1 si

advertisement

1

si

>CHU^

^

*

5 (iSBSAS^j §

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011 with funding from

Boston Library Consortium

Member

Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/onillsofadjustmeOOcaba

DEWEY J

working paper

department

of economics

ON THE ILLS OF ADJUSTMENT

Richardo

J.

Mohamad

95-21

Caballero

L.

Hammour

Jul.

1995

massachusetts

institute of

technology

50 memorial drive

cam bridge, mass. 02139

ON THE ILLS OF ADJUSTMENT

Richardo

J.

Mohamad

95-21

Caballero

L.

Hammour

Jul.

1995

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE

NOV

1 4 1995

UDP«?^iuO

95-21

On

Ricardo

the

of

Ills

Mohamad

Caballero

J.

Adjustment

This version: July

17,

L.

Hammoui*

1995

Abstract

We

analyze market impediments to the process of structural adjustment.

on incomplete-contract

inefficiencies in the transactions

We

focus

between workers and firms that

render the quasi-rents from "specific" investment appropriable. During adjustment, the

result

is

a depressed rate of creation of the new productive structure and excessive de-

struction of the old one, leading to an

weakens the incentives

tive structure.

An

employment

for extensive restructuring,

crisis.

and

Moreover, appropriability

results in

a

contracting one. In contrast, the

common

effective "synchronizer" of creation

also reducing

produc-

adequate managed-adjustment program ought to combine vigorous

creation incentives in the expanding sector with measures to support

by

"sclerotic"

employment

in the

prescription of gradualism does not act as an

and destruction,

an already depressed creation

for

it

can only reduce destruction

rate.

Introduction

1

1.1

Adjustment Crises

The need

to restructure the economy's productive system

and reallocate

factors

is

common

to a variety of experiences in the developing world, as countries face changing external

opportunities or attempt to liberalize their economic system. Such adjustment episodes are

often times of

crisis.

Those

crises

have important financial and

political

dimensions but,

MTT and NBER and CEPREMAP. An earlier version of this paper was presented at

Seventh Annual Interamerican Seminar on Economics in Mexico City, November 1994. We

are grateful for the comments we received at the conference, and from Olivier Blanchard, Manuel Santos,

Rodrigo Valdes and seminar participants at CEPREMAP (Paris), IDEI (Toulouse), and the Tinbergen

Institute (Amsterdam). We also thank Rodrigo Valdes for excellent research assistance. Ricardo Caballero

thanks the National Science and Alfred P. Sloan foundations for their financial support. Part of this paper

was written while Ricardo Caballero was a Visiting Scholar at the IMF.

'Respectively,

the

NBER

at a

more fundamental

place in an orderly

Adjustment

bears the

full

and

level,

they can be the

efficient

crises are generally characterized

in the

new

of a failure of restructuring to take

manner.

burden of the shock and

and investment

symptom

by an existing productive structure that

faces extensive destruction, while the

structure remains excessively timid. In the

pace of creation

common

experience

of countries subject to adverse external shocks, for example, sharp contractions in non-

tradables are typically only followed slowly by growth in the tradables sector, giving rise

to an acute

employment problem. Brisk trade

lead to such a

crisis,

liberalization,

with an immediate contractionary

effect

it is

often feared,

on importables that

counter-balanced by the gradual growth in exportables. Another example

is

may

is

also

hardly

provided by

the recent experience of reforming economies in Eastern Europe, where the immediate collapse of the old state sector

new

was typically only accompanied by a sluggish emergence of the

private sector ultimately intended to replace

As a consequence

ation,

of the

wedge between sharp immediate destruction and sluggish

an employment problem develops.

Many

tracting sectors find themselves either in overt

much

less attractive activity in

employment

1.2

A

We

focus

crisis

it.

workers

who

cre-

lose their jobs in the con-

unemployment or being forced to take up

the informal sector.

When

the state sector

is

involved, the

often leads to a surge in idle public-sector jobs.

Micro-Structural Approach

on supply-side aspects of adjustment, commonly viewed

the productive structure

as the process

by which

— the sectoral composition of output and allocation of

factor proportions

use — adapts to a new environment.

factors,

the techniques and relative

in

Because of the embodiment of technology in

capital, skills

1

and the organization of work,

restructuring usually necessitates a reallocation of factors of production, which involves the

1

See, e.g., Mussa (1978)

aspects of adjustment.

Our

and Neary (1982)

for seminal contributions to the analysis of the supply-side

general notion of adjustment abstracts away from the specifics of the environment change that gives

it.

We do not address, for example, the exchange rate and stabilization dimensions of external

adjustment in developing countries; the sequencing of reforms in trade liberalization; or privatization and

the behavior of the state sector in the Eastern-European reform experience. One aspect of our approach

that makes it less directly applicable to the Eastern European case is the profit-maximizing behavior we

assume for the contracting sector, which does not capture the nature of decision-making at the level of state

enterprise. For analyses that address this issue, see, e.g., Chadha, Coricelli and Krajnyak (1993), Aghion

and Blanchard (1993) and references therein. See also Shimer (1995) and Atkeson and Kehoe (1993) for,

respectively, search and moral hazard models of reform sharing several of the positive implications of our

model.

rise to

— with

destruction of existing production units that developed under the old environment

the accompanying loss of jobs and scrapping of capital

better adapted to the

We

new

— and the creation of other units

one.

analyze market impediments to the restructuring process that lead to adjustment

A

crises.

very promising approach, we believe,

is

to build our macro-analysis

micro-structure that characterizes exchange in factor markets.

We

on the

focus on the general

incomplete-contracts problem of appropriability in labor and capital market transactions,

which captures the essence of a broad variety of practical obstacles to well-functioning

Appropriability has been identified as a principal dimension of Coasian (1937)

markets.

transaction description in the

New

Institutional

and 1985; Klein, Crawford, and Alchian,

problem

ment

1978; Hart

arises in the joint use of capital

and labor

required. In the absence of complete

is

Economics

and Moore, 1988). In our context, the

is

who may engage

Hammour

appropriability for the cyclical

characteristics of adjustment crises to appropriability problems,

specificity

in opportunistic

behavior of investment, job flows, unemployment, and wages. In this paper,

in times

specific invest-

and binding contracts, investment

sunk (Grout, 1984). In Caballero and

show the general-equilibrium implications of

when

for production,

gives rise to quasi-rents that are appropriable by workers,

behavior once investment

literature (Williamson, 1975

(1994),

we

and long-run

we

trace major

which gain particular bite

— such as adjustment episodes — when high rates of investment and job creation

are required.

