Document 11163006

advertisement

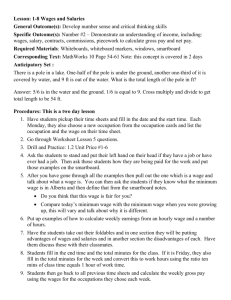

^^^«%. ^' Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Boston Library Consortium IVIember Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/observationsconjOOkrue ',tm&J working paper department of economics OBSERVATIONS AND CONJECTURES ON THE U.S. EMPLOYMENT MIRACLE Alan Krueger Jorn-Steffen Pischke No. 97-16 August 1997 , massachusetts institute of technology 50 memorial drive Cambridge, mass. 02139 WORKING PAPER DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS OBSERVATIONS AND CONJECTURES ON THE U.S. EMPLOYMENT MIRACLE Alan Knieger Jorn-Steffen Pischke No. 97-16 August, 1997 MASSACHUSEHS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY 50 MEMORIAL DRIVE CAMBRIDGE, MASS. 021329 MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE "'OGY 4]) LlBMMMItS JAN 19 1998 — Observations and Conjectures on the U.S. Employment Miracle Alan B. Krueger Jorn-Steffen Pischke Abstract This paper has three goals; first place U.S. job growth to perspective by exploring cross-country differences growth. This section finds that the U.S. has especially female workers countries. The market has markets are rigidities into employment flexible rigid. wages and employment The second goal of the hypothesis. Although greater employment in in many European from relative wage at wage to absorb added worl<ers a greater rate than most phenomenon practices, paper is its is whereas European labor inflexibility population, the slow growth absorb so skill in groups alone. Furthermore, a great deal of labor at a constant real wage leads to the third goal: to speculate on other explanations to successfully markets probably contributes to the countries appears too uniform across market adjustment seems to take place managed that the U.S. labor to evaluate the labor flexibility creating jobs for international employment and population in managed leading explanation for this U.S.'s comparative success to result — in many new in the U.S. This why the U.S. has entrants to the labor market. We conjecture that product market constraints contribute to the slow growth of employment in many countries. Observations and Conjectures on the U.S. Employment Miracle Alan B. Krueger Princeton University and NBER and Jorn-Steffen Pischke Massachusetts Institute of Technology and NBER June 4, 1997 August 14, 1997 First Draft: This Draft: *We thank Roope Uusitalo for excellent research assistance, and Lars Calmfors, David Card, John Dunlop, Jim Heckman, Bertil Holmlund, Joachim Moller, Sherwin Rosen, and Cecilia Rouse for helpful comments. Naturally, the authors are responsible for all views expressed. This paper expands the analysis in an earlier paper by Alan Krueger entitled "The U.S. Employment Miracle in Perspective." The data from the "Qualifications and Careers" survey was obtained from the German Zentralarchiv fur Empirische Sozialforschung at the University of Koln (ZA). The data were collected by the Bundesinstitut fur Berufsbildung and the Institut fur Arbeitsmarkt und Berufsforschung. Neither the producers of the data nor the ZA bear any responsibility for the analysis or Interpretation of the data in this paper. Compared to most of Westem Between 1985 and 1995, impressive. U.S. and by an average of just growth Europe, employment growth 5.7% for in Germany, France and the employment growth has caused the unemployment April in it 1997 much is of for the first time since 1973. employment A why the Strong U.S. fall Australia. With these statistics the recent U.S. experience below 5% in 8% as background, frequently characterized as an is miracle. employment growth has been remarkably steady since the Great Depression, growing by intervals since 1940, and by more than 15% at least in all 10% in each of the but five of these intervals. U.S. employment growth has been aided by comparatively fast population growth. example, between 1985 and 1995 the working-age population 11.4%, while the Employment U.K.'' rate in the U.S. to longer term perspective reveals that U.S. 58 ten-year in in Meanwhile, the unemployment rate exceeds Western Europe, Canada and not hard to see the U.S. has been example, employment grew by 16.6% the private sector has been especially impressive in in it increased by an average of 6.8% in in For the U.S. increased by Germany, France and the U.K. combined. This paper has three goals. international perspective. is A First, to put the Nonetheless, the U.S. has managed to employment growth in employment growth in the U.S. working-age population in the U.S. large share of the stronger attributable to comparatively faster growth of the U.S. absorb added workers ~ especially female ^These figures, and subsequent employment figures in the paper, are based on BLS data which put foreign countries on a similar basis as the U.S. OECD employment figures are generally similar. One major difference, however, is that the BLS data pertain to West Germany after unification. 3 workers -- into employment economy created so many that the U.S. labor market is flexibility jobs for our growing population? market probably contributes to the U.S.'s comparative success of the labor market. some facts that challenge the skill groups to result wage in explanations the U.S. why from relative seems Furthermore, a great deal of labor market adjustment managed to successfully of the wage its of this feature many European wage inflexibility. to take place at This leads to the third goal of the paper: the U.S. has in is flexibility creating jobs for in employment in The greater paramount importance Most importantly, the slow growth countries appears too uniform across real Although hypothesis. rigidities rigid. The second goal wages. well as relative has the U.S. The leading explanation and European labor markets are wages as to evaluate the labor population, there are How a greater rate than most countries. is flexible, applies to the level of real paper at a constant To speculate on other absorb so many new entrants to the labor market. 1. An Analysis The of Employment Growth analysis makes use in of the 10 Countries Bureau of Labor (BLS) international Statistics's estimates of employment and population. These data use U.S. concepts of employment and working-age population for country estimates reported to the employment concepts. schooling age age limit, in 10 major countries. OECD for breaks in The minimum working age the country (14-16). so adjustments were made The U.S. Briefly, series is the and BLS for adjusts official major deviations typically set at the in compulsory employment data do not have an upper to the data for countries which limited employment 4 to workers below a certain age. Population pertains than the minimum working age. Table 1 long-term trends for more presents regression estimates of the log of Over term and individual country dummies. exceeded the Germany's log of the rest of the working-age population model the U.S. trend term total 1 the falls to added first Germany accounts The models same in all to the regression .40 percentage points country in much, but not column at different rates. employment. variables, 1 all, of its In column model. Interestingly, above the world (2), not be the case. column to (3), 2, the in this trend; thus, for by faster slower population growth effect of population in growth to be the For example, various economic and different countries to translate population In year lower trend-growth of employment. and 2 constrain the may This may cause dummy According to column the U.S.