Document 11163345

advertisement

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011 with funding from

Boston Library Consortium IVIember Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/formofpropertyriOOacem

-^pr)

.

("b

B31

^415

3^1

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Department of Economics

Working Paper Series

The Form of Property Rights: Oligarchic

Democratic Societies

vs.

Daron Acemoglu

Working Paper 03-34

September 28, 2003

Room

E52-251

50 Memorial Drive

Cambridge, MA 02142

This

paper can be downloaded without charge from the

Social Science Research Network Paper Collection at

http://ssrn.com/abstract=457724

BBWi

fv/IASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE

OF TECHNOLOGY

The Form

of Property Rights: Ohgarchic vs.

Democratic Societies*

Daron Acemoglu

Department of Economics

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

MA 02142

Cambridge,

September

28,

2003

Abstract

This paper develops a model where there

property rights of different groups.

An

a trade-off between the enforcement of the

is

"oligarchic" society,

hands of major producers, protects their property

rights,

where

political

power

is

in the

but also tends to erect significant

entry barriers, violating the property rights of future producers. Democracy, where poUtical

power

is

more widely

to avoid entry barriers.

diffused,

When

imposes redistributive taxes on the producers, but tends

taxes in democracy are high and the distortions caused

by entry barriers are low, an ohgarchic society achieves greater efficiency. Nevertheless,

because comparative advantage in entreprenemship shifts away from the inciunbents, the

inefficiency created by entry barriers in oligarchy deteriorates over time. The typical

pattern is therefore one of the rise and decline of oligarchic societies: of two otherwise

identical societies, the one with an oligarchic organization wiU ffist become richer, but

later fall behind the democratic society. I also discuss how democratic societies may be

better able to take advantage of new technologies, and how the unequal distribution of

income in an oligarchic society supports the oligarchic institutions and may keep them in

place even when they become significantly costly to society.

Keywords: democracy, economic growth,

entry barriers, oligarchy, pohtical economy,

redistribution, sclerosis.

JEL

Classification: P16, OlO.

thank Robert Barro, Olivier Blanchard, Simon Johnson, James Robinson, and participants at

NBER Summer Institute and Harvard

University macro seminar for useful comments, and Miriam Bruhn and Alexander Debs for excellent

*I

the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research conference, the

research assistance.

Introduction

1

There

is

now

a growing consensus that institutions protecting the property rights of pro-

ducers are essential for successful long-run economic performance.^ There

is

no agreement,

however, on what constitutes "protecting the property rights of producers" or on the costs

and benefits of various

where

society

different "forms of property rights".

political

power

is

in the

One possibility

hands of the economic

elite, for

is

an

oligarchic

example, the ma-

jor producers/investors in the economy. This type of organization not only ensures that

major producers do not

enables

them

fear expropriation or high rates of taxation,

to create a non-level playing field

and a monopoly position

in essence violating the property rights of futiue potential producers

from taking advantage of

more

profit opportunities).

but also typically

The

alternative

uted, thus effectively in the hands of poorer agents

who can

excluding

democracy

is

appropriately, popuhst democracy), where political power

(i.e.,

for themselves,

is

them

(or

perhaps

more equally

distrib-

use their power to tax the

producers' profits.^ But in return, incmnbent producers will be unable to create

signifi-

cant entry barriers against entrants, ensuring better property rights for future potential

producers.'^

This paper constructs a simple model to analyze the trade-off between oligarchic and

democratic

riers.

The model

societies.

features

two pohcy

distortions: taxation

and entry bar-

Taxes, which redistribute income from entrepreneurs to workers, are distortionary

because they discourage entrepreneurial investment. Entry barriers, which redistribute

income towards the entrepreneurs by reducing labor demand and depressing wages,

tort the allocation of resources because

dis-

they prevent the entry of more productive agents

into entrepreneurship.^

^See,

among

others, the general discussions in Jones (1981),

empirical evidence in

De Long and

Shleifer (1993),

North (1981), and Olson (1982), and the

(1995), Barro (1999), Hall and

Knack and Keefer

Jones (1999), and Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson (2001, 2002).

^Although there is a close connection between dictatorship and oligarchy, some electoral democracies

may be

"oligarchic" according to the definition here, because the economic elite controls the parties or

the electoral agenda.

Mobutu, a highly predatory state, controlled either by an

incumbent and future producers.

The focus here is not these cases, but the trade-offs between distortionary redistributive taxation and

entry barriers. A full taxonomy of regimes would distinguish predatory regimes from oligarchic and

•^In

certain societies such as in Zaire under

individual or the political

elite,

may

violate the property rights of both

democratic regimes.

*

Entry barriers

may

take the form of direct regulation, or of policies that reduce the costs of inputs,

especially of capital, for the incumbents, while raising

them

for potential rivals.

to the chaebol appear to have been a major entry barrier for

new

Cheap loans and subsidies

Korea (see, for example,

firms in South

Kang, 2002). See also La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer (2003) on the implications of government

ownership of banks, which often enables incumbents to receive subsidized credit, thus creating entry

The

trade-off between these

two

different types of distortions determines

more

and generates greater aggregate output.

ohgarchic or a democratic society

is

OUgarchy avoids the disincentive

effects of taxation,

duced by entry

barriers.

create a

more

are high

and the

efficient

Democracy imposes higher

When

level playing field. ^

distortions caused

but

suffers

from the distortions

intro-

redistributive taxes, but also tends to

the taxes that a democratic society will impose

by entry

barriers are low, oligarchy achieves greater

and generates higher output; when democratic taxes are

efficiency

whether an

relatively

low and en-

try barriers create significant misallocation of resources, a democratic society achieves

greater aggregate output.

In addition, a democratic society typically generates a

equal distribution of income than an ohgarchic society, because

from entrepreneurs to workers, while an

it

redistributes

more

income

oligarchic society adopts policies that reduce

labor demand, depress wages and increase the profits of incumbents.

More

interesting are the

dynamic

trade-offs

between these poHtical regimes.

Initially,

entrepreneurs wiU tend to be those with greater productivity, so an oligarchic society

generates only hmited distortions. However, as long as comparative advantage in entre-

preneurship changes over time,

will eventually shift

it

away from the incumbents, and the

entry barriers erected in ohgarchy will become increasingly costly to efficiency.

therefore one where, of two otherwise identical societies, the oligarchy will

pattern

is

become

richer,

but later

fall

distortions,

also

democracy

is

behind the democratic

some parameter

gests that, at least under

I

A typical

The model

therefore sug-

configurations, despite its potential economic

better for long-run economic performance than the alternatives.

show that democracies may be

than oligarchic

society.

first

societies.

This

is

able to take better advantage of

new technologies

because democracy allows agents with comparative

advantage in new technology to enter entrepreneurship, while oligarchy typically blocks

new

entry.

The above

in particular

discussion takes the pohtical regime

whether the society

research in political

economy

barriers for potential entrants.

An

is

is

and the distribution of political power,

ohgarchic or democratic, as given.

A

major area of

the determination of equihbrium political institutions.

interesting case in this context

is

Mexico at the end of the nineteenth

century, where the rich ehte controlled a highly concentrated banking system, protected by entry barriers,

and the resulting lack of loans for new entrants enabled the elite to maintain a monopoly position in other

Haber (1991, 2002).

