better reflects marginal products.

Public information of types and date

3

domestic insurance

markets

Our aim in this section is

to

insurance contract at date

l.

5

At

may seem odd

glance this

intuition

is,

may

because at date

way

1

under our spot market equilibrium,

into the

hands of the distressed

and

firms.

suggest that the ex-post allocation cannot be enhanced by further

reallocating domestic collateral to distressed firms since the scarcity

collateral,

of a domestic

that shu- es resources from intact to distressed firms at date

the international resources find their

all of

That

first

show that welfare can be improved through the use

this has already

been

fully transferred.

is

on international

However, in our setup, the welfare

gain from domestic insurance comes entirely from affecting the ex- post price of international

resources, Li, and bringing this closer to

decision of k

to set L\

=

is less

A,

Assumption

The shock

on

A

so that ex-ante the borrowing/investment

distorted. Moreover, reallocating ex-post wealth

affects

V — Vd

1

,

beyond what

is

needed

but not decisions, equilibrium, or ex-ante welfare.

3 (Public information)

at date

public information and insurance contracts can be written contingent

1 is

j.

Consider the following domestic insurance contract: All firms sign a grand insurance

contract at date

xo,i{d)

type-j.

=

>

xo,z

0.

with repayments in date 2 goods of

xqjl{j),

where xoj(i)

Since the types are observable, this contract can be

Repayments are enforceable

made

=

—xq,i

and

contingent on

as long as,

xq,i

<w — doj + Xak

Since there are an equal measure of each type, the insurance payments to distressed firms

are exactly funded by the receipts from the intact firms.

At date

1,

collateral of

its

an intact firm sees the domestic interest rate of L\

w - doj,

and an insurance

liability of xn,/-

>

1

and has international

Suppose that the firm lends

international collateral at L\, then its total resources are date 2 goods

(w - doj)L\

Against this

it

has the

liability of xo,(

1

^Recall that our focus

is

j)Li

of,

of,

+ Ak -xoj.

not on the possibility of more or

less

insurance from foreigners, rather

domestic arrangements given the limited access to international financial markets.

10

of

+ Ak

giving date 2 profits

V = {w-d

all

it

is

on

.

distressed firm borrows against its international collateral of

The

the proceeds in production to yield a date 2 return of A.

w-

and invests

do J

As long L\ < A,

it

borrows

d\j,

in the domestic debt market, satisfying the constraint that,

d\,i

Thus

it

makes date 2

we studied

(4)

a

in the

only loosens

d\j.,

little

[w -

more

do,/)

A+ A-

We know

closely.

previous section and that d\

without

is,

if

loss of generality

the inequality in (4) was

Li)-^ + Xak + x

(

dj

That

(4)

t

profits of,

Vd =

Consider

< Xak +xo i.

;

t

i

that

=

if xo,i

we can

then x

— 0, we

are back in the situation

Xak. Since increasing

i

can be reduced

until equality, while only

V

1

and

,

but

just,

l(w-d 0J )(A + L + ^(A+

V*"= max

1 )

S.t.

doj

<W

c(k)

=

x o,

Lemma

Vd

welfare (recall that agents are risk neutral). Given this, the date

not decisions or date

is

this point

.

loosening the insurance enforceability constraint and affecting the level of

problem

from

xo,;

set,

= Xak + xqi

strict,

,/

L\

i

a )k

+ l(A-L

Xak

X0

^

1)

1

'

do,/

<w — do,/ + Xak

2 In the insurance market equilibrium:

^=A

Proof:

We

can see this

firms will increase

xo,i

<w—

do,/

two

Suppose that

intact firms at date 1 have

(

fall for

Substituting

Lx —

xo,z

from the program, as long as

xo,j is

=

A >

L\,

the enforceability constraint that

= w — do,/ + Xak — 6,

with 6

>

0.

no international resources, and market clearing

loan market would require that L\

which x0) can

First,

steps.