^ for countries. social rigidities growth in linear of percentage point per year, while about 60 percent of the faster U.S. employment growth can be accounted population growth column U.S. employment growth sample by about 0.7 points per year. is 10 for international data.) employment on a this long period, sample by approximately trailed the rest of the BLS German employment, U.S. and in details of the older is The data are annual, from 1959 through 1995 major countries.^ (See Godbout, 1993 To estimate to the civilian population that the population variable is growth into job interacted with 10 allow for differential effects of population growth on The countries can be grouped into three groups: countries where a ^For Australia, comparable employment data are only available for 1964-95, and for the Netherlands they are only available for 1973-95. ^Godbout (1993) also finds that faster population growth stronger employment growth in the U.S. is a major reason for the 5 proportionate increase in employment (U.S., in population is associated with more tinan a proportionate increase Canada, the Netherlands); countries where employment growth is proportionate to population growth (Australia, Japan, and Sweden); and countries where employment growth Italy and the Figure is less than proportionate with population growth (France, U.K.). 1 graphically illustrates the relationship population growth, over five-year intervals. that population growth accounts for rises A somewhat more than is between employment growth and regression through these points indicates 56 percent Moreover, the slope of the relationship employment of the variability in Thus, 1.27. same The men and women set of regression models across countries. for U.S. superior trend growth employment growth. over five-year intervals, proportionately with population growth. The aggregate employment data mask important treatment of Germany, differences Columns 4-6 of in the labor market Table 1 men, and columns 7-9 present estimates in employment is women greater for present the for women.'' than for men. Moreover, columns 6 and 9 indicate that the relationship between population growth and employment growth growth in varies by gender within several countries. female population hardly translates the coefficient on population International differences in is into greater In Japan and Germany, employment. over three times as great for In the Netherlands, women as for men.^ the relationship between population growth and employment "These regressions are based on unpublished data provided by the BLS. Connie Sorrentino for providing these data. We thank ^The Netherlands has an extremely high rate of part-time employment among women, which may explain the high coefficient for women (see Godbout, 1993). 6 growth are much greater We for women OECD have also used estimate the aggregate models estimate of the model coefficient on in employment data Table in column log population that restricted to the 10 countries used than they are for men. a is in Interestingly, the 1. OECD with (2) little Table less than 1, a wider set of countries to for data for employment even if rate. This employment is rises at the growth roughly supply of workers creates The the a country to the estimates in to work. Because the working is (slightly) -- in of of Table of first order approximation, proportion to the workers' -- but it does suggest in above the expect 1 of include would be working, but well within a standard OECD ^We are grateful to Sherwin to test According former East Germans German Socioeconomic Panel (GSOEP), we Germans worked Table 47% full full-time and 6.3% worked and part-time workers, the fraction of the marginal population that the ^The that the those workers. we would 1, of the former East figures data are because there may be unemployment as population many for OECD to provide jobs for a marginal population increment.^ column 3 45.2% rate the and West Germany provides a unique opportunity Using the 1995 wave calculate that time.° demand re-unification of East ability of same if the coefficient rises to 1.16 with a standard Says Law not quite 24 countries produce a However, 1. error of .04.^ Thus, for the industrialized world as a whole, to a countries tend to absorb population unweighted regression part- fraction model predicts error of the point estimate. For men the data are for 1963-94. Rosen for suggesting this test to us. ®ln calculating these figures, we try to implement the concepts that are used in the BLS international data. same sample restrictions and 7 model predicts it predicts that 73% 23%. The 46.1%, respectively women, II. actual -- but roughly of the marginal population employment slightly would be employed, and rates for former East lower than predicted for for women Germans were 65.6% and men and higher than predicted for the right ballpark. in Evaluation of Labor Market Riqidities: Employment and Population Growth by Skill Level The most common explanation its growing population countries. To some, is this for the U.S.'s that the U.S. explanation is has a more tautological. there would be no involuntary unemployment. account is for involuntary not the source of manifests to itself in greater success unemployment. An If flexible labor wages are is providing jobs for market than other perfectly flexible, then Thus, downwardly alternative view employment problems, in that labor rigid wages must market but inflexibility elsewhere in slower job growth. For example, restrictions on bringing inflexibility the economy new products market or on starting new enterprises could reduce job growth. Another potential form system. A number of Unemployment Insurance benefit availability -- of labor market "rigidity" involves the social insurance microeconometric studies have found that more generous (Ul) benefits -- in terms of both benefit levels and duration of are associated with longer durations of unemployment spells (see Solon, 1985; Katz and Meyer, 1989; Meyer, 1990; Meyer, 1995; and Hunt, 1995).^ ^Of course, this distortionary effect of Ul and other social insurance programs must be weighed against their desirable features, such as consumption smoothing during times of economic hardship. 8 These studies do unemployment not prove that generous however, because non-UI recipients new (e.g., of the more robust findings in Forslund and Krueger, 1996). More (e.g., see Layard, jobs fill connection in this cross-country studies associated with higher unemployment may entrants) those on the Ul program (see Levine, 1993). But one benefits reduce employment, is it is left noteworthy that that UI benefit generosity is and Jackman, 1991 and Nickell generally, social welfare benefits workers' reservation wages, rendering a floor on market available by wages similar may increase effect to in a minimum wage.^° In general, however, main source we find that the Europe and Canada's employment problems of conveyed by the widespread consensus which some people argue job growth. But just evidence that labor market it. This is in not to support of deny that by reforming its labor market will are the not as strong as is and the stridency with this view, some we suspect that any country that seeks is rigidities labor market rigidities restrict to solve its employment problems be disappointed, because more seems to be at work. In its downwardly simplest form, the labor market inflexible in Europe because of rigidities wage wages, unions, insiders or welfare programs. view floors, Wage is as follows: Wages established by legal are minimum floors are less of a constraint in the U.S. because unions represent only one-tenth of private sector workers, the real value of the minimum wage is quite low ($4.75 per hour in 1997), and the safety net is weaker. ^°See Calmfors and Forslund (1991) for a theoretical model of how social welfare programs can affect union wage setting, and related empirical evidence for Sweden. 