^This argument does not deny the presence of entry barriers in democratic societies, for example in

much of Western Europe, but suggests that the role of entry barriers in these instances may be to create

rents to a specific group of workers rather than protecting incumbent firms (on cross-country patterns of

labor regulation, see Djankov, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer, 2003).

sectors. See

When

should we expect a society to become oligarchic and remain so even

becomes increasingly costly?

I

when

this

analyze this question by embedding the basic setup in a

simple (and reduced-form) model of regime change where groups with greater economic

power are

also

more

likely to prevail politically. Social

groups that become substantially

richer in a given political regime

may be

protect their privileged position.

In oligarchy, incumbents have the poUtical power to

erect entry barriers to raise their profits.

able to successfully sustain that regime

These greater

and

profits, in turn, increase their

pohtical power, making a switch from oligarchy to democracy

more

difficult,

even

when

entry barriers become significantly costly.

Although the model economy analyzed in

this

paper

is

highly abstract,

sheds light on a nimiber of interesting questions.

The

economic performance of democratic and ohgarchic

societies.

ples of

both democratic and ohgarchic

societies that

growth. For example, the United States and

much

first set

of issues

it

is

nonetheless

the relative

In practice, there are exam-

have achieved high rates of economic

of

Western Europe during the postwar

era illustrate the potential economic success of democratic societies. In contrast,

Japan

both in the prewar and the postwar periods, and South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore in

the postwar era are examples of ohgarchic societies that have pursued pro-business pohcies

and achieved successful economic performance.^ The development experiences of Brazil

and Mexico, on the other hand,

illustrate

both the potential gains and

oUgarchic regimes. Haber (2003), for example, explains

how

significant costs of

import-substitution pohcies

in these coimtries were adopted to protect the businesses of the rich ehte

the government.^

He

further documents

how

aHgned with

these import-substitution policies enabled

®A11 four countries approximate oligarchic societies. For example, in Japan, the pre-war era is commonly recognized as highly oligarchic, with the conglomerates known as the zaibatsu dominating both

politics and the economy (the title of the book on pre-war Japanese politics by Ramseyer and Rosenbluth,

1995, is Politics of Oligarchy). The postwar politics in Japan, on the other hand, have been dominated

by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which is closely connected to the business elite (see, for example,

Ramseyer and Rosenbluth, 1997, and Jansen, 2000). In the Korean case, the close links between the large

family-run conglomerates, the chaebol., and the politicians are well-documented (see, for example, Kang,

2002). In both cases, government policy has been favorable to major producers and provided them with

subsidized loans and protected internal markets as well as secure property rights (e.g., Johnson, 1982,

Evans, 1995). For example, in Japan, the Antimonopoly Act of 1947 imposed by the Americans was

soon relaxed, and the LDP introduced various anticompetitive statutes to protect existing businesses.

Ramseyer and Rosenbluth report that in 1980 there were 491 cartels, and "almost half [of those] had been

in effect for twenty-five years and over two-thirds for more than twenty years" (1997, p. 132). However,

it should also be noted that inequality of income in both cases has been limited, most likely because of

other historical reasons, for example, the extensive land reforms in South Korea undertaken to defuse

rural unrest fanned by the Communist regime in the North (e.g., Haggard, 1990).

^For example, he describes the formulation of policies in early 20th-century Mexico as "Manufacturers

who were

part of the political coalition that supported the dictator Porfirio Diaz were granted protection,

War

rapid industrialization both before and after World

Beyond these

sMps

but also created significant

and economic problems.

distortions

show that

II,

in the

selective examples, cross-coimtry empirical analyses, e.g.,

postwar

era, electoral

Barro (1999),

democracies have not grown faster than dictator-

(wliich generally correspond to oligarchic societies in

terms of the model), despite the

weU-documented presence of disastrous dictatorships with very weak records of property

rights enforcement.

and oUgarchic

The model

is

consistent with this pattern, because both democratic

societies create distortions.

from democracies that are

Successful economic performances will

relatively less redistributive,

and from ohgarchic

societies

come

where

entry barriers are hmited or where heterogeneity of productivity in entrepreneurship

is

relatively imimportant.

Existing evidence

also consistent with the notion that democracies are

is

tributive, but introduce fewer entry barriers

(2002, Table 7)

cies.

show that there

than

more entry

are

oligarchies. For

more

redis-

example, Djankov et

barriers in non-democracies

al.

than democra-

Rodrik (1999) shows that labor share and wages are typically higher in democracies

than in dictatorships. Democracies also appear to tax more than non-democratic countries.

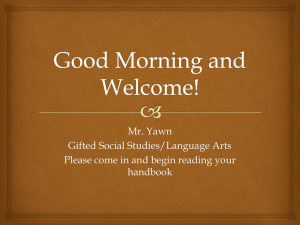

Figure

against the

1

shows a

significant positive correlation

Freedom House measure

of democracy, once the effect of log

has been taken out from both variables.

is

between tax revenue over

Appendix

B

GDP

GDP

per capita

demonstrates that this pattern

robust to controlling for education, population, continent dummies, and to excluding

former communist countries and federal countries.^

The second

set of questions that the

and dechne of nations.

A common

model might shed some Mght on

conjecture in social sciences

also lays the seeds of futme failures (e.g.,

is

relate to the rise

that economic success

Kennedy, 1987, Olson, 1982). The analysis in this

paper suggests a specific mechanism formalizing this conjecture: early success might often

come from providing

prevent entry by

security to

new groups,

major producers, who then use

creating d3mamic distortions. This

by the contrast between the economic

their political

mechanism

histories of the Northeastern

is

power to

illustrated

United States and the

Caribbean diuing the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries.

everyone else was out in the cold"

(p.

18),

and during the

later era, "manufacturers could

lobby the

executive branch of government, which could then, without the need to seek legislative approval, restrict

the importation of competing products"

(p. 48).

^Moreover, at least part of the economic problems of some democracies also seem to stem from "antibusiness" policies. See, for example, Besley and Burgess (2003) for an interesting analysis of the economic

costs of pro-labor regulation in India.

ST

o

IN

HRV

_

LSO

Q

o

BEL

o

£

O

itaS'^'^

''f^jADfPOL

.

KEN

WS^^^^"^^

U)

5

c

BtpflHA

-

cP^

'^^^^wUgXij.....-------^

Q)

a.

£

o

o

-

mnGoj^„^

L;bG-TUB--roBRA<DEii'p

__——-^

o_

^AN

SDN

§m

1

mn

'^'94iV

^'"'•arg

CO

1

2

'(/)

-

o

BHR

-

c\j

1

q:

KWT

ARE

-5-4-3-2-101234

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

5

Residuals from Democracy Index

Figure

Residuals of tax revenues as a percentage of

1:

Freedom House democracy index

in 1997-98.

corresponding variables on log

The Northeastern United

GDP

Both

GDP

in 1998 vs. residuals of

residuals are from a regression of the

per capita in 1998. See Appendix B.

States developed as a typical settler colony, approximating

a democratic society with significant

political

power in the hands of smallholders

(e.g.,

Galenson, 1996).^ In contrast, the Caribbean colonies were clear examples of oUgarchic

with pohtical power in the monopoly of plantation owners, and few rights for the

societies,

slaves that

made up

the majority of the population

1972). In both the 17th

places in the world,

United States

1995,

and 18th

centuries, the

(see, e.g.,

Caribbean

Beckford, 1972, and Dunn,

societies

were among the richest

and almost certainly richer and more productive than the Northeastern

(see, e.g.,

Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson, 2002, Coatsworth, 1993,

Engerman, 1981, and Engerman and

Sokoloff, 1997).