Second, the only limit on

xo,/.

+ Xak.

in

A. As a comment, there

is

As

in

6

—*

0,

the

the domestic

a large interval within

this to hold.

A

into the

program

gives the

c'(fc)A

Contrasting this expression with the

first

=

first

^p.

order condition for investment,

(5)

order condition in the spot market equilibrium,

(3), implies:

11

Proposition 3 Let k ins

1.

and k 3? 01

be

the solution to (3).

Then:

//A-Zf'X),

k

S

2.

be the solution to (5)

If/S.—L i°

=

0,

spot

>

k

yins

md

ins

the two first order conditions coincide

>

yspot

and decisions as well

as welfare

are the same.

By

signing date

at date 1 until

it

insurance contracts firms bid

reaches A.

As a

result, firms

up

the price of international collateral

borrow

less at

date

leading to a better allocation of external resources across date

the insurance solution leaves no role for

A.

Indeed

by loosening the domestic

and date

1.

Note that

market

insurance market circumvents these

collateral constraint.

12

invest less, thus

this is the point. Since the loan

at date 1 is affected by collateral frictions, the date

frictions

and

4

We

Private information of types and planning solutions

A equal to one, as

shall henceforth set

importantly, from

now onwards we

plays a limited role in what follows.

it

acknowledge the many

shall

difficulties

More

encountered by

domestic insurance contracts in emerging economies and assume:

Assumption 4 (Private information)

The shock

at date

1 is

private information of the firm.

This assumption means that the insurance contracts of the previous section are not

possible since, at face value,

all

However the spot loan market

still

4.1

implement the

full

firms will prefer to claim to be distressed

is still

We now investigate

feasible.

and avoid payment.

whether

it is

possible to

insurance solution.

Mechanism design problem

We take a standard mechanism design approach. The types at date

and must be

1

are private information

by the mechanism. As usual, we appeal to the revelation principle to

elicited

focus on direct revelation mechanisms.

At date

Consider the following mechanism.

collateral to the planner.

The mechanism

0,

0,

of international

defined by,

is

m = {k,yi,yd ,Xi,xd

At date

w

agents hand over

).

the planner hands resources to create capital of k to each firm. At date

1,

agents

send a message of their type, j G {i,d}. They then receive an allocation of international

collateral (or

imported goods) of yj and a claim on date 2 domestically produced goods of

x3Thus the planner

solves the following problem:

V m = max

m

s.t.

-(Ak + yi +

2

c{k)<w

(RC1)

- {yi +

yd )

2

{ICC)

yi

,y d

(RCX)

xi

+

(DCC)

Xi,

(ICd)

+ -(ak + y d A+xd

2

{RCO)

(ICi)

Xi)

+ c(k)<w

>0

xd

<0

xd > —ak

Ak+y +Xi> Ak + y d +x d

ak + yd A +x d > ak + y A + x;

2

t

13

)

The

RCO and RC1

constraints are as follows:

on importing goods

for investment. Since agents

eral to the planner at date 0, the transfer to

can shu- e claims on date 2 goods

—

that this shu- ing does not create

new

maximum

are date

and date

hand over

all

them,

of their international collat-

must be non- negative. The planner

yj,

domestic collateral

i.e.,

—

The

last

On

DCC

requires

states that the

given by their domestic

is

it.

The asymmetry between Assumptions

and RCl.

RCX

1.

two constraints impose incentive compatibility so that

each type prefers the bundle intended for

To import goods

at date

collateral in the aggregate.

the planner can shu- e away from any of the agents

collateral constraint, ak.

resource constraints

1

and 2 are embedded

1

in

can be used - hence

for investment, only international collateral

the other hand, these goods can be shu- ed around

transferring claims against domestic collateral - hence

RCO, RCl and DCC.