9 The next link quite plausibly -- experienced a decline demand in demand shock has manifested and lower employment concluded "that in enough -- is to for less skilled itself in lower assume workers wages in industrialized countries the 1980s and 1990s. This for less skilled As Krugman (1994) Europe. all workers many notes, the U.S. in observers have growing U.S. inequality and growing European unemployment are different sides of the Beyond the same coin." This is a simple and appealing hypothesis. unemployment prediction of rising in Europe and growing inequality in the U.S., however, this explanation predicts that the decline in employment would be disproportionately concentrated among the groups of workers whose wages have fallen most evidence on in the U.S.; that this prediction is, among in an rise in unemployment highly educated workers rise unemployment. was substantial, Furthermore, countries. As evidence, between 1971-82 and 1983-90 the workers to that rates the for high Nickell ratio of in (or rise in in far, the a number of studies unemployment) countries with weak is overall employment growth. the EC Europe (with the exception of and roughly proportional U.S. rate of unskilled relative to skilled many European of Europe papers, Nickell and Bell (1995, 1996) find that between the Italy) for unemployment employment countries with strong overall in influential set of 1970s and 1980s, the in in the low-wage end of the labor market employment growth than In and young workers. So has been quite mixed. The findings challenge the hypothesis that the decline more concentrated less-skilled in an experienced workers that was and Bell cite educated workers rose from 3.8 to 4.2 in increase in the fairly similar to that of OECD unemployment to the overall data showing that rate for low educated Germany, from 1.7 to 10 2.0 in facts, Spain, and from 3.9 to 4.7 however, is that the overall ratio of the unemployment increase the in number a greater overall rise unemployment in the p. 307) conclude: in unemployment rate rose less in the U.S., unemployed than unemployment. rate difficulty in interpreting tliese would rates of unskilled to skilled workers of unskilled in One the United States. in In skilled still unemployed other words, whether so a constant imply a greater in countries with we measure changes Nonetheless, Nickell and Bell (1996, levels or logs matters. We have analyzed the broad-brush hypothesis that European unemployment has risen dramatically relative to that in the United States because there has been a substantial shift in demand against the unskilled in both places but relative wages are rigid in Europe and flexible in the United States. OECD The unemployment workers in We conclude that sought to find a this hypothesis relationship work as work is follows: "there less prevalent is little solid have achieved among youth and low-educated Their results indicated statistically insignificant and often wrong-signed correlations (see OECD, 1996; this inadequate. between wage compression and rates or employment-population rates a cross-section of countries. is evidence to p. 75). The OECD summarizes suggest that countries where low-paid this at the cost of higher unemployment rates and lower employment rates for the more vulnerable groups in the labour market, such as youth and women." Card, Kramarz and Lemieux (1996) examine trends in employment-to-population 11 rates in Canada and France, the U.S., the population find that each country in low-wage groups in into and the rate education-by-age Between 1979 and 1989 they cells. the U.S. suffered large real earnings declines, as to be expected. Additionally, they find a employment They group using comparable micro data sets." initial weak positive relationship The level of earnings. between the change decline in employment in the rates for lower-paid groups of American workers has been widely interpreted as a labor supply response, but we note it possible that despite their steep decline is above the full-employment equilibrium been a constraint as while the results for well. level for these workers so For France, the results employment are growth across age-education cells in for France is demand might have wage growth surprisingly similar. In unrelated to wages remained are quite different, contrast to the U.S., initial wage levels, a result of a labor market institutions that prevent wage adjustments. This But changes the initial in the employment-to-population rate wage level - employment wage rates in is wage probably as expected. France are only weakly related to have declined by about the same amount regardless of the initial that rigid relative wages have reduced employment level of the cell. This pattern is inconsistent with the view among especially the low-skilled in France. We trends by 1 979 and extend Card, Kramarz and Lemieux by comparing skill 1 groups in Germany and 991 outgoing rotation group the U.S. files of the For the U.S. wage and employment we pooled CPS. For each period, data from the we constructed "See Edin, Harkman and Holmlund (1996) for related evidence for Sweden. Especially for adults, their results are similar to Card, Kramarz and Lemieux's findings for France. 12 age-by-education groups using three education levels (high school or less, college or more) 60). college, and seven age groups (25-29, 30-34, 35-39, 40-44, 45-49, 50-54, 55- For each group, population rate (using we calculate the CPS mean log hourly wage and the employment-to- weights). Unfortunately, no large data set similar to the Germany. some CPS is We therefore constructed employment-to-population "Mikrozensus" published annually by the Statistical Office.''^ publicly available for rates using data from the This forces us to use the three education groups available there, which correspond to the school-leaving degrees of the various tracks of secondary school. Classifications by post-secondary education are also available, but the categories other than completed apprenticeship and university degree are so small as to render them useless for our purposes. secondary school degrees should work well for this predictors of final educational attainment, skills, Nevertheless, the exercise since they are good and wages. We picked the three education groups for the U.S. so that they are of roughly comparable size to the groups. The German data are the cell for the highest employment who have rates skill available for the group and wages in For Germany, five-year age groups. the age bracket 25-29, because for this cell yet to complete university 20 age-by-education same we were German We dropped worried that might be contaminated by including students and be working part time. This provides a total of cells. we calculated the average log wage for each cell using the 1979 ^^These are taken from Statistisches Bundesamt, Fachserie 1: Bevolkerung und Reihe 4.1.2: Beruf, Ausbildung, und Arbeitsbedingungen der EnA/erbstatigen (Wiesbaden). Enwerbstatigkeit, 13 and 1991 "Qualifications sample (about 25,000 observations) we Therefore, is limited to civilians who encompasses Germany's still mean to avoid large rise any impact Lemieux found long log The figures reveal a pattern that for the U.S. wage growth and and France. the change against the 1980-81 average log wage cells wage First, in is The change in Using data of unification, but this German men similar to in Figures 2 and what Card, Kramarz and the employment-population rate for each cell Real wages declined between 1979-80 and 1990-91, and grew profile in the U.S. wage. The sample consider the U.S. Figure 2 plots decade- for the cell. consistent with the well-documented rise a large unemployment. in Results are presented graphically for American and 3, respectively. log hourly is employed persons. are employed outside of apprenticeships. 