Eltis,

Although the wealth of the

Caribbean undoubtedly owed much to the world value of its main produce, sugar,

it

seems

that Caribbean societies were able to achieve these levels of productivity because the

planters

had every incentive to

But starting

^This

is

invest in the production, processing

in the late 18th century, the

and export of sugar.

Caribbean economies lagged behind the United

a relative statement, not meant to deny the significant power of rich industrialists and landown-

ers in the 19th-century United States (see, e.g., Beard, 1952).

States

and many other more democratic

opportunities, particularly in industry

Engerman and

2002, and

societies,

and commerce (Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson,

Sokoloff, 1997).

and Western Eiu"ope invested

While new entrepreneurs

in these areas,

hands of the planters, who had no

which took advantage of new investment

power

in the

in the United States

Caribbean remained in the

interest in encoTiraging entry

by new groups. ^° Though

not as stark as the contrast between the Northeastern United States and the Caribbean,

the experiences of other ohgarchic societies, including those of Japan, South Korea, Brazil,

and Mexico, where

initial

growth supported by close relations between major producers

and the government has shown a tendency to come

to

an end, are also consistent with

the mechanism emphasized in this paper.

Many

studies

on economic growth and the pohtical economy

of development have

pointed out the costs of entry barriers, while others have emphasized the disincentive

effects of redistributive taxation.

fully articulates

For example, the classic by North and

Thomas

force-

the view that monopoly arrangements are the most important barrier

many

to growth,

and

joint stock

company, replacing the old regulated company" and "the decay of industrial

cite "the

ehmination of

of the remnants of feudal servitude,..., the

regulation and the declining power of guilds" as key foundations for the Industrial Revolution in Britain (1973, p.

155).

This point of view

is

also developed in Parente

and

Prescott (1999), and in the recent book by Raj an and Zingales, where they emphasize the

threat to successful capitahsm from the "incumbents, those

who

Ushed position in the marketplace and would prefer to see

remain exclusive." (2003,

18).

An

even larger

For example,

Romer

Tabellini (1994),

literature,

it

already have an estab-

on the other hand, focuses on the cost of

(1975), Roberts (1977), Meltzer

p.

redistribution.

and Richard (1981), Persson and

and Alesina and Rodrik (1994) aU construct models

in

which the median

voter chooses high levels of redistributive taxation, distorting saving, investment or labor

supply decisions (see also Benabou, 2000, on how, imder certain circumstances, democracy

may

not generate enough redistribution). Barro succinctly summarizes the costs of

a democratic regime as

"...the

tendency to enact rich-to-poor redistribution of income

(including land reforms) in systems of majority voting and the possibly enhanced role of

interest

groups in systems with representative legislatures." (1999,

am not

aware of any analysis that relates the distortions created by redistributive democ-

p. 49). Nevertheless, I

racy and those caused by entry barriers in oligarchy as the two sides of the trade-off over

^"Sokoloff

and Kahn (1990) and Kahn and Sokoloff (1993) show that many of the major U.S. inventors

were not members of the aheady-estabhshed economic ehte, but new comers with

in the 19th century

diverse backgrounds.

the "form of property rights", nor any analysis of the dynamic costs of oligarchy.

Other closely related papers include Krusell and Rios-Rull (1996), Acemoglu, Aghion

and

Zilibotti (2003), Learner (1998), Robiioson

and Vollrath

(2003).

The

and Nugent (2001), and Galor, Moav

result of potential cycles in oligarchy in the current

model

is

related to the political-economic cycles in Krusell and Rios-Rull (1994). In their model,

technology-specific investments create vested interests opposed to the introduction of new

technologies.

The pohtical power

of these vested interests

may lead

to growth cycles. Ace-

moglu, Aghion and Zilibotti (2003) develop a theory where protecting large firms at the

early stages of development

is

beneficial because

it

relaxes potential credit constraints,

but such protection becomes progressively more costly as the economy approaches the

world technology frontier and selecting the right entrepreneurs becomes more important.

That paper

also provides

some empirical evidence that economies with high

levels of en-

try and international trade restrictions suffer severe growth slowdowns as they approach

the world technology frontier. Finally, Learner (1998), Robinson and Nugent (2001) and

Moav and VoUrath

Galor,

vestment in

may

initially

human

(2003) discuss the potential opposition of landowners to in-

capital.

For example, Galor

et al.

emphasize how land abundance

lead to greater income per capita, but later retard

human

and economic development. None of these papers contrasts the

lation

democracy and oligarchy or

The

rest of the

paper

is

identifies the

dynamic

organized as follows.

capital

accumu-

trade-offs

between

costs of oligarchy.

Section 2 describes the economic en-

vironment, and characterizes the equilibrium for a given sequence of policies.

Section

3 analyzes the pohtical equiMbrium in democracy and ohgarchy, and compares the out-

comes. Section 4 discusses a simple model of changes of regime between ohgarchy and

democracy. Section 5 concludes.

2

The Model

2.1

I

The Environment

consider a non-overlapping generations

There

is

a rmique

agent has a single

final

economy consisting of a continuum

good which can be used

off'spring,

and

is

for

consumption or

1 of dynasties.

for bequest.

Each

imperfectly altruistic with the utility function:

u^^{i-py^'-^^p-^{ciY-'{b^,,y-4,

(1)

where

the consumption of agent j at time

is

cj.

and

offspring,

zj is the

6^^j is

t,

the bequest he leaves to his

(non-pecuniary) cost of effort that the agent incurs

if

he becomes

an entreprenem:.

This utihty function

convenient since

is

impHes a constant savings rule

it

for

each

agent of the form:

^+i=W,

where W^

is

the total income of the agent at time

utility function of agent j at

turn the

I

sum

e

—

>

0.

e of

The reason

can otherwise

=

0,

specific

new

there

is

demand

also exist other equilibria,

to

.

income

is

in

death

is

and

economy with

to avoid the case where the

a range of wage rates, which

In other words, in the economy with

in this case, the limit e -^

picks a

set of equilibria.

economy

distinction in this

up a firm

= Wl — z\ Total

i.e., Wl = Wl + h{.

1/^

for labor for

arise in the oligarchic equilibrium.

and capitalists/entrepreneurs on the

or set

implies that the indirect

with a small probability e in every period,

for introducing the possibility of

one from the

The key

(dies)

W^,

It also

dynasties are born. I will consider the Umit of this

exactly equal to the

may

t.

simply given by

t is

of earned income, VF/, and bequests,

supply of labor

e

time

assume that each dynasty disappears

and a mass

(2)

is

other.

between production workers on the one hand

Each agent can

become an entreprenem:.^^ While

all

either

be employed as a worker

agents have the

same productivity

as workers, their productivity in entrepreneiu-ship differs. In particular, agent j at time

t

has entrepreneurial talent

an agent needs to

set

G {A^,A^] with A^ <

al

up a

firm, or alternatively,

up a new firm may be

father. Setting

A^

To become an entrepreneur,

.

he could inherit the firm from his

costly because of entry barriers created

by existing

entrepreneurs.