It is

to

important to emphasize the prevalence of the appropriability problem, which applies

much more than simply job-specific human capital. There are a number of levels

capital

and labor

political level

interact

— each

put to

level,

its

level imprinting its

At the

may have

is

specific training

level,

which

the aggregate

investment. Investment

its

value

if

At the individual worker-firm

and organizational investment

level of unions, or less formal

in the

worker and

worker coalitions with insider power, assets

to be put to alternative use outside the firm or even the industry to escape the

scope of the union.

exposed.

the union

own form of specificity on

best alternative use, possibly by other users.

the most exposed

his job.

level,

understood as the degree to which the asset would lose of

"specificity," here, is

it is

— the individual worker-firm

at

At the

It is

then the totality of firm- or industry-specific assets that

may be

and labor

interest

highest level of political interaction between capital

groups, even more generic assets become appropriable through such measures as the right

to strike,

employment protection

the possibility

—

legislation,

redistributive corporate taxation, or even

historically quite relevant in the developing

world

— of outright state

expropriation.

2

Unbalanced Restructuring,

1.3

Sclerosis,

and Wage "Rigidity"

Problems of appropriability can have highly disruptive consequences on the functioning

of labor

and capital markets during adjustment. They generally induce the sluggish job

creation and excessive destruction that characterize adjustment crises,

employment problem. The prospect

for firms of

effectively increases their investment costs,

newly expanding

having to yield part of the value they invest

and depresses investment and job creation

if it is

in the

Given the depressed rate of creation, the economic system ought

sectors.

to keep destruction in the contracting sectors at a low

the creation rate,

and the ensuing

enough

to avoid wasting resources. Instead, the

jobs extensively during adjustment. At a time

excessive job destruction

and more

difficult

when

level

commensurate with

economy tends

intense creation

to destroy

and hiring are needed,

employment opportunities are the system's

endogenous way of restraining the bargaining position of workers in their transactions with

firms to avoid

wage surges and guarantee the return on investment required by

markets. Workers

who

in the formal sector

loose their jobs because of the gap between creation

and destruction

employment

in the informal

must

sector, or find themselves

is

financial

either take

orrmuch

less attractive

openly unemployed when some form of unemployment insurance

available.

Paradoxically, despite excessive destruction at the outset of adjustment, appropriability

also induces "sclerosis" in the adjustment process.

Sclerosis characterizes a productive

structure that, ultimately, does not adjust sufficiently to

sectoral composition of output, adopting

new

conditions

new techniques, changing the

— by changing the

capital-output ratio,

In the presence of appropriability, the ultimate extent of restructuring

etc.

is

hampered by

the high effective creation costs brought about by transactional inefficiencies.

The observed wage behavior

differs

implied by the micro-structural inefficiencies

from the fixed wages assumed in traditional models of adjustment

(e.g.,

we

focus on

Lapan, 1976;

Neary, 1982; Edwards, 1988; Edwards and van Winjbergen, 1989). Those models assume

that wages are fixed in terms of the expanding sector's good, or a basket with a large share

of

it

— a necessary condition

adjustment, however,

is

for excessive destruction. Empirical evidence

on wages during

not supportive of that assumption. In her careful description of

See Thomas and Worrall (1994) for an analysis of appropriability through state expropriation in the

case of foreign direct investment.

Latin American labor-market legislation, Cox- Edwards (1993) finds that

minimum- wage

laws have become largely nonbinding in Latin America today.

In comparative studies,

authors such as Fallon and Riveros (1989) or Horton, Kanbur and

Mazumdar

great degree of

wage responsiveness during the adjustment experiences of a broad sample

of developing countries.

In our model, wages

although rigidity

appear

may move with

(1994) find a

will still

exactly the

same

in

may

look quite flexible during adjustment,

more subtle ways. In extreme

flexibility as in

an

efficient

cases,

we show

that wages

economy, but, in order to do

so,

they require the "quantity" movements of high destruction and underemployment usually

associated with rigid wages

— a phenomenon we

market problems may disrupt quantities but leave

show that wages are characterized by a mixture

of

which

is

little

trace

of "covert"

on

prices.

and "overt"

other words, labor

More

generally,

rigidity,

the degree

in labor

variability,

a better measure of the appropriability

markets can be found in the degree of labor market segmentation. Indeed,

when

the degree of asset specificity and appropriable quasi-rents differ across sectors

as

normally the case,

is

we

ultimately determined by the structure of creation costs.

Rather than looking at empirical wage

problem

call covert rigidity. In

for

example, between the formal and informal sectors

—

it

—

is

very natural that wages also differ in equilibrium. Appropriability can thus very naturally

account for labor market segmentation, which

in the developing world (e.g.,

1.4

By

is

a preponderant feature of labor markets

Lopez and Riveros, 1989; Fallon and Riveros, 1989).

Policy Responses

the nature of their driving assumption, fixed-wage models often disassociate the treat-

ment of the destruction margin

dynamics

— driven

by fixed wages and their ad hoc adjustment

— and that of the creation margin — driven by investment dynamics. This typ-

ically results in

destruction,

a dichotomy between a "short-run" analysis of the

and a more

ciation, fixed-wage

different policies

effect of fixed

wages on

neoclassical "long-run" analysis of creation. Because of this disso-

models do not naturally lead to an integrated view of the joint

on the creation and destruction margins. In

fact,

effect of

the popular prescription

of gradualism in the context of those models can be quite sensitive to the fact that its effect

on creation

is

typically not explicitly modeled. In contrast, one of the central features of

policy analysis in this paper

in

is

the emphasis on the fact that policies targeted at distortions

one margin typically have counter-productive implications

margin.

The

real test

is

for distortions in the other

whether gradualism can close the wedge between creation and

destruction to help redress the transitional employment problem.

From

that point of view,

we

an

find little reason in our analysis for

effective "synchronizing" effect of

Gradualism can only reduce the destructive

creation and destruction.

by also reducing the economy's already depressed creation

constitute,

by

itself,

an effective solution

in

rate,

terms of economic

gradualism on

effect of

adjustment

and thus does not seem

to

efficiency.

Policy analysis must go beyond the gradualism versus cold turkey debate, and examine

the managed-adjustment policies needed in face of unbalanced restructuring. Despite the

fact that the

economy's

ills

we

are ultimately institutional in nature,

focus, for a

ber of reasons, on macroeconomic rather than institutional cures. There often

government can do to directly remedy incomplete-contracting

When

social institutions

feasible, or undesirable

of

macroeconomic

and

legislation are concerned,

because of

policies

distortions in the creation

is

its social

On

in turn

the

inefficiencies in transactions.

may be

either politically in-

and distributional consequences. Our analysis

and destruction margins.

ation calls for a creation incentive

may

is little

conducted in terms of canonical policies that directly address

the creation and destruction margins

intensified hiring

change

num-

is

(e.g.,

It is

On

clearest.

there that the interaction between

one hand, the depressed rate of cre-

an investment tax credit or an export subsidy), but

put pressure on the labor market and exacerbate destruction.

the other hand, excessive destruction-calls for job-protection policies

subsidies in the contracting sectors or "gradualism"), but those

by raising the opportunity cost of labor.

What

needed

is

addresses distortions in both margins simultaneously.

in the presence of appropriability requires a

panding sectors and employment protection

debate on gradualism, the implication

is

We

is

may

(e.g.,

employment

discourage creation

an integrated program that

argue that healthy adjustment

combination of creation incentives in the exin the contracting ones.

that a gradualist approach

Going back to the

must be supported by

vigorous creation incentives to be effective.