1970s and early 1990s allows us for the late period that consists exclusively of only use this data set to calculate the German The QaC and Careers Survey" (QaC) surveys. in for the highest the education lowest for the ones. This is premium and age-earnings the employment rate, on the other hand, is only weakly correlated with the base wage. The the wage results on wages structure did not slight tightening of the Institutionally rigid and the initial relationship for in Figure 3 are noisier, but change very much between 1979 and 1991. wage structure wages may wage German men seemed well explain the level of the cell. between the change in to it is clear that If anything, a have taken place during this period. weak correlation between wage growth Turning to employment changes, there is no the employment-to-population rate for the age- education cells and the base wage, despite the fact that wages appear rigid. If demand 14 fell for less skilled the lowest wage workers, The summary regressions in change in wage in well as for little wage the log change or pattern of results evident men. Indeed, contrary wage In in the employment the base period. Separate models were estimated for in to the levels level than in the wage rigidity story, for cell in in both the the base period. men and women employment rate of the cross-country relative workers" because the distribution of human But this why there Germany and France between look at unemployment rates capital explanation cannot explain slope the wrong way, or A some explanation for the rise of the in is for different across the workforce why Bell), either groups may vary of across the cross-country relationships often evidently no relationship within countries such as the decline in evidence cited employment and wage in levels. support of the relative-wage European unemployment shows it to inflexibility be less than compelling. For example, Siebert (1997) writes: A the statistical wages and cross-country data between the development of relative aggregate unemployment rates or countries. as and the evidence (including Nickell and Lindbeck (1996) correctly points out that "we should not expect a close in women Germany. commenting on some correlation on rate men and women. Figures 2 and 3 appears to hold for U.S. displays a steeper relationship between the change initial relationship. Table 2 reinforce these observations. This table These regressions are weighted by the employment The general among expect to find employment declining most groups; instead, there appears to be reports regressions of the the log we would country which institutionally prohibits flexible wages at the lower end can 15 have a low percentage of employment in low-paid jobs. This is exactly what can be observed. Defining low-paid workers as those who earn less than two-thirds of the median wage, the percentage of lowpaid workers in total employment varies noticeably with the dispersion of earnings, from 5.2 percent in Sweden to 25 percent in the U.S. (Belgium 7.2, Netherlands 11.9, Italy 12.5, Germany 13.3, France 13.3, United Kingdom 19.6; OECD 1996, Table 3.2). be expected A problem with this to comparison wage one would expect if hypothetically that wage floors wage in some the is that the observed empirical pattern had no floor raise effect countries with higher relevant question is wage would have a lower countries that Siebert of the ladder lists, there is a and the incidence chopped to just off, is or fraction of "low-paid jobs". striking is among But the were they simply elevated? For the slight positive correlation between the employment- of low-paid work.^^ high school dropouts among women. One would expect rates for poorly educated youth to that associated with lower employment; workers without an apprenticeship qualification or higher degree it suppose below the median Blau and Kahn (1997) find that the employment-to-population rate higher than this, employment. Then one would expect whether the wage compression were the bottom rungs to-population rate floors also exactly what on employment. To see low-wage workers' earnings countries, without reducing their is in the U.S. The in in the U.S. than Germany difference labor market inflexibility to be higher among young is is much especially cause employment Germany. ^^The correlation between the employment-population rate using 1994 BLS data and the fraction of low-paid workers reported by Siebert is 0.37, with a p-value of 0.42. Belgium is excluded from this calculation because the BLS lacks data on Belgium. The OECD (1996) analysis cited above also finds insignificant and often wrong-signed correlations for a larger set of countries. 16 If the simple version of employment growth across appropriate. rigidities, We throughout the distribution. market there rigidities is Europe. in may well has trouble explaining the pattern perhaps a more complicated possibly because of unions. -- firing restrictions, do not want that, is it large effects on or inhibit is wage Moreover, job growth of the But, unfortunately, employment problems in not clear theoretically that firing costs should lower average as expected, more employment security employment employment. much Bertola, 1992). Analyzing data for ten cyclical fluctuations in may of dismiss these other forms of labor to scant direct evidence that they account for Furthermore, model apply not only to the bottom of the such as because they may have employment (see found floors and top as structure, but to the middle rigidities groups, skill wage For example, other forms of institutional wage employment. unemployment and He OECD countries, Bertola (1990) associated with a lower amplitude is did not find a clear relationship firing restrictions, between however. Anderson (1993), using data on the experience rating of the U.S. unemployment insurance system, finds that firms hand, have higher average employment when they face higher some layoff costs. studies do find that job security legislation affects 1994, chapter 6 and Lazear, 1990). test the effect of By their nature, it is the other employment (see OECD, hard to identify and empirically these institutions on employment. Finally, there is the puzzle of that in the U.S. for decades, if why the unemployment rate labor market rigidities are so in Europe was critical. that in the U.S. If a more flexible labor market is well For example, 5 of the 21 years between 1975 and 1996 did the unemployment rate exceed On in below in only West Germany responsible for the recent low 17 unemployment rate in that prevailed in the Each matter much in rigid; the past because there were no adverse labor market (2) demand shocks; of these three reconciliations may have some merit, but they also have For example, which institutions