Each agent

talent a[

a firm.

therefore starts period

G {A^ A^], and

si

,

I will

also refer to

G

t

{0, 1}

with a

level of

bequest (income)

h{

society,

he

an agent with

may be

=

s^

1

as a

member

politically

more

influential

Within each period, each agent makes the following

denoted by

c^,

In addition

if z^

(effort),

a bequest decision denoted by

=

1, i.e., if

of the "elite", since he

6^_,.i,

barriers),

wiU

and

in

than non-ehte agents.

decisions: a

consumption decision

and an occupation choice

%{

G

{0, 1}.

the agent becomes an entrepreneur, he also makes investment

employment, and hiding decisions,

^^See, for example, Banerjee

entrepreneurial

which denotes whether the individual has inherited

have an advantage in becoming an entrepreneur (when there are entry

an oligarchic

,

and

Newman

el,

ll

and

hi,

where

hi denotes

whether he

(1993) for a model of occupational choice of this type.

incurs an investment and operation cost of el

will refer to

profits of

+

With some abuse

K'.

as the profit function. Given a tax rate Tj

tt

an entrepreneur with talent

(r„

TT

li, ei,

ai w,)

i.e.,

=

hi

1,

and a wage rate Wt

>

0,

I

the net

a^ are:

= i^(a^)-(e^y-(/^)- -

as long as the entrepreneur does not hide his output,

output,

of terminology,

=

hi

i.e.,

he avoids the tax, but loses a fraction 5

^ - kX,

-

w^lj

0.

<

1

If

(4)

he instead hides his

of his revenues, so his

profits are:

TT

{ruli,ei,ai,wt)

The comparison

= ^{ainei)'-^{lir - wtli 1 —

ei

a

of these two expressions immediately impUes that

-

if tj

kX.

>

6, all

entrepre-

neurs will hide their output, and there will be no tax revenue. Therefore, the relevant

range of taxes

will

be

0<Tt<5.

Since, in the presence of entry barriers, entrepreneurship

additional cost Kt for agents with

an agent of type

si

=

0,

il

=

an

1) entails

the net gain to becoming an entrepreneur for

a function of the pohcy vector

(5^,0^) as

(i.e.,

(kt, Tt),

and the wage

rate, Wt,

is:

U(kt,Tt,Wt

where the

last

I

sl,al) =meiX-K(Tt,ll,el,al,Wt)

term indicates that

if

-

(1

-

sl)ktX

(5)

the agent does not inherit the firm from his father,

he will have to pay the additional cost imposed by entry barriers. ^^ Notice also that

11

the net gain to becoming an entrepreneur, since the agent receives the wage rate Wt

is

irrespective (either working for another entrepreneur

—thus having to hire one

himself

imphes that an agent

will

less

—when he

worker

become an entrepreneur

become an entrepreneur only

if

Il(^kt,Tt,wt

^^Private sales of firms from agents with

when he

s^

=

sl,al)

\

1

>

a worker, or working

for

an entrepreneur). This feature

i£ Tl (^kt, Tt,

Wt

\

si

,

al)

>

(and can

0).

to those with

equivalently assumed to be subject to the entry cost Kt). This

we

is

is

is

Sj

=

are not allowed (or they are

without

loss of generality, since, as

where the equilibrium wage is

do not have the funds to finance the purchase of existing firms from the

will see below, entry barriers exist only in the oligarchic equilibrium,

zero and agents with

s^

=

incumbents.

Note that private sales of firms without any entry barrier-related costs would circumvent the inefficienfrom entry barriers. The absence of such sales, and consequently the existence of real effects of entry

barriers, seems plausible in practice (see, for example, Djankov et al., 2002, on the relationship between

entry barriers and various economic outcomes).

cies

10

Labor market clearing requires the

demand

total

Since entrepreneurs also work as workers, the supply

for labor not to

is

equal to

exceed the supply.

1, so:

lldj<l,

iilldj=

(6)

Jjeit

where

It is

the set of entrepreneurs at time

useful at this point to specify the law of

It is also

which determines the "type" of agent

by equation

(2).

a firm, then

liis

The

transition rule for si

is

Sq

=

that there

is

straightforward:

offspring inherits a firm at time

for all j,

and

also s^

=

if

motion of the vector (6j,Sf,aj)

As already noted, bequests are given

j at time t}^

^^+1

with

t.

=

i

+

1

,

agent j at time

if

t

sets

up

so

^l

(7)

dynasty j

is

born at time

Finally, I

t.

assume

imperfect correlation between the entreprenemrial talents of different agents

within a dynasty, and assimae the following Markov structure:

{A^

with probability

A^

G

cfl

Here

(0, 1).

with probability

with probabihty

an

in entrepreneiuship conditional

is

on

is

is

his father

i.e.,

an <

1,

is

,

.

^'

'

having high productivity, and gl

It is

natural to suppose that

more hkely to be highly productive

important for the results

dynasty,

1 - (7jy

I- a^

al

the probability that an agent has high productivity

probabihty when his father has low productivity.

so that an individual

if

with probability ai

A^

A^

where aH^

= A"

if a{ = A^

ii 4 = A"

if Gj = A^

gh

if

his parent is

is

the

uh > ct/,,

so. What

imperfect correlation of entrepreneurial talent within a

so that the identities of the entrepreneurs necessary to achieve

productive efficiency change over time.

It

can be

verified easily that

M = --f^G (0,1).

^^In fact,

what

is

important for the purposes here

is

the subvector

I

Sj

,

a^

I

.

Bequests are introduced to

and the incomes of current elites, which plays a role in Section 4. For

most of the paper, there is no need to keep track of the distribution of bequests. It is also worth noting

that the model could be set up with infinitely-lived agents, with little change in the results, though the

analysis becomes somewhat more complicated, because agents would have to take into account the future

implications of setting up a firm and becoming part of the elite. Since these issues are not central to the

create a link between past profits

focus here,

I

opted

for the

non-overlapping generations setup.

11

the fraction of agents with high productivity in the stationary distribution

is

(1

— M) ai)-

Since there

a large number of agents,

is

I

(i.e.,

is

to

is

1,

so that, without entry barriers, high-productivity entrepreneurs generate

demand

any point

assmne that

MX >

ficient

— an)

a continuum of

agents), wliich implies that the fraction of agents with high productivity at

I

(1

appeal informally to the weak law

of large nimibers (ignoring comphcations related to the fact that there

M. Throughout

M

employ the

as large; in particular,

I

entire labor supply. Moreover,

assume A >

I

more than

svif-

M as small and A

think of

which ensures that the workers are always in the

2,

majority and simpUfies the pohtical economy discussion below.

Finally, the timing of events within every period

1.

Entrepreneurial talents,

2.

The entry

3.

Agents make occupational choices,

4.

Entrepreneurs make investment and employment decisions,

5.

The labor market

6.

The tax

7.

Entrepreneurs make hiding decisions,

8.

Consmnption and bequest

Note that

I

barrier for

rate

[a^], are

new

clearing

and similarly

:

[0, 1]

—> {A^

,

reahzed.

entrepreneurs

wage

on entreprenetus,

used the notation

the mapping sn

J,

is:

[zj]

[e], /j]

rate, Wt, is determined.

rt.,

is set.

decisions,

[a^]

kt is set.

[/ijl

[cj, 6^^;^]

are made.

to describe the whole set [a^]

.^ ^,

,

or

more formally,

>1^}, which assigns a productivity level to each individual

for [zj], etc.

Entry barriers and taxes wiU be

set

by

different agents in different political regimes

as will be specified below. Notice that taxes are set after the investment decisions, which

can be motivated by potential commitment problems whereby entrepreneurs can be "held

up" after they make their investments decision.

employment decisions are made,

it is

Once these investments

in the interest of the workers to tax

are simk:

and

and redistribute

entrepreneurial income.-'^

^^This timing of events

is

adopted to simplify the analysis and the exposition. Because there are only

12

2.2

Analysis

I start

with the "economic equilibrium" which

the (subgame perfect) equilibrium of the

is

economy described above given a policy sequence

more

formally, let

ocj.