The

rest of this

paper follows in four sections.

First,

we develop

in section 2 a simple

model of adjustment that captures supply-side aspects of adjustment and of the disruptive

role of appropriability. Section 3 turns to the analysis of the traditional gradualist prescription,

and section 4 derives the optimal

5 presents

2

To

policies that

can restore

efficiency. Finally, section

some concluding remarks.

Appropriability in a Simple

fix ideas,

we

Model

of Adjustment

take the example of trade reform as a paradigmatic case of adjustment.

start with a simple

model that presents our perspective on restructuring

in the

We

adjustment

process and of the disruptive effect of appropriability. In order to have a simple solution, we

assume that adjustment

is

linear in all its aspects. This results in

such as instantaneous reallocation in the

and

linearity,

which we relax

in sections

4.

A

2.1

features,

economy, and degenerate destruction more

However, our main results do not hinge on

generally.

3

efficient

some unpleasant

Simple Model of Adjustment

Our economy has two goods,

X

(

"exportables" ) and

M

(

"importables" )

.

Importables are

used as the numeraire. The representative infinitely-lived household has linear

utility:

f°[Cx {s) + Cm {a)]e<'-^ds.

(1)

Household labor supply

perfectly inelastic, with a labor force equal to L.

is

Both goods are produced with

units in such a

way

similar Leontieff technologies.

that, for each of the goods,

We

choose measurement

one unit of sector-specific capital and a

worker combine in fixed proportions to form a production unit and produce one unit of the

good.

Initial conditions.

tional trade

and

We assume that before liberalization the economy is closed to interna-

in long-run full-employment equilibrium. Since

with respect to

X

initial allocation

of factors

and

M,

is

both goods have pre-liberalization prices equal to

arbitrary.

We let L^

and L~ stand

Liberalization. Let the international relative price of

which

=

0.

is

given for the country.

It

is r,

We assume that

in the

M

An

unanticipated

X

with respect to

M be

6*

>

1,

trade liberalization takes place at

full

the capital account

is

open, and that the world interest rate

the same as the domestic discount rate. Since consumers are indifferent between the

two goods, they specialize

in

good

M.

Producers, on the other hand, would like to specialize

good X. The cost of setting up a new production unit

is Cq,

cost that stands for physical capital as well as organizational

H

employment

amounts to exposing domestic consumers and producers to the international

relative price.

in

for

and the

1

X sectors, where a minus-sign superscript denotes pre-liberalization quantities.

and

t

consumers are indifferent

(t)

takes place in the

X sector, with

all

which

is

a generic investment

and training

costs.

Creation

workers being hired from the unemployment pool

17(f).

Appropriability.

The

appropriability of investment

is

an incomplete-contracts problem

that can

afflict

and the worker

there

may

the efficiency of the job-creating transaction between a firm that invests cq

it

When

hires.

not be a

way

part of the investment

to write a binding

is

"specific" to the

production unit,

and complete contract to ensure that

all

the

quasi-rents attributable to the investment go to the firm.

To capture

this idea,

we introduce a parameter

investment whose quasi-rents are appropriable. To

<t>

6

that measures the share of

(0, 1]

fix ideas,

consider a job that requires a

$1,000 investment, of which $700 must be spent on equipment that can be resold at cost and

$300 on specific training to the worker that

is

operates only at the individual firm-worker

binding contract can be signed.

If

When

of no use elsewhere.

level,

the parameter

<f>

effectively raise

equal to 0.3

the worker belongs to a powerful union, or

protected by legal restrictions, dismissing him and selling the machine

and would

is

appropriability

if

if

his job

may be more

no

is

difficult

<j>.

Incomplete contracting creates a flow of appropriable quasi-rents that must be shared

by the two parties through a bargaining process. Let

a firm and a worker

who meet

at time

to the continuous-time generalized

the worker

The

and

(1

— (5)

surplus IT(£)

and the firm can

is

solution.

A share

/3

(0, 1)

of the surplus goes to

equal to the value that the match creates above

effectively claim as their best alternative.

(1

— <P)cq

if it

drops out of the match.

worker's best alternative in the calculation of the match surplus

unemployed and searching

for

another job.

[9*

We

what the worker

Because of the appropriability

of its investment

w(t), equal to the opportunity cost to a worker of remaining

It is

G

goes to the firm.-

problem, the firm can only recover

The

denote the surplus over which

must bargain. Bargaining takes place according

t

Nash

IT(t)

is

the shadow wage

on the job rather than turning

can thus write the match surplus

- w(s)] e'^^ds -

(1

-

(j>)co,

t

>

as:

0.

equal to the present value of the future revenue 6* from production minus the worker's

shadow wage

tu,

after subtracting the protected part of the creation cost cq.

the opportunity cost w(s) for the worker of holding the job

probability H(t)/U(t) of finding another

is

match times the part

In turn,

equal to the instantaneous

@Tl(t) of the

match surplus

he would get there:

(3)

Equilibrium Conditions.

We

w(t)

= ^f3U(t).

assume

free entry for

8

new production

units.

This means

,

that, as long as entry

entrant's share of the

taking place, the cost of creating a production unit

is

is

equal to the

match surplus plus the part of investment that can be protected. 3

Rearranging this condition, we get

4>co

(4)

The

it is

match surplus

cf>

=

0,

is

called

(l-P)U(t).

match surplus must compensate

firm's share of the

investments

=

on to make. This shows

created

if

and only

if

there

is

the free-entry condition becomes H(t)

=

exactly for the unprotected

it

clearly that,

under

free entry,

a positive

an appropriability problem. Otherwise,

0,

which by

(2) is

if

the standard condition

that equates Cq to the present value of quasi-rents.

Solving out for

II(£),

equations (3)- (4) imply the following equilibrium conditions for

all

t>0:

[0*

(6)

- w(s)] e^^ds,

L m (t) = L"

if

w(t)

<

0<L m (t)<L-,

if

w(t)

= l;

Lm (t) =

if

w{t)

>

U(t)

(7)

1,

= L- Lx (t) - L m (t),

H

(8)

0,

1;

(t)

= dL x {t)/dt,

where

5(()

(9)

(l

+ i)o,

W §§^,

.-^

=

(10)

and

(ii)

The

=

first

equation governs free entry in the economy, where the "effective" creation cost

c(t) is distorted

by a factor

6.

4

This distortion

is

due to the problem of appropriability. In

equilibrium, the part of investment whose quasi-rents are appropriated by workers

The "appropriation" parameter

b given

by

(11)

is

is bco-

increasing in the degree of appropriability

3

FonnaUy, the free-entry condition is cq = (1 — /3)II(t) + (1 — <f>)coFor creation to be economically sensible, we must assume that the effective creation cost

so as to be covered at least by the present value of revenues

i.e. (1 + 6)co < 0' /r.

—

is

low enough

<p

and

bargaining power of workers

in the

It states

/?.