changed, and what evidence links these limitations. suffer There are three possible the not too distant past? in take a long time to take effect after an adverse shock. (3) rigidities changes U.S. European labor markets have become more reconciliations: (1) rigidities didn't the U.S., what accounts for the relatively high unemployment rates employment growth? Furthermore, to adverse shocks earlier in the it is hard to imagine that countries did not post-war period that would have made their rigidities more apparent. Whether the increase in in wage Europe represent two sides suspect that rising wage dispersion of the inequality in same in the U.S. and the rise coin the U.S. is is in an open question. related to a decline unskilled workers relative to skilled workers, the evidence that the decline in France and Germany seems have to little is concentrated among the unskilled is us that more must be going on than just labor market doubt that labor market rigidities unemployment in in Although we demand for employment surprisingly shallow. rigidities -- although are an impediment to job growth in It we some countries. III. Observations on U.S. Job Growth and Population Growth How does population? the U.S. economy manage to provide so many jobs for a growing Several examples that are described below suggest that the U.S. has 18 managed change in to absorb population growth real fairly inelastic, than is growth wage so it observed. is is levels. employment with relatively little Moreover, much evidence suggests that labor unclear The into why below suggest We do not profess as much a mystery as a miracle. labor market equilibrates (or whether it market adjustments take place with little that U.S. to demand is wages by more population injections do not reduce conflicting observations systematic employment understand how the equilibrates), but recognizing that large labor wage adjustment is an important step in understanding the U.S. employment miracle. Examples of Employment and Wage Adjustments Population Shocks to Immigration provides a classic population supply shock that would be expected to influence wages. Yet careful analyses of four large episodes of immigration boatlift to Miami; the repatriation of Algerian French workers to southern France; the migration of workers from Angola and colonies; the Mariel -- Mozambique and the recent mass migration of to Portugal after Portugal lost from the former Soviet Union to Israel reach the surprising conclusion that large immigrant flows did not depress the natives (see Card, 1990; Hunt (1992); Carrington and De The swings in in Ireland, have not been accompanied by labor supply brought about by the another example of large employment shifts with -- all wages of Lima, 1996; and Friedberg (1996)). Olson (1996) also notes that large population declines as was the case its due real to outmigration, wage such increases. baby boom and baby bust provide seemingly little consequence for wages. 19 The early work on the absorption baby boom cohort of the large cohort of workers experienced in the U.S. found that this modest wage reductions when they entered the labor market, but faster earnings growth thereafter which diminished their losses (see, for example, Welch, 1979). Subsequent research by Berger (1985) found reduction for the baby cohort tended to be larger and in the experience-earnings profile call for the entry of the smaller baby bust cohort decline in earnings earnings profile to for young workers; become much the late 1980s in If Card and Lemieux, 1996). Moreover, up this pattern Notably, was accompanied by a sharp cohort size were for the wage But recent trends phenomenon has caused this expected the cross-sectional experience-earnings bid persistent. a re-examination of this conclusion. steeper. because wages would have been more that the profile to critical, become the experience- one would have flatter in this period newly entering baby bust cohorts (see seems to be appearing worldwide (see Blanchflower and Freeman, 1997). Another example concerns female employment earnings gap between 1994, the fraction of to 56.2% (while the male earnings relative ratio men and women has women age 20 and employment rate for the U.S., which has grown while the narrowed. For example, between 1979 and over who were employed men declined by 3.9 points), and the female-to- increased from .63 to wage and employment in .73.^" trends to a One demand increased from 47.7% might be tempted to attribute these shift in favor of women, but there is ^''These statistics are from Report on the American Workforce U.S. Department of Labor, Washington, D.C. 1995. The earnings data are for women age 25 and over, and . pertain to 1980 and 1994. 20 reason to doubt higher is wage this explanation; in tine groups, and women women were that, in the past, It is well relative known Table 3 presents that discriminated against rate real in An women wages are only in and a time trend toward alternative explanation A the labor market. well as related of to liave siiifted changes in decline in social norms, to rise. mildly pro-cyclical recent evidence that reinforces this point. regressions of the annual change unemployment women, as wage and employment aggregate some demand appears tend to earn less than men. labor market discrimination against caused both the 1980s, the log of the real wage on for several different measures The the in the U.S.''^ table reports change of real in the wages and over various time periods. These results suggest that the weak responsiveness of real wages to the state of the business cycle has Although the aggregate wage data may be become even weaker biased by changes in since the 1970s.^^ the composition of the workforce over the cycle, the employment cost index (EC!) data attempt to adjust for composition changes by holding the job mix constant. Notably, the extent of pro-cyclical wage movements are even smaller with the ECl compensation measure.^^ ^^The literature on the cyclicality of real wages began with Dunlop (1938). For a thorough survey, see Abraham and Haltiwanger (1995). ^^The price index used to deflate these series is the CPI-W. Abraham and Haltiwanger report that wages tend to be more procyclical when they are deflated by this price index than by the Producer Price Index (PPI). ^^See Solon, Barsky and Parker (1994) for evidence from longitudinal data that in the composition of the workforce over the business cycle masks greater changes procyclical movements in real wages. 21 The preceding observations is highly elastic direct a shift in be interpreted as evidence population can be employed with evidence on employment demand emphasized elasticities, that little employment demand change however, suggest a For example, the center of the range of Marshallian of elasticity. labor -- migint Hamermesh's (1993) review in demand relatively inelastic, described above resulted in it of the literature is seems anomalous in wages. The fairly demand elasticities -.50.''