=

(il,elJl,hl,cl,

{kt, Tt}t=o

Definition (Economic Equilibrium) {[5^]}.

type

ket,

(bPf.,sl,al), xl

i.e.,

equation

I

now

(2), (7)

and

(8)

j, (1),

and wt

given

characterize this equiUbriiim. Recall that Sq

entry barrier would create waste, but not affect

all

fixed costs of operation

entrepreneurs will hire the

where, recall that,

maximum amount

=

4=

can be written as

Cj

=

Now using the

=

n

(kt,

,

Tt,

Wt

I

=

(1

— fi)^/"ajA

= -^-(1 1

—Q

=

0,

any positive

scale technology

Given

this,

E

imply that

It,

investments will be:

(10)

where

fj is the

tax rate expected

Tt).

(9)

and

(10), the net

gain to entrepreneur-

equiUbrium wages, the status

can be obtained

si, a{)

t.

Ttf/^aiX.

=

ko

(9)

-

ship, as a function of entry barriers, taxes,

talent,

for all j,

X,

equihbrium factor demands,

and entrepreneurial

and suppose

for all j,

of labor. Thus, for all j

(1

at the time of investment; in equilibriimi, ft

Sj^xi "^t+i))

enters entrepreneiorship)

the set of entreprenemrs at time

/j is

(Alternatively, (10)

who

(&^_|.i,

mar-

[x^].

and the constant returns to

II

{tWfjj^Q

clears the labor

in the next period,

so that in the initial period there are no entry barriers (since Sg

The

t.

given poUcies kt,Tt, the wage rate Wt and his

if,

Each agent's type

then follows from equations

at time

and a sequence of wage rates

gi

maximizes the utihty of agent

(6) holds.

define this equilibrium

be the vector of choices of agent j

6^_,_j)

constitute an economic equihbritun

To

•

i

si of

the agent

si)ktX.

(11)

as:

TtY^'^aiX

- WtX - kX -

{1

-

two types of entrepreneurs, it turns out that if workers choose the tax rate before investment decisions,

they will set r^ =

(see Appendix A). The timing of events here implies that they cannot commit to

this tax rate, and consequently ensures a positive level of redistribution. In Appendix A, I show that

the main results generalize to an environment where there are more than two levels of entrepreneurial

productivity and where voters set taxes Tj at the same time as kt, i.e., before investment decisions. In

this case, voters choose Tt > 0, trading off redistribution and the disincentive effects of taxation, as in,

among others, the models by Romer (1975), Roberts (1977), and Meltzer and Richard (1981).

13

^

Moreover, since

=

Xdj

J. J

=

/j

and the

1,

A for

all j,

the labor market clearing condition (6) implies that

mass of entrepreneurs

total

it= [

<

dj

any time

at

is:

1/A.

Jjeh

Tax revenues

at time

Tt

and the per capita lump-sum transfers are given

t

=

E W = Y3^^*(l - rO'^A J]a^

jeit

Who

will

shows that

any

for

Sj

and

dl,

Wt

and the

= A^

agents with al

=

si

\

and

5^

1,

= A^) > U

al

first

=

Sj

We

=

will

depend on

can then define two

economy? Inspection

in this

term

will

[kt, Tt,

Wt

|

s^, Qf)

>

11

of (11) immediately

(A;^,

Tj,

1^(15^

=

0, a{

always strictly greater than the third term. So

is

choose

=

Zj

0,

= A^

the occupational choice of agents with al

and

(12)

jeit

become an entrepreneur

11 {kt,Tt,

as:

becoming workers.

and

=

si

On

the other hand,

and of those with

1

al

= A^

kt.

different types of equilibria:

1.

Entry equilibrium where

2.

Sclerotic equilibrium

all

entrepreneurs have al

where agents with

=

si

= A^

become entrepreneurs

1

irrespective of

their productivity.

An

n

entry equihbrium requires that

[kt,Tt,Wt

I

si

=

1,

"

1

ai

— a (1

=

-

A^) <

0,

TtY^'^A''

IT

that

(^kt,

Tt,

Wt\

=

si

0, al

= A^^ >

and

is:

-K-kt>Wt> -^(1

—

a

1

Therefore, there wiU be an entry equihbrium only

- tO'/"A^ -

/c.

if

-^-{l-rtY/^{A''-A'^)>kt,

1 — a

(13)

'

i.e.,

is

only

if

the net marginal product of labor of a high-productivity non-elite entrepreneur

greater than that of a low-productivity

the other hand, only

if

the converse of (13)

Moreover, in an entry equilibrium,

i.e.,

elite.

is

A

sclerotic

equihbrium

emerge, on

the case.

when

(13) holds,

we have

{^(l-r,)V">l^-K-A:,;0|.

14

will

(14)

=

A^)

This follows because, in eqiiilibrium,

If it

were

11

(fcj,

r^, lut

si

\

strictly positive, or in other words, if the

=

0, al

= A^)

wage were

less

must be equal

than w^,

all

would be "excess demand"

for labor.

This argument also shows that

it

=

agents with

MX

high productivity would enter entrepreneurship, and since, by assumption,

>

this

economy. Labor supply

ing as a function of the wage rate. This

holds, so that there exists

demand

portion

i.e.,

MX

supply at the wage given in

>

1

1,

while labor

demand

is

demand

decreas-

drawn under the assumption that

figiu:e is

first

(13)

portion of the curve shows the

= A^ and sj — 1, and the second

those with aj = A^ and si = 0. These two

agents with aj

high-productivity non-ehtes,

groups together demand

constant at

an entry equilibrium. The

of high-productivity ehtes,

is for

is

there

1

1/A.

Figure 2 illustrates the entry equilibrium diagrammatically by plotting labor

and supply in

to zero.

i.e.,

workers, ensuring that labor

demand

intersects labor

(14).

LS

k

1-tJ«^^-k

1

1

!!;(>-',)"*'-'

LD

"

l-a

k-TJaA^-K-k^

'

"

—

xu

1

Figmre

2:

Labor supply and labor demand when

(13) holds

and there

an entry

exists

equiHbrium.

who

In a sclerotic equilibrium, on the other hand, low-productivity agents

si

=

,r^{l - Ttf'^A^ -

k\

firm from their parents will remain in entrepreneurship,

deaths so that e

Wt e [max

=

0,

we would have

{j^{l - Ttf/'^A" - k -

exactly equal labor supply

supply of

1.

if

=

1/A and

kt\Q]

for

i.e.,

Sj_;^.

If

inherited a

there were no

any

,

labor

demand would

— 1/A agents demanding exactly A workers each, and a

Hence, there would be multiple equiUbrium wages. In contrast, when e

the measure of entreprenetirs

who

could pay a wage of Yr^(l

15

~

Tt)^l°'A^

—

k

is

total

>

it

0,

=

(1

—

at

any wage above the lower support of the above range. This imphes that the equihbrium

<

e) it_i

1/A for

wage would be equal

is

>

all t

thus there would be excess supply of labor at this wage, or

0,

al

economy where e

—

>

0,

=

it

In the remainder,

1/A.

which picks

I

t^^I°-A^

= A^

between entrepreneurship and working, in equilibrium a

entrepreneurship, and

—

{jz^{l

wage agents with

Since at this

identical to (14).

max

to this lower support,

and

sufficient

si

~k—

=

kf,

O},

which

are indifferent

number

of

them

enter

focus on the Umiting case of this

max {y3^(1 — TtY^^A^ —

wage even when labor supply coincides with labor demand

k

for

—

kt;0] as the equilibriimi

a range of wages. ^*

LS

^

ik

^Jl-.J«.^-.