The second equation

M sector

that production units in the

is

the exit condition.

are scrapped or preserved depending

on

whether their associated quasi-rents are negative or positive, which in turn depends on

whether the shadow wage w(t)

The

latter

is

is

greater or smaller than 1 (productivity in that sector).

given by equation (10), which follows from (3) and

(4).

The

third

and fourth

equations are accounting equations that define unemployment and hiring.

An attractive feature of the decentralized-bargaining equilibrium in

it

this

economy

is

that

converges to the efficient competitive outcome as the appropriation parameter b goes to

In the limit, the effective creation cost in (9) becomes undistorted,

zero.

wage

down

in (10)

becomes whatever

is

and the shadow

needed to clear the labor market and bring unemployment

5

to zero.

The Nature of Unemployment. The free-entry condition

respect to

t

and solved

for the constant

on investment. Expression

can be differentiated with

(5)

shadow wage that guarantees the required return

(10) can then be used to calculate, for a given level of hiring,

the level of unemployment needed to yield the required shadow wage in equilibrium.

We

get

(12)

w(t)=e*-r(l + b)co;

13 >

«W = *--K?+i) co g ">-

<

It is clear that, in

new

locations,

an economy with important needs to restructure and hire workers in

unemployment

appropriability. If

is

the result of the positive match surpluses that result from

unemployment were

zero, workers

would find

it

infinitely

the positive surplus of an alternative job. This outside alternative would

wage

infinite (equation 10),

easy to capture

make

their

shadow

which renders job creation prohibitively expensive and generates

unemployment. Unemployment

is,

thus,

an equilibrium response of the economic system

that restrains the bargaining position of workers in the presence of appropriability and

preserves the profitability of investment.

and intense gross hiring require high

wages and keep them at a

As equation

transitional

level that

(13)

makes

clear,

times of adjustment

unemployment to prevent surges

makes job creation pay

in

shadow

off.

Equation (10) turns into the full-employment equation once we multiply both sides by U(t) and set

b

= 0.

10

and Unbalanced Restructuring

Sclerosis

2.2

Sclerosis.

We can now solve

wage together with the

in

which sector

The

M

inaction range

enough

1 for

for the

economy. Solution (12)

for the evolution of this

exit condition (6) defines

an inaction range

in

for the

shadow

parameter space,

remains profitable and no adjustment takes place following reform.

is

<

given by 0*

+ r(l + b)co,

1

which clearly indicates that

it is

not

world relative price 6* of exportables versus importables to be greater than

restructuring to occur. 6* must be sufficiently larger than

1 to justify

spending the

additional creation costs.

Note that there

the inefficient

is

a segment 6* G

economy does not

(1

+ rco, 1 + r(l + b)co]

adjust, while efficiency

greater the appropriation parameter

b,

the larger

is

this

of the inaction range where

would require adjustment. The

segment of the inaction range.

Thus, appropriability can prevent adjustment from taking place altogether in cases when

efficient to adjust.

it is

we term

This

is

the

first

manifestation of an effect of appropriability that

sclerosis.

Sclerosis arises in the

ficiently in

response to

economy whenever the productive structure does not adjust

new

conditions

— by changing the sectoral composition of output,

adopting new techniques, changing the capital-labor

ratio, etc.

In this particular case, ap-

propriability can cause the productive structure to be locked into its past

response to the opening of trade, despite the efficiency of doing so.

is

suf-

and not adjust

The reason

in

for sclerosis

the high effective creation costs induced by appropriability (equation 9), which reduce

the incentive for creation as well as the hiring pressure on wages and destruction (equation

12).

The

fact that sclerosis takes the

the degenerate

incomplete

extreme form of

initial distribution in

— rather than

fully

M

the

aborted

sector.

fully

2.4, or

is

due to

Generally speaking, sclerosis leads to

— restructuring, as

technology model analyzed in sub-section

aborting restructuring

the case in the heterogeneous-

is

when the M-sector

exhibits diminishing

returns to labor.

Unbalanced Restructuring. Outside the inaction range, the

and dynamics are governed by equations

(14)

dU(t)/dt

(7)

and

= -H(t)

(8)

with

11

with

M sector

Lm (t) =

J7(0)

= L".

0:

is

instantly scrapped

Taking (13) into account, the solution to

U(t)

(15)

this

equation

= L^e

*»

is,

for

t

>

0:

«,

Lx (t) = L-U(t),

Lm {t) =

The whole

M sector

0.

scrapped instantly following reform, leading to a jump in unemploy-

is

ment. However, creation in the

X sector

is

progressively over time. Asymptotically, the

gradual and can only absorb the unemployed

economy

adjusts fully

and reaches

employ-

full

ment.

This path has very

outcome corresponds

the efficient

economy

inefficient characteristics.

to the limit

is

when

6

As we have

goes to zero.

seen, the efficient competitive

easy to see that adjustment in

It is

instantaneous and complete at time

t

=

This means that creation

subject to appropriability problems exhibits sluggish creation.

and destruction are out of balance and lead to

instantaneous efficient adjustment

show

in the

is

transitional

unemployment

on creation and destruction does not hinge on

this.

its efficient level is

Although

we

effect of appropriability

Moreover, we show that, at the outset

of reform, appropriability generally leads to insufficient creation

efficient

costs.

not a very attractive feature of this simple model,

convex model of section 3 that the de-synchronizing

compared the

economy

In contrast, an

0.

and excessive destruction

outcome. The fact that, in the present case, destruction

is

equal to

only due to the maximal, instantaneous rate at which the latter takes

place.

2.3

Covert

Wage

Rigidity

Although this model exhibits the transitional unemployment usually associated with

wage models

may appear

(e.g.,

Lapan, 1976; Neary, 1982; Edwards and van Winjbergen, 1989), wages

quite flexible. In fact, in the special linear case

the same as what they would be in an efficient economy.

actual

fixed-

wage paid by exporting

we

To

are analyzing, wages are

see this, denote

firms (the only firms after liberalization).

not equal to the opportunity cost of labor, w, for

we need

to

add the part of the match

surplus that goes to the worker, which in flow terms amounts to rbcQi

wx = w + rbco = 6* — rcQ.

12

Note

wx the

that wx is

by

This expression

efficient

is

independent of

economy where

b

=

adjustments

ployment

—

in the

and

therefore exactly equal to the

is

it

from surging beyond that

a hidden form of rigidity that manifests

As we

In Caballero and

will see in the

Hammour

itself entirely in

(1994),

rigidity,

is

inefficient are the

wages

level

quan-

during times of intensified

we dubbed

3,

the equilibrium quantities that

this

phenomenon

observed wages exhibit, more generally, a

restrain

them from being even

consistent with the empirical evidence

is

covert rigidity.

which partly keeps them above their

and partly requires quantity adjustments to

variability of

an

wage appears adequate, but actually harbors

convex model of section

mixture of "overt" and "covert"

The

in

form of unbalanced restructuring and high transitional unem-

— needed to restrain

it.

what

as in the efficient outcome,

hiring (see equation 10). In other words, the

support

wage paid

0.