^ Thus, with around that the large population of large intertemporal labor supply responses. This too microeconometric evidence (see Killingsworth, 1983 IV. swings employment gains without reducing wages. Others, of course, interpret the weakly pro-cyclical tendency of real evidence low level for is wages as contradicted by much a review). Theoretical Explanations A great deal of labor market adjustment systematic real demand shifts, wage movements. while in others it is wage changes appear only weakly While labor market rigidities In related to seems to take place without cases, the adjustment is associated with shifts; yet in either employment movements. How can part of the explanation for inflexible to explain population changes at seemingly fixed wages. comes from the U.S. associated with supply may be themselves they are hard pressed some in why employment We scenario this be? wages, by often rises or falls with speculate below that recognizing the employment effects of minimum wage increases, at least in the U.S. A variety of evidence has found only small or undetectable movements in employment associated with minimum wage increases (see Card and Krueger, 1995, and Brown, Gilroy and Kohen, 1982). ^^Further evidence the very small 22 role of certain product observed empirical market restrictions in addition to economy course, is as population A problem is doubled the capital stock and other inputs An proportion to population; namely, "entrepreneurial talent." bring about an equal proportionate increase in number the of is that may rise may roughly influx of population people with not skills in may capable becoming an employer. This point can be made clear in a modified version of Lucas's (1978) model of employment and management choice. In Lucas's original model, a fixed population chooses between supplying labor as an employee equally productive talent or on Consequently, that if all wages. First We In All rigid in is a distribution of entrepreneurial Lucas's model, there are no restrictions on entry into output resources are wages are more Europe. or as an entrepreneur. All people are they work as laborers, while there across people. ^^ management in wage with this interpretation, of But one often-overlooked form of inputs necessarily double. of can help explain the population at a fixed real displays constant returns to scale. that rigidity facts. One reason why employment may grow with the wage fully is sold at a constant price, taken as the numeraire. employed. Europe and add these two constraints that A number new to the of commenters have noted entrepreneurs are more constrained model. consider the effects of a constraint on wages, such as a wage floor. As in the standard model, firms would choose to hire less labor to equate the marginal product ^^The idea of modelling a distribution of entrepreneurial talent goes back to at least J.-B. Say (see Palmer, 1997, Chapter 4). The Lucas model can also be thought of as a special case of the Roy model. 23 wage of labor with the binding uniformly across the labor force. expected wage managers now be -- queue because of that demand a wage (MGI) in growth to a recent study of in than one, the and this will In - managers would workers in the process. a series of cross-country regulations, rather than labor market rigidities productivity MGI France, distributed draw marginal emphasizes product market employment and Germany and for labor is less to release their zoning laws, and restrictions on employers as the main barriers is floor, consider the employer side of the market. Institute unemployment the least talented In particular, causing them for work, McKinsey Global example, assume the elasticity of into the for-hire workforce. Now restrictive If of laborers will rise enticed to studies, We floor. in many sectors. (1997) concludes, "In all For the sectors studied, the main barriers to higher productivity have been product market regulations that and global competition limit fair constraint on employers, permitted to become an as does the wage floor. suppose that If number the no more than a proportion The entrepreneur. of restriction would be the when a -- is first In equilibrium, like to of new firms -- is curtailed least their own firms. is countries, some potential managerial talent (and smallest for labor is more for labor inelastic adjustment by regulation. there are unemployed resources open up of the population restricted, then a binding constraint on entrepreneurs because one margin namely the formation would is become employees. The demand to of capturing the a probably varies across employers employers become employees. Employers with the firms) As a simple way ...." in this model, and An exogenous increase in some workers population would be 24 associated with a proportionate increase the proportion of the population that If, however, the grow in employment and unemployment, as long as permitted to is become an entrepreneur on entrepreneurs constrains the number restriction population. rises, Intuitively, and employment rise will but entrepreneurs to unemployment less than proportionately with population, then the the population of if the number cannot of firms rate will rise as than proportionately with less the constraint on the employer-side of the market intense with population growth constant. is becomes more rise in proportion with population. More generally, the demand curve for labor will become more constraints on capital or other factors of production that This result demand labor a manifestation of Marshall's for labor declines Appendix). have the is if in will there are demand law of derived is -- the elasticity of inelastic (see Hicks, 1932, the capital market or on entrepreneurs can obviously making the supply demand curve if the supply of these factors. limit the supply of capital to a firm Certain constraints effect of third inelastic of be constrained these resources inelastic. relative to a situation in In this situation, which capital is the elastically supplied. Figure 4 illustrates the effect of a curve. The unconstrained respectively. effective The wage labor demand curve cause the demand curve to floor and constraints on the labor demand demand and supply curves fixed at w-bar. is demand curve (denoted the effective wage The are given by become more and SS, constraint on entrepreneurs causes the We have drawn D'D') to rotate clockwise, as depicted. quite steep, to DD emphasize inelastic. that product market constraints Notice that simply lowering the wage 25 floor will have a modest impact on employment because the demand constraint causes the effective demand the effective demand (as become more curve to curve to the right if inelastic. An increase population will shift the population increase relaxes the constraint employment the model with heterogeneous entrepreneurs), causing in in to rise but not wages. This model also for we example, constraint is may help suspect that the wage constraint demand curve it demand closer to the unconstrained firms are less constrained Germany cross-country comparisons. in is to shift out much more country's difficulty in in (1 level.^° The demand curve. in of the for enough capital, labor is so effective labor demand 20| is demand we up start expect the effective By contrast, in when population expands. of output is in fixed is constrained Figure 4. In in the the Barro above the equilibrium is therefore determined by the product hired to meet the constrained product market of labor workers because they cannot model. Allowing the U.S. and the features as the model demanded Germany, Furthermore, because example, the product price quantity of output Just same to businesses, which might contribute to the which the quantity in demand. Although the marginal product hire additional new providing additional jobs 971 ) model, curve. in proportion with population growth. difficult to start Notice also that a model and Grossman lower the U.S., as population grows about aggregate would have many is Compared exceeds the wage, employers do not sell their output. Barro and Grossman perfectly inelastic with respect to the for capital-labor substitution will introduce some wage ignore in their elasticity to the effective For a review of non-Walrasian models, see Benassy (1986). 