LD

1-E

Figure

3:

1

Labor supply and labor demand when

(13) does not hold

and there

exists a

sclerotic equihbrium.

Because (13) does not hold in this

Figure 3 Ulustrates this case diagrammaticaUy.

case, the second flat portion of the labor

agents with

aj.

= A^

and

Sj

=

1,

demand curve

is for

low-productivity ehtes,

i.e.,

who, given the entry barriers, have a higher marginal

product of labor than high-productivity non-ehtes.

Finally, since at time

i

Wo

^^In other words, the

=

we have

ko

=

0,

will also give

initial

period equilibrium will feature:

= max |-^(1 - ro)^/°A^ -

wage max-^ 13^(1 ~ TtY^^'A^ — k — kt;0>

equilibrium set where the equilibrium correspondence

I

the

is

o|

at e

.

=

is

the only point in the

(lower-hemi) continuous in

the relevant expressions for the case where e

16

k;

>

0.

e.

For completeness,

In the remainder of the paper,

I

assume

-^^{l-Sfl'^A" >K,

<

so that, for any tax t

and

5

In addition, note that at

ically,

A;

=

f

=

(15)

the equihbrium wage

0,

is

positive.

entrepreneurs have high productivity.

0, all

More

specif-

define

^i,

=

Pr

{al

= A"

as the fraction of entrepreneurs at time

the economy starts with

^*

_

~

ixq

=

1.

CTHl^t-i

J

=

1?,

who

t

The law

+

=

1)

I

=

(g^'

A""

\j

G h)

are high productivity. In the initial period,

of motion of

- /^i-i)

0-^(1

Pr

/i^ is

then given by:^^

(13) does not hold

if

.

\

This law of motion also imphes that

(13) holds

if

(13) never holds, lim4_^oo

if

fJ-t

=

.

^^^^

•

1

^<

^i i-^-,

the frac-

tion of high-productivity entreprenexirs limits to the average fraction of high-productivity

agents in the population.

The

following proposition summarizes the

main

results in this subsection (proof in the

text):

Proposition

Given a policy sequence

1

equihbrium, there are

=

it

{kt,Tt}f.^Q-y

,

an equihbrium always

exists.

In

1/A entrepreneurs and each entrepreneur hires A workers, and

undertakes the investment level given by (10), and the equihbrium wage

is

given by (14).

In addition:

• if (13)

holds at

tivity, i.e.,

is Ait

=

Zj

=

i,

an individual becomes an entrepreneur only

= A^

=> Qj

1

does not hold at

t,

productivity entrepreneurs

with

19

For e

>

he has high produc-

and the fraction of high-productivity entrepreneurs

1;

• if (13)

• if (13)

,

if

the equihbrium has

is /Xj

=

anl-i-t-i

=

0, this

1

,

and

satisfies limt ^oo

equation

£

^*

I

1

is

+

modified

(1

fit

=

=

+ cl(1 —

never holds, then the equilibrium has

yUg

i-j.

M<

/i^

=

s-j.,

and the

fraction of high-

A't-i);

anj-i't-i

+

"^/-(l

1.

to:

e) (cTH^t't-i

+

crz,(l

1

—

Mt-i))

if

(13) does not hold

if

17

(13) holds

~

/^i-i)

starting

Political Equilibrium

3

To obtain a full political equilibrium, we need to determine the policy sequence

I will

1.

{kt, rt}^^Q

^

consider two extreme cases:

Democracy: the poUcies

and

kt

r^ are

determined by majoritarian voting, with each

agent having one vote.

2.

Oligarchy

among

voting

the policies

(elite control):

the ehte at time

t.

I

and

kt

take the ehte to be those

firm from their parents, or in other words those with

In this section, oligarchy

is

determined by majoritarian

tj are

St

assumed to be "technological"

=

who have

inherited a

1.

in the sense that irrespective

of the exact pohtical institutions, those with control of the productive resources of the

society

and greater income have more say

pohcy choices

reflect their preferences.

whether the society

in pohtical decision-making,

In the next section,

democratic or oligarchic

is

is

and consequently,

analyze a model where

I

determined in equiUbrium.

Democracy

3.1

The timing

of events imphes that the tax rate at time

decisions at time

decisions are

t,

t,

Tt, is

decided after investment

whereas the entry barriers are decided before. Both of these pohcy

made by

majoritarian voting.^° Recall also that the assumption A

>

2

above

ensures that non-elite agents are always in the majority.

At the time taxes are

set,

investments are sunk, agents have aheady

cupation choices, and workers are in the majority.

maximize per capita

transfers.

We

fj is the

voters.

tax rate expected by entrepreneurs and

output, and tax revenue wiU be

affect

n

U

This expression takes into account that

0.

Tt

is

if tj

their oc-

Therefore, taxes wiU be chosen to

can use equation (12) to write tax revenues

I

where

made

>

Tj is

5,

Tt

as:

>

the actual tax rate set by

entrepreneurs will hide their

a fxmction of the entry barrier,

kt,

since this can

the selection of entrepreneurs, and thus the X^,g/, al term.

At the time the entry

barrier, kt, is set, agents

choices. Low-productivity non-ehte agents,

^"Appendix

A

presents a

more general version

i.e.,

have not made their occupational

those with

s^

=

and

a^

=

A^, know that

of the model, which has both policy choices

simultaneously, and yields identical results to those in the text.

18

made

they will always be workers, and thus simply receive the equilibrium wage and transfers.

Therefore, the utihty of agent j with

t//

where

fej

is

=

Sj

= 6^+ <

al

= A^

+ Tt

[kt, Tt

and

ft)

{kt

I

the bequests he has inherited, and wl[kt

equation (14), but with the anticipated tax rate

is

f,)

\

equilibrium, naturally, Tt

wt

{kt\ ft)

=

ft)-

ft replacing

i.e.,

to

maximize

tUj {kt

same and they

the

also given

is

+

ft)

\

by

those with

Consequently,

(18).

Tt {kt,Tt

|

Sj

=

A

\

I

\

ft)

+

is

Tt {kt, Tt

\

Because taxes are set after investment decisions, workers prefer

redistribution of income

^^The

S

and w^

{kt

|

results are identical

does not depend on

when

^^

^^

such that:

ft)

-

=

Tt

T {kt, Tt

from the entrepreneurs to themselves

ft)

a pohcy sequence

is

Jt=o,i,...

L

{kt

as:

^^^^ ^^^^ {[^]}t=oi

and \kt,ft>

) t=o,i,...

(4, ftj e argmaxiWi

h,Tt

=

non-ehte agents are

all

democratic equihbrium

economic equilibrium given \kt,ftr

at Tt

,

non-elite agents will choose kt

and economic decisions {[^]}j^oi

'?'*(•

(fct,

al

shows that a democratic equilibrium can be defined

Definition (Democratic Equilibrium)

4,

all

= A^ may become

Tt, wt

sf = 0, al = A^)

and

11

(19)

are in the majority, the democratic equihbrium will maximize these

preferences. This analysis

I

conditioned on the expected

Since the preferences of

ft)-

is

Thus:

entrepreneurs, but as the above analysis shows, in this case,

so their utihty

is

the actual tax rate (this

= max S^^^il- ft)'/'' A''-i^-kt;o\.