DCC. We

among

RCO

domestics by

think this asymmetry

is

a distinguishing feature of an emerging economy. In a developed economy most assets are

both domestic and international

which case we could do away with

collateral, in

DCC

and

rewrite the RC's to include the domestic collateral of ak.

Given

convex,

linearity in y's

we

will

and

x's,

we

will arrive at corner solutions in

have an interior solution in

solution, rewrite the

xd

(xi

+ yi)

+

yd

xd

+ yd

+{A-l)y d >

xi

+ y +(A.-l)y

i

sum everywhere in

we were

compatibility constraint can

be slackened by lowering

yi

=

and

=

2(w -

c(k)),

and xd

an

=

be

at its

0,

yd

x,

and

yt

and increasing

us,

ak,x d

=

gives,

771

first

on

highest value and x d to be at

V = max -(,4 +

k

yi

— 2(w - c(k)),Xi =

and rewriting the optimization problem

.

a) A;

+ A{w -

2

order condition to the planning problem

c'{k)A

is

= A+

2

14

then the incentive

£j.

Thus consider

Applying the same argument to (x d

-ak. Combining, gives

m= (k,yi —

The

interior point

Xi at its highest value.

dictates a solution of y d to

yd

at

i

the program except in this last incentive

compatibility constraint. If

the solution of

as,

+ Vi >

appears as a

is

In order to see which corners determine the

two incentive compatibility constraints

Xi

Note that

k.

them. Since c(k)

a

c{k)).

-ak).

its lowest.

+ yd

)

Thus,

Let k* be the solution. The

last step is to verify that

compatibility constraints. That

the solution

satisfies

the incentive

is,

A(j/d

- Vi) >Xi-x d

>yd -yi

or,

A(w-c(k*))>

ak*

>w-c{k*)

which can be shown to hold under Technical Assumption

1.

Proposition 4 The optimal mechanism under private information of types implements

full- insurance public

the

information solution.

This follows directly from comparing the

first

order conditions in this solution and the

insurance solution of the previous section.

The mechanism works because

it

between distressed and intact firms.

receives

exploits the differential valuation of imported goods

If

a firm claims to be distressed rather than intact

2{w — c(k*)) imported goods, but forgoes 2ak* claims on date 2 goods. The

rate implicit in this choice

where the technical assumption ensures

w - c(k*)

that A > L\ >

borrow at L\ and

intact ones lend at L\.

insurance solution

is

We now

'

A, while the intact firm values

at

Both

it

at one.

Thus

distressed firms effectively

is

enhanced, and the

full-

achieved.

— to act

Domestic credit

first

distressed firm values the

6

turn to the implementation of the planning solution and consider three sets of

private consortium

The

A

l.

types' welfare

alternatives, noting that each requires the planner

4.2

interest

is,

1

imported goods

it

solution

—which in some

instances could be a

(and hence be able to monitor) on a different margin.

lines

we consider

is

a credit-line/banking arrangement akin to Diamond and

Dybvig's (1983) deposit contracts in the context of consumption insurance.

Suppose that

all

firms

hand over

w — c(k*)

to the

bank

at date 0.

with c(k*) for the purpose of building a plant. The bank then

withdraw

6

w - c(k*)

Also note that L\

<

at date

1

L\ since k"

as well as a credit line to

<

k.

15

offers

This leaves each firm

each firm the right to

borrow an additional

w-

c(k*) at

.

the interest rate of L\. Funds not withdrawn at date

date

2.

1

earn the interest rate of L\ until

7

At date

1,

bank and withdraw

distressed firms return to the

w-

In addition,

c(k*).

they choose to take out a further loan against domestic collateral of ak* at the rate of L\.

This gives them imported goods of exactly 2(w

-

c(k*))

which they invest

date 2 at

until

the private return of A.