26 demand the but curve, unconstrained case because there cause the demand curve if model, however, this the equilibrium level The is is no scale effect. if will still be less than An increase demand in is reason for the An unsatisfactory product price to be fixed above is to emphasize that rigidities may arise from areas outside the labor market, but have an important impact on labor demand. number may be partially relaxed companies start-up of as the population grows. or capital many starting countries. new constrain wage The U.S. is employment by making floors With less restrictive than enterprises and bringing make little new products effective demand effective labor supply elastic direct Moreover, Restrictions on the market imperfections or product market regulations or restrictive zoning rules or restrictive store hours In demand unspecified. point of this discussion these restrictions the the product market rises with rise to satisfy the larger population. that the in population would in population increases because of immigration, the goods and services may also aspect of demand to shift to the right the population. For example, for labor of elasticity in evidence on the importance many may depress employment countries to market.^^ when comes to barriers may same way that These relatively inelastic, the it sticky-wage models. of product market constraints, at this stage our theoretical predictions should be regarded largely as conjectures (hence our title). The impact ^^Even the of product market constraints on the however, demand for labor should be a a reduction in entrepreneurs' personal income tax rates induces them to hire more workers. A plausible interpretation of this finding is that entrepreneurs are liquidity constrained, and finance in U.S., Carroll additional expansions with their tax windfalls. et al. (1996) find that 27 priority for future environments and Identifying cross-country differences research. for specific industries role of trade associations would be one route for future -- -- and work in product market including the competitive structure of the market linking in this these differences to employment growth area to take. 28 V. Conclusion The U.S. has been very successful at providing jobs for our growing population. A great deal of employment adjustment seems movement. The empirical observations and demand-side constraints are important. (e.g., restrictions demand the demand greater in and The for labor. many European little relax for labor while inclination to programs) and in its some of the demand-side population become an is likely to in constraints, wages remain supply increases and increase the pool of entrepreneur, thereby increasing constraints on the demand-side of the market countries than wage paper suggest in this social insurance real on entrepreneurs and product market regimes) roughly constant. For example, an increase individuals with the talent and floors A growing population may help thereby increasing the take place with relatively theoretical conjectures wage that both supply-side constraints (e.g., to the U.S., and may may be much prevent employment from rising with population. Much policy discussion of the market. A has focused only on the supply side neglected concern market regulations and institutions and become more is may that restrictions distort labor flexibility would generate more wage dispersion but possibly Just as sharpening one blade of a scissor blades are be less dull, reducing effective than is wages will scenario, providing additional not greatly little additional wage employment. enhance performance without relaxing constraints on the commonly expected. rigidities) demand, causing the labor demand shift in In this wage on entrepreneurs and product curve to inelastic. (e.g., if both demand curve may 29 References Abraham, Katharine and John Haltiwanger. 1995. "Real Wages and the Business Cycle." Journal of Economic Literature 33, no. 3, pp. 1215-64. Anderson, Patricia. 1993. "Linear Adjustment Costs and Seasonal Labor Demand: Evidence from Retail Trade Firms," Quarterly Journal of Economics 108, p. 1015-1042. . and Herschel Grossman. "A General Disequilibrium Model Employment." American Economic Review 61, pp. 82-93. Barro, Robert of Income and , 1986. Macroeconomics: Benassy, Jean-Pascal. Approach New . York: Bertola, Guiseppe. 1990. "Job Security, Review . An Introduction to the Non-Walrasian The Academic Press. Employment, and Wages," European Economic 34, p. 851-879. Berger, Mark. 1985. "The Effect of Cohort Size on Earnings Growth: A Reexamination Economv ,93. no. 3 (June), pp. 561-573. of the Evidence," Journal of Political Turnover Costs and Average Labor Demand," Journal Labor Economics 10, 389-411. Bertola, Guiseppe. 1992. "Labor of , Blanchflower, David and Richard Freeman. OECD," mimeo., presented Advanced Countries. the in at 1997. "Analysis of Youth Labor Markets in NBER Conference on Unemployment and Employment and Lawrence Kahn. 1997. "Gender and Youth Employment Outcomes: The US and West Germany, 1984-91," NBER Working Paper No. 6078, Cambridge, MA. Blau, Francine, Brown, Charles, Curtis Gilroy and Andrew Kohen. 1983. "Time Series Evidence on the Effect of the Minimum Wage on Youth Employment and Unemployment." Journal of Human Resources 18, pp. 3-31. Calmfors, Lars and Anders Forslund. 1991. Market Policies: "Real- Wage Determination The Swedish Experience," The Economic Journal 1 01 , and Labour (September), pp. 1130-48. Card, David, Francis Kramarz and Structure of France." Thomas Lemieux. Wages and Employment: A Comparison NBER 1996. "Changes in of the United States, Working Paper No. 5487, Cambridge, MA. the Relative Canada, and 30 Card, David and Thomas Lemieux. 1996. "Adapting to Circumstances: The Evolution of Work, School, and Living Arrangements Among North American Youth," mimec, Princeton University. Card, David and Alan Krueger. 1995. Myth and Measurement: the Minimum Wage Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. The New Economics of . "The Impact of the Mariel Card, David. 1990. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 43, Africa De on the Miami Labor Market." no. 2 (January), pp. 245-47. , Carrington, William and Pedro Boatlift 1996. "The Impact of 1970s Repatriates from and Labor Relations Review 49, no.2 Lima. on the Portugese Labor Market." Industrial , (January), pp. 330-347. Douglas Holtz-Eakin, Mark Rider, and Harvey Rosen. Carroll, Robert, Taxes and Entrepreneurs' Use of Labor," Princeton Paper No. 373 (December), Princeton, NJ. Dunlop, John. pp. 413-34. 1 Edin, Per-Anders, Wage Movement 938. "The Inequality in and Real and New 1996. . 191, "Unemployment and 1996. "An Evaluation of the Swedish Active Labor and Received Wisdom," forthcoming R. Topel, (eds.). Working Money Wages," Economic Journal Anders Harkman and Bertil Holmlund. Sweden," mimeo, Uppsala University. Forslund, Anders and Alan Krueger. Market Policy: of 1996. "Income Industrial Relations Section The Welfare State in in R. Freeman, B. Swedenborg, Transition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press). Friedberg, Rachel. 1996. mimeo.. Providence, Rl, "The Impact Brown of Mass Migration on the Israeli Labor Market," University. Godbout, Todd. 1993. "Employment Change and Sectoral Distribution 1970-90". Monthly Labor Review (October), pp. 3-20. Hamermesh, Daniel. 