High-productivity non-ehte agents,

0,

the equiUbrium wage given by

ft) is

because the labor market clears before tax decisions, so wl

tax; rate, fj; in

(18)

I

6 to

\

maximize the

ft) is

maximized

r^.^^

taxes are on income rather than output. In this case, the objective

[1 — Tt)wf{kt

ft)+Tt {kt,Tt fj), with Tj (A;t,Tt fj) unchanged

because tax revenues now include taxes from wage income, but this is offset by the lower tax

revenue from entrepreneurs, who are now paying taxes only on their net income, i.e., output minus wage

function of the median voter would be:

|

\

|

(this is

bill).

It

can be verified that this expression

derivative of this expression with respect to Tt

—

which

Y3^(l

is

maximized at

tj

=

S.

To

see this note that the

is

^

rv

always positive since, by definition, for

— Tt)~^ Xal >

is still

all

j

—

G

It,

we have t^(1 — 7"t)

°

Aa^

—wf >

wl, implying that voters would like as high a tax rate as possible,

19

0.

i.e.,

Therefore,

Tt

=

5.

-

Inspection of (17) and (19) shows that wages and tax revenue are both maximized

when

=

kt

so the democratic equihbrium will not impose any entry barriers.

0,

by protecting incimabents, and a

intmtive: workers have nothing to gain

is

since such protection reduces labor

demand and

= A^ The

and only

if

il

=

I

only

if

following proposition therefore follows immediately (proof in the text):

.

Proposition 2

if

lot to lose,

wages. Since there are no entry barriers,

only high-productivity agents will become entrepreneurs, or in other words

Qj

This

al

A democratic equilibrium always features Tt = 6 and kt =

= A^, and = 1. The equihbrium wage rate is given by

0,

and

il

=

1

/ij

a

-f = 1-Q (1 and the aggregate output

Y,^

-

sy/'^A"

K,

is

= Y^ = ^(l-J)V-A^ + 5iLJ)

1- a

1 - a

"

^^,

(20)

^

^

1-tt

Notice that in the

and the second term

equilibrium

is

first line

is

of (20), the

tax revenue at the rate

that aggregate output

is

term

first

Tt

=

is

total production net of taxes,

5^'^

An

important feature of this

constant over time, which wiU contrast with the

ohgarchic equilibrium.

Finally, note that since

n

{kt

=

0,Tt,wt

si

1

=

0,ai

= A")=U

{kt

=

0,rt,wt

\

= 1,4 = A^) =

sj

0,

high-productivity agents are indifferent between entrepreneurship and production work.

Nevertheless, entrepreneiirs earn greater incomes to compensate

costs of entrepreneurship. In fact, in

come

(net of bequests)

I

^^The expression above

have been subtracted.

^^To obtain

T

=

5.

periods, production workers have a post-tax in-

:^'^

W- = -^-(1

—

K,

all

them for the non-pecuniary

a

- 5Y^^A"

1

refers to total output,

Output net of these

-K + 5^^—^

—

"

A"",

before the costs of investment,

costs

is

(21)

a

given by q(1

—

e,

<5)-'/°j4^/ (1

and operation,

—

a)

+

aS{l

—

wage, (19) and tax revenues, (17), with r =

with equilibrium factor demands (9) and (10),

(21), use the expression for the equilibrium

To obtain

(22), use

the production function

(3)

and the fact that output is taxed at the rate t = f = 5, then subtract the

add W^ which is what the entrepreneur receives as a worker himself.

,

20

total

wage

bill

using (19), and

while each entrepreneur receives:

W^ = {1-

+ kX + W^ >

Sy/^'A^X

W"".

(22)

Oligarchy

3.2

In ohgarchy, only existing entrepreneurs (agents with

and

process,

elite is

=

1)

participate in the pohtical

determined by majoritarian voting among this

policies are

nature of the ohgarchic equilibrium

within the

si

is

set of agents.

The

simpUfied by the fact that the only heterogeneity

between high-productivity and low-productivity agents. This implies

that majoritarian voting wiU lead to the policies most preferred by whichever group

in

is

the majority within the ehte.

To

with

it

=

state this formally, let

=

St

This

1.

whereas

1,

an agent

at time

St

t,

=

1

j2t

fi^

from

is different

^j,

which

refers to the entreprenerus,

refers to the agents in the elite,

chooses

it

=

those with

i.e.,

St

=

and does not become an entrepreneiu, he

and thus takes part

wiU not be

be the fraction of high-productivity agents among those

in the determination of the tax rate,

i.e.,

1.

those with

Notice that

is still

though

if

in the elite

his offspring

in the ehte.^"*

In addition, note that the most preferred policies of an ehte agent with productivity

al are given

U^

where

=

6^ is

by

bi

kt

and

tj that

+ max {n

{kt,

maximize:

Tt,wt

the bequest the agent

I

=

l,a{)

;

hcis inherited,

the net return to entrepreneur ship,

Tt,

si

lUt,

O}

the

+ w\ (h

\

ft)

11 fiuiction,

given by (19),

is

+ Tt

{kt,Tt

from

(5)

\

ft)

above, denotes

the equilibrium wage rate and

given by (17), denotes transfers. This expression incorporates the fact that the agent

will

become an

Then

let

entrepreneiu- ordy

if

the net return to entrepreneurship

An

and economic decisions

<A;t,ft>

L

it

alternative modeling assumption

=

1. It

can be

characterized here

eqiuUbrimn

oligarchic

{ [2^] },^n

i

J t=o,i,...

would be to

I

a poUcy sequence

is

such that {[^]}j^oi

and \kt,ft\

economic equilibriiun given \kt,ft\

^*An

non-negative.

us define:

Definition (Oligarchic Equilibrium)

with

is

is

^^

^^

such that:

J t=o,i,...

limit the decision

on the tax rate only to agents

verified that the equilibrium in this case is identical to the non-cycling equilibrium

(i.e., it

does not contain cycles even

21

when

condition (24) holds).

*

>

if Jit

1/2, then

argmax {max (ll

[kt,ftj e

Wt\

{kt, Tt,

si

=

1,

si

=

l,a^

= A")

al

;

+

O)

Wt {k

\

ft)

+ Tt

ft)

+ Tt{kt,Tt

{kt, Tt

\

ft)]

kt,Tt

*

<

if /it

1/2, then

€ argmax {max

(kt.ft)

where

To

Tt {kt, Tt

\

ft) is

(n(fci,rt,ii;t

|

given by (17) and wf

{kt

characterize the oligarchic equihbrium, let us

productivity ehtes

(i.e.,

those with

=

si

and

1

al

=

\

=

A^) O)

;

ft) is

first

=

kt

G [ir^(l ~

0.

Equihbrium wage, given

ft)^^°'A^

—

in (19), will

Without

K, oo).

|

given by (19).

A^). Since these agents wiU remain as

to be as low as possible,

=

be minimized at wf

any generahty,

loss of

(/cj

consider the preferences of high-

an entrepreneur, they would always hke the wage and taxes

ft

+ iw"

0,

i.e.,

by choosing any

focus on a particular

I

point in this set,

kt

=

= -^{l-5)'/''A"-K.

—

k^

Next consider the pohcy preference

si

=

1

and

al

=

A^).

His payoff

is

he remains an entrepreneur, making

redistribution).