Although the wage behaves

tity

ft,

efficient level

higher. 6

on wages, which

generally exhibit a great degree of responsiveness in case studies of adjustment (Fallon and

Riveros, 1989; Horton, Kanbur, and

Mazumdar,

1994).

However,

caveat for the interpretations of those findings, from which

it

raises

an important

some authors have concluded

that adjustment crises are not due to malfunctioning labor markets. In their recent

Bank study

World

of the role of labor markets in the process of adjustment, for example, Horton,

Kanbur and Mazumdar (1994) conclude:

[Tjhere are three possible explanations as to

during stabilization. The

cause of real wage

not working well be-

The evidence presented by the

case studies certainly

that the labor market

does not favor the view that real wages were

employment. Even

for Chile,

the longest, real wages

nations: aggregate

fell

persist

is

first is

rigidity.

why unemployment may

and therefore led to un-

where unemployment was highest and persisted

dramatically.

[...]

demand feedback from

output market imperfections.

rigid,

[T]his leaves the other

two expla-

declining real wages to output

and

(Vol. 1, pp. 19-20)

In the linear model, the shadow wage rises in terras of importables following reform. This is very

and is precisely the reason why the

sector contracts. In our convex model, this shadow wage

remains unchanged while the

sector is being depleted, and jumps to its long-run value when the process

is completed.

For the

sector, the product-wage in both models also generally rises in the long run. This effect is

only due to the fact that creation costs were assumed fixed in terms of importables, thus making it cheaper

natural,

M

M

X

Had we fixed those costs in terms of exportables instead, the long-run product

sector would have been unchanged. In the transition, however, the product-wage in the

immediately to its long-run value in the linear model, but remains temporarily lower in the

to create following reform.

wage

in the

X

jumps

convex model to induce

sector

X

intense creation.

13

Our model

clearly

shows that looking at the path of

the extent of labor market rigidity

exogenously fixed

wages

real

in isolation to assess

— which comes from the practice of modeling wages as

— can be quite misleading.

Variable real wages do not necessarily imply

that the labor market functions adequately. Other forms of empirical evidence

is

needed

to assess the workings of the labor market. Looking at the degree of segmentation in labor

markets

— which

1989; Fallon

problems.

preponderant

and Riveros, 1989)

segmentation

2.5,

is

is

Another

in the developing

world

— may constitute a better

(see, e.g.,

Lopez and Riveros,

As we explain

test.

a very natural feature of a labor market

afflicted

in sub-section

by appropriability

can be gleaned from the institutional features of

class of evidence

labor markets that characterize the more "visible" aspects of appropriability. Cox- Edwards

(1993) gives a careful account of the predominant institutional distortions in Latin

American

labor markets. These include employment protection laws, payroll taxes, and antagonistic

labor-management relations that encourage confrontation and costly settlement procedures.

Consistently with the authors cited above, she concludes that

the

list

of the

most pressing labor market

issues in Latin

minimum wages

are not on

America today.

Productivity Cleansing During Adjustment

2.4

Our

structural approach, based on the

the adjustment process further, once

it is

embodiment of technology, allows us to characterize

we

allow for heterogeneous technologies. In that case,

simple to see that the shock of liberalization affects the least

the most. Thus,

if

gives rise to a

phenomenon of productive

which finds growing support in the empirical

To develop

this point,

we modify

tion of production units in the

efficient

productive units

"cleansing" in the economy,

literature.

the above model and assume that the initial distribu-

X and M sectors

is

heterogeneous in the technologies in use.

For each production unit, we use a as an index for the outdatedness of the technique in use

and assume a productivity oil— a. Technology

to a

available today in

both sectors corresponds

= 0.

The distribution of production units

across techniques

is

given by the history of technol-

ogy adoption (see Caballero and Hammour, 1994) and government intervention. For each

sector,

we assume a non-degenerate

the scrapping margin

a~

is

initial distribution

over the range a

determined by the zero profit condition

1

— a~ =

14

it;

,

€

[0,a~],

where

and the shadow wage

w~ =

is

1

— r(l + b)cQ

determined in the same way as in equation

(12).

7

Consider what happens after liberalization. The interesting phenomena here arise inside

the old inaction range (6*

there

is still

<

1

+r(l +

M

a complete and instantaneous scrapping of the

followed by instant scrapping of

condition, which

price.

where we assume the economy

b)co),

is

now

all

otherwise

Liberalization

production units that do not satisfy the

different for the

The new scrapping margins

sector.

is,

new

is

zero-profit

two sectors because of the change in their relative

M and X, respectively, are given by

for sectors

l-a m = w

(16)

and

6*(l-ax )

(17)

where

w

is still

= w,

given by the free-entry condition in the

after the initial scrapping are as before.

X sector (equation

The unemployed who

lost their

shock of liberalization are hired gradually into the expanding

12).

Dynamics

job after the

X sector,

initial

while production

units in both sectors that were not scrapped initially subsist in the long run.

Following liberalization, the scrapping margins (16)-(17) tighten in both sectors by the

amount of increase

in the product wage. This

phenomenon of

"cleansing" of the productive

structure following reform, that results in an improvement in average productivity, finds empirical

support in the recent literature

plants during the 1979-86 period). It

margin tightens more markedly

(see, e.g., Liu's

is

for the

also

1993 study of Chilean manufacturing

immediate from (16)-(17) that the scrapping

M sector than

implies that productivity cleansing following reform

is

for the

X sector (a„,

likely to

< ax ). 8

This

be more extensive in im-

portables than in exportables, which also finds empirical support (see,

e.g.,

Tybout, De

Melo and Corbo, 1991; Haddad, 1993; Corbo and Sanchez, 1992; Marshall, 1992).

With heterogeneous

The shadow wage

technologies, the problem of sclerosis discussed in sub-section 2.2

determined by the free-entry condition, even though we assume that the economy

a worker is still

to find a potential entrant, even if such a threat is not realized in equilibrium.

In fact, the only reason the scrapping margin tightens and the product wage rises in the

sector is

because we have assumed that creation costs are fixed in terms of importables. Had we assumed them fixed

in terms of exportables, the product wage in the

sector would have remained unchanged. Had we also

assumed convex adjustment costs, the X-sector wage would have fallen in the transition.

at time zero

is

is

in long-run equilibrium with zero entry. This is because the threat point of

X

X

15

,

gains a technological dimension.

One can

and

see from equations (12)

(16) that a greater

degree of appropriation b lowers the shadow wage and loosens the scrapping margin a m in

M

the

sector. All production units with a

€

—

[tcq

(6*

—

l),r(l

+

b)co

—

(0*

—

despite the fact that they ought to be scrapped in an efficient world. Sclerosis

just a

problem of producing the wrong goods, but

also of

producing

all

subsist

1)]

is

goods with

now not

inefficient

technology.

Unemployment, the Informal Sector and Segmented Labor Markets

2.5

In developing countries, where

unemployment

benefits are sparse at best,

unemployment

is

typically "hidden" in the form of participation in low-productivity informal-sector activities.

Instead of a surge in open unemployment, the transitional employment problem

may

take

the form of a surge in informal sector employment.

