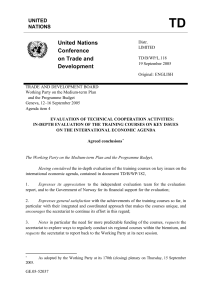

WHO reforms for a healthy future Report by the Director-General INTRODUCTION

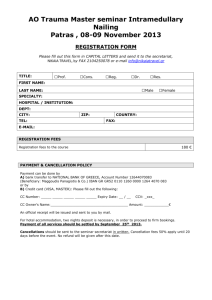

advertisement