Since intact firms' alternative use of imported goods returns only one, intact firms choose

not to withdraw their funds at date

return of L*(w

-

c(k*))

=

1

and instead wait

until date 2 providing

to

make any

it

That

side trades.

is

first

pointed

requires the fairly strong restriction that agents not be allowed

is,

all

firms must

be

the bank and be barred from trading in a market.

arrangement

total

ak*

This structure clearly implements the planner's solution. However as was

out by Jacklin (1985)

them a

If

restricted to exclusively trade with

we drop

banking

this restriction, the

no longer coalition incentive compatible and the allocation reverts to the

competitive equilibrium. 8

In our context, Jacklin's critique can be formulated as follows. Suppose that one firm

chooses to opt out of the banking arrangement, and privately makes an investment decision

of k.

At date

1,

the firm

is

either distressed or intact.

suppose that

If distressed,

it

approaches a firm within the banking arrangement and offers to borrow at the interest rate

of L{ against domestic collateral of ak.

Since this return

banking arrangement, the firm withdraws some of

to the rogue firm.

The return

to the rogue firm

Vd = A(w while the firm in the banking arrangement

offers to lend to a firm in

its

as good as the return in the

international collateral

and

offers

it

is,

c(k))

+ 77 A,

unaffected.

is

is

If

the firm

is

intact,

it

instead

the banking arrangement at the interest rate of L*. Once again,

the banking firm accepts, and the rogue firm's profits are,

V*

Combining these

last

=

L\{w -

c{k))

two expressions gives us the date

V T °9^{L\) = max -(u; - c(k))(A +

k

7

L\

We

is left

L\)

program

in

free to adjust in the out-of-equilibria event that

of,

+ - ( A77 + a)

2 \

2.

do not impose a sequential service constraint as

Thus there

+ Ak

Li-y

k.

I

Diamond and Dybvig

(1983). which

more than half of the firms decide

no "bank-run" equilibrium.

8

Thc result that competitive spot markets may undermine insurance arrangements

means that

to

withdraw.

is

See for example. Rothschild and

Stiglitz(1976). Atkeson

16

and Lucas (1992), or

Bisin

arises in

many

settings.

and Rampini (2000).

The

first

order condition for this program

+ Ll)=J2 +

c'(k)(A

Comparing

< A

L\

is,

planning problem, we can see that

this to the first order condition of the

>

the rogue firm makes a choice of k

A.

k* and attains strictly higher utility

participated in the banking arrangement. Given this, the banking arrangement

if it

for

than

would

unravel.

We

can take this to

its

end by explicitly accounting

logical

trades in the planning problem. This

is

for the possibility of side

done by adding a constraint

that,

ym > yrogue^

Now

the objective in the planning problem

Vm =

=

Substituting in L\

w

^

k .\

,

this

is,

can be rewritten

V™=±(w-c(k*))(A +

Note that

this

objectives in

with the

is

V™

the same as the expression

and

maximum

in

in

VTOgue

yr °9 ue

+ ha + A).

{w - c(k*))A

+ ±(Af; + A)k*.

Ll)

for

as,

V r°9ve

if

evaluated at k

=

weakly exceeding that of

1

is

_

=

to choose k*

Vm

k

.

r °9ve

Given

this,

Since both

maximum,

we can conclude

so that,

ak rogve

w- c(k °9ue

r

)'

These are the same optimality and market clearing conditions that arose

2.2.

.

are strictly concave, they each have a unique

that the best that the planner can do

markets of section

k*

in the spot loan

In summary,

Proposition 5

(a)

The

ner can

credit-line

arrangement implements the full-insurance solution as long as the plan-

restrict agents

restriction,

from making side

the credit-line

trades,

arrangement collapses

loan markets.

17

(b)

to

In the absence of

this exclusivity

the competitive equilibrium with spot

.