The segmentation

of labor markets between the formal

naturally in our context,

if

and informal sector

arises very

informal-sector technology requires less asset specificity or allows

workers to avoid entering into a bilateral transaction with capital owners. 9 The simplest

case in which this happens

and assume

is

when the technology requires no

that, in the informal sector, "workers can

that requires no capital and yields a

The only

all

We modify our model

become self-employed

— possibly quite low — productivity

as close as possible to the above model,

and assume that

capital.

we denote

total informal sector

7r

in

<

an activity

1.

To

stay

employment by U,

workers hired in the formal sector come from the informal one.

modification to equilibrium conditions (5)-(ll) comes from the fact that

must add the productivity of informal-sector

we

activity to the opportunity cost of labor in

(10):

w_,^ =

,

Hit)

W)

bC0+lr

-

This means that the level of informal sector employment U(t) needed for a given

hiring

is

now

level of

higher than in equation (13), and equal to

PW" y-.)5(i+»)» *ft>The

possibility of engaging in informal-sector activity strengthens workers' threat point,

which must therefore be

offset

by an even higher

level of

U

to maintain firm profitability.

For an analysis of some of the consequences of labor market segmentation in small open economies, see,

e.g.,

Agenor and Aizenman (1994).

16

The dynamic equation

(15) characterizing U(t)

becomes

U(t)=L^e-

A

more productive informal

The

-o

down

sector further slows

divide between the formal and informal sector

is

10

the adjustment process.

only one aspect of the segmentation

that can arise in the presence of appropriable investment. Naturally, as

any sectoral differences in the degree of asset

specificity

can cause segmentation. Moreover,

many differences in the determinants of profitability that

can interact with appropriability and lead to wage

of the

we mentioned above,

arise after some

differentials

model with heterogeneous technologies developed

— as

is

investment

is

sunk

the case, for example,

in the previous sub-section.

11

Gradualism

3

Our approach

to adjustment crises provides us with a framework for the study of alternative

policy responses. In this section

and

in the next

we turn

we concentrate on the popular

prespcription of gradualism,

to the question of optimal policy design.

Our

analysis of gradualism

provides an opportunity to generalize to a convex model of adjustment the central results

we obtained

We

section.

have seen that appropriability induces two distortions in the transition: depressed

creation

crisis.

model of the previous

for the linear

and excessive destruction. The wedge between the two

Much

transitional

gives rise to an

of the popularity of gradualism derives from the idea that

employment

crisis

assumption that creation

slowing

down

is little

affected. In fact, there is little reason

both creation and destruction

adjustment in the process

can

relieve the

by slowing down destruction, presumably under the implicit

the transition will not also exacerbate the sluggishness of creation.

effect of

it

employment

— are ambiguous, and

why

slowing

The

net efficiency

down

— and of delaying the net benefits of

likely to

depend on the

specifics of the

situation. 12

Note that exactly the same

would

from the introduction of unemployment benefits.

we need to make additional assumptions about the out-ofequilibrium uses of the non-appropriable component of capital, including the relation between those uses

and current productivity and location. Most reasonable scenarios, however, lead to wage differentials that

To

calculate the actual

effect

wage

arise

differentials,

are related to the relative profitability of the production units being compared.

There

a class of models characterized by over-investment, where the pace of both creation and destrucand where the welfare-improving properties of gradualism are therefore unambiguous.

A good example can be found in Gavin (1993), who advocates gradualism based on a congestion model of

search. His assumption, that the matching function is a concave function of unemployment only, implies

is

tion are excessive,

17

l

To uncover

the tension between the effects of gradualism on the creation and destruction

The

margins, we analyze two extreme cases.

first

extreme highlights the distortion

creation margin and corresponds to the simple linear model presented above.

destruction in that model

is

down

creation further,

other extreme

is

is

we analyze

Since gradualism can only

sluggish creation.

its efficiency effect is

what would be required instead

The

unambiguously negative. In that case,

"accelerationism."

highlights the distortion

on the destruction margin.

same simple model analyzed above, but now with a

consist of the

Convex creation

creation costs.

the special assumptions

special

that the dominant distortion

destruction side. In that case, gradualism

is

and destruction.

Its

main

effect will

always on the

when the

multaneously slow down destruction and accelerate creation. Because

is

and

always beneficial.

reveal the limitations of gradualism

margins simultaneously, gradualism

is

It

form of convex

costs lead to non-degenerate destruction dynamics,

we make imply

Those two extreme cases

Because

instantaneous in both the efficient and inefficient case, the

only problem with transitional dynamics

slow

in the

it

goal

slows

is

to

si-

down both

unlikely to be an effective "synchronizer" of creation

be to spread out transitional underemployment costs

them

a more general setting, the economy

over time, but

is

will present a

mixture of the two extremes we analyze, with phases of adjustment where

gradualism

beneficial,

is

gradualism and

distortions

is

unlikely to reduce

its

effectively. In

and phases where accelerationism

is.

This alternation between

opposite, depending on which of the creation- or destruction-margin

dominant, shows more generally the limitation of using a single policy

in-

strument to address distortions on the two margins. Policy analysis should go beyond the

gradualism versus cold-turkey dichotomy, to the design of managed adjustment programs

with multiple policy instruments. This we proceed to examine in the next section.

Throughout

this section,

we model a

gradualist reform as the temporary introduction

of a path of tariffs {r(t)}t>o following reform to protect the importables sector.

the

tariff is

We assume

small enough so the domestic relative price of exportables 6{t) remains above

one:

* (t »

" (TTRJj)

a

t£0

'

In order to reduce technical complications in the analysis,

capital account

is

closed

and that the

interest rate r

is

-

we assume from here on

given by the subjective discount rate

that high unemployment, by facilitating matching, pushes creation above

18

that the

its socially efficient level.

in the utility function (l).

constraint

is

not binding

We

13

(i.e.,

assume parameters are such that the balance-of-payments

desired domestic investment does not exceed desired domestic

saving).

Gradualism with Sluggish Creation

3.1

In this sub-section,

to gradual opening-up in one extreme case that corresponds to

we turn

the simple linear model of sub-section

same when a

the

tariff is

2.1. It is

introduced at time

t

easy to see

=

equations (5)-(14) remain

except that the world relative price 6*

0,

must now be replaced by the distorted domestic price

is

how

the shadow wage

6{i). In particular,

now given by

w(t)

(18)

= e(t)-r(l + b)co.

Assuming model parameters are such that even with gradualism the economy does not

inside the inaction range

fall

unemployment

is

now

>

that 6(t)

C/(t)

= L"e

define two paths of reform.

Jo

The

oco

given by 6

path

is

=

(t)

+ r(l + b)co,

for all

9* for all

t

>

0.

d

\

>

t

It is clear

The

the path of

is

characterized by an

c

cold-turkey path {d (t)}t^o

simply

more sluggish creation

and a smaller

X sector.

destruction

the same in both scenarios. Gradualism in this case has one

Since

1S

from equations (18)-(19) that the gradualist

characterized by lower shadow wages, higher unemployment,

is

0),

£>o.

gradualist path {0 g (t)}%LQ

increasing 6 9 (t) that reaches 6* asymptotically.

c

1

given by

(19)

We

(i.e.

we have assumed

that

we remain

outside the inaction range,

reduce the relative-price incentives to create in the exportables sector.

