ill!

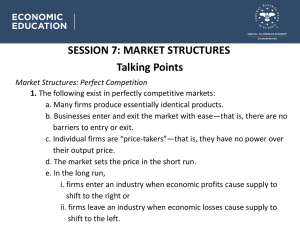

advertisement