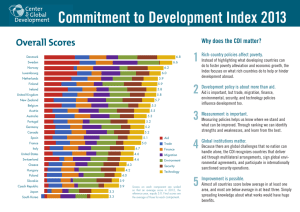

The Commitment to Development Index: 2004 Edition David Roodman

advertisement