Or

it is

worker receiving income jz^{l

^

-

of a low-productivity ehte

maximized

=

kt

-

5)1/"

and

- k+

5)^^°'A^

[a{l

either

profits equal to

maximized by

(23)

a

1

Tt

yz^(1

by

kt

=

{jz^A^ —

=

-

S,

(i.e.,

k^ and

an agent with

X (plus

k)

when he chooses

6)'^^~°'^/"A^.

=

Tt

0,

when

wage and

become a

to

As long

as

+ 5{1 - (5)(i-°)/°] A" -K

1—

profits

tion.^^

from entrepreneurship are greater, and low-productivity ehtes prefer the

Therefore,

when

(24) holds,

both low-productivity and high-productivity

have the same preferences over pohcies, and vote

tion

is

for kt

=

k^ and

the ohgarchic equihbrium, and results in equihbrirun wages

In this equihbrium, aggregate output

Yt^

^^Note that

if

the pohcy of kt

= k^

and

Tj

=

when

= 0. This

wf = 0.^*^

tj

op-

elites

combina-

is:

= f^tj^A" +

1 — a

to remain in entrepreneurship. However,

first

is

(I

- pit)Y^A^

1 — a

(25)

elite would always prefer

between entrepreneurship

imposed, the low-productivity

deciding policies, the choice

is

with kt = k^ and Tt = 0, and production work with kt =Q and Tt = 5.

^^

This result also shows that even if taxes that only apply to labor income and transfers directed only

to the elite were allowed, there would be no need for the elite to use them, since wages are already at

their

minimum

value.

22

\

ft)}

;

where

^ij

=

an/J^t-i

M,

sequence converging to

aggregate output

Urn Yt^

The reason

^ given by (16), with

+ <^l{^ ~ A^t-i)

y^-^ is

/ig

=

Since

1.

/Xj

is

a decreasing

also decreasing over time with:^^

—^ (A^ + M{A" - A^))

= Y^ =

(26)

time goes by, the comparative advantage of the members

for this is that as

of the eUte in entrepreneiirship gradually disappears because of the imperfect correlation

between parents' and children's

talents.

Another important feature of

ings) inequahty.

Wages

this

are equal to

each entrepreneur earns

and

XYf.^,

equiUbrium

0,

is

that there

is

a high degree of (earn-

while entrepreneiKS earn positive profits

—

in fact,

their total earnings equal aggregate output.

This

contrasts with relative equahty in democracy.

when

Alternately,

preferences from high-productivity ehtes.

Therefore, the equilibrium depends on the

ratio of high-productivity vs. low-productivity ehtes,

i.e.,

on

When

/ij.

—

productivity ehtes are pivotal and the above characterization applies

=

ft

0.

poUcy

(24) does not hold, low-productivity elites have different

when

In contrast,

equihbriimi pohcies are

<

Jl^

—

kt

p.^.

i.e.,

>

1/2, high-

kt

=

k^ and

and

1/2, low-productivity elites are in the majority

and

=

fj

Therefore, at date

5.

the equilibrium will

t,

be identical to the democratic equihbrium. However, entry of high-productivity agents

when

into entrepreneurship

will

/ij_,_i

time

+

t

and the eqmlibrium

1,

alH <

and

t

satisfying

t

=

will revert

when

taxes. Therefore,

periodicity

gh <

implies that

/jj

be greater than 1/2 and high-productivity

k^ and

for

=

kt

1/2, then even at

will prefer

A;^

=

t-|- 1

and

Then provided

1.

elites will

:

<

^^

= mint

f

be

that

an >

1/2,

in the majority again at

back to the sclerotic one with entry barriers

(24) does not hold, the

mint E N

can be defined as

f, t

=

equihbrium wiU be cyclic with

1/2. Alternatively, using the fact that

N

e

:

u,

i

<

i/-=^.28

if

Jl^

=

/i^

on the other hand,

low-productivity agents will be the majority within the ehte,

r^

=

5,

so the ohgarchic equilibrium will be identical to the

democratic one.

Therefore,

we have the foUowing proposition (proof

Proposition 3

as given

by

E

(24) holds, then the oligarchic equilibrium has rj

and the equilibrium

(23),

^^For the case where e

-

(1

mJt^A^

and

be

less

than 1/2

/U£

=

1

>

r^ =

^*In other words, this

we have

is

0,

Jlf

<

we have

^

^^

is

=e+

=

and

always sclerotic and features wl

=

+ '^lO- ~

=

[\

—

e) [aiilJ-t-i

Mt-i)) ^"^

"^t^

0.

=

kt

k^

Aggre-

l^tT^-^^

"'"

(a^ + ,_,\%:l^^^J A" - A^)).

the level of

for the first

while

in the text):

time at

t

fJ-t-i

=

i.

such that were the equilibrium to remain

But because the equilibrium switches

1/2.

23

sclerotic,

/ij

would

to the entry equilibrium,

gate output

If (24)

economy

and

an >

does not hold and

starts with

=

/Xq

and

1,

satisfies

the law of motion

= i where i is defined as t = min i G N

kt = k^ as given by (23) lit ^ ni for any

:

=

/if

and jumps up

ni,

t 7^

/.ij

1/2, then the ohgarchic equilibrium

t

any n G N, and

If (24)

1 ii t

to

is

=

an <

t

The

=

ni

~J'^

n G N, and

nt for some n G N, so

iZ^A^ when

does not hold and

< ^

|l^_l

=

given by (25) with ^j

for

it

.

Tt

The

= anfJ-t-i + cl(1 — A^t-i)

The equilibrium has r^ =

= 5 and kt = if t = ni for

anlJ^t-i

+ "^/-(l ~ A^t-i)

declines during

all

if ^ 7^

ni

periods where

some n G N.

is

identical to the

2.

Comparison Between Democracy and Oligarchy

last

two subsections highlighted a number of

oligarchic equihbria. This subsection

differences

between democratic and

compares aggregate output and

democratic and ohgarchic equihbria.^^

To

simplify the discussion,

where (24) holds, so that the oligarchic equihbrium does not have

The first important

equihbritmi,

i.e.,

Y(f,

result

is

y^ =

>

Therefore, for aU 5

because

it is

is

its

I

dynamics in the

focus on the case

cycles.

that aggregate output in the initial period of the oligarchic

greater than the constant level of output in the democratic equi-

hbrium, Y^. In other words,

0,

5

>

—

if

0,

then

—

- sV-^A"" < Y.^ = -^A"".

-^(1

(i-*)-A"<n'

a

oligarchy initially generates greater output than democracy,

protecting the property rights of entrepreneurs.^*^ However, the analysis also

shows that Y^^ dechnes over time, while

economy may subsequently

depends on whether

(1

is cyclic.

jj.^.

1/2, then the ohgarchic equilibrixmi

democratic equihbrium in Proposition

3.3

with

given by (26).

some n G N. Aggregate output

for

= j^A^

given by (25) and decreases over time starting at Yff

Yf = Y^as

limt^oo

until

is

- 5)^ A"/

(1

-

Y^

q)

is

fall

Y^

is

behind the democratic

greater than

> {A^ + M[A" -

Y^

as given

A^)) /

Consequently, the ohgarchic

constant.

(1

-

society.

by

(26).

q), or

Whether

it

does so or not

This wiU be the case

if

if

l-c

(1-5)^>^ + m(i-^).

(27)

can be verified that all the results here also hold for the comparison of net output levels.