1993. Labor Hicks, John. 1932. Hunt, Jennifer. Labor Market." The Theory Demand of in 10 Countries, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press). Wages (New York: Macmillan Press). 1992. "The Impact of the 1962 Repatriates from Algeria on the French Industrial and Labor Relations Review 45, no. 3 (April), pp. 556-72. 1995. "The Effect of Unemployment Compensation on Unemployment Germany." Journal of Labor Economics 13, no. 1, pp. 88-120. Hunt, Jennifer. Duration in , 31 Lawrence and Bruce Meyer. 1990. "Unemployment Insurance, Recall Expectations and Unemployment Outcomes." Quarterly Journal of Economics 104, pp. 973-1002. Katz, . Killingsworth, Mark. 1983. Labor Supply Cambridge, England: Cambridge University . Press. Krugman, Paul. 1994. "Past and Prospective Causes of High Unemployment," Reducing Unemployment: Current Issues and Policy Options A Symposium Sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, August 25-27, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, 1994, pp. . 49-80. Stephen Nickell, and Richard Jackman. 1991. Unemployment: Macroeconomic Performance and the Labor Market (Oxford: Oxford University Press). Richard, Layard, Lazear, Edward. 1990. "Job Security Provisions and Employment," Quarterly Journal of Economics 105, Levine, pp. 699-726. 1993. Phillip. Unemployed." Industrial "Spillover Effects Between the Insured and Uninsured and Labor Relations Review 47, no. 1, (October), pp. 73-86. . Lindbeck, Assar. 1996. "The West European Employment Problem." Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv (Review of World Economics), pp. 609-637. Lucas, Robert. Economics "On The Size Distribution 2 (Autumn), pp. 508-523. 1978. 9. no. of Business Firms," Bell Journal of Meyer, Bruce. 1989. "A Quasi Experimental Approach to the Effects of Unemployment Insurance," NBER Working Paper No. 3159, Cambridge, MA. Meyer, Bruce D. 1995. "Lessons from the U.S. Unemployment Insurance Experiments," Journal of Economic Literature 33, March 1995, pp. 91-131. . Stephen and Brian Nickell, Unemployment Across the Bell. 1995. "The Collapse OECD." Oxford Review of in Demand Economic for the Unskilled and Policy 11, pp. 40-62. 1996. "Changes in the Distribution of Wages and Unemployment in OECD Countries." American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings 82 (2), pp. 302-308. . Olson, Mancur. 1996. "Big Bills Left on the Sidewalk: Why Some Nations are Rich, and Others Poor." Journal of Economic Perspectives 10, no. 2, pp. 3-24. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. 1996. Employment Outlook (July), Paris, France. 32 1994. . The Adjustment Potential L Palmer, OECD of Jobs Study the Labor Market. 1997. J.-B. Say: Evidence and Explanations. . Part II: The Paris, France. An Economist in Troubled Times (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press). "Labor Market Rigidities -- At the Root of Unemployment Forthcoming, Journal of Economic Perspectives Siebert, Horst. Europe." 1997. in . 1985. Solon, Gary. "Work Incentive Effects of Taxing Unemployment Benefits," Econometrica 53, pp. 295-306. , Solon, Gary, Robert Barsky, and Jonathan Parker. 1994. "Measuring the Cyclicality of Real Wages: How Important Is Composition Bias?" Quarterly Journal of Economics 109. February, pp. 1-26. 1979. "Effects of Cohort Size on Earnings: The Baby Boom Babies' Financial Bust." Journal of Political Economy 87, no.5, October, S65-S98. Welch, Finis. Table 1: Determinants of Cross-Country Employment Growth, 1959 - 95 Dependent Variable: Log Employment - Log 1.29 Population (4) (3) (2) (1) Women Men All ~ - (5) 1.21 (6) (7) - " 1.60 .95 -.52 -.10 .43 -.98 -.66 1.88 (+ 100) (.05) (.04) (.09) (.04) (.04) (.08) (.07) Yearx 1.01 .40 .81 .27 (.13) (.06) (.12) (.05) -.73 -.18 -.47 -.09 (.13) (.06) (.12) (.05) Year U.S. (+ (9) - (.07) (.03) (.03) (8) 1.09 (.19) .07 .49 (.09) (.17) .41 (.12) 100) Yearx Germany -1.27 -.37 (.20) (.13) Yes Yes (-^100) Yes Country Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Dummies Log Population Interacted with: 1.28 U.S. Canada Australia Japan 1.17 (.06) (.05) (.11) 1.25 1.10 1.69 (.05) (.04) (.08) .97 .90 (.05) (.05) Germany Italy Netherlands R2 (.13) .62 .60 .86 (.98) (.09) (.20) .47 .73 .23 (.14) (.10) (.31) .40 .68 .51 (.12) (.10) (.22) Notes: Sample size .999 is (.18) 1.69 .80 (.15) (.15) .69 .60 (.23) (.18) .999 351 for Columns 2.70 .79 (.09) 1.05 .994 .49 (.06) (.10) U.K. (.09) (.07) 1.27 Sweden 1.32 1.27 .90 France 1.58 .995 1 - .999 (.28) 1.43 (.46) .986 .999 3 and 343 for Columns 4 - 9. .995 .999 Table 2: Regression of Change in Log Wage or Employment-Population Rate on Base Wage, United States and Germany Women Men Independent A mean A empi. A mean A empl. variables In(wage) rate In(wage) rate 1. ln(1 979 wage) .393 .075 .309 .092 (.038) (.018) (.056) (.038) 2. ln(1 979-80 wage) U.S. (20 groups) -.140 (.084) Germany (20 groups) .008 -.104 -.069 (.018) (.066) (.053) Table 3: Cyclicality of Real Wages, Various Wage Change in Unemployment Rate Employment Cost A. Series: 1981:Q1 - 1997:Q1 Series and Time Periods Trend n -.07 -.09 65 (.12) (.03) Index; Quarterly Data Production/Nonsupervisory Workers (CES); Annual Data B. Series: 1948-1996 1948-1980 -.44 -.09 (.20) (.02) -.46 -.14 (.25) (.03) -.19 -.00 (.21) (.04) 49 33 " 1981 - 1996 C. Series: 1965:M1 1981:M1 - - Production/Nonsupervisory Workers (CES); Monthly Data 1997:M3 1997:M3 1970:M1 -1979:M12 1980:M1 1990:M1 - - 16 1989:M12 1997:M3 -.66 -.07 (.08) (.01) -.15 -.00 (.06) (.01) -1.12 -.48 (.14) (.06) -.24 .16 (.13) (.06) -.05 .28 - Continued 387 195 120 120 87 Table D. 3: Continued Hourly Earnings by Decile from Outgoing Rotation Groups of Current Population Survey, 1973-96 Percentile 10th 50th 90th Change in Unemplovment Rate Min. Wage Increase Trend n 23 -.95 .034 .09 (.48) (.014) (.10) .04 -.009 -.06 (.24) (.007) (.05) -.36 -.006 -.04 (.26) (.008) (.05) Notes: Reported coefficients are from regressions of the annual change 23 23 in the log real wage (deflated by CPI-W) on the annual change in the unemployment rate (divided by 100), a linear time trend (year divided by 100), and an intercept. In panel D, a variable indicating whether the minimum wage increased that year is also included; this variable equals one if the minimum wage increased on January 1st of the year, and the fraction of the year in which the higher minimum wage was in effect for years in which the minimum increased after January 1st. The dependent variable used in Panel D was provided by Jared Bernstein; all other wage data are from the BLS. , ; Figure Change in Log Employment .2 vs. 1 Change in Log Population, 1964-95 2 2 2 '^:^^^^ ? c cu E o 2 1 .1 - B 10 10 Be 1 ^^ jl 1 1^ jn^ 10 2 2 /I O D1 C - fO %^^R)"6' c fD O) I in -.1 - i .05 i .15 .1 5-Yean Change in Log Population Country codes: U.S.=1; Canada=2; Australia=3 Japan=4 France=5; Germany=6; Italy=7; Netherlands=8 Sweden=9; UK=10. ; ; Source: BLS International Comparisons Program. en CNJ QJ -M fD CO CZ d UJ _CNJ CNJ QJ o cn cn cn cn CU CD c I C^ o OvJ QJ CJ1 cn QJ Q- "a en ro fD o -CM -rH Ll cn QJ c QJ fD QJ CD CD ru fD cn cn cn cn o QJ cn QJ cz CD cn c: fD JZ u o 00 D sa^BH ;uaiuAoiduJ3 'sbBbm ui aBueqo MIT LIBRARIES 3 9080 01444 4050 -m cu CD CD cr o: en CD B o C) en CD en CNJ en c CD CL en I on _co ^^ CJ CD O CD cm o zi CD c: ro •r-l j_ „ cz CD en CD :^ cji c: ID C\J CD CD (3n o C -rH CD CD £Z CD CD (JJ CD en CD rsj o D sa^ey ;u3LuAoiclaJ3 'saSeM ut aBuEL|3 c= CD CD OS O O Q 03 72 n Date Due