Capital inflow taxation/Liquidity requirement

4.3

Let us consider next a tax/ transfer scheme based on date

borrowing (or investment of

Since the primitive problem in the spot loan market equilibrium

k).

borrow /over-invest at date

The planner taxes

proceeds (T) in a

all

0,

that agents over-

a tax has the potential of achieving the optimal solution.

external borrowing at the rate of r and redistributes the

date

lumpsum

is

fashion at date

0,

T = rdoj = rc(k*)

The program

a firm

for

h

wI

max

k

This gives the

first

is,

c (k)-Tc(k)+T)(L 1

+A) + ^ (A + A-^-)k.

2 \

L\ J

order condition,

c'(A:)(l

+

+ A) = (a + Aj-]

t){L x

Thus,

1+T=

2A

^4+f"

LL-

A + Li A + a

where,

U = L\.

It is

straightforward to verify that for L\

An

< A,

alternative, but similar in spirit, implementation of the borrowing tax

-

d oj

of

all

an interna-

foreign borrowings be retained as a liquidity requirement for one-period

until a crisis arises).

Then, since firms choose to borrow c^ j,

saving exactly the right amount until date

While unlike the credit

market

is

suppose that the planner insisted that a fraction,

tional liquidity requirement. For example,

JU

the optimal tax will be positive.

for loans,

line

this

(i.e.,

arrangement has them

1

arrangement each of these solutions can co-exist with the

they do require that the planner observe

all

external borrowings. If agents

could evade the tax/return scheme or liquidity requirement, and trade in the loan market

at date 1,

they would prefer

planner's control since L\

Finally,

date

it

is

to.

Moreover, this incentive

rises

as

more

firms

fall

under the

falls.

worth pointing out that

and then remove the tax

at date

this

1.

If

arrangement requires the planner to tax at

the tax

is left

active for

both periods, the

equilibrium would be exactly as in section 2.2, with the exception that the interest rate on

international collateral would rise to

1

+

t.

In general, this will lead to a worse

than the case of no-taxation.

18

outcome

Proposition 6

planner can observe

// the

external borrowings, a borrowing tax or

all

liq-

implements the full-insurance solution.

uidity requirement

Capital inflow sterilization

4.4

Consider a government that issues b face value of two period bonds at date

Thus the

international reserves of £-.

on these bonds

interest rate

is

L

,

in return for

and

in order to

purchase these bonds, firms increase their external borrowings by -jK

At date

using

the government simply buys the bonds plus claims against domestic collateral

international reserves of ^-. Finally, at date

its

taxes of

1,

T in order to balance its budget.

at the interest rate of 1^, the

2,

the government raises

Since the investment of reserves at date

budget constraint

for

the government

lumpsum

1 is

done

is,

^-L 1 + T=b,

where we note that

L =

if

Li, budget balance

is

achieved without having to raise taxes.

There are two assumptions we make on the government.

tax

liabilities are rationally

Thus the

anticipated

collateral of each firm is

First,

and constitute a reduction

we assume that future

in seizable

endowments.

reduced by T, so that, for example, the domestic loan

capacity becomes,

d\,d

<w-\-ak —

Second,

we assume that the government bonds that

That

they are

is

like

T

are sold are only domestic collateral.

ak and hence foreigners do not purchase these bonds.

In this context, suppose a firm purchases b

bonds

at date 0.

Then

its

program can be

written as,

max

„,

1,

—(w

k,b

2

s.t.

c(k)

Market clearing

c(k)

+

-

b

WT

-r-)(Li

1 /\,

AX

m

+ A) + \ ( Ak + b - T +

,

—A

(ak

+ b - T))

—

<w

La

is,

L\

—

ak

+b-T

There are two cases to consider, depending on whether or not the international borrowing

constraint

9

is

slack or not. Consider first the case that, c(k)

+ £- <

w. Since firms are at

See the appendix in Caballero and Krishnamurthy (2000b) for a model justifying this assumption

terms of a risk of suspension of convertibility.

19

in

an

interior in their purchase of bonds,

must be that Lq

it

—

and therefore

L\,

T =

0.