It

effect,

which

is

to

leads to reduced

creation and, given complete destruction in importables, higher unemployment.

We analyze

define

it

welfare in this

economy from the point of view of allocational

efficiency,

and

as the present value of aggregate domestic income net of investment expenses:

(20)

W(t)

=

J™

[6*Lx (s)

+ Lm (s) - coH(s)) e^^ds.

The difficulty comes from the change in the relative price of importables delivered domestically and

importables delivered overseas that results from a gradual change in the tariff rate. This means that a world

interest rate that is constant in terms of the

good delivered overseas, will not be so in terms of that good

M

delivered domestically.

To avoid changes

in the interest rate,

interest rate to the subjective discount rate.

19

we

close the capital account

and equate the

Although,

in principle,

separable,

we do not

with linear

utility the allocational

much comfort from

derive

ments' ability to redistribute income

in

ever, that, once reform has been decided,

grounds

and

given the severe limitation of govern-

this,

a non-distortionary way.

It

does seem to us, how-

an adjustment path that ranks high on allocational

have to avoid wasted resources

will

and distributional problems are

form of open or hidden unemployment,

in the

rank high on distributional and poverty-alleviation grounds

will therefore potentially

as well.

The appendix calculates

ualist

adjustment

(W9 ),

welfare for three scenarios: cold- turkey adjustment

productive structure intact). First

appropriability problems,

private incentives,

it

which

is

we show

which corresponds to keeping the old

,

that, notwithstanding the disruptions

cold-turkey adjustment

if

will also

W

(Wn

and no adjustment

c

is

due to

desirable from the point of view of

be desirable from a social point of view:

- W"(0) = -

(0)

{Wc ), grad-

[(*•

-

1)

r

clearly positive outside the inaction range.

- r(l + b)co] L-,

14

Turning to gradual adjustment, we show that

W

9

-

(0)

W

c

(0)

=-

f°° W*

-

9 (s))

U9 {s)e- r ^-

t)

ds,

Jo

where

U9 (t)

expression

designates unemployment along the gradualist path.

is

negative

when 6 9 {i)

stays below 6*,

It is clear

and that gradualism

is

that this

inferior to cold-

turkey adjustment. In this extreme linear case, gradualist adjustment can only affect the

creation margin. It slows

unemployment

3.2

down an

already depressed creation rate, and results in increased

as well as a delay in the net benefits of adjustment.

Gradualism with Excessive Destruction

The reason why gradualism

destruction

precisely

is

fails

to have any beneficial effect in the linear

degenerate and happens instantaneously.

on the idea

that,

The

model

is

that

gradualist argument hinges

by slowing down the destruction of the old structure, a gradu-

14

The reason for this is that, outside the inaction range, the private distortion 6co to creation costs

exceeds the social cost of the additional unemployment that results from creating an additional unit (equal

to U/H = bco/w by equation 13, which is less than bco outside the inaction range), while the private value

of a new unit created in the

sector is less than its social value (because the private shadow wage exceeds

the social shadow wage of zero in the presence of unemployment). Thus, a private decision to create is both

X

cheaper and yields greater value from a social perspective.

20

alist

approach can give more time

for creation to build

up the new one, and thus reduce

transitional under-employment.

To capture

this effect,

instead that fast creation

is

we drop the assumption

The shadow wage no

costly.

following reform, precipitating

all

of linear creation costs

longer

jumps

to

its

and assume

long-run value

destruction at that point, but converges over time to

long-term value and brings about a progressive destruction of the

M

its

sector.

In order to highlight the beneficial effects of gradualism on destruction in as simple a

setting as possible,

we make

special assumptions

— on the form of creation costs and on

— that greatly simplify the analysis and imply

the initial distribution of production units

that the destruction-margin distortion always dominates. In this extreme case, gradualism

is

always a beneficial

sub-section,

we

—

albeit far

from optimal

— policy

response.

At the end of

this

more general assumptions.

discuss the implications of

The model. There are many reasons why an economy cannot instantly create a new

productive structure: time to build, slow learning and technology adoption, limited savings,

uncertainty, etc.

To capture some

of those effects,

and assume that the unit creation cost

is

we modify the model

increasing with the rate of creation H{t). This

can be due to standard convex capital installation and learning

to a non-degenerate distribution of potential entrants (see

the reasons explained above,

form ciH(t),

c\

>

we choose

in sub-section 2.1

for the

costs.

Diamond

It

can also be due

1994, chapter

1).

For

marginal creation cost the special functional

0.

Equilibrium conditions (5)-(ll) must be modified. 15 The change in the specification of

creation costs

means that the shadow

price signals (9)-(10) are

c(i)

(21)

now

given by

= (l + b) Cl H(t)

and

w(t)

(22)

Let us

first

=

§^bCl H(t).

characterize adjustment in this

economy without government

intervention.

We show by construction that, as long as 6* is not too large, the transition ends in finite time

T — creation, destruction and unemployment being positive before T, and zero afterwards.

Ongoing destruction requires that wages

M. By

exit condition (6), the

shadow wage

Naturally, as in sub-section 3.1, 6'

rise to exactly eliminate all quasi-rents in sector

will

have to be

1 for t

must be replaced by the distorted

21

<

T, and 6* afterwards

price 6(t) in those equations.

to prevent further creation:

16

{

'

We

[

use

(5), (21)

and

0<t<T;

~_

6*,

t>T.

(23) to solve for the creation rate

l-e- r T -*)], 0<i<T;

e'-i

(

r(l+6)ci

H(t)

(24)

1,

(

=

w(t)

(23)

X

t>T.

11

0,

This can be used to integrate the dynamic equation

using the boundary condition

(8)

Lx (0) = L-:

L x (t) =

(25)

L *" +

\

^fe

t

-e_I

^

(e

rt_

0<t<T;

l)

t>T.

The unemployment

rate along this path can be obtained from (23)

and

(22), taking (24)

into account:

,

s

U(t)

26

=

f

w

bclH(t) 2

< t < T;

~_

,

{

t

| 0,

>

T,

with the destruction margin adjusting to generate the required unemployment.

check that, provided that the technical condition (6*

employment L m

= L — Lx — U

initially

jumps down by

—

1)

£7(0)

<

^(1

+

and then

One can

£) holds, M-sector

falls

monotonically

to reach zero at time T. 17

Finally, the length

ment that the

T of the transition

is

transition be complete at T,

determined from equation (25) by the requirei.e.

LX {T) =

L. It

is

implicitly

determined by

the following equation:

r-i^-3E}±a&(E-«.

(27)

16

Note that, unlike the

1 to 1/6').