Substituting this back into the market clearing condition:

—) =

L 1 (w — c(k) +

ak

+b

ak

w—

c(k)

In other words, intervention has no effect in this case.

The other case

sells

where the international constraint binds. Suppose that the government

is

enough bonds so that

As always, the

RHS

c(k*)

+

-^

—

L\ at date

optimahty

Since d{k*)

= "4^°, we

< A, we have that

exactly c(k*)

left,

is

the opportunity cost

d(k*)(L{+A)

Ll

at Lq, sold

Given the intervention,

on these bonds

be,

-

arrive to,

Lo

is

either L\ or A.

for the private sector requires that the interest rate

L° =

For L\

The LHS

be invested in the government bonds

and the proceeds reinvested at

1,

order condition for the private sector

first

the return from an extra unit of k.

is

of these resources. d{k) could otherwise

at

w. The

Lq

>

~

A + ^a 2A

A + a A + Lt Lv

L\. Since after purchasing these bonds the private sector has

amount of

firms invest the optimal

k*

,

and the full-information solution

achieved.

Essentially, the implementation has the

bond with an

interest rate exceeding L\.

investment. However,

On

requires

It

10

endowments,

On

borrowing or

does require that the government be able to tax and issue bonds.

first

power

this tax

the other hand,

arrangement we

it

discussed,

is

not any stronger than what we gave the private

does come with a buried assumption. As in the banking

if

agents had the option to not pay taxes, not buy govern-

ment bonds, but be allowed to trade with the

this option.

10

no knowledge of date

the one hand, since we have assumed that taxes come out of otherwise privately

seizable

sector.

it

government "subsidizing" savings by offering a

As

in the

firms

banking arrangement, the

are paying taxes, they would prefer

sterilization policy

See Holmstrom and Tirole (1998) or Woodford (1990)

20

who

for

is

the converse case.

not coalition incentive

compatible. However,

it

seems reasonable

to believe that coalition incentive compatibility

with respect to taxes

is

easier to achieve

than that of ruling out side trades in a private

banking arrangement.

We

label this policy as sterilization because, in practice,

emerging markets that

sterilize

accumulate international reserves on the one hand, and issue government bonds on the

other.

policy.

However our bond policy

is

"real"

and may seem closer

In Caballero and Krishnamurthy (2001b)

"real" side of a sterilization policy sheds light

only the standard, purely monetary, side of

Proposition 7

we have argued

than to monetary

that emphasizing this

on observed outcomes that are puzzling when

it is

considered.

Sterilizing capital inflows at date

and consequently reversing

to fiscal

by issuing two period

government bonds,

the transaction at date 1, achieves the full-insurance solution as

long as the planner has the power to tax endowments

tional collateral by foreign investors.

21

and bonds are not viewed as interna-

Final

5

As

Remarks

our previous papers, we have synthesized emerging markets'

in

terms of

volatility in

two basic ingredients: weak links with international financial markets and underdeveloped

domestic financial markets. The need for external insurance stems from the former

ciency, while the latter is

The contribution

insuffi-

behind the external underinsurance problem.

of this paper

is

twofold: First,

we have

explicitly

modeled the

infor-

mational constraint on domestic insurance markets and have thereby been able to discuss

the feasibility of contractual arrangements to solve the underinsurance problem.

we have explored

in a unified setting several of the

main

Second,

management

international liquidity

strategies available to these countries.

If

domestics can write complete insurance markets with each other, external underin-

surance disappears. However the mechanism behind this result

channel.

The main problem

allocation of

its

of the

its

not a standard insurance

economy during a sudden stop

limited international collateral but

Domestic insurance improves

is

efficiency

is

not in the domestic

on the aggregate amount

by aligning the price of international

of the latter.

collateral

marginal product. In this sense, domestic insurance relates to our discussion

and Krishnamurthy (2001c) of the incentive

of a countercyclical

monetary policy

in

in

with

Caballero

— as opposed to the standard liquidity— virtues

economies subject to sudden stops. In

there

fact,

we

argue further that such policy could in some instances substitute for the absence of domestic

insurance.

If

that

domestic insurance

it

is

not possible -

when types

are unobservable -

we showed

was possible to design mechanisms that could attain the same aggregate outcomes

and welfare of the

however,

practice

is

full

information case.

their failure to

meet a

The common

Achilles' heel of these solutions,

coalition incentive compatibility constraint;

which

means that they may not be robust to the existence of secondary markets

to opt out of the mechanism.

that bond-policy

is

Among

the solutions of these type

we

studied,

or

in

ways

we argued

probably more robust than the others, but this policy can also have

potentially large drawbacks

illiquid

i.e

if

the intervention

secondary markets during

crises (see

is

not large enough and public bonds have

Caballero and Krishnamurthy (2001b)).

22

References

[1]

Atkeson, A. and

RE.

Lucas,

Review of Economic Studies

[2]

Efficient Distribution with Private Information,"

59, July 1992, pp. 427-453.

and A. Rampini, "Exclusive Contracts and the

Bisin, A.

mimeo Northwestern

[3]

"On

Jr.,

University, 2000.

C, M. Eichenbaum, and

Burnside,

Institution of Bankruptcy,"

Rebelo, "Hedging and Financial Fragility in

S.

Fixed Exchange Rate Regimes," mimeo Northwestern University, 1999.

[4]

Caballero,

RJ. and A. Krishnamurthy,

straints in a

Model

of

"International

Emerging Market

and Domestic Collateral Con-

Crises," forthcoming in Journal of

Monetary

On

the Risks

Economics, 2001a.

[5]

Caballero, R.J. and A. Krishnamurthy, "International Liquidity Illusion:

of Sterilization,"

[6]

Caballero,

NBERVVP #

8141, 2001b.

RJ. and A. Krishnamurthy, "A

Fear of Floating and Ex-ante Problems,"

[7]

Caballero,

RJ. and A. Krishnamurthy,

Vertical Analysis of Crises

mimeo May

[8]

NBER WP #

NBER WP #

Underinsurance

7792, July 2000a.

Caballero, R.J. and A. Krishnamurthy, "International Liquidity

ization Policy in Illiquid Financial Markets,"

[9]

2001c.

"Dollarization of Liabilities:

and Domestic Financial Underdevelopment,"

and Intervention:

Management:

Steril-

7740, June 2000b.

Diamond, D. W. and P.H. Dybvig, "Bank Runs, Deposit Insurance, and

Liquidity,"

Journal of Political Economy 91, 1983, pp. 401-419.

[10]

Dooley, M., "Responses to Volatile Capital Flows: Controls, Asset-Liability Manage-

ment and Architecture," World Bank Conference on Capital Flows, Financial Crises

and

[11]

Policies, April 1999.

Holmstrom, B. and

Political

[12]

Economy

Jacklin, C.J.,

tractual

J. Tirole,

"Private and Public Supply of Liquidity," Journal of

106-1, February 1998, pp. 1-40.

"Demand

Deposits, Trading Restrictions and Risk Sharing," in Con-

Arrangements for Intertemporal Trade, edited by E.Prescott and N.Wallace.

Minneapolis. U. of Minnesota Press, 1987.

[13]

Krugman,

P.,

"What Happened

to Asia?"

23

MIT mimeo,

1998.

[14]

Rothschild,

M. and

J.E. Stiglitz, "

Equlibrium in Competitive Insurance Markets:

An

Essay in the Economics of Imperfect Information," Quarterly Journal of Economics

80,

[15]

pp 629-49.

Woodford, M. "Public Debt as Private Liquidity," American Economic Review, Papers

and Proceedings 80 May

1990, pp. 382-88.

24

6

1*

5

Date Due

Lib-26-67

MIT LIBRARIES

3 9080 02246 0619