The same

linear model, the

shadow wage

holds for the actual product wage

initially falls in

wx /6'

in the

terms of exportables

(it

drops from

X sector, which must fall below 1

to

encourage intense job creation. In fact one can show that, for t < T, w z /0* = 1 — A b)e { Thus, although

the product wage falls in the transition, it falls by less

and exhibits more "overt rigidity

the greater

the appropriability parameter 6 is.

—

,

.

—

We need to check that dL m /dt < for t < T. Using (8), (24) and (26) to differentiate Lm =X-L I -U,

wegetdLm /dt = -H [l - ^(0* - l)e- r(5: -'>l Our condition is satisfied if and only if (0* - 1) < j(l+£).

17

.

22

This model with progressive destruction adds realism and insight, and allows us to

generalize to a convex setting our previous conclusions concerning unbalanced restructuring

and

sclerosis in the presence of appropriability.

and the disruptive

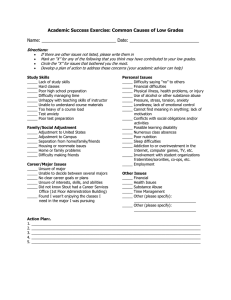

lines

effect of appropriability

The path

problems are illustrated

—

the solid lines correspond to an efficient economy (the limit as b

characterize adjustment in an efficient

Because

More

fast creation is costly, creation

and destruction

results:

(i)

T>T

6

Turning to an

.

inefficient

dT/db >

creation in the

in equation (27); (ii)

in that

reform.

To

economy with

>

b

while

1),

in equations (23)-(27).

economy are

0,

progressive.

unemployment

in the

we obtain the following

X sector

is

measured by T, which can be seen by

L x (t) <

L%(t) for

€

all t

(0,T^],

differen-

which means that

slower that efficient, because of the high effective creation costs

induced by appropriability; 19 (Hi) Sector

=

=

=

(b

18

(where the superscript "e" refers to the efficient-economy benchmark),

transition takes longer than efficient, as

tiating

at t

set 6

0).

importantly, they go hand in hand and therefore generate no

process (equation 26)

i.e.

economy we

The dashed

in figure 1.

correspond to an economy that suffers from appropriability problems

To

economy

of adjustment in this

M

suffers excessive destruction at the outset of

see this, note that, unlike the efficient economy, equations (24)

show that a segment of the

M sector

is

and

(26) taken

destroyed instantly after reform to generate

the unemployment required to prevent wage surges in response to increased hiring. This

is

more progressive destruction that depletes that

followed by a

sector over time; (iv)

wedge created between slow creation and excessive destruction gives

in

unemployment during the

a wasteful surge

transition (equation 26).

new

This model with non-degenerate destruction dynamics adds a

Gradualism.

mension to the welfare-analysis of gradualism.

exhibits sluggish creation

creation even further,

18

rise to

To generate the

figure

and excessive

We

have seen that the

we used the

inefficient

following parameter values:

r

=

di-

economy

destruction. Although gradualism will slow

may help by reducing destruction. Could

it

The

down

the latter effect overcome

0.06, 0*

=

1.2, ci

=

1.5,

and

L~ = L~ = 0.5.

19

To prove

this

we

must have H(0)

<

show that H(Q) < Hc (0). Differentiate free-entry condition (5) with respect to

and T >

into account: dH/dt = - \{'^ + rH, t

\ By contradiction we

first

time, taking (21), (23)

T

H e (0),

smaller (negative) slope

otherwise

<T

we would have H(t) > H'(t)

over the interval [0,7*] because of the

dH/dt than

in the efficient case. But H(t) cannot exceed H'(t) over the whole

e

would contradict the fact that

Since H(t) is decreasing, the fact that H(0) < H°(0) together with H(T) > H°(T°) =

implies that

=

the inefficient path {H(t)} crosses the efficient path {H'(t)} from below at a point t* € (0,T ). This

proves that L x (t) < L%(t) for all t* € (0,5*], for if L x were to exceed L% at some point, that point would

have_to be after t* and would mean that L x (t) > L%(t) from then on. But that contradicts the fact that

Lx(T') < L%(T°) = L.

T>T

interval [O.T*], because that

23

.

:

-i

o

n

in

t in

m

m

tii

ii

x)

i

i

/

/

CM

E

'-P

I

I

I

I

09"0

02'0

OE'G

Ofr'O

OO'O

Ol/O

S'O

fr'O

2"0

-

I'O

q.uawAo|diuaun

ui q.uatiiAo|diU8

[Al

E'O

IT)

a

r-

II

II

_

-i

IT)

-

XJ XJ

.

i:

l

\

\

-

ro

\

\

V

\

^

x.

X.

^

CM

x

N

^^^ v

m

E

4J

>^

X.

"V

^

^w^"S^%

^^^.

-v

^^^^^^

1

001

1

—

.1

1

OB'O

X

1

08'0

1

1

OZ/0

1

1

09'0

uj q.uaiuAo|duja

1

OS'O

E£'Q

frS'O

91'0

uoiq.eajo

80"0

00"0

making gradualism a

the former,

To address

this question,

r

l|r(

The

)

—

I

we

a* j —

write aggregate welfare in this

roo

= tstll±s. +

economy

r

Jo

as

i

[(*'

-

term corresponds to welfare

first

remedy?

useful

l)(Lx (t)

if

- L-) -

U(t)

- - Cl H(ty e~ rt dt.

no adjustment takes place. The second term

is

equal to the improvement in welfare due to adjustment: the increase in the output of units

that are reallocated from the

transitional

The

unemployment, minus

loss of

That

creation.

M to the X

minus the

loss of

M-sector output due to

total creation costs.

output due to unemployment can be considered an "unemployment-cost" of

is

because, by (26), lost output per unit-flow of creation

(28)

H(i)=

Note that

sector,

this average unit-cost

costs introduced

t<T

bClH(t)

>

is

given by

-

exactly equal to the distortion to marginal creation

is

by appropriability. In other words, the appropriability distortion gives an

adequate private signal of the unemployment-cost of creation that appears at the social

level,

side

up

is

to one caveat: the left-hand side" of (28)

is

an average cost, whereas the right-hand

a marginal cost. Because of that subtle difference, private signals do not

full social

reflect the

costs of creation.

To explore

the advisability of a gradualist path of {9(t)},

that maximizes aggregate welfare.

The

we look

first-order condition to the

for the

problem of finding the

optimal path {H°(t)} of creation as driven by the optimal policy {Q°(t)}

c(t)

Compared with the

+ bciH(t) =

f

[6*-

1]

e-^'-^ds,

t

path {9°(t)}

is

< T°.

decentralized free-entry condition (5), the social effective marginal cre-

ation cost exceeds the private cost by a term bc\H{t) which precisely reflects the difference

between marginal and average costs discussed above.

The

fact that the social effective cost of creation

that slowing

down

creation

is

o

beneficial.

e (t)=

i

is

higher than the private one, implies

One can show

that the optimal gradualist path

«*-rk(f-l). 0<t<T°;

1

'

t>T,

e\

24

is

which

clearly less than 9* during the adjustment period.

is